Strategies for Financing Chesapeake Bay Restoration in New York State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45278 SUMMARY R45278 Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and August 3, 2018 Issues for Congress Eva Lipiec The Chesapeake Bay (the Bay) is the largest estuary in the United States. It is Analyst in Natural recognized as a “Wetlands of International Importance” by the Ramsar Convention, a Resources Policy 1971 treaty about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for migratory waterbirds. The Chesapeake Bay estuary resides in a more than 64,000-square-mile watershed that extends across parts of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The Bay’s watershed is home to more than 18 million people and thousands of species of plants and animals. A combination of factors has caused the ecosystem functions and natural habitat of the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed to deteriorate over time. These factors include centuries of land-use changes, increased sediment loads and nutrient pollution, overfishing and overharvesting, the introduction of invasive species, and the spread of toxic contaminants. In response, the Bay has experienced reductions in economically important fisheries, such as oysters and crabs; the loss of habitat, such as underwater vegetation and sea grass; annual dead zones, as nutrient- driven algal blooms die and decompose; and potential impacts to tourism, recreation, and real estate values. Congress began to address ecosystem degradation in the Chesapeake Bay in 1965, when it authorized the first wide-scale study of water resources of the Bay. Since then, federal restoration activities, conducted by multiple agencies, have focused on reducing pollution entering the Chesapeake Bay, restoring habitat, managing fisheries, protecting sub-watersheds within the larger Bay watershed, and fostering public access and stewardship of the Bay. -

New York Buffer Action Plan

Chesapeake Bay Buffer Action Strategy for New York Current Effort Based on the targets set in New York’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan, New York plans to implement 2,606 acres of forest buffer and 1,020 acres of grass buffers in the agriculture sector by 2025. In the urban sector, New York plans to implement 3,095 acres of forest buffer and 1,853 acres of tree planting by 2025. Table 1 shows the current progress in 2020 towards achieving riparian forest buffer targets, the percent achieved, and acres remaining. Table 1 Amount of riparian forest buffer and tree plantings to achieve NY’s WIP III. Best Management Practice 2020 WIP III Percent Acres Acres Progress (acres) Achieved Remaining Needed (acres) per Year Pasture Forest Buffers 2,058 3,543 58% 1,485 297 Pasture Grass Buffers 1,166 1,815 64% 649 130 Cropland Forest Buffers 1,003 2,124 47% 1,121 224 Cropland Grass Buffers 405 776 52% 371 74 Urban Forest Buffers 37 3,132 1% 3,095 619 Opportunities for Implementation Participating Partners New York’s key partners in buffer implementation are the Department of Environmental Conservation, Department of Agriculture and Markets, Upper Susquehanna Coalition, and Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Partners to be further engaged include Farm Service Agency, National Resources Conservation Service, local communities, nongovernment organizations, land trusts and members of the Climate Action Council. Strategy for Implementation As outlined in the Phase III WIP, New York proposes the following strategies to improve its riparian buffer delivery including increase voluntary implementation, explore new funding strategies, sustaining motivation and continuing to support technical capacity. -

Module 1 Overview

Module 1 Educator’s Guide Overview What’s up with Geography Standards World in Spatial Terms Earth’s water • Standard 1: How to use maps and other geographic representations, tools, and technologies to acquire, resources? process, and report information from a spatial perspective Places and Regions Module Overview • Standard 4: The physical and This module addresses issues that are of human characteristics of places fundamental importance to life. Four case Physical Systems studies of a coastal bay, an inland sea, a river, and mountain snow pack • Standard 7: The physical pro- investigate water resources important to millions of people in North cesses that shape the patterns of America, Asia, and Africa. Each investigation focuses on the physical Earth’s surface nature of the resource, how humans depend upon the resource, and how • Standard 8: Characteristics and human use affects the resource creating both problems and opportunities. distribution of ecosystems Environment and Society Investigation 1: Chesapeake Bay: Resource use or abuse? • Standard 14: How humans modify Students play roles of concerned citizens, public officials, and scientists the physical environment • while learning about the Chesapeake Bay and its environs. They use data Standard 15: How physical and satellite images to examine how human actions can degrade, im- systems affect human systems prove, or maintain the quality of the bay in order to make policy recom- The Uses of Geography • Standard 18: How to apply mendations for improving this resource for future use. geography to interpret the present and plan for the future Investigation 2: What is happening to the Aral Sea? Students work as teams of NASA geographers using satellite images to measure the diminishing size of the Aral Sea. -

Environmental Literacy in Delaware

DELAWARE CHESAPEAKE BAY WATERSHED PORTION Environmental Literacy in Delaware Why environmental literacy? How does Delaware compare to the The well-being of the Chesapeake Bay watershed Chesapeake Bay watershed? will soon rest in the hands of its youngest citizens: 2.7 Environmental Literacy Planning: School districts’ self-identified preparedness million students in kindergarten through twelfth grade. to put environmental literacy programs in place Establishing strong environmental education programs Delaware now provides a vital foundation for these future stew- 63% 25% 13% ards. Chesapeake Bay watershed Along with Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and 9% 24% 8% 59% Washington, D.C., Delaware has committed to helping Well-prepared Somewhat prepared its students graduate with the knowledge and skills Not prepared Non-reporting needed to act responsibly to protect and restore their local watersheds. They will do this through: Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences (MWEEs): School districts that reported providing MWEEs to their students • Environmental Literacy Planning: Developing a MWEE Availability in Elementary Schools comprehensive and systemic approach to environ- Delaware mental literacy for students that includes policies, 13% 25% 50% 13% practices and voluntary metrics. Chesapeake Bay watershed • Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences 16% 13% 11% 59% (MWEEs): Continually increasing students’ under- MWEE Availability in Middle Schools standing of the watershed through participation in Delaware teacher-supported Meaningful Watershed Edu- 50% 13% 25% 13% cational Experiences and rigorous, inquiry-based Chesapeake Bay watershed instruction. 18% 14% 9% 59% MWEE Availability in High Schools • Sustainable Schools: Continually increasing the number of schools that reduce the impact of their Delaware buildings and grounds on the environment and 25% 25% 38% 13% human health. -

Land Use Resource Guide

Land Use Resource Guide The Chesapeake Bay Program (CBP), through its Maintain Healthy Watersheds Goal Implementation Team, has a goal of maintaining the long-term health of watersheds identified as healthy by its partner jurisdictions. In addition, under the leadership of the Land Use Workgroup, CBP is working to continually improve our knowledge of land conversion and the associated impacts throughout the watershed. This is a compilation of ongoing initiatives, databases, tools, other resources developed to support local governments and land use managers in designing sustainable landscapes. Land Use Planning Chesapeake Land Use Policy Toolkit: This toolkit provides information about land use policy tools local governments can use to slow the conversion of farmland, forestland, and wetlands from The National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education (NCSG) at the University of Maryland. Accounting for Growth: Factsheet on CBP Land Change Model (CBPLCM) Chesapeake Bay High-Resolution Land Cover: 2013 1-m and 10-m land cover and land use data Chesapeake Phase 6 Land Use Viewer: This data viewer allows you to explore the high-resolution land cover dataset. Chesapeake Bay Watershed Data Dashboard: The Data Dashboard provides information on the economic and community health benefits of pollution reduction and mapped opportunities for land policy, growth management, restoration and conservation practices to help guide watershed planning efforts. EnviroAtlas: Interactive tool from EPA that provides geospatial data, tools, and resources related to ecosystem services, their stressors, and human health to help inform policy and planning decisions. Holistically Analyzing the Benefits of Green Infrastructure: Guidance document for local governments on how to understand and evaluate the benefits of implementing green infrastructure from the Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland. -

Quick Reference Guide for Best Management Practices (Bmps)

1 Prepared by Jeremy Hanson, Virginia Tech/Chesapeake Bay Program CBP/TRS-323-18 Support provided by Virginia Tech, EPA Grant No. CB96326201 Suggested citation: Chesapeake Bay Program. 2018. Chesapeake Bay Program Quick Reference Guide for Best Management Practices (BMPs): Nonpoint Source BMPs to Reduce Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sediment Loads to the Chesapeake Bay and its Local Waters. CBP DOC ID. <link> For individual BMP reference sheets: Chesapeake Bay Program. Title of specific BMP reference sheet. Chesapeake Bay Program Quick Reference Guide for Best Management Practices (BMPs): Nonpoint Source BMPs to Reduce Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sediment Loads to the Chesapeake Bay and its Local Waters, version date of the specific BMP reference sheet. Example: Chesapeake Bay Program. A-3: Conservation Tillage. Chesapeake Bay Program Quick Reference Guide for Best Management Practices (BMPs): Nonpoint Source BMPs to Reduce Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Sediment Loads to the Chesapeake Bay and its Local Waters, MONTH DD, YYYY. 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 About the Chesapeake Bay Program ........................................................................................................ 5 About this Guide ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Understanding Best Management Practices and the Phase -

Stormwater Protection: No Butts About It

Stormwater Protection: No Butts About It Simple truths If you’re reading this, you probably live in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, along with 16 million other people. You may have never set foot in the Bay itself, but your footprint has been carried to its shores nevertheless. The Bay’s shallow aquatic ecosystem, with its peculiar mix of fresh and salt water, is sensitive to changes in water chemistry. Enter the cigarette butt. Cigarette butts accumulate outside buildings, in picnic areas, and along roadsides. These eventually make their way to the Bay via storm drains. According to the organization Clean Virginia Waterways, chemicals leached from a single cigarette butt in a two gallon bucket of Bay water are lethal to aquatic organisms (fish larvae, crustaceans, etc.). Hard Truths On occasion we may view ourselves as external to the Bay’s aquatic ecosystem. It is on those occasions (and when that view is shared by a few million people) that the situation pictured at left is created. Plastics, aluminum cans, cigarette butts, and Styrofoam™ all have one thing in common: buoyancy. According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, stormwater is the fastest growing source of pollution affecting the Bay’s health. This surge in stormwater pollution invariably leads to more junk making its way to the Bay via stormwater. The end result is littered shorelines that compromise the health of underwater vegetation, crabs, oysters, and fish. If you’ve ever sat at a table lined with butcher paper, and uttered the phrase “Save the Crabs/Fish/Oysters So We Can Eat Them” this fact should stir you. -

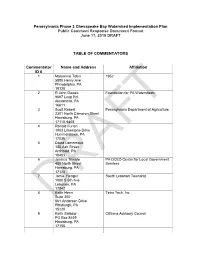

Pennsylvania Phase 3 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Implementation Plan Public Comment Response Document Format June 17, 2019 DRAFT

Pennsylvania Phase 3 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Implementation Plan Public Comment Response Document Format June 17, 2019 DRAFT TABLE OF COMMENTATORS Commentator Name and Address Affiliation ID # 1 Maryanne Tobin 1952 5880 Henry Ave Philadelphia, PA 19128 2 R John Dawes Foundation for PA Watersheds 9697 Loop Rd. Alexandria, PA 16611 3 Scott Rebert Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture 2301 North Cameron Street Harrisburg, PA 17110-9408 4 Ronald Furlan 1903 Limestone Drive Hummelstown, PA 17036 5 David Lamereaux 135 Ash Street Archbald, PA 18403 6 Jessica Trimble PA DCED Center for Local Government 400 North Street Services Harrisburg, PA 17120 7 Jamie Yiengst South Lebanon Township 1800 S 5th Ave Lebanon, PA 17042 8 Keith Henn Tetra Tech, Inc. Suite 200 661 Andersen Drive Pittsburgh, PA 15220 9 Keith Salador Citizens Advisory Council PO Box 8459 Harrisburg, PA 17105 Commentator Name and Address Affiliation ID # 10 Kristopher Troup North Londonderry Township 655 E. Ridge Road Palmyra, PA 17078 11 Cheri Grumbine North Lebanon Township 725 Kimmerlings Road Lebanon, PA 17046 12 Eric Rosenbaum PA4R Nutrient Stewardship Alliance 20 Glenbrook Drive Shillington, PA 19607 13 Jeremy Rowland Coalition for Affordable Bay Solutions 1080 Camp Hill Road (CABS) Fort Washington, PA 19034 14 Joe Pizarchik former director, OSMRE, Dept of the 3000 Berry Lane Interior Harrisburg, PA 17112 15 Mary Gattis Mary Gattis LLC 27 South Cedar Street Lititz, PA 17543 16 Robin Getz Director of Public Works-City of Lebanon Room 220 400 S 8th Street Lebanon, PA 17042 17 Jennifer Reed-Harry PennAg Industries Association 2215 Forest Hills Drive, Suite 39 Harrisburg, PA 17112 18 Kevin Sunday Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and 417 Walnut St Industry Harrisburg, PA 17055 19 Brian Gallagher Western Pennsylvania Conservancy 800 Waterfront Dr. -

What Is the Chesapeake Bay Program and What Does It Offer Me?

What is the Chesapeake Bay Program and what does it offer me? Fueled by science; driven by partnership. Welcome! All participants have been muted. Please use the Q&A function to ask any questions you have! They will be answered in the order they are received after the presentation. This webinar will be recorded. It can be accessed at https://www.chesapeakebay.net/who/group/communications_workgroup by 5:00 p.m. on Thursday, February 25. Having technical issues? Please email [email protected]. What is the Chesapeake Bay Program? A unique regional partnership We are committed to A trusted A partnership. the Chesapeake authority. Bay. What is the Chesapeake Bay Program? ▪ A regional partnership from the federal to the local level working together for an Who is the environmentally and Chesapeake Bay economically sustainable Program? Chesapeake Bay watershed. Who are we not? We are not solely the Environmental Protection Agency. We are not any of the following organizations either. • Chesapeake Bay Foundation • Chesapeake Bay Trust • Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay • Chesapeake Bay Commission • Chesapeake Legal Alliance • Waterkeepers Chesapeake • Chesapeake Research Consortium • Chesapeake Conservancy • Chesapeake Conservation Partnership • Or any others! Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement ▪ Abundant Life ▪ Sustainable Fisheries ▪ Vital Habitats ▪ Clean Water ▪ Healthy Watersheds 5 themes ▪ Toxic Contaminants ▪ Water Quality 10 goals ▪ Climate Change ▪ Climate Resiliency 31 outcomes ▪ Conserved Lands ▪ Land Conservation ▪ Engaged Communities ▪ Environmental Literacy ▪ Public Access ▪ Stewardship https://www.chesapeakebay.net/what/what_guides_us/watershed_agreement Water Quality ▪ Clean Water Goal ▪ 2025 Watershed Implementation Plans ▪ Water Quality Standards Attainment and Monitoring ChesapeakeProgress A publicly-accessible website tracking our progress in meeting the outcomes of the Watershed Agreement. -

Chesapeake Bay Water Quality Modeling Workshop

Chesapeake Bay Water Quality Modeling Workshop August 22, 2019 GODDARD APPLIED SCIENCES NASA Earth Sciences Background and Overview Stephanie Schollaert Uz National Aeronautics and Space Administration Background and Overview • What is the role of NASA Applied Sciences? • Who is the Interagency Chesapeake Bay Working Group? • How have we progressed since last year’s workshop? • What are we doing today and why? NASA uses the vantage point of space to increase our understanding of our home planet, improve lives, and safeguard our future Upcoming NASA missions relevant to water quality? • Plankton Aerosol Cloud ocean Ecosystem (PACE) in Phase C – scheduled to launch in 2022 • Surface Biology and Geology (SBG) study phase – possible launch around 2027 • Geosynchronous Littoral Imaging and Monitoring Radiometer (GLIMR) new venture class award – possible launch around 2025/2027 How do we go from research to operations? Credit: Schollaert Uz, S., G. Kim, G., A. Mannino, et al., In review NASA Applied Sciences bringing the benefits of space back to Earth Managed programs Multidisciplinary areas Health & Water Ecological Food Security & Air Quality Resources Forecasting Agriculture John Haynes Brad Doorn Woody Turner Disasters Capacity Building New Missions International David Green Nancy Searby Collaborations Applied Sciences at Goddard Connecting societal challenges to our basic and applied research to improve life on Earth Water Resources & Food Security Disasters • Identify problems that can be addressed with Earth observations Climate Air -

Cheapeake Bay Program

The Nature Conservancy’s Chesapeake Bay Program Oyster farmers get an early start to the day near the mouth of the Rappahannock River, where it empties into the lower portion of the Chesapeake Bay. © Jason Houston Guided by Science Our Recipe for Success Like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon, our Chesapeake Bay is a national treasure. We bring a global network of experience and knowledge-sharing to But unlike Yellowstone, it is home to 18 million people who depend on the Bay as the bear on Bay conservation strategies. natural engine that powers our region’s economy. Yet in the past two hundred years, we have transformed the ecology of the Bay and much of its six-state watershed, We invest in large-scale, place-based resulting in the severe degradation of the nation’s largest estuary. conservation projects that require sustained funding and management to But science tells us that there is hope. Since the Chesapeake Bay Program was realize success. established in 1983, partners including The Nature Conservancy (TNC), have used We are the largest, non-partisan science to identify priorities, set targets, and track progress toward those goals. NGO working on the Chesapeake Bay The body of scientific knowledge within the Chesapeake Bay watershed is unrivaled, restoration. We deliver policy virtually anywhere else in the world, and TNC is a major contributor to that body of outcomes that no other organization scientific work. As the world’s largest conservation organization, TNC’s work in the Bay can accomplish. watershed helps shape conservation programs around the world. Our staff works on the ground, in local communities across the Bay watershed. -

West Virginia

WEST VIRGINIA Environmental Stewardship in West Virginia What is environmental stewardship? How does West Virginia measure up against To be an environmental steward, residents of the the Chesapeake Bay watershed? Chesapeake Bay watershed can install rain gardens and rain barrels on their properties, avoid using Residents reported tossing litter on fertilizers and pesticides, and take other actions to 4.5% 5.1% the ground when not near a trash can. protect clean water and environmental health. Residents reported flushing Residents can also volunteer in their communities and 8.7% 7.1% engage in civic activities on behalf of the environment. medicines down the drain or toilet. Residents reported using 32.2% 30.2% What is the citizen Stewardship Index? pesticides in or around their homes. The Chesapeake Bay Program surveyed 5,200 Residents reported putting 26.2% 35.6% randomly selected residents of the Chesapeake Bay fertilizers on their grass lawns. watershed portions of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Dog-owners reported seldom or 55.7% 36.1% Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia and the District never picking up their pet's waste. of Columbia about their environmental stewardship actions and attitudes. This group included 600 people from West Virginia, whose answers were used Residents believe their actions to inform the first-ever Chesapeake Bay watershed- 28.2% 35.3% wide Citizen Stewardship Index. contribute to local water pollution. While a perfect Citizen Stewardship score would be possible if everyone in the region were to do Residents want to do more to help make local creeks, 73% 71.2% everything in their daily lives to better the rivers and lakes healthier.