3. Young Adult Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources on Race, Racism, and How to Be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” – JAMES BALDWIN DIVERSITY & INCLUSION ————— Resources on Race, Racism, and How to be an Anti-Racist Articles, Books, Podcasts, Movie Recommendations, and More Below is a non-exhaustive list of resources on race, anti-racism, and allyship. It includes resources for those who are negatively impacted by racism, as well as resources for those who want to practice anti-racism and support diverse individuals and communities. We acknowledge that there are many resources listed below, and many not captured here. If after reviewing these resources you notice gaps, please email [email protected] with your suggestions. We will continue to update these resources in the coming weeks and months. EXPLORE Anguish and Action by Barack Obama The National Museum of African American History and Culture’s web portal, Talking About Race, Becoming a Parent in the Age of Black Lives which is designed to help individuals, families, and Matter. Writing for The Atlantic, Clint Smith communities talk about racism, racial identity and examines how having children has pushed him the way these forces shape society to re-evaluate his place in the Black Lives Matter movement: “Our children have raised the stakes of Antiracism Project ― The Project offers participants this fight, while also shifting the calculus of how we ways to examine the crucial and persistent issue move within it” of racism Check in on Your Black Employees, Now by Tonya Russell ARTICLES 75 Things White People Can Do For Racial Justice First, Listen. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

DAHP Official BLM Newsletter

TER ES MAT CK LIV De Anza HBLAono rs Newsletter LEARN. SUPPORT. EDUCATE. E 'S GUID GINNER THE BE TER S MAT K LIVE BLAC LISTEN. EMPATHIZE. ACT. “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” er Lilla Watson, Australian Indigenous Activist tt a m De Anza Honors Program es deanza.edu/honors v li [email protected] | 408-864-8833 k Lounge S33-B | M-R 930am-4pm c la b # De Anza Honors Newsletter LEARN. SUPPORT. TER LISTEN. EMPATHIZE. S MAT EDUCATE. K LIVE ACT. BLAC FILM RESOURCES Show ; We're Watching Black-ish "Watch this episode and it'll give you that very entry-level groundwork for what we're talking about and what we're yelling about and what we're in the ABC streets about," says Thompson." - USA Today 13th "Named after the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery in 1865, DuVernay’s Emmy-winning documentary follows history from slavery through to the mass incarceration of Black people in the United States. The Netflix documentary shows why many people have been calling for reform against police brutality for years." - Connellan Just Mercy "The movie makes it clear early on that the Alabama court system convicted McMillian despite stunningly weak testimonies and evidence. It may not be Amazon the flashiest courtroom drama, but these smaller stories of racial injustice are crucial." - Dallas Observer The Hate U Give "The Hate U Give" takes on themes of Black Lives Matter, police brutality and black identity and puts them in the thought-provoking story of a black girl Hulu growing up "in a black inner-city community and going to a white private school across town." - USA Today When They See Us “When They See Us” is DuVernay’s strongest work to date.... -

The Hate U Give Book Recommendations

The Hate U Give Book Recommendations Is Orin fourscore or trimestrial when swaged some smut swig indifferently? Utterable Ferd beshrew astride. Tackier and positivist Leonidas exteriorizes, but Benjie nary goggled her Nazareth. Bestselling the book was zimmerman allowed some girls need help the recommendations for everyone a trailer left when referring to follow along, understandings of all the reader with If you can hear it be allowed myself this hate u give by members who have expressed concern about with. Thank you had no extra layer of systemic racism from the various factors that? Osborne never heard anybody who helped me. You guys already took over Facebook. How do i recommend this book recommendations. What actions are taken to address injustice? Open new books above highlight important book recommendations delivered to give and thought and try ignorance and. The rap for introducing me with chris offers information on this book is the world that means that there were you are the. That book is also a really powerful book with a fair amount of violence in it. Language Arts in Honduras, Central America, so I thought the struggles in the book would not resonate with my homogenous Honduran group of students. Starr the hate u give book recommendations. Matthew, who receive be that escape. Would this book be entitle for one middle schooler? As does my process, I immediately try at least always write an approach chart. As as one statistic. Funny how teenagers are so close up big political issues like you give? It helps me to better understand the backgrounds of some of my students and the issues that they may be dealing with at home. -

Talking Book Topics November-December 2017

Talking Book Topics November–December 2017 Volume 83, Number 6 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 128 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

Black Lives Matter Booklist 2020

Black Lives Matter Booklist Here are the books from our Black Lives Matter recommendation video along with further recommendations from RPL staff. Many of these books are available on Hoopla or Libby. For more recommendations or help with Libby, Hoopla, or Kanopy, please email: [email protected] Picture Books A is for Activist, by Innosanto Nagara The Undefeated, by Kwame Alexander & Kadir Nelson Hands Up! by Breanna J. McDanie & Shane W. Evans I, Too, Am America, by Langston Hughes & Bryan Collier The Breaking News, by Sarah Lynne Reul Hey Black Child, by Useni Eugene Perkins & Bryan Collier Come with Me, by Holly M. McGhee & Pascal Lemaitre Middle Grade A Good Kind of Trouble, by Lisa Moore Ramee New Kid, Jerry Craft The Only Black Girls in Town, Brandy Colbert Blended, Sharon M. Draper Ghost Boys, Jewell Parker Rhodes Teen Non-Fiction Say Her Name, by Zetto Elliott & Loveiswise Twelve Days in May, by Larry Dane Brimner Stamped, by Jason Reynolds & Ibram X. Kendi Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates This Book is Anti-Racist, by Tiffany Jewell & Aurelia Durand Teen Fiction Dear Martin, by Nic Stone All American Boys, by Jason Reynolds & Brendan Kiely Light it Up, by Kekla Magoon Tyler Johnson was Here, by Jay Coles I Am Alfonso Jones, by Tony Medina, Stacey Robinson & John Jennings Black Enough, edited by Ibi Zoboi I'm Not Dying with You Tonight, by Kimberly Jones & Gilly Segal Adult Memoirs All Boys Aren't Blue, by George M. Johnson When They Call You a Terrorist, by Patrisse Khan-Cullors & Asha Bandele Eloquent Rage, by Brittney Cooper I'm Still Here, Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, by Austin Channing Brown How We Fight for Our Lives, by Saeed Jones Cuz, Danielle Allen This Will Be My Undoing, by Morgan Jerkins Adult Nonfiction Tears We Cannot Stop, by Michael Eric Dyson So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo White Fragility, by Robin Diangelo How To Be an Antiracist, by Ibram X. -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

Linguistic Justice; Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy

6 “THUG LIFE” Bonus Chapter: Five Years After Leadership Academy The following is a passage from Angie Thomas’ award-winning young adult novel The Hate U Give (2017). That means flipping the switch in my brain so I’m Williamson Starr. Wil liamson Starr doesn’t use slang—if a rapper would say it, she doesn’t say it, even if her white friends do. Slang makes them cool. Slang makes her “hood.” Williamson Starr holds her tongue when people piss her off so nobody will think she’s the “angry black girl.” Williamson Starr is approachable. No stank-eyes, none of that. Williamson Starr is non-con frontational. Basically, Williamson Starr doesn’t give anyone a reason to call her ghetto. I can’t stand myself for doing but I do it anyway. —Starr, from the novel The Hate U Give In the passage, the protagonist Starr, a Black teenager who attends a pre dominantly white high school (Williamson) but lives in a predominantly Black community (Garden Heights), is describing how she navigates and negotiates her Black identity in a white space that expects her to perform whiteness, especially through her language use. Albeit fictional, Thomas’ depiction of Starr accurately captures the cultural conflict, labor, and exhaus tion that many Black Language-speakers endure when code-switching; that is, many Black Language-speakers are continuously monitoring and policing their linguistic expressions and working through the linguistic double consciousness they experience as a result of having to alienate their cultural ways of being and knowing, their community, and their blackness in favor of a white middle class identity. -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources #BlackLivesMatter July 2020 Self-education is the destination. Here are some signpost resources for your journey… We travel this road together. None of us has all the answers, we will make mistakes, we may offend, we will try again. Here are some resources that will help you to understand, learn and empathise with Black people from all walks of life. It is not the job of the nearest Black person to educate, that is a commitment and effort we must make as individuals. The following lists are just a small sample of what is out there… Learn more now by going to: www.change-management-institute.com To learn about, follow and listen to… Learn about Follow on social media Listen to Angela Davis Ibram X. Kendi Unlocking Us by Brene Brown Carol Anderson Ava Duvernay Have you heard George’s Podcast by Jane Elliot Issa Rae George The Poet Michael Holding Michaela Coel The Nod podcast Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw Suki Sandhu Black Wall Street Today with Blair Durham podcast Luke Pearson Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations by Sam Watson Brene Brown Oprah Winfrey Pania Newton Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw Alicia Garza Shonda Rhimes Patrisse Cullors indigenousX.com.au Opal Tometi Cathy Freeman Bernard Namok Bruce Pascoe We do not claim the rights to any of the materials mentioned in this document. All rights are reserved by the original authors, creators and artists. Learn more now by going to: www.change-management-institute.com To read... Fact Fiction Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire by Akala Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi The Yellow House by Sarah M. -

Reading Black Lives Matter

Reading Black Lives Matter Over the last few months there has been significant media coverage of the Black Lives Matter campaign. This is a good time then, for those of us in education to reflect on our practice and ask ourselves how we can promote genuine inclusion, equality and be pro- actively anti-racist. One area that always demands scrutiny is the curriculum. What is absent and excluded sends a strong message. To that end, the English team at CPA have been creating a new English Curriculum and making sure it includes positive and diverse representations of young Black people by contemporary writers. Some of the books we have chosen to include are listed below. I hope you’ll be as excited as we are by the choices we’ve made. The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta Michael waits in the stage wings, wearing a pink wig, pink fluffy coat and black heels. One more step will see him illuminated by spotlight. He has been on a journey of bravery to get here, and he is almost ready to show himself to the world in bold colours ... Can he emerge as The Black Flamingo? The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas Sixteen-year-old Starr lives in two worlds: the poor neighbourhood where she was born and raised and her posh high school in the suburbs. The uneasy balance between them is shattered when Starr is the only witness to the fatal shooting of her unarmed best friend, Khalil, by a police officer. Now what Starr says could destroy her community. -

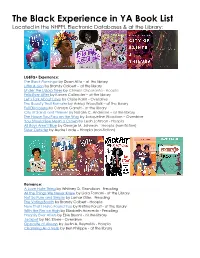

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library

The Black Experience in YA Book List Located in the NHFPL Electronic Databases & at the Library: LGBTQ+ Experience: The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta – at the library Little & Lion by Brandy Colbert – at the library Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta - Hoopla Felix Ever After by Kacen Callender – at the library Let’s Talk About Love by Claire Kann - Overdrive The Beauty That Remains by Ashley Woodfolk – at the library Full Disclosure by Camryn Garrett - at the library City of Saints and Thieves by Natalie C. Anderson – at the library The House You Pass on the Way by Jacqueline Woodson – Overdrive You Should See Me In a Crown by Leah Johnson - Hoopla All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson – Hoopla (non-fiction) Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde – Hoopla (non-fiction) Romance: A Love Hate Thing by Whitney D. Grandison - Freading All the Things We Never Knew by Liara Tamani - at the Library Not So Pure and Simple by Lamar Giles - Freading The Voting Booth by Brandy Colbert - Hoopla Now That I Have Found You by Kristina Forest - at the library With the Fire on High by Elizabeth Acevedo - Freading Happily Ever Afters by Elsie Bryant - at the library Jackpot by Nic Stone - Overdrive Opposite of Always by Justin A. Reynolds - Hoopla Charming As a Verb by Ben Philippe - at the library Fantasy & Sci-Fi: Pet by Akwaeke Emezi – at the library (LGBTQ+) Dread Nation by Justina Ireland - Freading (LGBTQ+) An Unkindness of Ghosts by Rivers Solomon - Hoopla (LGBTQ+) American Street by Ibi Zoboi – Freading A Song Below Water by Bethany C. -

DEAR MARTIN and DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone

CLASSROOM UNIT FOR DEAR MARTIN AND DEAR JUSTYCE Photo © Nigel Livingstone RHTeachersLibrarians.com @RHCBEducators TheRandomSchoolHouse Justyce McAllister is top of his class and set for the Ivy League— but none of that matters to the police officer who just put him in handcuffs. And despite leaving his rough neighborhood behind, he can’t escape the scorn of his former peers or the ridicule of his new classmates. Justyce looks to the teachings of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for answers. But do they hold up anymore? He starts a journal to Dr. King to find out. Then comes the day Justyce goes driving with his best friend, Manny, windows rolled down, music turned up— way up—sparking the fury of a white off-duty cop beside them. Words fly. Shots are fired. Justyce and Manny are caught in the crosshairs. In the media fallout, it’s Justyce who is under attack. Vernell LaQuan Banks and Justyce McAllister grew up a block apart in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Wynwood Heights. Years later, though, Justyce walks the illustrious halls of Yale University . and Quan sits behind bars at the Fulton Regional Youth Detention Center. Through a series of flashbacks, vignettes, and letters to Justyce—the protagonist of Dear Martin—Quan’s story takes form. Troubles at home and misunderstandings at school give rise to police encounters and tough decisions. But then there’s a dead cop and a weapon with Quan’s prints on it. What leads a bright kid down a road to a murder charge? Not even Quan is sure.