John Brown's Raid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Annals of Harper's Ferry

WITH =sk@:cs@1m@sM ms m@:m@@z», Many Prominent Characters Cofineciedwiih its History, ' ANECDOTES, &c., \’_ .103)-‘:59 uc\.- 04:3» _' ‘TRRRY Ai" is __1o7 .“BER'Is'_EL‘EYUNION,". m;AR_TmsBURG, W.‘ VA.’ » 0 ~ 1 8‘7 : :§~.ffir3853°3% %~’ JPREFA OE. moi... The unexpected success of a prior and much smaller edition, en courages the author to publish his book on a larger scale than for" merly. It is hoped that it may prove amusing if not very instructive, ~- and the writer feels.confident that, at least, it will give no ofience.— There is “naught set down in malice,”and while the author does not hesitate to avow strong preferences, he has aimed to do so in the mildest manner possible._ On the other hand, fearing lest he may be accused of flattery in some of his sketches, he will take occasion to remark that those who receive his highest encomiums, happen to be the men who deserve the least from him on account of personal favors. He aims do, at least, JUSTICE,toall and, farther, he de sires to say all the good he can of his characters. iiaaas THE ANNAL,sr on HARPER’S 1<”Ja'1eJ.er'., CHAPTER 1. ITS INFANCY. ' tHarper’s Ferry, including Boliver, is a town which, before the re—. bellion, contained a population of three thousand, nine—tenthsofwhom were whites. At the breaking out of the war, nearly all the inhabi _tantsleft their homes, some casting their’lots with “the Confederacy,” and about an equal number with the old Government.’ On the res toration of peace, comparatively few returned. -

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }Udtn-1 M

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }UDtn-1 M. GORDON·OMELKA Great wealth never precluded men from committing themselves to redressing what they considered moral wrongs within American society. Great wealth allowed men the time and money to devote themselves absolutely to their passionate causes. During America's antebellum period, various social and political concerns attracted wealthy men's attentions; for example, temperance advocates, a popular cause during this era, considered alcohol a sin to be abolished. One outrageous evil, southern slavery, tightly concentrated many men's political attentions, both for and against slavery. and produced some intriguing, radical rhetoric and actions; foremost among these reform movements stood abolitionism, possibly one of the greatest reform movements of this era. Among abolitionists, slavery prompted various modes of action, from moderate, to radical, to militant methods. The moderate approach tended to favor gradualism, which assumed the inevitability of society's progress toward the abolition of slavery. Radical abolitionists regarded slavery as an unmitigated evil to be ended unconditionally, immediately, and without any compensation to slaveholders. Preferring direct, political action to publicize slavery's iniquities, radical abolitionists demanded a personal commitment to the movement as a way to effect abolition of slavery. Some militant abolitionists, however, pushed their personal commitment to the extreme. Perceiving politics as a hopelessly ineffective method to end slavery, this fringe group of abolitionists endorsed violence as the only way to eradicate slavery. 1 One abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, a wealthy landowner, lived in Peterboro, New York. As a young man, he inherited from his father hundreds of thousands of acres, and in the 1830s, Smith reportedly earned between $50,000 and $80,000 annually on speculative leasing investments. -

John Brown, Am Now Quite Certain That the Crimes of This Guilty Land Will Never Be Purged Away but with Blood.”

Unit 3: A Nation in Crisis The 9/11 of 1859 By Tony Horwitz December 1, 2009 in NY Times ONE hundred and fifty years ago today, the most successful terrorist in American history was hanged at the edge of this Shenandoah Valley town. Before climbing atop his coffin for the wagon ride to the gallows, he handed a note to one of his jailers: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Eighteen months later, Americans went to war against each other, with soldiers marching into battle singing “John Brown’s Body.” More than 600,000 men died before the sin of slavery was purged. Few if any Americans today would question the justness of John Brown’s cause: the abolition of human bondage. But as the nation prepares to try Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who calls himself the architect of the 9/11 attacks, it may be worth pondering the parallels between John Brown’s raid in 1859 and Al Qaeda’s assault in 2001. Brown was a bearded fundamentalist who believed himself chosen by God to destroy the institution of slavery. He hoped to launch his holy war by seizing the United States armory at Harpers Ferry, Va., and arming blacks for a campaign of liberation. Brown also chose his target for shock value and symbolic impact. The only federal armory in the South, Harpers Ferry was just 60 miles from the capital, where “our president and other leeches,” Brown wrote, did the bidding of slave owners. -

Horatio N. Rust Photograph Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8k35wt7 No online items Horatio N. Rust Photograph Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Suzanne Oatey. Photo Archives The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Horatio N. Rust Photograph photCL 7-11 1 Collection: Finding Aid Descriptive Summary Title: Horatio N. Rust Photograph Collection Dates (inclusive): 1850-1905 Collection Number: photCL 7-11 Creator: Rust, Horatio N. (Horatio Nelson), 1828-1906 Extent: 766 photographs and ephemera in 14 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: A collection of photographs compiled by Horatio N. Rust (1828-1906), U.S. Indian agent and archaeological artifact collector. The main focus of the collection is Indians of Southern California and the Southwest in the late 19th century, including a set of photographs of Southwest Pueblos by John K. Hillers. There is also a collection of photographs related to abolitionist John Brown and his descendants living in the West. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on April 1, 2014. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Boxes 4-7 of photCL 11 contain lantern slides, which are fragile and housed separately from the prints. Advance arrangements for viewing the lantern slides must be made with the Curator of Photographs. -

The Second Raid on Harpers Ferry, July 29, 1899

THE SECOND RAID ON HARPERS FERRY, JULY 29, 1899: THE OTHER BODIES THAT LAY A'MOULDERING IN THEIR GRAVES Gordon L. Iseminger University of North Dakota he first raid on Harpers Ferry, launched by John Brown and twenty-one men on October 16, 1859, ended in failure. The sec- ond raid on Harpers Ferry, a signal success and the subject of this article, was carried out by three men on July 29, 1899.' Many people have heard of the first raid and are aware of its significance in our nation's history. Perhaps as many are familiar with the words and tune of "John Brown's Body," the song that became popular in the North shortly after Brown was hanged in 1859 and that memorialized him as a martyr for the abolitionist cause. Few people have heard about the second raid on Harpers Ferry. Nor do many know why the raid was carried out, and why it, too, reflects significantly on American history. Bordering Virginia, where Harpers Ferry was located, Pennsylvania and Maryland figured in both the first and second raids. The abolitionist movement was strong in Pennsylvania, and Brown had many supporters among its members. Once tend- ing to the Democratic Party because of the democratic nature of PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY: A JOURNAL OF MID-ATLANTIC STUDIES, VOL. 7 1, NO. 2, 2004. Copyright © 2004 The Pennsylvania Historical Association PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY the state's western and immigrant citizens, Pennsylvania slowly gravitated toward the Republican Party as antislavery sentiment became stronger, and the state voted the Lincoln ticket in i 86o. -

Antislavery Violence and Secession, October 1859

ANTISLAVERY VIOLENCE AND SECESSION, OCTOBER 1859 – APRIL 1861 by DAVID JONATHAN WHITE GEORGE C. RABLE, COMMITTEE CHAIR LAWRENCE F. KOHL KARI FREDERICKSON HAROLD SELESKY DIANNE BRAGG A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2017 Copyright David Jonathan White 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the collapse of southern Unionism between October 1859 and April 1861. This study argues that a series of events of violent antislavery and southern perceptions of northern support for them caused white southerners to rethink the value of the Union and their place in it. John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and northern expressions of personal support for Brown brought the Union into question in white southern eyes. White southerners were shocked when Republican governors in northern states acted to protect members of John Brown’s organization from prosecution in Virginia. Southern states invested large sums of money in their militia forces, and explored laws to control potentially dangerous populations such as northern travelling salesmen, whites “tampering” with slaves, and free African-Americans. Many Republicans endorsed a book by Hinton Rowan Helper which southerners believed encouraged antislavery violence and a Senate committee investigated whether an antislavery conspiracy had existed before Harpers Ferry. In the summer of 1860, a series of unexplained fires in Texas exacerbated white southern fear. As the presidential election approached in 1860, white southerners hoped for northern voters to repudiate the Republicans. When northern voters did not, white southerners generally rejected the Union. -

WVRHC Newsletter, Spring 2009 West Virginia & Regional History Center

West Virginia & Regional History Center University Libraries Newsletters Spring 2009 WVRHC Newsletter, Spring 2009 West Virginia & Regional History Center Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvrhc-newsletters Part of the History Commons West Virginia and egional History Collection NEWSLETTER Volume 24, No. 2 West Virginia University Libraries Spring 2009 The John Brown Raid "Notes by an Eyewitness" Preserved in the Regional History Collection On the morning of the 17th of October 1859 I was engaged in my office at Martinsburg when I was informed that there was an insurrection of some sort at Harpers ferry and that the night train for Passengers and the morning Freight trains on the Baltimore & Ohio R. Road had Storming of the Engine House at Harpersferry Capture of John Brown October 1859 been stopped and turned back.... With the above words, David Hunter Strother {1816-1888) commenced a personal he have extraordinary literary prowess but also journal entry describing one of the most poignant possessed artistic talents that made him one of episodes in American history -John Brown's raid the finest illustrators of his day. In addition, he on Harpers Ferry. enjoyed yet another singular advantage - the trust Nationally known by his pen name, and cooperation of the local authorities who Porte Crayon, the most popular contributor to captured, tried and eventually hung the great America's favorite periodical, Harpers Monthly, anti-slavery crusader. The judge who presided over Strother was well qualified to document the Brown's trial was a close family friend. The historic events that unfolded one hundred and prosecutor, Andrew Hunter, was Strother's uncle. -

John Brown's Raid: Park Videopack for Home and Classroom. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 957 SO 031 281 TITLE John Brown's Raid: Park VideoPack for Home and Classroom. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-912627-38-7 PUB DATE 1991-00-00 NOTE 114p.; Accompanying video not available from EDRS. AVAILABLE FROM Harpers Ferry Historical Association, Inc., P.O. Box 197, Harpers Ferry, WV 25425 ($24.95). Tel: 304-535-6881. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom - Teacher (052)-- Historical Materials (060)-- Non-Print Media (100) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); Curriculum Enrichment; Heritage Education; Historic Sites; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; *Slavery; Social Studies; Thematic Approach; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Brown (John); United States (South); West Virginia; *West Virginia (Harpers Ferry) ABSTRACT This video pack is intended for parents, teachers, librarians, students, and travelers interested in learning about national parklands and how they relate to the nation's natural and cultural heritage. The video pack includes a VHS video cassette on Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, an illustrated handbook with historical information on Harpers Ferry, and a study guide linking these materials. The video in this pack, "To Do Battle in the Land," documents John Brown's 1859 attempt to end slavery in the South by attacking the United States Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). The 27-minute video sets the scene for the raid that intensified national debate over the slavery issue. The accompanying handbook, "John Brown's Raid," gives a detailed account of the insurrection and subsequent trial that electrified the nation and brought it closer to civil war. -

John Brown, Abolitionist: the Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S

John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights by David S. Reynolds Homegrown Terrorist A Review by Sean Wilentz New Republic Online, 10/27/05 John Brown was a violent charismatic anti-slavery terrorist and traitor, capable of cruelty to his family as well as to his foes. Every one of his murderous ventures failed to achieve its larger goals. His most famous exploit, the attack on Harpers Ferry in October 1859, actually backfired. That backfiring, and not Brown's assault or his later apotheosis by certain abolitionists and Transcendentalists, contributed something, ironically, to the hastening of southern secession and the Civil War. In a topsy-turvy way, Brown may have advanced the anti-slavery cause. Otherwise, he actually damaged the mainstream campaign against slavery, which by the late 1850s was a serious mass political movement contending for national power, and not, as Brown and some of his radical friends saw it, a fraud even more dangerous to the cause of liberty than the slaveholders. This accounting runs against the grain of the usual historical assessments, and also against the grain of David S. Reynolds's "cultural biography" of Brown. The interpretations fall, roughly, into two camps. They agree only about the man's unique importance. Writers hostile to Brown describe him as not merely fanatical but insane, the craziest of all the crazy abolitionists whose agitation drove the country mad and caused the catastrophic, fratricidal, and unnecessary war. Brown's admirers describe his hatred of slavery as a singular sign of sanity in a nation awash in the mental pathologies of racism and bondage. -

Harpers Ferry and the Story of John Brown

Harpers Ferry and the Story of John Brown STUDY GUIDE Where History and Geography Meet Today, John Brown's war against slavery can be seen as a deep, divisive influence on the course of mid-19th century American politics. This Study Guide, along with the book John Brown's Raid and the video To Do Battle in This Land, is designed to help junior and senior high school teachers prepare their students to understand this essential issue in American history. It can also be used to lay the groundwork for a visit to Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, where travelers can explore firsthand the places associated with the event that intensified national debate over the slavery issue and helped to bring on the Civil War. Harpers Ferry and the Story of John Brown STUDY GUIDE Produced by the Division of Publications, National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., 1991 Contents Introduction The Study Guide and How to Use It 4 Using the Book and Video Synopsis 6 Pre-viewing Discussion Questions and Activities 7 Post-viewing Discussion Questions and Activities 8 Extended Lessons Law, Politics, Government, and Religion 10 The Importance of Geography 12 Slavery and the Constitution 13 Property and Economics 14 The Role of the Media 15 Women's Rights 16 Literature 17 Music 18 Resources Glossary 19 Chronology of John Brown's Life and Related Events 20 Chronology of John Brown's Raid on Harpers Ferry, 1859 22 Harpers Ferry and Vicinity in 1859 24 Harpers Ferry in 1859 25 U.S. -

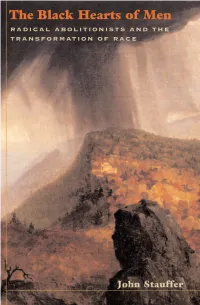

Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race

the black hearts of men John Stauffer The Black Hearts of Men radical abolitionists and the transformation of race harvard university press cambridge, massachusetts and london, england Copyright © 2001 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2004 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stauffer, John. The black hearts of men : radical abolitionists and the transforma- tion of race / John Stauffer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-674-00645-3 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-01367-0 (pbk.) 1. Abolitionists—United States—History—19th century. 2. Antislavery movements—United States—History—19th century. 3. Abolitionists—United States—Biography. 4. Smith, James McCune, 1813–1865. 5. Smith, Gerrit, 1797–1874. 6. Douglass, Frederick, 1817?–1895. 7. Brown, John, 1800–1859. 8. Radical- ism—United States—History—19th century. 9. Racism—United States—Psychological aspects—History—19th century. 10. United States—Race relations—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. E449 .S813 2001 973.7Ј114Ј0922—dc21 2001039474 For David Brion Davis Contents A Introduction • 1 one The Radical Abolitionist Call to Arms • 8 two Creating an Image in Black • 45 three Glimpsing God’s World on Earth • 71 four The Panic and the Making of Abolitionists • 95 five Bible Politics and the Creation of the Alliance • 134 six Learning from Indians • 182 seven Man Is Woman and Woman Is Man • 208 eight The Alliance Ends and the War Begins • 236 Epilogue • 282 Abbreviations · 287 Notes · 289 Acknowledgments · 355 Index · 359 the black hearts of men Introductionthe black hearts of men Introduction A The white man’s unadmitted—and apparently, to him, unspeakable— private fears and longings are projected onto the Negro. -

Bleeding Kansas Series Returns to Constitution Hall State Historic Site

December 30, 2014 Bleeding Kansas Series Returns to Constitution Hall State Historic Site LECOMPTON, KS—Dramatic interpretations and talks about the violent conflict over slavery highlight the 19th annual Bleeding Kansas series, which begins January 25, 2015. The programs are held at 2 p.m. Sundays, through March 1. Bleeding Kansas describes that time in Kansas Territory, from 1854 to 1861, during the struggle to determine whether the new state would be free or slave. Each of these programs explores aspects of the state’s unique history. January 25 - “The Kansas Statehouse Restoration,” Barry Greis, statehouse architect, with remarks by Matt Veatch, state archivist, Kansas Historical Society. This program is a Kansas Day commemoration. February 1 - “Railroad Empire Across the Heartland: Rephotographing Alexander Gardner's 1867 Westward Journey Through Kansas,” John Charlton, photographer, Kansas Geological Survey, University of Kansas with remarks by Nancy Sherbert, curator of photographs, Kansas Historical Society. Charlton will sign copies of his book after the presentation, which will be available for purchase the day of the event. February 8 - “John Brown vs. W.B. 'Ft. Scott' Brockett,” first-person portrayals by Kerry Altenbernd, as abolitionist John Brown, and Jeff Quigley, as proslavery advocate W.B. Brockett, discussing Bleeding Kansas and the Battle of Black Jack. February 15 - “James Montgomery, The Original Jayhawker,” Max Nehrbass, Labette Community College history instructor, with historian Rich Ankerholz portraying James Montgomery. February 22 - "If It Looks Like a Man: Female Soldiers and Lady Bushwhackers in the Civil War in Kansas and Missouri," Diane Eickhoff and Aaron Barnhart, authors and historians. March 1 - “John Brown’s Money Man: George Luther Stearns, Abolitionist,” Dr.