Wiwnewsletter25-December-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generate PDF of This Page

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/1042,Exhibition-entitled-Europa-w-Rodzinie-to-open-at-Ognisko-in-London-o n-Sunday-4th.html 2021-09-30, 18:47 19.02.2018 Exhibition entitled “Europa w Rodzinie” to open at Ognisko in London on Sunday 4th March 2018. EXHIBITION Europa w Rodzinie The exhibition will open on Sunday 4th March 2018 at 12.00 noon and will run until 19th March. Ognisko Polskie - The Polish Hearth Club 55 Exhibition Road London SW7 2PN Member Price: Free Non-member Price: Free To celebrate the Centenary of Polish Independence, Ognisko Polskie and the Polish Landowners Association are proud to jointly host an Exhibition entitled “Europa w Rodzinie” to open at Ognisko on Sunday 4th March 2018. The Exhibition pays tribute to a significant sector of Polish Society, the ‘Landed Gentry’ which for centuries constituted the backbone of Poland’s cultural economic and political life. Ognisko Polskie is the natural venue for the exhibition considering its background and patronage. The author of the exhibition is the Polish Institute of National Remembrance, “Instytut Pamieci Narodowej” who kindly agreed to bring it over to London. It was first displayed in the Royal Castle in Warsaw and has subsequently been shown in most of the major cities in Poland. The exhibition traces the achievements and ethos of this social group and its virtual demise in the 20th Century during the period of communist rule. Personalities such as Witold Lutoslawski, Josef Czapski, Witold Gombrowicz, Witold Pilecki are famous figures in the 20th Century, all very different characters and all from Landed Gentry families. -

Graphic Africa Graphic LONDON DESIGN FESTIVAL 2013: DESIGN IS EVERYWHERE

14 – 22 SEPT 2013 LONDONDESIGNFESTIVAL.COM 2013 SEPT 22 Graphic Africa 14 September — 20 October Showcasing over 20 pieces of new contemporary furniture by 16 designers from 10 countries in East, West and Southern Africa. Design Network Africa, a CKU project, looks at the current shifts and exciting developments in design happening now across the continent. See page 199 for details Platform at Habitat 208 King’s Road, SW3 5XP www.habitat.co.uk/platform LONDON DESIGN FESTIVAL 2013: DESIGN IS EVERYWHERE Over the 11 years of the London Design Festival, a vast diversity of local and international design has been showcased and celebrated. This year is no exception, with more than 300 events open to all across the capital. The Festival is a punctuation moment in the year and acts as a reminder that design is all around us, permeating every part of our lives. From the commercial to the conceptual, from the subtle to the spectacular, from the weird to the wonderful, we invite you to enjoy the great breadth of design that the London Design Festival has to offer in 2013. LDF Guide_Layout 1 7/18/13 3:31 PM Page 1 ∞≤√ INTRODUCING ANGELL, WYLLER & AARSETH BRANDS LTD, CLERKENWELL Introduction 5 INTRODUCTION Chairman Director Sir John Sorrell CBE Ben Evans Design is everywhere in London, in In a city like London, it is hard to be Great Britain and across the world. noticed. That is the whole point of the It is so much part of everyday life that Festival, a concentrated time when people take it for granted – except design is very visible. -

Newsletter 57

THE BHUTAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 57 PRESIDENT: SIR SIMON BOWES LYON AUTUMN 2015 Summer visit by Society members Annual Dinner A final reminder to those who have not already booked, that this Dinner will be held on Friday 27 November at The Polish Hearth Club, 55 Prince’s Gate, Exhibition Road, London SW7 2PN. Booking forms were enclosed with the last Newsletter. Please complete and return with payment to the Dinner Secretary, Mark Swinbank. Blessed, or cursed, by the hottest July temperature ever recorded in Britain, members of the Society were welcomed by Sir Simon and Lady Bowes Lyon to St Paul’s Walden Bury for a delightfully informal but informative day. The house, in the family of the Society’s President since 1725, is the place where HM the late Queen Mother grew up and was later home to her brother, David (Simon’s father). From its oldest part, the 18th century Adam style north wing, formal tree-lined allées, each leading the eye to a statue or architectural feature, radiate in the classic French goose-foot pattern. Although the show of flowering shrubs from Simon’s trips to the Himalayas were over, it was the perfect time to see a special Bhutanese tree Cornus capitata in full bloom (or, technically, bract). This provided a good backdrop for the group photograph above. After a light lunch next to a gnarled but magnificent old oak, Caroline showed guests round the house, with its original 18th century plasterwork ceilings and some very recognisable royal pieces: a portrait of the Queen Mother (one half of a pair with that of her brother David), and a rocking horse which had been ridden by the young princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, as seen in a photograph from 1932. -

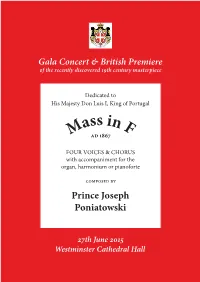

S in F M AD 1867

Gala Concert & British Premiere of the recently discovered 19th century masterpiece Dedicated to His Majesty Don Luis I, King of Portugal ass in F M AD 1867 FOUR VOICES & CHORUS with accompaniment for the organ, harmonium or pianoforte COMPOSED BY Prince Joseph Poniatowski 27th June 2015 Westminster Cathedral Hall 1 H. M. Stanisław August Poniatowski, last King of Poland Stanisław Poniatowski (1667–1762) Casimir Stanislaus August Andrew Michael (1721–1781) (1732–1798) (1735–1773) (1736–1794) Cancellor of Poland Last King of Poland General in Austrian Army Archibishop of Gniezno (1764–1795) Primate of Poland Stanislaw Jozef Antoni (1757–1833) (1763–1813) Treasurer of Lithuania Field Marshal in Napoleon’s Army Jozef Michal Ksawery Franciszek Jan Poniatowski (1816–1873) Born in Rome: Giuseppe Michele Severio Francesco Luci, Principe di Monte Rotondo, Tuscan Plenipotentiary (Brussels 1849, London 1850–53, Paris 1854), Senator French Parliament (1854–1871). Opera Tenor and Composer of 12 Operas and Mass in F In the presence of His Eminence Cardinal Vincent Nichols The Association of Polish Knights of Malta UK supported by The Polish Heritage Society UK and The Embassy of the Republic of Poland presents: Prince Joseph Poniatowski’s Mass in F under the Patronage of His Excellency Mr Witold Sobków Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of The Republic of Poland to The Court of St. James’s ARCHBISHOP’S HOUSE, WESTMINSTER, LONDON SW1P 1QJ Dear Friends, It is a privilege that tonight for the first time Prince Josef Poniatowski’s Mass in “F” is going to be performed here in Westminster Cathedral Hall in London. When I was approached by the Polish Knights of Malta UK and The Polish Heritage Society UK to be Patron of this historic event, I accepted immediately. -

We Shall Remember Them…

We Shall Remember Them… The Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum – PISM (Instytut Polski i Muzeum imienia generała Sikorskiego – IPMS) houses thousands of documents and photographs, as well as museum artifacts, films and audio recordings, which reflect the history of Poland. Materials that relate to the Polish Air Force in Great Britain form part of the collection. This presentation was prepared in May/June 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic when the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum was closed due to lockdown. The materials shown are those that were available to the authors, remotely. • The Battle of Britain lasted from the 10th July until the 31st October 1940. • This site reflects on the contribution and sacrifice made by Polish airmen during those three months and three weeks as they and pilots from many other nationalities, helped the RAF in their defence of the United Kingdom. The first exhibit that one sees on entering the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum is this sculpture. It commemorates the contribution of the Polish Air Force during the second world war and incorporates all the Polish squadrons’ emblems and the aircraft types in which they fought.. In the Beginning….. • The Polish Air Force was created in 1918 and almost immediately saw action against the invading Soviet Army during the Polish-Russian war of 1920. • In 1919 eight American volunteers, including Major Cedric Fauntleroy and Captain Merian Cooper, arrived in Poland and joined the 7th Fighter Squadron which was renamed the “Kosciuszko Squadron” after the 18th century Polish and American patriot. When the 1920-21 war ended, the squadron’s name and traditions were maintained and it was the 111th “Kościuszko” Fighter Escadrille that fought in September 1939 over the skies of Poland. -

Polish Military Leadership in Wwii Conference

POLISH MILITARY LEADERSHIP IN WWII CONFERENCE This conference has been organised in partnership with the British Commission for Military History and the Polish Heritage Society UK, supported by the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland. It is being held at the Royal College of Defence Studies, London on 20th and 21st June 2014. It includes a full assessment of 3 Polish Battlefield Generals (1939-1945), and The Battle of Britain, Polish Air Force 303 Fighter Squadron. General Anders was the commander of the 2nd Polish Corps in Italy 1943–1946, capturing Monte Cassino in the Battle of Monte Cassino, General Maczek, was a Polish tank commander of World War II, whose division was instrumental in the Allied liberation of France by closing the Falaise Gap, resulting in the destruction of 14 German Wehrmacht and SS divisions, General Sosabowski fought in the Battle of Arnhem in 1944 as commander of the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade. The Polish Air Force 303 Fighter Squadron was one of 16 Polish Squadrons in the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War. POLISH MILITARY LEADERSHIP IN THE WWII CONFERENCE General Anders was the commander of the 2nd Polish Corps in Italy 1943–1946, capturing Monte Cassino in the Battle of Monte Cassino. Shortly after the attack on the Soviet Union by Germany on 22 June 1941, Anders who had been imprisoned in Moscow was released by the Soviets with the aim of forming a Polish Army. Following the Mayski-Sikorski agreement signed in London on 30th July, 1941, Stalin agreed to the exodus from the Soviet Union of Anders' men – known as the Anders Army, together with a sizeable contingent of Polish civilians via the Persian Corridor into Iran, Iraq and Palestine. -

London Albertopolis

Albertopolis A free self-guided walk in South Kensington Explore London’s quarter for science, technology, culture and the arts .walktheworld.or www g.uk Find Explore Walk 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed maps 8 Commentary 10 Further information 45 Credits 46 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Walk the World is part of Discovering Places, the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad campaign to inspire the UK to discover their local environment. Walk the World is delivered in partnership by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) with Discovering Places (The Heritage Alliance) and is principally funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor. The digital and print maps used for Walk the World are licensed to RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey. 3 Albertopolis Explore London’s quarter for science, technology, culture and the arts Welcome to Walk the World! This walk in South Kensington is one of 20 in different parts of the UK. Each walk explores how the 206 participating nations in the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games have been part of the UK’s history for many centuries. Along the routes you will discover evidence of how many Olympic and Paralympic countries that have shaped our towns and cities. Prince Albert and Sir Henry Cole had a vision: an area of London dedicated to education and culture. It became a reality 150 years ago in South Kensington, and became fondly known as ‘Albertopolis’ after its royal patron. Albertopolis is home to some of London’s most spectacular buildings, world class museums and premier educational institutions. -

Annual Report 2019 – 2020

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 Acknowledgments | 4 Chairman’s Remarks | 5 About CDPB | 6 Directors and Executive Team | 7 Projects and Highlights | 8 Contact Details | 24 Acknowledgments Our work would not be possible without assistance from many public, private and community partners. We are truly grateful for all the support. Special thanks to: Dr Terry Cross OBE Amanda Campbell MBA Airporter Allstate Northern Ireland ARTIS (Europe) Belfast Live Bespoke Communications British Council Brown O’Connor Communications Centre for Resolution of Intractable Conflict, Harris Manchester College, Oxford Community Relationship Council Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Republic of Ireland Herbert Smith Freehills Ineqe Group Interfrigo Ltd. Japan House London Lagan Investments Northern Ireland Office Polish Cultural Institute in London Smarts St. Benet’s Hall, Oxford The Embassy of the Republic of Poland in the UK The Executive Office Urban Villages Initiative Ulster University Üsküdar University, Istanbul, Turkey Washington Ireland Program 04 Chairman Remarks The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is changing the world we live in and how we adjust to that change will have implications for political and economic stability for years to come. What we do know is that in times of great uncertainty and change, democratic processes are often challenged or undermined, and this can be the seedbed for conflict. This makes the work of the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building (CDPB) even more relevant and necessary. The past year has across the globe. This continues to be an important part been a time of of what CDPB is about as we facilitate conversations and change within CDPB encourage debate on the issues that impact on all our lives itself and I take this at this time. -

The Irish Polish Society Yearbook Rocznik Towarzystwa Irlandzko-Polskiego, Tom VII, 2020

Vol. VII, 2020 The Irish Polish Society Yearbook Rocznik Towarzystwa Irlandzko-Polskiego, tom VII, 2020 Irish Polish Society Towarzystwo Irlandzko - Polskie The Irish Polish Society Yearbook, vol. VII, 2020 Rocznik Towarzystwa Irlandzko-Polskiego, tom VII, 2020 EditedEditorial by: Advisory Jarosław Panel: Płachecki Barry Keane (Peer reviewer) Wawrzyniec K. Konarski (Peer reviewer) Hanna Dowling (Data yearbook) JolantaPatrick Góral-PółrolaQuigley (Linguistic (Peer reviewer)reviewer) Jason Dolan (Digital photography) Mariusz Kamiński (Translation and linguistic reviewer) Call for papers: The Irish Polish Society Yearbook is a refereed journal of the Irish Polish mutual understanding between the Irish and Polish communities. The Irish Polish Society YearbookSociety. Since (IPSY) its editorial first issue policy in 2014 is pluralist it promotes and interdisciplinary. cultural diversity, The integration journal is and exclusively greater dedicated to the publication of high-quality academic articles on the history, society, cultural events, arts, economic and political relationships between Poland and Ireland as well as being a record of activities of the Irish Polish Society and other Polish organisations in Ireland. It provides a forum for critical and creative writing for members of the IPS, academics, writers and other authors and organisations that work towards integration between the two communities in Ireland. All proposals for papers relating to the above areas should be sent to the Editor on e-mail address: [email protected] and should include: the author(s) name, title and Full papers of no more than 6000 words (including notes and references) should begin with affiliation (if any), contact details, paper title and preliminary abstract. a(which short abstractwill be oftranslated). -

Collecting the Show on the Road: Spotlight on Anna Mieszkowska and the Polish Cabaret Archive Author(S): Beth Holmgren Source: the Polish Review, Vol

Collecting the Show on the Road: Spotlight on Anna Mieszkowska and the Polish Cabaret Archive Author(s): Beth Holmgren Source: The Polish Review, Vol. 59, No. 4 (2014), pp. 3-20 Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Polish Institute of Arts & Sciences of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/polishreview.59.4.0003 Accessed: 28-08-2015 06:13 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press and Polish Institute of Arts & Sciences of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Polish Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 152.3.102.242 on Fri, 28 Aug 2015 06:13:38 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Polish Review, Vol. 59, No. 4, 2014 © The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Beth Holmgren Collecting the Show on the Road: Spotlight on Anna Mieszkowska and the Polish Cabaret Archive The article introduces and then gives a transcription of an interview with Anna Mieszkowska, an archivist at the Polish Academy of Sciences who spe- cializes in collecting materials relating to Polish cabaret of the interwar and wartime era. -

Exhibition Road, London Review

Advertisement SPONSORED BY: CHARLES SCHWAB The Trader's Long-Term Investing Plan Trading for the short term and investing for the long haul require different strategies for success. Learn more. Support The Guardian Search jobs Sign in Search US edition Available for everyone, funded by readers Contribute Subscribe News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle More Film Books Music Art & design TV & radio Stage Classical Games The Observer Architecture Advertisement Exhibition Road, London review After years of wrangling, the new Exhibition Road in South Kensington, home to many of Britain's great museums, proves a triumph for the 'shared space' movement Exhibition Road: ‘the route from the tube to the museums, always a tricky one unless you took a long subway, is now a pleasure’. Rowan Moore Sat 28 Jan 2012 19.06 EST 11 16 he first thing to say about the remaking of Exhibition Road in London is how sane it largely is. Its concept is unimpeachable – to make a thoroughfare lined with famous museums and other institutions into a place more pleasant for the 11 million Tpedestrians who visit them each year. Its execution is well-judged, apart from the not-small detail that blind people find it alarming. Yet it has taken 18 years since something along these lines was first put forward, plus £29.2m, a court case and endless consultations, to get to this point. How difficult can it be to lay a pavement? Very, it would seem. The road was first developed following the Great Exhibition of 1851 and has the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum, Imperial College, the Royal Geographical Society and the Goethe Institute along its length, not to mention the Polish Hearth Club and a curious, spiritual-modernist-ish building that houses the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

HRH the DUKE of KENT a Life of Service

HRH THE DUKE OF KENT A Life Of Service CONTENTS Foreword by Damon de Laszlo Chapter 1: His Royal Highness Prince Edward The Duke of Kent KG Chapter 2: Health Service Charities: King Edward VII’S Sister Agnes Hospital Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research Stroke Association Institute of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, University of Birmingham Chest Heart & Stroke Scotland Restore Burn and Wound Research Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Association (ME) Watling Hospital Charitable Trust Watling and District Nursing Home The Royal College of Surgeons of England The Royal Society of Medicine Chapter 3: British Overseas Trade Board Chapter 4: Education The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn The Royal Society The Royal Institution of Great Britain and Royal Institution of Australia (RiAus) Royal Geographical Society University of Surrey and Postgraduate Medical School Cranfield University Cambridge University Scientific Society London Metropolitan University 1 Chapter 5: Youth Education, Work, Disadvantaged and Disabled People Aidis Trust Endeavour Training Edge Foundation Chapter 6: Professions, Business, and Engineering Part 1: Professions and Business Association of Men of Kent and Kentish Men The Institute of Export (IOE) International Trade BCS, The Chartered Institute For IT Chartered Management Institute (CMI) Part 2: Engineering The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) The Institution of Mechanical Engineers Royal Academy of Engineering Engineering Council Chapter 7: Civic Duties and Religious Trusts Borough of King’s Lynn and West