Death and Resurrection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

Parte Seconda Bibliotheca Collinsiana, Seu Catalogus Librorum Antonji Collins Armigeri Ordine Alphabetico Digestus

Parte seconda Bibliotheca Collinsiana, seu Catalogus Librorum Antonji Collins Armigeri ordine alphabetico digestus Avvertenza La biblioteca non è solo il luogo della tua memoria, dove conservi quel che hai letto, ma il luogo della memoria universale, dove un giorno, nel momento fata- le, potrai trovare quello che altri hanno letto prima di te. Umberto Eco, La memoria vegetale e altri scritti di bibliografia, Milano, Rovello, 2006 Si propone qui un’edizione del catalogo manoscritto della collezione libra- ria di Anthony Collins,1 la cui prima compilazione egli completò nel 1720.2 Nei nove anni successivi tuttavia Collins ampliò enormemente la sua biblioteca, sin quasi a raddoppiarne il numero delle opere. Annotò i nuovi titoli sulle pagine pari del suo catalogo che aveva accortamente riservato a successive integrazio- ni. Dispose le nuove inserzioni in corrispondenza degli autori già schedati, attento a preservare il più possibile l’ordine alfabetico. Questo tuttavia è talora impreciso e discontinuo.3 Le inesattezze, che ricorrono più frequentemente fra i titoli di inclusione più tarda, devono imputarsi alla difficoltà crescente di annotare nel giusto ordine le ingenti e continue acquisizioni. Sono altresì rico- noscibili abrasioni e cancellature ed in alcuni casi, forse per esigenze di spazio, oppure per sostituire i titoli espunti, i lemmi della prima stesura sono frammez- zati da titoli pubblicati in date successive al 1720.4 In appendice al catalogo, due liste confuse di titoli, per la più parte anonimi, si svolgono l’una nelle pagi- ne dispari e l’altra in quelle pari del volume.5 Agli anonimi seguono sparsi altri 1 Sono molto grato a Francesca Gallori e Barbara Maria Graf per aver contribuito alla revi- sione della mia trascrizione con dedizione e generosità. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Checklist of Thomas Hollis's Gifts to the Harvard College Library.Pdf

Checklist of Thomas Hollis’s gifts to the Harvard College Library The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bond, William H. 2010. Checklist of Thomas Hollis’s gifts to the Harvard College Library. Harvard Library Bulletin 19 (1-2), Spring/ Summer 2008: 34-205. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42669145 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Figure 3. Bibliotheca Literaria (London, 1722-1724). On the front fyleaf of a book given in 1767, TH provides a modest overview of his gifs on diferent subjects. See Introduction, pp. 22-23, and Checklist, p. 49. *EC75.H7267.Zz722b 23 cm. Checklist of Tomas Hollis’s Gifs to the Harvard College Library A Abbati Olivieri-Giordani, Annibale degli, 1708-1789. Marmora Pisaurensia (Pesaro, 1738). Inv.4.2; 2.3.2.12; C7 <641212?, h> f *IC7.Ab196.738m Abela, Giovanfrancesco, 1582-1655. ‡Della descrittione di Malta . libri quattro (Malta, 1647). 4.3.4.18; C48 <nd, v> On fyleaf: “Te ever-warring, lounging Maltese!” On half title: “Libro raro T·H.” f *EC75.H7267.Zz647a Abu al-Faraj, see Bar Hebraeus, Specimen historiae Arabum Académie des jeux floraux (France). Receuil de plusieurs pièces d’éloquence (Toulouse, [n.d.]). Inv.4.110; 2.2.7.15; not in C <641212?> Original Hollis gif not located. -

Unit 2 BRITISH LITERATURE LIFEPAC 2 the SIXTEENTH CENTURY

Unit 2 BRITISH LITERATURE LIFEPAC 2 THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY CONTENTS I. THE RENAISSANCE AND REFORMATION • • • • • • • • • 1 INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 THE EARLY RENAISSANCE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 11 Sir Thomas More • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 11 Roger Ascham • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 18 John Foxe • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 23 II. RENAISSANCE POETS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 41 Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 41 Sir Philip Sydney • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 43 Edmund Spenser • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 51 Mary (Sydney) Herbert, Countess of Pembroke • • • • 60 III. RENAISSANCE PROSE AND DRAMA • • • • • • • • • • • • 67 Sir Walter Raleigh • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 67 William Shakespeare • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 71 The English Bible • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 110 Author: Krista L. White, B.S. Editor: Alan Christopherson, M.S. Graphic Design: Alpha Omega Graphics 804 N. 2nd Ave. E., Rock Rapids, IA 51246-1759 © MM by Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. LIFEPAC is a registered trademark of Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All trademarks and/or service marks referenced in this material are the property of their respective owners. Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. makes no claim of ownership to any trademarks and/or service marks other than their -

Services and Music for October 2017

Services and Music for October 2017 16 MONDAY 20 FRIDAY 23 MONDAY 27 FRIDAY Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London, and Hugh Latimer, no specials today no specials today no specials today Bishop of Worcester, Reformation Martyrs, 1555 8.30 Morning Prayer Christ in Gethsemane 8.30 Morning Prayer & Holy Communion Lady Chapel 8.30 Morning Prayer Christ in Gethsemane 8.30 Morning Prayer & Holy Communion Lady Chapel 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Ruins 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Ruins 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 12.10 Holy Communion Chapel of Unity 5.15 Evening Prayer West End 12.10 Holy Communion Chapel of Unity 5.15 Choral Evensong (Whitgift School) Chancel 5.15 Evening Prayer Christ in Gethsemane 5.15 Evening Prayer Christ in Gethsemane Radcliffe Responses Psalm 85 Kelly Canticles in C Ireland Greater love 17 TUESDAY 21 SATURDAY 24 TUESDAY 28 SATURDAY Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, Martyr, c.107 no specials today no specials today Simon and Jude, Apostles 8.30 Morning Prayer Christ in Gethsemane 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 8.30 Morning Prayer Christ in Gethsemane 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 12.10 Holy Communion Chapel of Unity 12.00 Litany of Reconciliation Nave 12.10 Holy Communion Chapel of Unity 1.00 Holy Communion Holy Trinity 4.00 Choral Evensong (Christ Church Cathedral Singers)Chancel 1.00 Holy Communion Holy Trinity 4.00 Choral Evensong (Beverley Minster) Chancel and Prayers for Healing Shephard A new commandment and Prayers for Healing Stanford Beati quorum via 1.05 Ecumenical Service Chapel of Unity Ives, G. -

STORY of ANGLICANISM

STORY of ANGLICANISM PART 1 (26th May 2018) ANCIENT & MEDIEVAL FOUNDATIONS When does Anglican history begin? The 16th century division of medieval Christendom into national and denominational jurisdictions marked the beginning of separate development in English religion. But to understand the particular shape of Anglicanism, it is helpful to know the pre-Reformation church from which it evolved. Our study of the ancient and medieval English Church will not only illumine generic topics of Christian history (eg. conversion of the barbarians, the monastic ideal the struggles of bishops and kings, etc.), but it will also reveal certain Anglican traits rooted deeply in the past of Britain’s relatively pragmatic and moderate peoples. This is perhaps a point not to be pressed too far, lest the increasingly diverse branches of the Anglican Communion begin to slight the particulars of their own local histories in favour of a romanticised pedigree of Celts, cathedrals and kings. Nevertheless, the English reformers repeatedly stressed that theirs was not a new church, but one that had its origins in earliest centuries of the faith. And while a majority of the Communion no longer confuses being Anglican with being English, we may still find considerable pleasure in claiming these stories as part of our family lore. The Church and History 1. Why do we study history? What do these stories have to do with us? What was your favourite part of the video? Why? 2. What makes you a Christian? Can you be a Christian by yourself? What are the essential components of the Christian life? 3. -

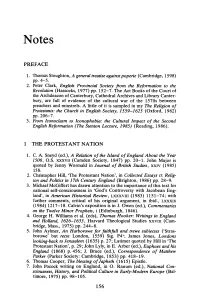

Preface 1 the Protestant Nation

Notes PREFACE 1. Thomas Stoughton, A general treatise against poperie (Cambridge, 1598) pp.4-5. 2. Peter Clark, English Provincial Society from the Reformation to the Revolution (Hassocks, 1977) pp. 152-7. The Act Books of the Court of the Archdeacon of Canterbury, Cathedral Archives and Library Canter bury, are full of evidence of the cultural war of the 1570s between preachers and minstrels. A little of it is sampled in my The Religion of Protestants: the Church in English Society, 1559-1625 (Oxford, 1982) pp.206-7. 3. From Iconoclasm to Iconophobia: the Cultural Impact of the Second English Reformation (The Stenton Lecture, 1985) (Reading, 1986). 1 THE PROTESTANT NATION 1. C. A. Sneyd (ed.), A Relation of the Island of England About the Year 1500, O.S. XXXVII (Camden Society, 1847) pp. 20-1. John Major is quoted by Jenny Wormald in Journal of British Studies, XXIV (1985) 158. 2. Christopher Hill, 'The Protestant Nation', in Collected Essays II: Relig ion and Politics in 17th Century England (Brighton, 1986) pp. 28-9. 3. Michael McGiffert has drawn attention to the importance of this text for national self-consciousness in 'God's Controversy with Jacobean Eng land', in American Historical Review, LXXXVIII (1983) 1151-74; with further comments, critical of his original argument, in ibid., LXXXIX (1984) 1217-18. Calvin's exposition is in J. Owen (ed.), Commentaries on the Twelve Minor Prophets, I (Edinburgh, 1846). 4. George H. Williams et al. (eds), Thomas Hooker: Writings in England and Holland, 1626-1633, Harvard Theological Studies XXVIII (Cam bridge, Mass., 1975) pp. -

Martyrology 12 09 19

Martyrology An Anglican Martyrology - for the British Isles 1 of 160 Martyrology Introduction The base text is the martyrology compiled by Fr. Hugh Feiss, OSB. Copyright © 2008 by the Monastery of the Ascension, Jerome, ID 83338 and available online at the website of the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. The calendars of each of the three Anglican churches of the British isles contain varied group commemorations, I suggest these entries are read only in the province where they are observed and have indicated that by the use of italics and brackets. However, people, particularly in the Church of England, are woefully ignorant of the history of the other Anglican churches of our islands and it would be good if all entries for the islands are used in each province. The Roman dates are also indicated where these vary from Anglican ones but not all those on the Roman Calendar have an entry. The introductions to the saints and celebrations in the Anglican calendars in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales in Exciting Holiness, ed. Brother Tristam SSF, The Canterbury Press, 1997, have been added where a saint did not already appear in the martyrology. These have been adapted to indicate the place and date of death at the beginning, as is traditional at the reading of the martyrology. For the place of death I have generally relied on Wikipedia. For Irish, Welsh and Scottish celebrations not appearing in Exciting Holiness I have used the latest edition of Celebrating the Saints, Canterbury Press, 2004. These entries are generally longer than appear in martyrologies and probably need editing down even more than I have done if they are to be read liturgically. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Life And

LANCELOT ANDREWES’ LIFE AND MINISTRY A FOUNDATION FOR TRADITIONAL ANGLICAN PRIESTS by Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. B.B.A, Georgia State University, 1983 A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina September 2014 Accepted: Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Donald Fortson, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Lancelot Andrewes Life and Ministry A Foundation for Traditional Anglican Priest Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. This thesis explores Lancelot Andrewes’ life and ministry as an example for Traditional Anglican Priests. An introduction and biography are presented, followed by an examination of his prayer life, doctrine, and liturgy. His prayer life is examined through his private prayers, via tract number 88 of the Tracts for the Times, daily prayers, and sermons. The second evaluation made is of Andrewes’ doctrine. A review of his catechism is followed by his teaching of the Commandments. His sermons are examined and demonstrate his desire and ability to link the Old Testament and the New Testament through Jesus Christ and a review is made through examining his sermons for the different church seasons. Thirdly, Andrewes’ liturgy is the focus, as many of his practices are still used today within the Traditional Anglican Church. His desire for holiness and beauty as reflected in his Liturgy is seen, as well as his position on what should be allowed in the worship of God. His love for the Eucharist is examined as he defends the English Church’s use of the term “Real Presence” in its relationship to the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist. -

Services and Music 2019

THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY OF LINCOLN 13 – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Canon-in-Residence: The Precentor SUNDAY 13 OCTOBER: SEVENTEENTH SUNDAY AFTER TRINITY THURSDAY 17 OCTOBER Ignatius, bishop, martyr, c.107 0745 Litany BCP 0730 Mattins CW St Hugh’s Shrine 0800 Holy Communion Order Two [BCP] 0800 Holy Communion Order One Ringers’ Chapel 0930 SUNG EUCHARIST Order One 1230 Holy Communion BCP St Hugh’s Shrine Jackson in G Pss 11, 150 1730 EVENSONG BCP Villette Hymne à la Vierge See order of service Walmisley in D minor Byrd Responses Sermon: The Precentor Pss 98, 99 Stanford How beauteous are the feet Vierne Toccata in B flat NEH 221, 424 1115 MATTINS BCP Byrd Responses Stanford in B flat Ps 143 FRIDAY 18 OCTOBER Luke the Evangelist Stanford Pray that Jerusalem may have peace and felicity NEH 366 0730 Mattins CW St Hugh’s Shrine Elgar Allegretto pensoso Op 14 0800 Holy Communion Order Two [BCP] Russell Chantry Chapel 1230 Holy Communion Order One St Hugh’s Shrine 1100 Funeral Service of Andrew Taylor 1400 A Time to Remember St Hugh’s Shrine 1200 Litany CW Longland Chapel A service for those who have lost a child before birth 1230 Holy Communion Order One St Hugh’s Shrine or in infancy 1730 SOLEMN EVENSONG BCP 1545 EVENSONG BCP Ireland Vesper hymn Lloyd Responses Ps 103 Gibbons The second service Lloyd Responses Chilcott The three choirs service NEH 213, 194 Batten O sing joyfully Ps 144 Tomkins Almighty God, the fountain of all wisdom OH 2, NEH 413 Pott Toccata SATURDAY 19 OCTOBER Henry Martyn, translator, missionary, 1812 MONDAY