INTRODUCTION 0.1. Barwar and Its Assyrian Christian Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The 2018 parliamentary elections, while imperfect, generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Adil Abd al-Mahdi. On December 1, in response to protesters’ demands for significant changes to the political system, Abd al-Mahdi submitted his resignation, which the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) accepted. As of December 17, Abd al-Mahdi continued to serve in a caretaker capacity while the COR worked to identify a replacement in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Numerous domestic security forces operated throughout the country. The regular armed forces and domestic law enforcement bodies generally maintained order within the country, although some armed groups operated outside of government control. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) consist of administratively organized forces within the Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the Counterterrorism Service. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for domestic law enforcement and maintenance of order; it oversees the Federal Police, Provincial Police, Facilities Protection Service, Civil Defense, and Department of Border Enforcement. Energy police, under the Ministry of Oil, are responsible for providing infrastructure protection. Conventional military forces under the Ministry of Defense are responsible for the defense of the country but also carry out counterterrorism and internal security operations in conjunction with the Ministry of Interior. The Counterterrorism Service reports directly to the prime minister and oversees the Counterterrorism Command, an organization that includes three brigades of special operations forces. The National Security Service (NSS) intelligence agency reports directly to the prime minister. -

The Assyrian Tragedy

The Assyrian Tragedy The Assyrian Tragedy Annemasse February 1934 Assyrian International News Agency Books Online www.aina.org 1 The Assyrian Tragedy CONTENTS Preface ..................................................................................................................................................................3 Opinions and Facts ...............................................................................................................................................4 CHAPTER ONE...................................................................................................................................................6 Historical summary of the Assyrian Church and people...................................................................................6 CHAPTER TWO..................................................................................................................................................7 The Assyrians entry into the war 1914-18 ........................................................................................................7 CHAPTER THREE ............................................................................................................................................10 The Mosul Wilayet and the Assyrians ............................................................................................................10 CHAPTER FOUR ..............................................................................................................................................12 -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5 -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Fighting-For-Kurdistan.Pdf

Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq CRU Report Feike Fliervoet Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq Feike Fliervoet CRU Report March 2018 March 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Peshmerga, Kurdish Army © Flickr / Kurdishstruggle Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the author Feike Fliervoet is a Visiting Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit where she contributes to the Levant research programme, a three year long project that seeks to identify the origins and functions of hybrid security arrangements and their influence on state performance and development. -

Security Salary Matrix (.Pdf)

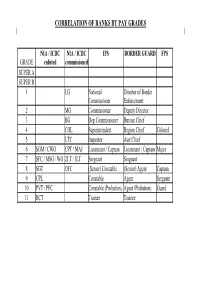

CORRELATION OF RANKS BY PAY GRADES NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER GUARDFPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B 1 LG National Director of Border Commissioner Enforcement 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 3 BG Dep Commissioner Bureau Chief 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 6 SGM / CWO CPT / MAJ Lieutenant / Captain Lieutenant / Captain Major 7 SFC / MSG / WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 8 SGT OFC (Senior) Constable (Senior) Agent Captain 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 11 RCT Trainee Trainee COMPARISON OF RANKS (SHOWING INITIAL STEP INCREMENT) NIA / ICDC NIA / ICDC IPS BORDER FPS GRADE enlisted commissioned SUPER A SUPER B National Dir of Border 1 LG Commissioner Enforcement 1 1 1 2 MG Commissioner Deputy Director 1 1 1 Dep 3 BG Commissioner Bureau Chief 1 1 1 4 COL Superintendent Region Chief Colonel 1 1 1 1 5 LTC Inspector Asst Chief 1 1 1 6 SGM / CWO CAPT/MAJ Lieut / Captain Lieut / Captain Major 1 2 1 6 1 6 1 6 1 7 SFC/MSG/WO 2LT / 1LT Sergeant Sergeant 4 7 8 6 7 6 6 8 SGT OFC (Snr) Constable (Snr) Agent Captain 6 8 6 6 1 9 CPL Constable Agent Sergeant 7 5 5 1 10 PVT / PFC Constable (Probation) Agent (Probation) Guard 4 8 4 4 1 11 Recruit Trainee Trainee 1 4 4 ENTRY LEVEL SALARIES FOR NEW IRAQI ARMY / IRAQI CIVIL DEFENCE CORPS STEPS- SALARIES LISTED IN NEW IRAQI DINAR Grade Enlisted Commission 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 LG 740,000 760,000 780,000 80,0000 820,000 840,000 860,000 880,000 2 MG 574,000 589,000 605,000 620,000 636,000 651,000 -

Assyrians.Pdf

World Directory of Minorities Middle East MRG Directory –> Iraq –> Assyrians Print Page Close Window Assyrians Updated April 2008 Profile An estimated 225,000 Assyrians [US CIRF 2006] comprise a distinct ethno-religious group in Iraq, although official Iraqi statistics consider them to be Arabs. Descendants of ancient Mesopotamian peoples, Assyrians speak Aramaic and live mainly in the major cities and in the rural areas of north- eastern Iraq where they tend to be professionals and businessmen or independent farmers. They are Christians, belonging to one of four churches: the Chaldean (Uniate), Nestorian, Jacobite or Syrian Orthodox, and the Syrian Catholic. Assyrians form a distinct community, but with three origins: (1) those who inhabited Hakkari (in modern Turkey), who were predominantly tribal and whose leaders acknowledged the temporal as well as spiritual paramountcy of their patriarch, the Mar Shimun; (2) a peasant community in Urumiya (see Iran); and (3) a largely peasant community in Amadiya, Shaqlawa and Rawanduz in Iraqi Kurdistan. Historical context Because of its expulsion from the ‘Orthodox' community at Ephesus in 431, the Assyrian Church operated entirely east (hence its title) of Byzantine Christendom, establishing communities over a wide area. But its heartlands were at the apex of the fertile crescent. The Mongol invasions, however, virtually wiped out the Assyrian Church except in limited areas. On the whole the Assyrians co-existed successfully with the neighbouring Kurdish tribes. In Hakkari, Assyrian tribes held Kurdish as well as Assyrian peasantry in thrall, just as Kurdish tribes did, and rival Assyrian tribes would seek allies among neighbouring Kurdish tribes, and vice versa. -

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING the PLACE OF

Abstract Title of Dissertation: NEGOTIATING THE PLACE OF ASSYRIANS IN MODERN IRAQ, 1960–1988 Alda Benjamen, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation Directed by: Professor Peter Wien Department of History This dissertation deals with the social, intellectual, cultural, and political history of the Assyrians under changing regimes from the 1960s to the 1980s. It examines the place of Assyrians in relation to a state that was increasing in strength and influence, and locates their interactions within socio-political movements that were generally associated with the Iraqi opposition. It analyzes the ways in which Assyrians contextualized themselves in their society and negotiated for social, cultural, and political rights both from the state and from the movements with which they were affiliated. Assyrians began migrating to urban Iraqi centers in the second half of the twentieth century, and in the process became more integrated into their societies. But their native towns and villages in northern Iraq continued to occupy an important place in their communal identity, while interactions between rural and urban Assyrians were ongoing. Although substantially integrated in Iraqi society, Assyrians continued to retain aspects of the transnational character of their community. Transnational interactions between Iraqi Assyrians and Assyrians in neighboring countries and the diaspora are therefore another important phenomenon examined in this dissertation. Finally, the role of Assyrian women in these movements, and their portrayal by intellectuals, -

Yakup Hidirsah Massacre of Christians (Assyrians- Nestorians- Chaldeans- Armenians) in Mesopotamia and K U R D S

YAKUP HIDIRSAH MASSACRE OF CHRISTIANS (ASSYRIANS- NESTORIANS- CHALDEANS- ARMENIANS) IN MESOPOTAMIA AND K U R D S A Documentary Study HANNOVER 1997 CONTENTS Introduction Kurds are not from Mesopotamia Syriacs in the Arab, Seljuk and Ottoman Eras Plundering of the Churches and Kurds Bedirhan the Kurdish Emir of Cizre and The Massacre of Christians Support of the Christian Peoples to the Ottoman Empire "Circular" Issued by the Armenian Patriarchy Violation of Kurdish Sheikhs and Aghas Complaint Reports Submitted to the Ottoman Empire "Special Oppression" Exercised by Kurds on Christians Massacres of Christians During the Rebellion of Sheikh Ubeydullah Regiments of Hamidiye and Massacres of Christians Massacre of Christians in World War I Massacre of Christians as quoted by Hori Suleyman Hinno Assimilation Policy of Kurdish Political Movement Conclusion INTRODUCTION Given that the research on the origins of the Christian populations who are known to be the descendants of the old nations and who are called as "Syriacs", "Nestorians", "Chaldeans" has not reached a definite conclusion yet, we deem it early for the time being to state a view on this subject here. Neither do we want to go into the discussions on the views supporting "Assyrians" vs "Aramis" that have emerged in recent years especially between the leftist and rightist Syriac people in Europe. However, we attach great importance to the views of the Syriac historian and the former spiritual leader of all the Syriac people in Turkey, the Metropolitan Filiksinos Hanna Dolapönü (1885-1969) of Mardin concerning the issue. Hanna Dolapönü states that the origin of the Syriac people can not be based on one race only. -

US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army

Intelligence and National Security Vol. 25, No. 1, 76–85, February 2010 US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army JAMES P. PFIFFNER ABSTRACT In May 2003 Paul Bremer issued CPA Orders to exclude from the new Iraq government members of the Baath Party (CPA Order 1) and to disband the Iraqi Army (CPA Order 2). These two orders severely undermined the capacity of the occupying forces to maintain security and continue the ordinary functioning of the Iraq government. The decisions reversed previous National Security Council judgments and were made over the objections of high ranking military and intelligence officers. The article concludes that the most likely decision maker was the Vice President. Early in the occupation of Iraq two key decisions were made that gravely jeopardized US chances for success in Iraq: (1) the decision to bar from government work Iraqis who ranked in the top four levels of Sadam’s Baath Party or who held positions in the top three levels of each ministry; (2) the decision to disband the Iraqi Army and replace it with a new army built from scratch. These two fateful decisions were made against the advice of military and CIA professionals and without consulting important members of the President’s staff and cabinet. This article will first examine the de- Baathification order and then take up the even more far reaching decision to disband the Iraqi Army. Both of these decisions fueled the insurgency by: (1) alienating hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who could not support themselves or their families; (2) by undermining the normal infrastructure necessary for social and economic activity; (3) by ensuring that there was not sufficient security to carry on normal life; and (4) by creating insurgents who were angry at the US, many of whom had weapons and were trained to use them. -

The 2003 Iraq War: Operations, Causes, and Consequences

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (JHSS) ISSN: 2279-0837, ISBN: 2279-0845. Volume 4, Issue 5 (Nov. - Dec. 2012), PP 29-47 www.Iosrjournals.Org The 2003 Iraq War: Operations, Causes, and Consequences Youssef Bassil LACSC – Lebanese Association for Computational Sciences Registered under No. 957, 2011, Beirut, Lebanon Abstract: The Iraq war is the Third Gulf War that was initiated with the military invasion of Iraq on March 2003 by the United States of American and its allies to put an end to the Baath Party of Saddam Hussein, the fifth President of Iraq and a prominent leader of the Baath party in the Iraqi region. The chief cause of this war was the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) that George W. Bush declared in response to the attacks of September 11. The events of this war were both brutal and severe on both parties as it resulted in the defeat of the Iraqi army and the depose and execution of Saddam Hussein, in addition to thousands of causalities and billionsof dollars expenses.This paperdiscusses the overt as well as the covert reasons behind the Iraqi war, in addition to its different objectives. It alsodiscusses the course of the war and its aftermath. This would shed the light on the consequences of the war on the political, economic, social, and humanitarian levels. Finally, the true intentions of the war are speculated. Keywords –Political Science, Warfare, Iraq War 2003, Global War on Terrorism I. INTRODUCTION The Iraq war, sometimes known as the Third Gulf War, began on March 20, 2003 with the invasion of Iraq known as "Iraqi Freedom Operation" by the alliance led by the United States against the Baath Party of Saddam Hussein. -

Sectarianism in the Middle East

Sectarianism in the Middle East Implications for the United States Heather M. Robinson, Ben Connable, David E. Thaler, Ali G. Scotten C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1681 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9699-9 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims attend prayers during Eid al-Fitr as they mark the end of the fasting month of Ramadan, at the site of a suicide car bomb attack over the weekend at the shopping area of Karrada, in Baghdad, Iraq, July 6, 2016. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors.