A Complete Exegesis of the Historical Section of Daniel Chapter 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

The Maccabees

The Maccabees Written by Steven G. Rhodes Copyright Case# 1-3853893102 Date: Nov 26, 2016 Steven G. Rhodes 1830 NW 1st Ave., Apt D. Gainesville, FL 32603 305-766-5734 941-227-5997 stevengrhodes @yahoo.com REM: Order of Day 8 Chanukah: Circa 1930’s Europe. (hidden until ACT III) REM: WATCH JUDITH MOVIES ON NETFLIX. REM: WATCH ADAM AT SOLSTICE MOVIES OJ NETFLIX REM: WATCH LEVIATHAN MOVIES ON NETFLIX 1 REM PROLOGUE: READ BY NARRATOR (RABBI DALLMAN) 1 Hanukkah is celebrated for eight days beginning on the 25th of Kislev (mid- to late-December). Since Hanukkah falls four days before the new moon (the darkest night of the month) and close to the winter solstice (the longest night of the year), it seems only natural that a key element of this holiday is light. In fact, one of its other names is the "Feast of Lights" (along with "Feast of Dedication" and "Feast of the Maccabees"). The only essential ritual of Hanukkah is the lighting of candles. The Hanukkah candles are held in a chanukkiah, a candelabra that holds nine candles. (The chanukkiah is different from a menorah, which is a candelabra that holds seven candles and is pictured on the official emblem of the State of Israel.) The candle (shammash) in the middle of the chanukkiah is used to light the others. The idea of a seder is of course best known from Passover, where a progression of 15 steps shapes a complicated process that allows us to re-live and re-experience the Exodus from Egypt. In the same way, we are used to daily and Shabbat services flowing through a fixed progression of prayers found in the siddur [prayerbook] (from the same root as seder). -

Episode 108: Mark Part 48—Greater Than the Temple

Episode 108: Mark Part 48—Greater than the Temple As a preview of chapters 11 and 12, where Yeshua/Jesus condemns and increasingly replaces the Temple as the overlap between Heaven and Earth, we’ll be reviewing some of the “greater than” claims about Yeshua in the Bible and talking about the implications of Malachi, Isaiah and 4QFlor, which discusses the important concept of mikdash adam, the living Temple of the Qumran community. If you can’t see the podcast link, click here. This is going to be really different because this teaching is a pre-emptive overview of Mark chapters 11-12, and to a certain extent, all the way through to chapter 16. The story Mark is telling is the title of this teaching—namely, that Yeshua/Jesus is “Greater than the Temple” and He will, in fact, increasingly judge and functionally replace it over the course of these chapters. This is not to say that the Temple was not used, and even used by the disciples after His resurrection but when we look at the functional purpose and meaning of the Temple, Yeshua is going to really put things into perspective for us. I know this may come as a shock to some people but I hope you will hear me out. I have been studying the Temple for years and it is incredibly fascinating and a very difficult area of study, but Mark’s meaning is also very clear. And so, we’re going to explore it and this will even help us understand why, in Revelation, there is no Temple per se—in fact, the entire city is set up as though it is one big communal Temple. -

Historical Jesus 9: Jewish Groups

Historical Jesus 9: Jewish Groups Four Main Jewish Groups “The Jews had for a great while had three sects of philosophy peculiar to themselves; the sect of the Essenes, and the sect of the Sadducees, and the third sort of opinions was that of those called Pharisees;…But of the fourth sect of Jewish philosophy, Judas the Galilean was the author.” (Josephus, Antiquites of the Jews 18.11, 23) Two centuries before Jesus’ began his ministry, a Greek empire ruled over the land of Israel. The empire outlawed the Law of Moses (Torah) and defiled the Temple by sacrificing a pig to an idol there. This caused a revolution led by the Hasmonean family who presided over Israel from 167-63 bc. 1 They won their religious freedom and eventually political freedom. During this period, several groups emerged including the Pharisees, Essenes, and Sadducees. 2 Pharisees and Sadducees in the Hasmonean Period 3 167 - Mattathias initiated revolution --- military leader --- 166 4 167 -160 Judah the captured and cleansed son of Mattathias military leader --- Maccabee Temple 160 -143 Jonathan Apphus achieved religious son of Mattathias high priest possibly instigated freedom Essenes to withdraw 142 -135 Simon Thassi achieved political freedom son of Mattathias high priest --- 134 -104 John Hyrcanus minted coins, conquered son of Simon high priest supported Pharisees Samaria, Idumea then Sadducees 104 -103 Judah Aristobulus conquered Galilee son of Hyrcanus king & high infuriated Pharisees priest by claiming kingship 103 -76 Alexander conquered Iturea, Gaza brother -

Editor:Sam. Eisikovits [email protected]

1 בס''ד נפלאות הבריאה Chanukkah Editor:Sam. Eisikovits [email protected] 2 Chanukkah Hanukkah (/ˈhɑːnəkə/ HAH-nə- ,חֲנּוכָּה ḥanuká, Tiberian: ḥanuká, usually spelled חֲנֻכָּה :kə; Hebrew pronounced [χanuˈka] in Modern Hebrew, [ˈχanukə] or [ˈχanikə] in Yiddish; a transliteration also romanized as Chanukah or Ḥanukah) is a Jewish festival commemorating the rededication of the Second Temple in Jerusalem at the time of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire. It is also known as the Festival of .(ḥag ha'urim ,חַג הַ אּורִ ים :Lights (Hebrew Hanukkah is observed for eight nights and days, starting on the 25th day of Kislev according to the Hebrew calendar, which may occur at any time from late November to late December in the Gregorian calendar. The festival is observed by lighting the candles of a candelabrum with nine branches, called a menorah (or hanukkiah). One branch is typically placed above or below the others and its candle is used to light the other eight ,שַמָּ ש :candles. This unique candle is called the shamash (Hebrew "attendant"). Each night, one additional candle is lit by the shamash until all eight candles are lit together on the final night of the festival. Other Hanukkah festivities include playing the game of dreidel and eating oil- based foods, such as latkes and sufganiyot, and dairy foods. Since the 1970s, the worldwide Chabad Hasidic movement has initiated public menorah lightings in open public places in many countries. Although a relatively minor holiday in strictly religious terms, Hanukkah has attained major cultural significance in North America and elsewhere among secular Jews as a Jewish alternative to Christmas, and is often celebrated correspondingly fervently. -

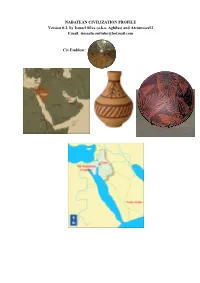

NABATEAN CIVILIZATION PROFILE Version 0.2, by Ismael Silva (A.K.A

NABATEAN CIVILIZATION PROFILE Version 0.2, by Ismael Silva (a.k.a. Aghilas) and Atenmeses52 Email: [email protected] Civ Emblem: • Historical Period: Although the Nabataeans were literate, they left no lengthy historical texts. However, there are thousands of inscriptions still found today in several places where they once lived; including graffiti and on their minted coins. The first historical reference to the Nabataeans is by Greek historian Diodorus Siculus who lived around 30 BC, but he includes some 300 years earlier information about them. • The Twelve Sons of Ishmael: Nebaioth, Qedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, Mishma, Dumah, Massa, Hadad, Tema, Jetur, Naphish, Kedemah. • Civilization Overview: The Nabataeans, also Nabateans, were an Arab people who inhabited northern Arabia and the Southern Levant, and whose settlements, most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu, now called Petra, in AD 37 – c. 100, gave the name of Nabatene to the borderland between Arabia and Syria, from the Euphrates to the Red Sea. Their loosely controlled trading network, which centered on strings of oases that they controlled, where agriculture was intensively practiced in limited areas, and on the routes that linked them, had no securely defined boundaries in the surrounding desert.Trajan conquered the Nabataean kingdom, annexing it to the Roman Empire, where their individual culture, easily identified by their characteristic finely potted painted ceramics, became dispersed in the general Greco-Roman culture and was eventually lost. They were later converted to Christianity. Jane Taylor, a writer, describes them as "one of the most gifted peoples of the ancient world". • Notes on Warfare: Hence we come to a lightly armoured but swift-moving force which was used for raiding or fighting off raiders. -

Thy Kingdom Come: a Sketch of Christ's Church in History – Book I

THY KINGDOM COME A SKETCH OF CHRIST’S CHURCH IN HISTORY Book I : Christ’s Church in its Formation and Jewish Dispensation Compiled and edited by J. Parnell McCarter “our fathers were under the cloud, and all passed through the sea; and were all baptized unto Moses in the cloud and in the sea; and did all eat the same spiritual meat; and did all drink the same spiritual drink: for they drank of that spiritual Rock that followed them: and that Rock was Christ.” – I Corinthians 10:1-4 Dedicated to the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland. As one branch of Christ’s Church here on Earth, she has sought to faithfully proclaim the historic reformed and Biblical faith. Compiled and edited by J. Parnell McCarter ©2001 J. Parnell McCarter. All Rights Reserved. 6408 Wrenwood Jenison, MI 49428 (616) 457-8095 The Puritans’ Home School Curriculum www.puritans.net 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Timeline…………………………… p. 4 Chapter 1 : The Church in History……………p. 5 Chapter 2 : The Promise to the Faithful………p. 8 Chapter 3 : The Patriarchs…………………….p.12 Chapter 4 : The Years in Egypt………………p. 15 Chapter 5 : The Church in the Wilderness……p. 19 Chapter 6 : The Church in Canaan Led by Judges………..p. 25 Chapter 7 : The Kingdom of Israel……….p. 29 Chapter 8 : The Kingdom of Judah………p. 34 Chapter 9 : The Kingdom of Samaria……..p. 37 Chapter 10 : Nineveh…………………….p. 41 Chapter 11 : The Captivity…………………p. 46 Chapter 12 : Babylon………………….p. 50 Chapter 13 : Cyrus………………….p. 54 Chapter 14: The Rebuilding of the Temple………..p. -

Download Slides

“The days are coming," declares the Sovereign Lord, “when I will send a famine through the land — not a famine of food or a thirst for water, but a famine of hearing the words of the Lord.” -Amos 8:11 “Oh, that one of you would shut the temple doors, so that you would not light useless fires on my altar!” -Malachi 1:10 “For my part, I assure you, I had rather excel others in the knowledge of what is excellent, than in the extent of my power and dominion.” ~Plutarch, Life of Alexander “And when the book of Daniel was showed him, wherein Daniel declared that one of the Greeks should destroy the empire of the Persians, he supposed that himself was the person intended; and he was then glad.” Josephus, Antiquities 11:8:5 “The shaggy goat is the king of Greece, and the large horn between his eyes is the first king. The four horns that replaced the one that was broken off represent four kingdoms that will emerge from his nation but will not have the same power.” -Daniel 8:21-22 -Robs the Temple -Ends the Daily Sacrifice -Forbids Circumcision -Forbids Assembly for Prayer -Forbids Possession of Scripture -Sacrifice of Pig upon the Altar -Forces Jews to eat the flesh of pigs -Incites Rebellion Revolt Led by Mattathias the Priest John (Gaddi) Simon (Thassi) Judas (Maccabeus) Eleazar (Avaran) Jonathan (Apphus) Commissioned to clear the seas of piracy Resolves the Civil War between the Sadducees and Pharisees Conquest of Jerusalem “Go and make a careful search for the child. -

New Evidence for the Dates of the Walls of Jerusalem in the Second Half of the Second Century BC

ELECTRUM * Vol. 26 (2019): 25–52 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.19.002.11205 www.ejournals.eu/electrum NEW EVIDENCE FOR THE Dates OF THE WALLS OF JERUSALEM IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SECOND CENTURY BC Donald T. Ariel Israel Antiquities Authority Abstract: Alongside a critique of a new analysis of Josephus’ long account of Antiochus VII Sidetes’ siege of Jerusalem in his Antiquities, this paper presents new archaeological support for the conclusion that, at the time of the siege, the “First Wall” enclosed the Southwestern Hill of the city. Further examination of the stratigraphic summaries of the Hellenistic fortification system at the Giv‘ati Parking Lot proposes that the system constituted part of the western city-wall for the City of David hill. The addition of a lower glacis to the wall was made in advance of Sidetes’ siege. In other words, in addition to the “First Wall” protecting the western side of an expanded Jerusalem, John Hyrcanus also reinforced the City of David’s wall, as an additional barrier to the Seleucid forces. Later, after the high priest’s capitulation to Sidetes (132 BC) and the king’s death in Media (129 BC), Hyrcanus again reinforced the same fortification with an upper glacis, which never was tested. Keywords: Jerusalem, “First Wall”, Southwestern Hill, Giv‘ati Parking Lot, Antiochus VII Sidetes, John Hyrcanus. Introduction In understanding human settlement, size is a basic jumping-off point. However, for a large ancient settlement to be defined as a city, it must also have a defensive wall around it. Tracing the growth and decline of a city has often been undertaken by measur- ing the amount of land within its city-walls. -

![581 Appendix 3B, II, Attachment 5 CHARTED EXPLORATION of FAMILIAL RELATIONSHIPS JOHANAN/JONATHAN/[Y]JEHOHANAN/JOHN to JOHN HYRCA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2493/581-appendix-3b-ii-attachment-5-charted-exploration-of-familial-relationships-johanan-jonathan-y-jehohanan-john-to-john-hyrca-6152493.webp)

581 Appendix 3B, II, Attachment 5 CHARTED EXPLORATION of FAMILIAL RELATIONSHIPS JOHANAN/JONATHAN/[Y]JEHOHANAN/JOHN to JOHN HYRCA

Appendix 3B, II, Attachment 5 CHARTED EXPLORATION OF FAMILIAL RELATIONSHIPS JOHANAN/JONATHAN/[Y]JEHOHANAN/JOHN TO JOHN HYRCANUS I Note: Source Quotations with citations are given in Appendix 3B, II, Attachments 4 and 6. Antecedents, Attachment 2 Sanballat / / / [ / + ? --------------------------------------------------------------Johanan/Jonathan//Y[Jehohanan/John-----------+--------Daughter / Delaiah and 1 [ / + ? / / + ? [ / + ? / / + ? / / Shemaiah ] 2 3 / [Daughter / / / [Manasseh? ] fn. / 4 / + Manasseh? ] / / / / / Jaddua / Jaddua / / / + ? / / + ? Nicasio + Manasseh 5 / / / [?Daughter + Manasseh? ] 6 [? + a Jesus ?Daughter-----+-----? Onias I [------+----Daughter? ] / / + ? / + ? or / 7 [?Daughter +-------?: Eleazar [#1] Simon the Just / / / + ? / +? /-----------+ ?----------/ / + ? 8 9 [Sirach? / Onias II Jesus/Jason Menelaus/ [Lysimachus? ] Daughter [ / + ? / / / Onias III + Simon of 10 [Jesus of Ecclesiasticus? ] -------------continued next page----------- Bilgah 1 Sanballat sons, or sons-in-law? 2 ”Jaddua had a brother [or brother-in-law?] whose name was Manasseh.” 3 Relates to fn. 1. 4 Relates to fn. 2. 5 ”Manasseh...was son-in-law to Jaddua.” 6 If Jonathan had this daughter, it may explain differing versions of Ecclesiasticus 50:1: “Simon the high priest, son of Onias” (Cambridge Apocrypha referenced in this work); “Simon the priest, son of Jochanan” (The New American Bible, Wichita, Kansas: Catholic Bible Publishers, 1974-1975 Edition). 7 If Eleazar’s mother was either a sister of Manasseh or a daughter of Johanan, Manasseh could be referred to as Eleazar’s “uncle.” However, it appears that Eleazar only could be referred to also as a brother of Simon if the latter were true, i.e. Johanan’s daughter were mother of Eleazar and Simon; see preceding footnote. 8 Referred to as being “young” when his father Simon died. 9 At one point, ”Menelaus left his brother, Lysimachus” in his place in the high priesthood. -

821 the Undesignated “Brother of Hyrcanus

Appendix 4B, Attachment 1 CHARTED EXPLORATION OF DESCENDANCIES/FAMILIAL RELATIONSHIPS 1 THE ASAMONAEANS/MACCABEES /HASMONAEANS Note: Sources of data are reference-quoted narratives in Appendices 4B I-III unless otherwise cited. Roman numerals that distinguish same-named individuals correspond with those assigned in its internal data. Sequencing of siblings on a line does not indicate chronological order of births. [Continued from Appendix 3B, II, Attachment 5] / Mattathias / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? Judas/Maccabeus / Jonathan/Apphus John/Gaddi/Gaddis Eleazar/Avaran/Auran / ? + ? Simon/Thassi/Matthes / / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? “brother of Daughter Judas [#2] Mattathais / Hyrcanus” + Ptolemy [#2] / Son of Aububus John Hyrcanus I – continued below ? + ? / (Salome-) Alexandra I John Hyrcanus I / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? ? + ? Judas/Aristobulus I Antigonus I Alexander I Unnamed son Unnamed son / Left widow, “Salome,” Janneus Absalom, who the Greeks + “uncle and father-in-law called “Alexandra” [I] Alexandra I (Aristobulus I’s widow) of Aristobulus II” / / / / + ? ? Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II [-----------------------------+ Daughter] / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? / + ? 2 3 Alexandra II ----+---Alexander II Antigonus II Alexandra III Unnamed 4 / / / / + ? + Philippion Daughter? A Daughter Aristobulus III MARIAMNE/MIRIAM I Unnamed + Ptolemy Menneus 5 + Pheroras + Herod the Great Daughter (Philippion’s father) Continued in 4 B, Attachment 2 + Antipater III betrothal [? + Ptolemy, son of [4B, Att. 2, B] / Menneus Lysanias] The undesignated “brother of Hyrcanus [I]” was sent to Antiochus VII by Jerusalem leaders as a hostage. AJ XIII.VIII.3; BJ I.II.3. Judas #2 and Mattathais #2 both were assassinated with their father, high priest Simon Matthes, by Ptolemy, son of Abubus, in 134 b.c. Aristobulus I, Hyrcanus I’s “eldest son.” Antigonus I, son of Hyrcanus I, was slain by Judas/Aristobulus I. -

Definitions Are from the Harper Collins Bible Dictionary (Condensed Edition), Edited by Mark Allan Powell, 2009

Definitions are from the Harper Collins Bible Dictionary (condensed edition), edited by Mark Allan Powell, 2009. Maccabees (mak´uh-beez), a family(properly the Hasmoneans) that provided military, political, and religious leaders for Judea during much of the second and first centuries BCE. Their exploits are recorded in the books of Maccabees, included among what Protestants call the OT Apocrypha and Roman Catholics designate as deuterocanonical writings. The events leading to the rise of the Maccabees were related to attempts by Antiochus IV Epiphanes, Seleucid king of Syria, to foster Hellenism in Judea by tyrannically suppressing Judaism (see 1 Macc. 1–2; 2 Macc. 5–7). The arrival of officers to carry out Antiochus’s decrees at the village of Modein, where an aged priest named Mattathias lived with his five sons (John “Gaddi,” Simon “Thassi,” Judas “Maccabeus,” Eleazar “Avaran,” and Jonathan “Apphus”), gave occasion for the outbreak of a spontaneous revolt that was to turn into a full-scale war. Mattathias died soon after the beginning of the revolt, leaving military leadership in the hands of Judas, whose surname “Maccabeus” (meaning “hammer”) became the source of the popular name given to the family and its followers. Independence was eventually won and Israel was ruled by the Hasmonean dynasty (descendants of Simon, the only son of Mattathias to survive the war). magi (may´ji), sorcerers who, according to Matt. 2, traveled to honor the infant Jesus when he was born. The NRSV’s “wise men” is an inaccurate translation for the Greek magi, which comes from a root meaning “magic.” The magi in Matthew are presented as astrologers who are guided by the stars (2:2) and as Gentiles who do not know scriptural prophecies concerning the location of the Messiah’s birth (2:2–6).