Living in Our Watershed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

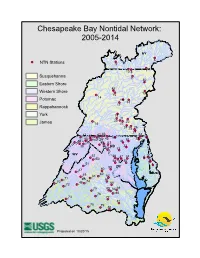

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

Albemarle County Combined Local TMDL Action Plan

Albemarle County Combined Local TMDL Action Plan: Benthic TMDL for the Rivanna River and Bacteria TMDL for the Rivanna River Mainstem, North Fork Rivanna River, Preddy Creek and Tributaries, Meadow Creek, Mechums River, and Beaver Creek Watersheds For Special Condition (Part II.B) of the 2018-2023 VPDES General Permit for Small Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems VAR040074 prepared by: Albemarle County Environmental Services Division 401 McIntire Road Charlottesville, Virginia 22902 (434) 296-5816 www.albemarle.org/water April 30, 2020 Table of Contents List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 1. TMDL Project Name and EPA Approval Dates (Parts II.B.3.a,b) ........................................................... 3 2. Pollutants Causing the Impairments ..................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Benthic TMDL Pollutant ............................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Bacteria TMDL Pollutant ........................................................................................................... 5 3. Wasteload Allocations and Corresponding Percent Reductions (Part II.B.3.c)..................................... 7 3.1 Sediment WLA -

Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority

Rivanna Water & Sewer Authority RESERVOIR WATER QUALITY and MANAGEMENT ASSESSMENT June 2018 Acknowledgements In November 2014, DiNatale Water Consultants and Alex Horne Associates were retained by the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority to develop a comprehensive reservoir water quality monitoring program. This proactive approach is a revision from historic water quality management by the Authority that tended to be more reactive in nature. The Authority embraced the use of sound science in order to develop an approach focused on reservoir management. Baseline data were needed for this scientific approach requiring a labor-intensive, monthly sampling program at all five system reservoirs. Using existing staff resources, the project kicked-off with training sessions on proper sampling techniques and use of sampling equipment. The results and recommendations contained within this report would not have been possible without the capable work of the Rivanna Water and Sewer Authority staff: • Andrea Terry, Water Resources Manager, Reservoir Water Quality and Management Assessment Project Manager • Bethany Houchens, Water Quality Specialist • Bill Mawyer, Executive Director • Lonnie Wood, Director of Finance and Administration • Jennifer Whitaker, Director of Engineering and Maintenance • David Tungate, Director of Operations • Dr. Bill Morris, Laboratory Director • Matt Bussell, Water Manager • Konrad Zeller, Water Treatment Plant Supervisor • Patricia Defibaugh, Lab Chemist • Debra Hoyt, Lab Chemist • Peter Jasiurkowski, Water Operator • Brian -

Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Minerals Of

VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRG INIA 1988 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE. VIRGINIA 1 988 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 89 MINERALS OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY, VIRGINIA Richard S. Mitchell and William F. Giannini COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 19BB DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINERALS AND ENERGY RICHMOND, VIRGIMA O. Gene Dishner, Director COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGIMA DEPARTMENT OF PURCHASES AND SUPPLY RICHMOND Copyright 1988, Commonwealth of Virginia Portions of this publication may be quoted if credit is given to the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources. CONTENTS Page I I I 2 a J A Epidote 5 5 5 Halloysite through 8 9 9 9 Limonite through l0 Magnesite through muscovite l0 ll 1l Paragonite ll 12 l4 l4 Talc through temolite-acti 15 15 l5 Teolite group throug l6 References cited l6 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Location map of I 2. 2 A 4. 6 5. Goethite 6 6. Sawn goethite pseudomorph with unreplaced pyrite center .......... 7 7. 1 8. 8 9. 10. 11. -

Most Effective Basins Funding Allocations Rationale May 18, 2020

Most Effective Basins Funding Allocations Rationale May 18, 2020 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program Office Most Effective Basins Funding In the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Appropriations Conference Report, an increase to the Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP) Budget was provided in the amount of $6 million for “state-based implementation in the most effective basins.” This document describes the methodology EPA followed to establish the most effective use of these funds and the best locations for these practices to be implemented to make the greatest progress toward achieving water quality standards in the Chesapeake Bay. The most effective basins to reduce the effects of excess nutrient loading to the Bay were determined considering two factors: cost effectiveness and load effectiveness. Cost effectiveness was considered as a factor to assure these additional funds result in state-based implementation of practices that achieve the greatest benefit to water quality overall. It was evaluated by looking at what the jurisdictions have reported in their Phase III Watershed Implementation Plans (WIPs) as the focus of their upcoming efforts, and by looking at the average cost per pound of reduction for BMP implementation by sector. Past analyses of cost per pound of reduction have shown that reducing nitrogen is less costly by far than reducing phosphorus1. Based on that fact, EPA determined that the focus of this evaluation would be to target nitrogen reductions in the watershed. Evaluating the load reduction targets in all the jurisdictions’ Phase III WIPs shows that the agricultural sector is targeted for 86 percent of the overall reductions identified to meet the 2025 targets collectively set by the jurisdictions. -

This Annotated Checklist Is Meant to Bring Together Both My Own

28 BANISTERIA NO. 43, 201 4 Walker, J. F., O. K. Miller, Jr., & J. L. Horton. Worley, J. F., & E. Hacskaylo. 1959. The effects of 2008. Seasonal dynamics of ectomycorrhizal fungus available soil moisture on the mycorrhizal association assemblages on oak seedlings in the southeastern of Virginia pine. Forest Science 5: 267-268. Appalachian Mountains. Mycorrhiza 18: 123-132. Yahner, R. H. 2000. Eastern Deciduous Forest Ecology Wilcox, C. S., J. W. Ferguson, G. C. J. Fernandez, & and Wildlife Conservation. University of Minnesota R. S. Nowak. 2004. Fine root growth dynamics of four Press, Minneapolis, MN. 295 pp. Mojave Desert shrubs as related to soil and microsite. Journal of Arid Environments 56: 129-148. Banisteria, Number 43, pages 28-39 © 2014 Virginia Natural History Society Dragonflies and Damselflies of Albemarle County, Virginia (Odonata) James M. Childress 4146 Blufton Mill Road Free Union, Virginia 22940 ABSTRACT The Odonata fauna of Albemarle County, Virginia has been poorly documented, with approximately 20 species on record before this study. My observations from 2006 to 2014, along with historical and other recent records, now bring the total species count for the county to 95. This total includes 64 species of dragonflies, which represents 46% of the 138 species known to occur in Virginia, and 31 species of damselflies, which represents 55% of the 56 species known to occur in Virginia. Also recorded here are the observed date ranges for adults of each species and some observational notes. Key words: Odonata, dragonfly, damselfly, Albemarle County, Virginia. INTRODUCTION STUDY AREA For many counties in Virginia, there has been Albemarle County (Fig. -

Summary of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Suspended-Sediment Loads and Trends Measured at the Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network Stations: Water Year 2016 Update

Summary of Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Suspended-Sediment Loads and Trends Measured at the Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network Stations: Water Year 2016 Update Prepared by Douglas L. Moyer and Joel D. Blomquist, U.S. Geological Survey, December 13, 2017 Changes in nitrogen, phosphorus, and suspended-sediment loads in rivers across the Chesapeake Bay watershed have been calculated using monitoring data from 115 stations that are part of the Non-tidal monitoring network (NTN) (Moyer and others, 2017). Constituent loads are calculated with at least five years of monitoring data and trends are reported after at least ten years of data collection. Data collection began in 1985 at nine of these locations, referred to as River Input Monitoring (RIM) stations, where loads are delivered directly to tidal waters. These results are used to help assess efforts to decrease nutrient and sediment loads being delivered to the bay. Additional information for each monitoring station is available through the USGS Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Web site (https://cbrim.er.usgs.gov/) that provides State, Federal, and local partners, as well as the general public, ready access to a wide range of data for nutrient and sediment conditions across the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Results from two time periods are reported in this summary: a long-term time period (1985- 2016), and short-term time period (2007-2016). All annual results are based on a water year which extends from October 1 to September 30. The results are summarized for 1. loads delivered directly to the tidal waters for the most recent year (Water Year 2016); specifically, the combined load from the nine River Input Monitoring (RIM) stations, 2. -

TMDL) Action Plan for the Rivanna River

City of Charlottesville, Virginia Combined Benthic and Bacteria Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Action Plan for the Rivanna River MS4 General Permit Registration Number VAR040051 July 2016 Table of Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. The name(s) of the Final TMDL report(s) .............................................................................................. 3 2. The pollutant(s) causing the impairment(s) .......................................................................................... 3 3. The WLA(s) assigned to the MS4 as aggregate or individual WLAs ...................................................... 7 4. Significant sources of POC(s) from facilities of concern owned or operated by the MS4 operator that are not covered under a separate VPDES permit. ................................................................................ 8 5. Existing or new management practices, control techniques, and system design and engineering methods , that have been or will be implemented as part of the MS4 Program Plan that are applicable to reducing the pollutant identified in the WLA ................................................................. 9 6. Legal authorities such as ordinances, state and other permits, orders, specific contract language, and interjurisdictional agreements applicable to reducing the POCs identified in each respective TMDL .................................................................................................................................................. -

Albemarle County Biodiversity: a Report on Its History, Current Conditions, and Threats, with Strategies for Future Protection

Albemarle County Biodiversity: A Report on its History, Current Conditions, and Threats, with Strategies for Future Protection Prepared by the Albemarle County Biodiversity Work Group October 2004 Dan Bieker - Ornithologist, Piedmont Virginia Community College Instructor Stephen Bowler, MS – Former Watershed Manager, Albemarle County; Graduate Research Assistant, Virginia Tech Tom Dierauf, Master of Forestry Ruth Douglas, Ph.D. - Invasive Plant Coordinator, Virginia Native Plant Society; Professor Emerita, Piedmont Virginia Community College Michael Erwin, Ph.D. - Research Professor, University of Virginia Department of Environmental Sciences; Wildlife Biologist, USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Chris French – Former Conservation Technician, Thomas Jefferson Soil & Water Conservation District David Hannah, MS – Piedmont Environmental Council (former staff) John Hermsmeier - Director, Environmental Education Center Kenneth R. Lawless, Ph.D. - Professor Emeritus, University of Virginia Department of Materials Science & Engineering; Ornithologist, Field Botanist, Nature Photographer Tom Olivier, Ph.D. - Green Creek Paradigms, LLC G. Carleton Ray, Ph.D. - Research Professor, University of Virginia Department of Environmental Sciences John Scrivani, Ph.D. – Virginia Department of Forestry; Ivy Creek Foundation Board of Directors Charles E. Stevens - Field Botanist and Ornithologist; Virginia Botanical Associates Coordinated and Edited by Scott Clark - Senior Planner, Albemarle County Community Development Department 1 Acknowledgements -

Virginia Scenic Rivers Program

PLANNING AND RECREATION RESOURCES Segments are listed separately if they have a different name, are not connected or are more than five miles. * River is protected with a separate act of the Virginia General Assembly and included with the Scenic Rivers Program. Virginia Scenic Rivers Program Updated July 2021 Designated Reach Total Miles Date Approved Extensions Added River From Downriver To Appomattox River 100 feet from Lake Chesdin Dam James River 19.2 1977 1998, 2011 Banister River Route 29 Bridge Dan River 63.3 2013 2014 Big Cedar Creek Near Lebanon Clinch River 5.8 1992 Blackwater River Proctor's Bridge at Route 621 Nottoway River 56 2010 Catoctin Creek Waterford Potomac River 16 1977 Chickahominy River Route 360 Hanover-Henrico-New Kent county line 10.2 1990 Clinch River Confluence with Indian Creek Russell-Scott county line 66.8 1992 1994, 2020 Cranesnest River Route 637 Flanagan Resevoir Cranesnest Launch Ramp 10.7 2014 Dan River Route 880 at Berry Hill Road Danville's Abreu-Grogan Park 15 2013 Dan River-Halifax N.C. line in Halifax County Aaron's Creek 38.6 2015 Goose Creek North and south prongs of Goose Creek, near Linden Potomac River 48 1976 2007 Grays Creek Route 618 (Southwark Road) James River 6 2020 Guest River 100 feet downstream of Route 72 Clinch River 6.5 1990 Hughes River Shenandoah National Park line Hazel River 10 2010 Historic Falls of the James* West Richmond 1970 city limits Orleans Street (extended) 8.6 1972 1984 Middle James River 1 mile upstream of Warren New Canton 20 2020 Upper James River Confluence of -

2020 Stream Health Report

Photo by Doug RogersDoug by Photo Our Mission Working with the community to conserve the Rivanna River and its tributaries through monitoring, restoration, education, and advocacy. Our Vision We envision a healthy Rivanna River and watershed that benefit an engaged community. 2019 was a successful year for RCA’s Water Quality Monitoring Program. Despite a wet spring and dry fall, we collected samples at all 50 of our long-term biological sites and processed and reported the results of 276 E.coli bacteria samples. We involved 120 volunteers, who graciously contributed 987 hours to our efforts. Our River Stewards also contributed important observational data to the program and we engaged over 900 students from diverse backgrounds in educational monitoring activities. Tracking the long-term “The Rivanna Conservation Alliance was a critical condition of our waterways partner in the development of the North Fork is the foundation of our Rivanna benthic TMDL … RCA staff also played a monitoring work, but it is key role in outreach to engage the local community in benthic data for 19 of the 32 monitoring only one of this program’s the development of the TMDL study …” sites considered in the study. Having such many important a robust dataset helped the group - Nesha McRae, VADEQ Regional TMDL Coordinator contributions. RCA’s develop a more thorough cleanup plan monitoring program also with a strong chance of success. helps improve the health of our waterways and our community. In our watershed, RCA’s monitoring data help The reach of RCA’s monitoring program also extends identify, track, and solve acute water quality problems, like a beyond the Rivanna watershed.