The Glorious American Banner Floating High Above the Ramparts”: the Rise and Fall of Know-Nothingism in Wisconsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War a Thesis Presented to the Department of Humanities

THE KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY: CALLAWAY COUNTY, MISSOURI DURING THE CIVIL WAR A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS By ANDREW M. SAEGER NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI APRIL 2013 Kingdom of Callaway 1 Running Head: KINGDOM OF CALLAWAY The Kingdom of Callaway: Callaway County, Missouri During the Civil War Andrew M. Saeger Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Thesis Advisor Date Dean of Graduate School Date Kingdom of Callaway 2 Abstract During the American Civil War, Callaway County, Missouri had strong sympathies for the Confederate States of America. As a rebellious region, Union forces occupied the county for much of the war, so local secessionists either stayed silent or faced arrest. After a tense, nonviolent interaction between a Federal regiment and a group of armed citizens from Callaway, a story grew about a Kingdom of Callaway. The legend of the Kingdom of Callaway is merely one characteristic of the curious history that makes Callaway County during the Civil War an intriguing study. Kingdom of Callaway 3 Introduction When Missouri chose not to secede from the United States at the beginning of the American Civil War, Callaway County chose its own path. The local Callawegians seceded from the state of Missouri and fashioned themselves into an independent nation they called the Kingdom of Callaway. Or so goes the popular legend. This makes a fascinating story, but Callaway County never seceded and never tried to form a sovereign kingdom. Although it is not as fantastic as some stories, the Civil War experience of Callaway County is a remarkable microcosm in the story of a sharply divided border state. -

Florida Keys Sea Heritage Journal

$2 Florida Keys Sea Heritage Journal VOL. 19 NO. 1 FALL 2008 USS SHARK OFFICIAL QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE KEY WEST MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY The U. S. Navy Wireless Telegraph Stations at Key West and Dry Tortugas By Thomas Neil Knowles (Copyright 2008) On April 24, 1898 the United States declared war on Spain; four months later the fighting had ceased and all that remained to be done was the paperwork. This remarkable efficiency was due in part to both combatants having access to a telegraph system and a global network of overland lines and undersea cables. Even though the battlegrounds were primarily in Cuba and the Philippines, Spain and the United States were able The Naval Station and radio antennas looking west over the houses on Whitehead to coordinate the deployment and Street about WW I. Photo credit: Monroe County Library.. replenishment of their fleets and armies in the Pacific and Atlantic accessible at all to ships at sea. October. Consequently, Marconi theaters direct from Madrid and Several inventors had been and his equipment were still in Washington. working on a wireless telegraph the U. S. when Admiral George The fast-paced conflict system prior to the Spanish- Dewey’s fleet arrived in New York demonstrated the advantages of American War, but it was not from the Philippines. A parade of rapid, worldwide communications until 1899 that the efforts of a 25- ships was organized to honor the for a multitude of purposes year-old Italian showed enough Admiral and his men, and Marconi including the management of promise to attract the interest of was asked to cover the event from fighting forces, news reporting, and the U.S. -

Wisconsin in La Crosse

CONTENTS Wisconsin History Timeline. 3 Preface and Acknowledgments. 4 SPIRIT OF David J. Marcou Birth of the Republican Party . 5 Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus Rebirth of the Democratic Party . 6 Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey WISCONSIN On Wisconsin! . 7 A Historical Photo-Essay Governor James Doyle Wisconsin in the World . 8 of the Badger State 1 David J. Marcou Edited by David J. Marcou We Are Wisconsin . 18 for the American Writers and Photographers Alliance, 2 Professor John Sharpless with Prologue by Former Governor Lee S. Dreyfus, Introduction by Former Governor Patrick J. Lucey, Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage . 26 Foreword by Governor James Doyle, 3 Jim Solberg and Technical Advice by Steve Kiedrowski Portraits and Wisconsin . 36 4 Dale Barclay Athletes, Artists, and Workers. 44 5 Steve Kiedrowski & David J. Marcou Faith in Wisconsin . 54 6 Fr. Bernard McGarty Wisconsinites Who Serve. 62 7 Daniel J. Marcou Communities and Families . 72 8 tamara Horstman-Riphahn & Ronald Roshon, Ph.D. Wisconsin in La Crosse . 80 9 Anita T. Doering Wisconsin in America . 90 10 Roberta Stevens America’s Dairyland. 98 11 Patrick Slattery Health, Education & Philanthropy. 108 12 Kelly Weber Firsts and Bests. 116 13 Nelda Liebig Fests, Fairs, and Fun . 126 14 Terry Rochester Seasons and Metaphors of Life. 134 15 Karen K. List Building Bridges of Destiny . 144 Yvonne Klinkenberg SW book final 1 5/22/05, 4:51 PM Spirit of Wisconsin: A Historical Photo-Essay of the Badger State Copyright © 2005—for entire book: David J. Marcou and Matthew A. Marcou; for individual creations included in/on this book: individual creators. -

November 2020 POLITICAL SHENANIGANS in HISTORIC WISCONSIN

Volume 28 Issue 3 Jackson Historical Society November 2020 POLITICAL SHENANIGANS IN HISTORIC WISCONSIN After Wisconsin became a territory in 1836 and a State in 1848, development continued in earnest. The state had functioned for a num- ber of years with a kind of split personality. The southwest part of the state was industrialized around lead mining, with people arriving up the Mississippi River from the south, seeking their fortune. Cornish immi- grants arrived to work the underground lead mines, giving the state it’s future nickname, Badger. Meanwhile, immigrants arriving in the Wisconsin Territory by ship often settled around the various Lake Michigan ports as that was where Jackson Historical Society Museum commerce was concentrated and many of the jobs were. In the mid 1800’s the state continued to fill up with Yankees, of- ten 2nd generation Americans from the eastern states, immigrants from MEMBERSHIP DUES England, Ireland, and throughout Europe looking to make their way in Your annual $15 dues cover this new state. Land was cheap and opportunities great, with the freedom a calendar year starting in January. to succeed. The current year for your member- Many arriving Yankees were successful or almost successful busi- ship is shown on The Church nessmen looking for another chance to make or increase their fortunes. Mouse address label to the right of Many were speculators, looking for cheap land to buy and resell. Farmers the zip code. and tradesmen arrived with their families looking for inexpensive land and Your dues include a sub- the freedom to establish their farms and businesses. -

Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations George Anastaplo Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected]

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2003 Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations George Anastaplo Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Anastaplo, George, Law, Judges and the Principles of Regimes: Explorations, 70 Tenn. L. Rev. 455 (2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW, JUDGES, AND THE PRINCIPLES OF REGIMES: EXPLORATIONS t GEORGE ANASTAPLO* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................ 456 1. MACHIAVELLI, RELIGION, AND THE RULE OF LAW .............. 459 2. JUDGES, POLITICS, AND THE CONSTITUTION ................... 465 3. A PRIMER ON CONSTITUTIONAL ADJUDICATION ................ 468 4. BILLS OF RIGHTS-ANCIENT, MODERN, AND NATURAL 9. 475 5. THE MASS MEDIA AND THE AMERICAN CHARACTER ............ 481 6. POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY AND A SOFT CAESARISM ............... 491 7. THE PROPER OVERCOMING OF SELF-ASSERTIVENESS ............ 499 8. THE COMMON LAW AND THE JUDICIARY ACT OF 1789 ........... 511 9. A RETURN TO BARRON V. BALTIMORE ........................ 519 10. POLITICAL WILL, THE COMMON GOOD, AND THE CONSTITUTION.. 527 11. TOCQUEVILLE ON THE ROADS TO EQUALITY .................. 532 12. STATESMANSHIP AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW ................ 546 t Law, Judges, and the Principlesof Regimes: Explorations is the first of two articles appearing in the Tennessee Law Review written by Professor Anastaplo. For the second of these two articles, see Constitutionalismandthe Good: Explorations,70 TENN. -

Famous Cases of the Wisconsin Supreme Court

In Re: Booth 3 Wis. 1 (1854) What has become known as the Booth case is actually a series of decisions from the Wisconsin Supreme Court beginning in 1854 and one from the U.S. Supreme Court, Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 514 (1859), leading to a final published decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court in Ableman v. Booth, 11 Wis. 501 (1859). These decisions reflect Wisconsin’s attempted nullification of the federal fugitive slave law, the expansion of the state’s rights movement and Wisconsin’s defiance of federal judicial authority. The Wisconsin Supreme Court in Booth unanimously declared the Fugitive Slave Act (which required northern states to return runaway slaves to their masters) unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned that decision but the Wisconsin Supreme Court refused to file the U.S. Court’s mandate upholding the fugitive slave law. That mandate has never been filed. When the U.S. Constitution was drafted, slavery existed in this country. Article IV, Section 2 provided as follows: No person held to service or labor in one state under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due. Based on this provision, Congress in 1793 passed a law that permitted the owner of any runaway slave to arrest him, take him before a judge of either the federal or state courts and prove by oral testimony or by affidavit that the person arrested owed service to the claimant under the laws of the state from which he had escaped; if the judge found the evidence to be sufficient, the slave owner could bring the fugitive back to the state from which he had escaped. -

2019-2020 Wisconsin Blue Book

Significant events in Wisconsin history First nations 1668 Nicolas Perrot opened fur trade Wisconsin’s original residents were with Wisconsin Indians near Green Bay. Native American hunters who arrived 1672 Father Allouez and Father Louis here about 14,000 years ago. The area’s André built the St. François Xavier mis- first farmers appear to have been the sion at De Pere. Hopewell people, who raised corn, 1673 Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques squash, and pumpkins around 2,000 Marquette traveled the length of the years ago. They were also hunters and Mississippi River. fishers, and their trade routes stretched 1679 to the Atlantic Coast and the Gulf of Daniel Greysolon Sieur du Lhut Mexico. Later arrivals included the (Duluth) explored the western end of Chippewa, Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), Lake Superior. Mohican/Munsee, Menominee, Oneida, 1689 Perrot asserts the sovereignty of Potawatomi, and Sioux. France over various Wisconsin Indian tribes. Under the flag of France 1690 Lead mines are discovered in Wis- The written history of the state began consin and Iowa. with the accounts of French explorers. 1701–38 The Fox Indian Wars occurred. The French explored areas of Wiscon- 1755 Wisconsin Indians, under Charles sin, named places, and established trad- Langlade, helped defeat British Gen- ing posts; however, they were interested eral Braddock during the French and in the fur trade, rather than agricultural Indian War. settlement, and were never present in 1763 large numbers. The Treaty of Paris is signed, mak- ing Wisconsin part of British colonial 1634 Jean Nicolet became the first territory. known European to reach Wisconsin. -

The Truth Behind the Failure of the LIRR's Brooklyn to Boston Route

Did The LIRR's Brooklyn To Boston Route (Ca. 1844- 1847) Fall Victim To Wall Street Stock Manipulation, Unfair Competition From Its “Partner Railroad”, The Untimely Inaction Of Its Own Board, And Finally, A Coup-De-Grace Delivered By The Builder Of The Atlantic Avenue Tunnel- Or Was Its Failure Purely The Result Of Darwinian Market Forces? By Bob Diamond Notes: The very low financial figures cited below need to be put into their proper perspective, in terms of relative value. The total original capitalization of the LIRR, to build from Brooklyn to Greenport (a distance of 95 miles), was, as of the year 1836, $1.5 million. Its construction cost, as estimated by its original Chief Engineer, Maj. D.B. Douglass, was $1.557 million (includes $300,000 to complete the Brooklyn & Jamaica RR). This figure did not include the capital costs of the LIRR's subsequent steamboat operations (New-York Annual Register For The Year 1836, Published by Edwin Williams, 1836, pg 191- 192). The opinions and conclusions cited below are strictly my own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of any other person. Special thanks go to Richard A. Fleischer for his invaluable comments and advice. Back in 1980, in the course of researching the history of the Atlantic Avenue tunnel in order to locate its entrance, I was fascinated to learn the original purpose of the LIRR was to connect New York harbor with Boston and other points in New England, beginning in August 1844, and ending in March, 1847. I was left wondering why this route was abandoned after less than three years of use. -

Seize the Time: the Story of the Black Panther Party

Seize The Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party Bobby Seale FOREWORD GROWING UP: BEFORE THE PARTY Who I am I Meet Huey Huey Breaks with the Cultural Nationalists The Soul Students Advisory Council We Hit the Streets Using the Poverty Program Police-Community Relations HUEY: GETTING THE PARTY GOING The Panther Program Why We Are Not Racists Our First Weapons Red Books for Guns Huey Backs the Pigs Down Badge 206 Huey and the Traffic Light A Gun at Huey's Head THE PARTY GROWS, ELDRIDGE JOINS The Paper Panthers Confrontation at Ramparts Eldridge Joins the Panthers The Death of Denzil Dowell PICKING UP THE GUN Niggers with Guns in the State Capitol Sacramento Jail Bailing Out the Brothers The Black Panther Newspaper Huey Digs Bob Dylan Serving Time at Big Greystone THE SHIT COMES DOWN: "FREE HUEY!" Free Huey! A White Lawyer for a Black Revolutionary Coalitions Stokely Comes to Oakland Breaking Down Our Doors Shoot-out: The Pigs Kill Bobby Hutton Getting on the Ballot Huey Is Tried for Murder Pigs, Puritanism, and Racism Eldridge Is Free! Our Minister of Information Bunchy Carter and Bobby Hutton Charles R. Garry: The Lenin of the Courtroom CHICAGO: KIDNAPPED, CHAINED, TRIED, AND GAGGED Kidnapped To Chicago in Chains Cook County Jail My Constitutional Rights Are Denied Gagged, Shackled, and Bound Yippies, Convicts, and Cops PIGS, PROBLEMS, POLITICS, AND PANTHERS Do-Nothing Terrorists and Other Problems Why They Raid Our Offices Jackanapes, Renegades, and Agents Provocateurs Women and the Black Panther Party "Off the Pig," "Motherfucker," and Other Terms Party Programs - Serving the People SEIZE THE TIME Fuck copyright. -

Appendix C.Vp

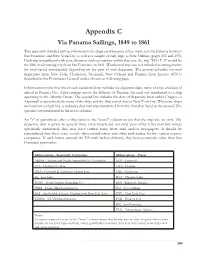

Appendix C Via Panama Sailings, 1849 to 1861 This appendix includes sailing information for ships carrying post office mails sent via Panama between San Francisco and New York City as well as a sample of early trips to New Orleans (pages 252 and 253). Each trip is numbered with year, direction and trip number within that year. So, trip "1851 E-5" would be the fifth mail carrying trip from San Francisco in 1851. Westbound trips are not included as arrangements for mail varied considerably depending on the port of mail departure. The general schedule for mail departures from New York, Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans and Panama from January 1850 is described in the Postmaster General notice shown on following page. Information on the first line of each eastbound trip includes the departure date, name of ship, and date of arrival in Panama City. After carriage across the Isthmus of Panama, the mail was transferred to a ship operating in the Atlantic Ocean. The second line includes the date of departure from either Chagres or Aspinwall as specificed, the name of the ship, and the ship arrival date in New York City. When two ships are listed on a single line, it indicates that mail was transferred from the first ship listed to the second. The specifics are mentioned in the notes column. An "x" in parenthesis after a ship name in the "notes" column means that the trip was an extra. The departure date is given. In general these extra vessels did not carry post office letter mail but, unless specifically mentioned, they may have carried some letter mail and/or newspapers. -

The Crusades Against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate Waves of a Common Current

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 3 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1-1961 The Crusades Against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate Waves of a Common Current Mark W. Cannon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Cannon, Mark W. (1961) "The Crusades Against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate Waves of a Common Current," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol3/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Cannon: The Crusades Against the Masons, Catholics, and Mormons: Separate the crusades against the masons catholics and Morcormonsmormonsmons separate waiveswaves of a common current MARK W CANNON the tradition upsetting election of senator john F kennedy as the first catholic president of the united states provides a remarkable contrast to the crusade against catholics a century ago the theme of this article is that the anti catholic move- ment which reached its zenith in the 1850 s was not unique it reveals common features with the antimasonicanti masonic crusade which flourished in the early 18501830 s and with the anti mormon movement of the 1870 s and 1880 s A comparison of these movements suggests the existence of a subsurface current of american thought which