Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 18 February 2020] P669a

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

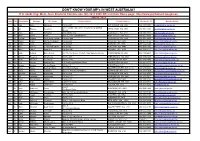

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

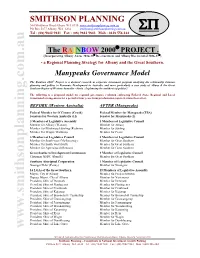

Manypeaks Governance Model

SMITHSON PLANNING 364 Middleton Road Albany WA 6330 www.smithsonplanning.com.au PO Box 5377 Albany WA 6332 [email protected] ΣΠ Tel : (08) 9842 9841 Fax : (08) 9842 9843 Mob : 0428 556 444 The RAINBOW 2000© PROJECT . (Incorporating Albany Anzac 2014-18© Re-enactment and Albany Bicentennial 2026-27©) - a Regional Planning Strategy for Albany and the Great Southern. Manypeaks Governance Model The Rainbow 2000© Project is a doctoral research & corporate investment program analysing the relationship between planning and politics in Economic Development in Australia, and more particularly a case study of Albany & the Great Southern Region of Western Australia – thesis : Is planning the antithesis of politics? The following is a proposed model for regional governance evolution embracing Federal, State, Regional and Local transitional arrangements for a period of four years from proclamation (open elections thereafter). BEFORE (Western Australia) AFTER (Manypeaks) Federal Member for O’Connor (Crook) Federal Member for Manypeaks (TBA) Senators for Western Australia (12) Senator for Manypeaks (1) 3 Members of Legislative Assembly 3 Members of Legislative Council Member for Albany (Watson) Member for Albany Member for Blackwood-Stirling (Redman) Member for Stirling Member for Wagin (Waldron) Member for Piesse 3 Members of Legislative Council 3 Members of Legislative Council Member for South-west (McSweeney) Member for Great Southern Member for South-west (Holt) Member for Great Southern Member for Agricultural (Benson) Member for -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

MINUTES of the ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Held at CITY WEST

MINUTES Of The ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Held At CITY WEST FUNCTION CENTRE West Perth On Friday, 22 September 2017 AGM Minutes 2017 Meeting commenced at 10:00hrs. WELCOME by David Sadler who introduced Andrew Murfin OAM JP, the Master of Ceremonies. Andrew Murfin acknowledged the three gentleman not present today, Hon Max Evans (who is sick), Clive Griffiths who is unable to attend, Cyril Fenn who passed away a couple of months ago. Andrew acknowledged Tony Kristicevic MLA - Member for Carine; only member of parliament present today as all Members of Parliament are always very busy but thank you for coming. He acknowledged, Nita Sadler, Margaret Thomas. APOLOGIES : These were accepted but not read due to the number. Derek & Carla Archer - Archer & Sons, Tom Wallace, Leigh & Linda Thompson - Thompson Funeral Homes, Timothy Bradley- Bowra & O'Dea, Victor Court, Charlotte Howell, Kay Cooper, Brian Mathlin - RWA Board Member, Jessica Shaw MLA, Lisa Baker MLA, Zac Kirjup MP, Reece Whitby MLA, Thelma Van Oyen, Mark Mcgown MLA, Peter Katsambanis MLA, Michelle Roberts MLA, Bill Johnson MLA, Mr Don Punch MLA, Simone McGurk MLA, TERRY REDMAN MLA, Bill Marmion MLA, Jessica Stojkovski MLA, Peter Rundle MP, Cassie Rowe MP, Simon Millman MLA, Lorraine Thompson JBAC, Emily Hamilton MLA, David Michael MLA, Vince Catania MLA, Colin Barnett MLA, Dean Nalder MLA, Jenny Seaton VIP, Carol Pope, Ben Wyatt MLA, Lisa Harvey MLA, Janine Freeman MLA, Shane & Kelly Bradley (Staff), Mike Nahan MLA, John Mcgrath MLA, Paul Papalia MLA, The Honourable Max Evans, Kyran O'Donnell MLA, Rita Saffioti MLA, Mick Murray MLA Nita lead the floor in singing the National Anthem. -

P7906a-7921A Dr Tony Buti

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 12 November 2020] p7906a-7921a Dr Tony Buti; Mr Dean Nalder; Mr Simon Millman; Mrs Lisa O'Malley; Mr Peter Rundle; Mr David Michael; Mr John McGrath; Mr Mick Murray; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Katsambanis; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Shane Love PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE Seventeenth Report — “More Than Just a Game: The Use of State Funds by the WA Football Commission” — Tabling DR A.D. BUTI (Armadale) [10.27 am]: I present for tabling the seventeenth report of the Public Accounts Committee titled “More Than Just a Game: The Use of State Funds by the WA Football Commission”. I also present for tabling the submissions to the inquiry. [See papers 3980 and 3981.] Dr A.D. BUTI: Football, or Aussie Rules, has played a significant role in the lives of Western Australians for more than 130 years. As former Premier Dr Geoff Gallop remarked, “No sport has had such a critical impact on our social and cultural development as Australian Football.” Football is a game that develops tribal loyalties and arouses passions, but it is also more than just a game. As noted by Dr Neale Fong, a former chair of the West Australian Football Commission, the history of football in Western Australia is not only about footballers, clubs and supporters, it also involves relationships with networks of politicians, governments, businesses and personalities involved in the game. The West Australian Football Commission, established in 1989, is the body charged with responsibility for the overall development and strategic direction of football in this state. The creation of the West Australian Football Commission is unique to WA. -

Greyhounds - Namely That Similar to the Recent Changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW

From: Subject: I support an end to compulsory greyhound muzzling Date: Sunday, 28 July 2019 10:52:22 PM Dear Peter Rundle MP, cc: Cat and Dog statutory review I would like to express my support for the complete removal of the section 33(1) of the Dog Act 1976 in relation to companion pet greyhounds - namely that similar to the recent changes in ACT, Victoria and NSW. I believe companion greyhounds should be allowed to go muzzle free in public without the requirement to complete a training programme. I have owned my own greyhound for two years and find the muzzle is not needed or necessary in actual fact I’ve seen other dog breeds aggressively attacking. I support the removal of this law for companion pet greyhounds for the following reasons: 1. Greyhounds are kept as pets in countries all over the world muzzle free and there has been no increased incidence of greyhound dog bites to people, other dogs or animals 2. The RSPCA have found no evidence to suggest that greyhounds as a breed pose any greater risk than other dog breeds 3. Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania are the only Australian states still with this law. All other states (VIC, NSW, QLD, ACT, NT) have removed this law 4. The view supported by veterinary behaviourists is that the behaviour of a particular dog should be based on that individual dogs attributes not its breed 5. As a breed, greyhounds are known for their generally friendly and gentle disposition, even despite their upbringing in the racing industry 6. -

![[ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 9 April 2019] P2258a-2325A Mr Terry Healy; Mr Peter Rundle](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5226/assembly-tuesday-9-april-2019-p2258a-2325a-mr-terry-healy-mr-peter-rundle-3115226.webp)

[ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 9 April 2019] P2258a-2325A Mr Terry Healy; Mr Peter Rundle

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 9 April 2019] p2258a-2325a Mr Terry Healy; Mr Peter Rundle; Mr Chris Tallentire; Mrs Lisa O'Malley; Ms Sabine Winton; Ms Lisa Baker; Mr Ian Blayney; Ms Janine Freeman; Mr David Michael; Mr David Templeman; Mr Tony Krsticevic; Mrs Alyssa Hayden; Mr Shane Love; Mr Bill Johnston LOCAL GOVERNMENT LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL 2019 Second Reading Resumed from 4 April. MR T.J. HEALY (Southern River) [3.39 pm]: I appreciate the opportunity to speak about the Local Government Legislation Amendment Bill. I am a former Gosnells councillor. The entire electorate of Southern River is within the City of Gosnells. It is a fantastic community and a fantastic council. It employs hundreds of staff who deliver an incredible number of services and I am honoured to be able to stand and speak to that. Today, I am going to speak about the importance of the CEO review. The CEO is the most important staff member that the council employs. I am going to talk about gift and travel registers; universal training and how important that is in helping councillors across Western Australia to understand the importance of their role; the mandatory code of conduct; and meeting attendance. I would like to commend the Minister for Local Government for the work that is being done, the chair of the Local Government Act review—the member for Balcatta, I believe—and all local governments and stakeholders for being a part of the discussion and working towards reform in this area, something that has not been done for so long. -

Mr Shane Love; Mr Donald Punch; Mr Ben Wyatt; Mr John Mcgrath; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Sean L'estrange; Ms Lisa Baker

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 12 February 2020] p391a-419a Mr Terry Redman; Mr Peter Rundle; Mr Shane Love; Mr Donald Punch; Mr Ben Wyatt; Mr John McGrath; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Ms Lisa Baker Amendment to Question Ms M.J. DAVIES: I move — That the following words be added after “noted” — and that this house condemns the Labor government for using royalties for regions to prop up the state’s bottom line at the expense of regional Western Australian communities and economies MR D.T. REDMAN (Warren–Blackwood) [3.37 pm]: I rise to talk to the amendment moved by the Leader of the Nationals WA, which reads — and that this house condemns the Labor government for using royalties for regions to prop up the state’s bottom line at the expense of regional Western Australian communities and economies When members opposite went to the election, they laid out a platform supporting royalties for regions. They knew it had currency in regional Western Australia. They knew that regional Western Australia would be watching to understand what they were going to do as it applies to a fund that has fundamentally shifted the sentiment and the culture of regional WA. Those members knew that they would have to have some sort of policy setting on the fund and said, “We support royalties for regions.” When a person from regional WA hears that, they think that the Labor Party supports regional development and royalties for regions. For the first time in their life, Labor members supported all the exciting things that have been happening and planned for in terms of growing, developing and building regional communities. -

WA State Election 2017

PARLIAMENTAR~RARY ~ WESTERN AUSTRALIA 2017 Western Australian State Election Analysis of Results Election Papers Series No. 1I2017 PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN AUSTRALIAN STATE ELECTION 2017 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS by Antony Green for the Western Australian Parliamentary Library and Information Services Election Papers Series No. 1/2017 2017 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, Western Australian Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the Western Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Australian Parliamentary Library. Western Australian Parliamentary Library Parliament House Harvest Terrace Perth WA 6000 ISBN 9780987596994 May 2017 Related Publications • 2015 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2015. • Western Australian State Election 2013 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2013. • 2011 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2011. • Western Australian State Election 2008 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2009. • 2007 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2007 • Western Australian State Election 2005 - Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2005. • 2003 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2003. -

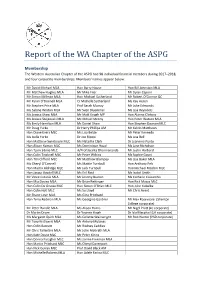

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Western Australian Chapter of the ASPG had 98 individual financial members during 2017–2018, and four corporate memberships. Members’ names appear below: Mr David Michael MLA Hon Barry House Hon Bill Johnston MLA Mr Matthew Hughes MLA Mr Mike Filer Mr Dylan Caporn Mr Simon Millman MLA Hon Michael Sutherland Mr Robert O’Connor QC Mr Kyran O’Donnell MLA Cr Michelle Sutherland Ms Kay Heron Mr Stephen Price MLA Prof Sarah Murray Mr Luke Edmonds Ms Sabine Winton MLA Mr Sven Bluemmel Ms Lisa Reynders Ms Jessica Shaw MLA Mr Matt Keogh MP Hon Alanna Clohesy Ms Jessica Stojkovski MLA Mc Mihael McCoy Hon Peter Watson MLA Ms Emily Hamilton MLA Mr Daniel Shaw Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Mr Doug Yorke Dr Harry Phillips AM Mr Kelvin Matthews Hon Diane Evers MLC Ms Lisa Belde Mr Peter Kennedy Ms Izella Yorke Dr Joe Ripepi Ms Lisa Bell Hon Matthew Swinbourn MLC Ms Natasha Clark Dr Jeannine Purdy Hon Alison Xamon MLC Ms Dominique Hoad Ms Jane Nicholson Hon Tjorn Sibma MLC A/Prof Jacinta Dharmananda Mr Justin Harbord Hon Colin Tincknell MLC Mr Peter Wilkins Ms Sophie Gaunt Hon Tim Clifford MLC Mr Matthew Blampey Ms Lisa Baker MLA Ms Cheryl O’Connell Ms Mattie Turnbull Hon Anthony Fels Hon Martin Aldridge MLC Mr Jack Turnbull Hon Michael Mischin MLC Hon Jacqui Boydell MLC Ms Eril Reid Ms Isabel Smith Mr Vince Catania MLA Mr Jeremy Buxton Ms Catharin Cassarchis Hon Mia Davies MLA Mr Brian Rettinger Hon Rick Mazza MLC Hon Colin De Grussa MLC Hon Simon O’Brien MLC Hon John Kobelke Hon Colin Holt MLC Ms Su Lloyd -

P356a-362A Ms LM Harvey; Mr Chris Tallent

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY ESTIMATES COMMITTEE B — Wednesday, 21 October 2020] p356a-362a Ms L.M. Harvey; Mr Chris Tallentire; Mr Paul Papalia; Mrs Liza Harvey; Mr Peter Rundle; Mr John McGrath; Mr Matthew Hughes; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Chair Division 27: Training and Workforce Development, $430 638 000 — Ms M.M. Quirk, Chair. Mr P. Papalia, Minister for Tourism representing the Minister for Education and Training. Ms A. Driscoll, Director General. Ms G. Husk, Director, Finance. Ms K. Ho, Executive Director, Policy, Planning and Innovation. Mr R. Brown, Executive Director, Service Resource Management. Mr G. Thompson, Executive Director, Corporate. Mr P. Wyles, Director, Service Delivery Strategy. Ms M. Stanley, Director, Training Regulation. [Witnesses introduced.] The CHAIR: Member for Scarborough, you have the call. Ms L.M. HARVEY: My first question relates to new works on page 401. At paragraph 3.2, there is reference to some upgrades for heavy haulage driver training at the South Regional TAFE Collie campus. I just want to know whether the department has identified any skill shortages that are specific to the south west area of the state, including the areas of Vasse, Collie and Bunbury. Is there any detail the minister could provide us with on that? Mr P. PAPALIA: The work that is being done at the TAFE in developing this heavy haulage driving operations skill set course looks at the entire state. It addresses the requirements across the entire state. Collie is a great location for establishing that training. Clearly, there are benefits for the community as it transitions from coal into the future, creating jobs and opportunities around the training centre, but it is not isolated to any one region—both the demand and the requirement. -

![Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 17 May 2017] P196b](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8361/extract-from-hansard-assembly-wednesday-17-may-2017-p196b-5998361.webp)

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 17 May 2017] P196b

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 17 May 2017] p196b-220a Mr Kyran O'Donnell; Ms Emily Hamilton; Mr Mark Folkard; Mr Matthew Hughes; Mr Reece Whitby; Mr John Carey; Mr Peter Rundle ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MR K.M. O’DONNELL (Kalgoorlie) [2.52 pm]: Before I start, Mr Speaker, I found it easier to enter a pub brawl as a police officer than to sit here waiting and sweating to give this speech! The SPEAKER: Sometimes it is like a pub brawl in here. Mr K.M. O’DONNELL: Greetings, Mr Speaker and members. I am extremely proud and honoured to be here today and to have been elected to represent the people of the goldfields in the seat of Kalgoorlie. Let me first acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we are meeting and pay my respects to their elders, past and present. Mr Speaker, I wish to congratulate you on being elected and wish you all the best in your new role. May I say that although we sit on opposite sides of the Parliament, we have something in common—we are both Collingwood supporters. Hopefully, this will not be held against us or my colleague, the member for Hillarys. I also extend my congratulations to all the members on their election after what were, no doubt, hard-fought campaigns. I have met many new people from all sides of politics since coming to Parliament and I believe good friendships will grow from this. I commend parliamentary staff on their professionalism, especially in trying to help us new kids on the block.