Subnational Transnational Networking and the Continuing Process of Local Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science and Governance of the Channel Marine Ecosystem”

Forum “Science and Governance of the Channel Marine Ecosystem” PEGASEAS partners and their logos PEGASEAS projects and their logos Citation: Evariste E., Dauvin J.-C., Claquin P., Auber A., Winder A., Thenail B., Fletcher S., Robin J.-P. (ed.). 2014 Trans-Channel forum proceedings “Science and governance of the Channel marine ecosystem”. INTERREG IV A Programme, Université de Caen Basse-Normandie, Caen, France, 160 pp. www.pegaseas.eu 1 1 Forum “Science and Governance of the Channel Marine Ecosystem” TRANS-CHANNEL FORUM PROCEEDINGS “SCIENCE AND GOVERNANCE OF THE CHANNEL MARINE ECOSYSTEM” 2nd and 3rd July 2014 University of Caen Basse-Normandie Organisation committee 1 Forum “Science and Governance of the Channel Marine Ecosystem” Table of content Simplified programme of the Forum .................................................................................... 3 PEGASEAS Project, The 2nd forum and its context ............................................................. 5 Editorial from Steve Fletcher, leader of the PEGASEAS project ...................................... 7 Editorial from the President of the University of Caen Basse-Normandie, Pierre Sineux ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Abstracts of the oral presentations ....................................................................................... 9 Poster list ............................................................................................................................... -

The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities

she'd be free for lunch from 12:45pm-2:30pm or anytime between 4pm-6pm. The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities: The Case of the Seine Axis (Le Havre, Rouen, Paris, Caen) – France Olaf Merk, César Ducruet, Patrick Dubarle, Elvira Haezendonck and Michael Dooms Please cite this paper as: Merk, O., et al. (2011), “The Competitiveness of Global Port-Cities: the Case of the Seine Axis (Le Havre, Rouen, Paris, Caen) - France”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, 2011/07, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kg58xppgc0n-en OECD Regional Development Working Papers, 2011/07 JEL classification: R41, R11, R12, R15, L91, D57 OECD REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT WORKING PAPERS This series is designed to make available to a wider readership selected studies on regional development issues prepared for use within the OECD. Authorship is usually collective, but principal authors are named. The papers are generally available only in their original language, English or French, with a summary in the other if available. The opinions expressed in these papers are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD or the governments of its member countries. Comment on the series is welcome, and should be sent to [email protected] or the Public Governance and Territorial Development Directorate, 2, rue André Pascal, 75775 PARIS CEDEX 16, France. --------------------------------------------------------------------------- OECD Regional Development Working Papers are published on www.oecd.org/gov/regional/workingpapers --------------------------------------------------------------------------- Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or part of this material should be made to: OECD Publishing, [email protected] or by fax +33 1 45 24 99 30. -

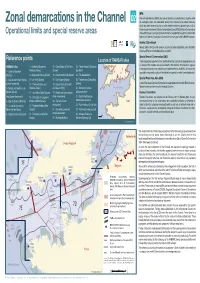

2. Zonal Demarcations in the Channel

PLATE MPA Marine Protected Area (MPA): Any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with Zonal demarcations in the Channel 02 P[Z V]LYSH`PUN ^H[LY HUK HZZVJPH[LK MH\UH ÅVYH OPZ[VYPJHS HUK J\S[\YHS MLH[\YLZ which has been reserved by law or other effective means to protect part or all of the enclosed environment. Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs): Marine Conservation Operational limits and special reserve areas Zones (MCZs) are a new type of Marine Protected Area (MPA) brought in under the UK Marine Act. Marine Conservation Zones will form a key part of the UK MPA network. European Regional Development Fund The European Union, investing in your future Channel Arc Manche integrated strategy Natura 2000 network Fonds européen de développement régional L’Union européenne investit dans votre avenir Natura 2000 is the EU-wide network of protected sites established under the Birds Directive (SPA) and the Habitats Directive (SAC) Reference points Special Area of Conservation (SAC) Location of RAMSAR sites (ZP[LKLZPNUH[PVUZWLJPÄLKPU[OL/HIP[H[Z+PYLJ[P]L,HJOZP[LPZKLZPNUH[LKMVYVUL 26 6 or mores of the habitats and species listed in the Directive. The Directive requires RAMSAR sites )LUÅLL[ :V\[OLUK *OLZPS)LHJO ;OL-SLL[ ;OHUL[*VHZ[ :HUK^PJO United Kingdom 9 8 27 10 7 a management plan to be prepared and implemented for each SAC to ensure the Marshes (Essex) (Dorset) bay (Kent) 21 24 1 - Golfe du Morbihan 25 30 23 favourable conservation status of the habitats or species for which it was designated. 20 22 (Brittany) 8 - Blackwater Estuary (Essex) 16 - Dorset heathlands (Dorset) ;OL:^HSL2LU[ 19 12 14 16 11 5 Special Protection Area (SPA) 9 - Lee Valley (Essex) 17 - Exe Estuary (Devon) 25 - Thursley and Ockley Bog 17 15 29 2 - Baie du Mont Saint-Michel 28 13 (Lower-Normandie) 10 - Thames Estuary and 18 - Isles of Scilly (Cornwall (Surrey) 4 A site of European Community importance designated under the Wild Birds Directive. -

Subnational Transnational Networking and the Continuing Process of Local-Level Europeanization

Subnational transnational networking and the continuing process of local level Europeanization This is an accepted version (prior to editing) of an article published in European Urban and Regional Studies. Definitive citation: Huggins, C. (2018). Subnational transnational networking and the continuing process of local-level Europeanization. European Urban and Regional Studies, 25(2), 206-227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776417691564. Abstract One of the features of local level Europeanization has been the emergence of transnational networking (TN) undertaken by subnational authorities (SNAs). This activity, which received much attention during the 1990s, enables SNAs to take advantage of the opportunities created by European integration. However empirical analyses of TN are lacking, despite European integration and the wider context SNAs find themselves within evolving. Consequently little remains understood about how SNAs engage in TN and how they are affected by Europeanization pressures. Using the case of TN undertaken by SNAs in South East England and Northern France, this article finds that Europeanization has created more opportunities for SNAs to engage at the European level. SNAs have, in turn, taken advantage of these opportunities, leading to increased participation in TN. However SNAs’ approaches to TN are not uniform. Engagement remains marked by differentiation as local level factors, such as local strategy and political objectives, affect how SNAs participate in TN. This differentiation is likely to become increasingly marked -

KCC International Activities 2010

KCC International Activities Annual Report 2010/11 International Kent Global Reach – Local Benefit Contents Foreword Highlights of 2010 – 11 Summary of Activities 1. Helping the Kent economy to grow − EU Funding − Upcoming projects − Locate in Kent − Kent International Business (KIB) − Kent Tourism 2. Partnership Working −−− Partnership with Nord-Pas de Calais −−− Trans-Manche Metro −−− Kent partnership with The Gambia −−− Local partnerships −−− The Health and Europe Centre 3. Supporting a High Quality of Life for Kent Residents −−− 2012 Olympics −−− Open Golf −−− Kent Youth Service −−− Families and Social Care −−− Pascal 4. Conclusions −−− Maintaining an outward-looking focus −−− EU Funding after 2013 Annex 1 ‘Where’s the Money Gone?’ – EU Funding secured in Kent 2007 – 13 Annex 2 ‘What’s the Money Done?’ – Some examples of project outputs and achievements Foreword KCC’s Medium Term Plan to 2014/15 ‘Bold Steps for Kent’, declares that ‘KCC will remain international in focus’, emphasising ‘the strong international ties in the USA and Europe which have been important to learning and innovation in service delivery’. It also confirms KCC’s intention to maintain its position as ‘one of the leading local authorities in the UK at using its influence to maximise funding from EU programmes into Kent.’ The last year has also, of course, continued to be dominated by heavy pressure on public funding and budgetary reductions within the County Council. Such domestic pressures might have made it more difficult for KCC to maintain an outward-looking focus and international profile. However, the contribution of EU funding to business priorities and the identification of European best-practice and collaborative working to improve performance makes this activity even more important in the current climate. -

Marine Governance in the English Channel (La Manche): Linking Science and Management ⇑ G

Marine Pollution Bulletin xxx (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Marine governance in the English Channel (La Manche): Linking science and management ⇑ G. Glegg a, , R. Jefferson a,b, S. Fletcher a a Centre for Marine and Coastal Policy Research, Plymouth University, Drake Circus, Plymouth PL4 8AA, UK b RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK article info abstract Article history: The English Channel is one of the world’s busiest sea areas with intense shipping and port activity Available online xxxx juxtaposed with recreation, communications and important conservation areas. Opportunities for marine renewable energy vie with existing activities for space. The current governance of the English Channel is Keywords: reviewed and found to lack integration between countries, sectors, legislation and scientific research. English Channel Recent developments within the EU’s marine management frameworks are significantly altering our Marine approach to marine governance and this paper explores the implications of these new approaches to Governance management of the English Channel. Existing mechanisms for cross-Channel science and potential bene- Ecosystem approach fits of an English Channel scale perspective are considered. In conclusion, current management practices Marine spatial planning Integration are considered against the 12 Malawi Principles of the ecosystem approach resulting in proposals for enhancing governance of the region through science at the scale of the English Channel. Ó 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). -

KCC International Activities Annual Report 2009 -10 PDF

By: Alex King, Deputy Leader Alan Marsh, Cabinet Member for Public Health and Innovation, Deputy Cabinet Member for International David Cockburn, Executive Director, Strategy, Economic Development & ICT David Oxlade, Head of Research, Strategy and International To: Corporate Policy Overview and Scrutiny Committee - 24 September 2010 Subject: KCC International Activities Annual Report 2009 -10 Classification: Unrestricted 1. Introduction 1.1. Kent County Council’s International Strategy highlights the importance of Members being fully informed about international work in Kent. 1.2. As part of this commitment, the attached fifth International Activities Annual Report highlights examples from the range of international work undertaken across KCC and the county over the past year 1.3. This year’s Report reflects continuing emphasis and success in achieving a number of high value EU projects in support of KCC Directorate and Kent priorities and in helping Kent SMEs to ‘internationalise’ their business activities 1.4. The Report also provides, for example, an overview of international activities involving young people in the context of developing ‘global citizenship’ as well as international development work supported by the Commonwealth Local Government Forum (CLGF) Recommendation Members are asked to comment on and note the contents of this Report and its Appendix Lead Officer contact : Ron Moys Extension1943 [email protected] KCC International Activities Annual Report 2009/10 International Kent Global-Reach-Local Benefit Contents Foreword Some highlights in 2009-2010 (1) (2) Summary of Activities 1. The Global Economy Kent International Business Study Interreg 2-Seas Trade (‘2ST’) project Locate in Kent 2. Developing Global Citizenship 2010 Eurocamp The 2012 Olympics and Open Golf 2011 International Development – partnership with Ghana European Integration Fund 3. -

Baseline Study of the NOSTRA Project Dover Strait

Baseline Study of the NOSTRA project Dover Strait This document is presented in the name of BIO by Deloitte. BIO by Deloitte is a commercial brand of the legal entity BIO Intelligence Service. The legal entity BIO Intelligence Service is a 100% owned subsidiary of Deloitte Conseil since 26 June 2013. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are purely those of the authors and may not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the partners of the NOSTRA network. The methodological approach that was applied during the baseline study is presented in the final report of the study. The analysis that is provided in this report is based on the data collected and reported by the Nostra partners, a complementary literature review conducted by the consultants, and the results provided by the methodological toolkit developed in the framework of the baseline study. Acknowledgement: This report has received support from the partners of the NOSTRA project of Kent (England) and Pas-de- Calais (France). The authors would like to thank both regions for providing information requested for completing this study. Limitations of the analysis: The consultants faced a limited amount of data. In general, on both sides of the strait, involved partners are facing difficulties in collecting socio-economic data. Baseline study of March 2014 Table of Contents 1 General presentation of the strait ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Geographical area .................................................................................................................... -

Dossier De Presse

Press Kit Dossier de presse EM NORMANDIE March 2015 1 SUMMARY 1-History .................................................................................................................... 3 2-Key figures ............................................................................................................. 5 3-Mission statement and vision .............................................................................. 6 4- Statutes and governance ..................................................................................... 7 5-Portfolio of programmes ....................................................................................... 8 6-Focus on the Grande Ecole Master’s Programme and its strengths .............. 10 7-Centres of expertise ............................................................................................ 15 8-Campuses ............................................................................................................ 16 9-EM Normandie alumni network .......................................................................... 18 2 1-History Thanks to its long-standing tradition and rich history, EM Normandie is a well-established and at the same time modern business school. Created in 1871, the Ecole Supérieure de Commerce du Havre was one of France’s first commercial schools formed as a result of Le Havre Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s desire to train the type of staff local businesses and industries needed in the very international context of what was already a major port in France. -

Maritime Spatial Planning II Through Concrete Examples

27/10/09 Maritime Spatial Planning II through concrete examples Ocean and Policy Research Foundation, 27 October 2009 Yves Henocque, IFREMER-OPRF Visiting Fellow The Brittany Coastal Charter 1 27/10/09 About the double track approach National maritime strategy Inter-regions scale Maritime basins including coastal areas (e.g. Arc Manche) Regions Departements Local initiatives Inter-municipalities scale MARINE ENERGIES IN BRITTANY : IT ALL DEPENDS ON US ! • to develop marine energies in Brittany tackling the energy challenge and contribute to France commitments on renewable energies while promoting local development ; • to define an industrial conversion strategy through promoting and supporting a new industrial activity in regard to the development of a maritime economy, source of wealth and employments; • to create a research and expertise consortium of international rank ; 2 27/10/09 3 27/10/09 4 27/10/09 NATIONAL PREVISIONS (2020) 4 000 MW offshore wind farms= about 400 km² (10 MW/km²) = 16 fields of 50 wind mills (fields of 25 km²) = 25 fields of 30 wind mills (fields of 16 km²) = 50 fields of 15 wind mills (fields of 8 km²) BRITTANY REGION PREVISIONS (2020) 1 000 MW offshore wind farms= about 100 km² = 4 fields of 50 wind mills (fields of 25 km²) = 7 fields of 30 wind mills (fields of 16 km²) = 14 fields of 15 wind mills (fields of 8 km²) 0,5% of Brittany territorial waters Maritime activities sensitivity and potential conflicts with wind farms 5 27/10/09 Synergies between fishers and marine energies production •Fishers’ involvement in areas identification with regard to their marine environment knowledge ; •Projects optimisation with regard to their impact on fishery resources – coupling with fisheries enhancement projects ; •Fishers’ involvement in the installment and maintenance of marine farm fields with regard to their abilities. -

CAMIS Maritime Transport and Intermodality Stage 1 Evidence Review

SEEDA CAMIS Maritime Transport and Intermodality September 2010 Stage 1 evidence review colinbuchanan.com CAMIS Maritime Transport and Intermodality Stage 1 evidence review Project No: 18188-02-1 September 2010 20 Eastbourne Terrace, London, W2 6LG Telephone: 020 7053 1300 Fax: 020 7053 1301 Email : [email protected] Prepared by: Approved by: ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ Jon Hale James Goldman Status: Draft Issue no: 0 Date: 21 September 2010 document2 (C) Copyright Colin Buchanan and Partners Limited. All rights reserved. This report has been prepared for the exclusive use of the commissioning party and unless otherwise agreed in writing by Colin Buchanan and Partners Limited, no other party may copy, reproduce, distribute, make use of, or rely on the contents of the report. No liability is accepted by Colin Buchanan and Partners Limited for any use of this report, other than for the purposes for which it was originally prepared and provided. Opinions and information provided in this report are on the basis of Colin Buchanan and Partners Limited using due skill, care and diligence in the preparation of the same and no explicit warranty is provided as to their accuracy. It should be noted and is expressly stated that no independent verification of any of the documents or information supplied to Colin Buchanan and Partners Limited has been made CAMIS Maritime Transport and Intermodality Stage 1 evidence review Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Study area 1 1.3 -

CAMIS Summary Report

Région Haute Normandie > DESIGN SERVICE ON INNOVATION AND CLUSTERS FOR THE INTERREG CAMIS PROJECT Summary Report – July 2011 Context, objective, methodology Context of the study: This study is part of the CAMIS « Channel Arc Manche Integrated Strategy » project, launched in June 2009 within the framework of the EU INTERREG IVA France (Channel) – England programme. Its aim is to develop and implement an integrated maritime policy in the Channel area whilst fostering concrete co-operation between stakeholders and businesses. Four economic sectors have been particularly identified (at least in a first instance): Renewable Marine Energy / Marine leisure / Management of the marine environment / Sustainable port operations. Objective of the design service (French part of a Franco-British study): Carrying out a report on the support for innovation and maritime clusters in the 5 French regions bordering the English Channel (Bretagne, Basse-Normandie, Haute-Normandie, Picardie, Nord-Pas-de-Calais). The report is divided in 2 parts: - Presentation of the support for innovation in the 5 French Channel regions ; - Identification of the potentialities of maritime clusters. Methodology: three tools were used to support this research: - An online survey amongst the members of several French clusters having maritime related activities and located in the Channel area (in April 2011) ; - Around 10 interviews of stakeholders involved in the support for innovation in the maritime activities of the Channel area (Regional Councils / Regional Innovation Agencies, Competitiveness clusters, hubs, etc.); - Desk study based on a great amount of documents to feed the overall analysis and refine specific approaches, either sector-based or horizontal. Part 1: The support for innovation in the 5 French Channel regions Organisation of support for innovation An inventory of players enabled a fairly exhaustive assessment to be made of the large number of participants in the field of innovation .