North Alabama Historical Review, Volume 3, 2013 Article 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Newsletter

Volume XLVI Fall 2017 History Alumni Recognized at Homecoming CATION istory alumni Stephen Dillard ’92 and Jade Acker ’93 and Sciences. According to the nominating committee, Dillard H were among six Samford University graduates honored “has been a wonderful representative of Samford, not only during 2017 homecoming festivities with the university’s through his professional accomplishments, but his annual alumni awards. involvement in his community and with Samford.” Alumni of the Year honorees were nominated by members The Humanitarian of the Year award was established in of the Samford community and selected by a committee of 2016 to recognize Samford graduates of distinction, wide Samford Alumni Association representatives and university respect and acknowledged leadership who have made administrators. They are distinguished in their professional outstanding contributions to better the lives of those around careers, community and church involvement, and in their them by staying true to the Samford mission. ongoing service to Samford. The awards were first presented Three individuals, including a husband and wife team, in 1956, and 120 alumni have been honored since, including were recognized with the Humanitarian of the Year award. several from the history department: J. Wayne Flynt (’61), Jade Acker and Shelah Hubbard Acker are founders Sigurd F. Bryan (’46), Kitty Rogers Brown (’01), Mary Ann and directors of Refuge and Hope International, a multifaceted Buffington Moon (’05), James Huskey (’69), and Houston ministry based in Kampala, Uganda, which they founded in Estes (’04), to name a few. 2004. They serve through the missions auspices of the Joel Brooks ’99 and Stephen Dillard ’92 have been named Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. -

"Fraternities, Sororities, Acceptance, Belonging, Otherness, Rejection" Wayne Flynt, Auburn University Summersell Lecture Series

"Fraternities, Sororities, Acceptance, Belonging, Otherness, Rejection" Wayne Flynt, Auburn University Summersell Lecture Series Wayne Flynt was born in Mississippi and lived there ever so briefly, but he grew up primarily in Alabama. He graduated from Anniston High School, attended Samford University with the intention of joining the ministry, but he turned away from both the ministry and from the state of Alabama in light of the ferocious resistance of those struggling for racial justice found here in the 1960s. So he left Alabama, attended graduate school at Florida State, took a PhD in history, and then, to our eternal benefit, he determined to return to Alabama, where he accepted a teaching position at Samford University in 1965. He taught there for 12 years before leaving in 1977 to become chair of the history department at Auburn University. [laughter] Doesn’t it just sort of stick in your throat just saying it? He remained there until his retirement as a distinguished university professor in 2005. Now, Professor Flynt’s scholarship over his long career has been prolific, remarkable, and immensely important. He has published nearly 100 articles and book chapters. For those of us who write articles and book chapters, that’s kind of jaw dropping. He has authored or coauthored roughly a dozen books, several of which you see out here and are available for sale and signing after the talk. Most of those books center on faith, the less fortunate, politics, and especially on the state of Alabama, for which his deep affection is evident in his writing. His work has justly been recognized over and over again. -

2005-Winter.Pdf

HomecomingHomecoming ’05’05 WhatWhat aa Weekend!Weekend! TheThe SamfordSamford PharmacistPharmacist NewsletterNewsletter pagepage 2929 NewNew SamfordSamford ArenaArena pagepage 5656 features SEASONS 4 Why Jihad Went Global Noted Mid-East scholar Fawaz Gerges traces steps in the Jihadist movement’s decision to attack “the far enemy,” the United States and its allies, after two decades of concentrating on “the near enemy” in the Middle East. Gerges delivered the annual J. Roderick Davis Lecture. 6 Reflections on Egypt Samford French professor Mary McCullough shares observations and insights gained from her participation in a Fulbright-Hays Seminar in Egypt during the summer of 2005. 22 Shaping Samford’s Campus Samford religion professor David Bains discusses the shaping of Samford’s campus from the 1940s on, including an early version planned by descendants of Frederick Olmstead, designer of New York City’s Central Park and the famed Biltmore House and Gardens in North Carolina. 29 The Samford Pharmacist Pharmacy Dean Joseph O. Dean reflects on learning and teaching that touch six decades at Samford in the McWhorter School of Pharmacy newsletter, an insert in this Seasons. Check out the latest news from one of Samford’s oldest component colleges, dating from 1927. 38 Bird’s Eye View of Baltimore That funny fellow inspiring guffaws and groans as the Baltimore Oriole mascot is none other than former “Spike” Mike Milton of Samford. He made almost 400 appearances last year for the American League baseball team, including the New York City wedding -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 49 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 49, Article 1 Number 2 1970 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1970) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 49 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol49/iss2/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 Published by STARS, 1970 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49 [1970], No. 2, Art. 1 FRONT COVER The river front in Jacksonville in 1884. The view is looking west from Liberty Street. The picture is one of several of Jacksonville by Louis Glaser, 1 and it was printed by Witteman Bros. of New York City. The series of 2 /2'' 1 x 4 /2'' views were bound in a small folder for sale to visitors and tourists. This picture is from the P. K. Yonge Library of Florida History, University of Florida. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol49/iss2/1 2 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49, Number 2 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Volume XLIX, Number 2 October 1970 Published by STARS, 1970 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 49 [1970], No. -

Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: the Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits

Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: The Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits by Anna Johns Hrom Department of History Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Supervisor ___________________________ Sarah Jane Deutsch ___________________________ Philip J. Stern ___________________________ Melissa B. Jacoby ___________________________ Benjamin Waterhouse Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Between Fraud Heaven and Tort Hell: The Business, Politics, and Law of Lawsuits By Anna Johns Hrom Department of History Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Supervisor ___________________________ Sarah Jane Deutsch ___________________________ Philip J. Stern ___________________________ Melissa B. Jacoby ___________________________ Benjamin Waterhouse An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Anna Johns Hrom 2018 Abstract In the 1970s, consumer advocates worried that Alabama’s weak regulatory structure around consumer fraud made it a kind of “con man’s heaven.” But by the 1990s, the battle cry of regulatory reformers had reversed, as businesspeople mourned the state’s decline into “tort hell.” Debates -

Historic News Volume 9, Issue 1 Spring-Summer 2004

Historic News Volume 9, Issue 1 Spring-Summer 2004 Enterprise-Ozark Community College Hosts AAH Annual Meeting held in Wiregrass Region The 2004 AAH Annual Meeting kicked off Friday, February 6 with sessions held at Enterprise-Ozark Community College. An intriguing his- tory of Fort Rucker presented by Judge Val McGee opened the ses- sions, followed by a discussion on Alabama’s contribution to the build- ing of the Panama Canal presented by George Lauderbaugh, Sarah Wiggins, and Linda York. Later that evening, the historic 1902 Rawls Hotel in downtown Enterprise provided the perfect backdrop for the Friday night banquet. Frye Gaillard, keynote speaker and author of Cradle of Freedom, related some of his own George Ewert discusses the controversy following his review of the personal experiences growing up in Civil War film, Gods and Generals. the South, as well as Alabama’s role representative, Susan DuBose gave an update in the national Civil on the state course of study in social studies. Rights movement. The annual business meeting was held during Saturday morning Saturday’s lunch and the new slate of officers attendees were treated elected. Our thanks go to Program Committee to a ‘super’ breakfast co-chairs Betty Brandon and David Carter and prepared to perfection to Local Arrangements Committee co-chairs by the local chapter of Jack Oden and Sam Covington for putting Phi Theta Kappa. The together this wonderful event. opening session in- cluded a discussion on Frye Gaillard the legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education decision by Lacy Ward (Tuskegee University) and Walter Gowan. -

A Tale of Two Alabamas

File: Hamill Macro Updated Created on: 5/22/2007 2:37 PM Last Printed: 5/22/2007 2:38 PM BOOK REVIEW A TALE OF TWO ALABAMAS Susan Pace Hamill* ALABAMA IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. By Wayne Flynt.** Awarded the 2004 Anne B. and James McMillan Prize. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 2004. Pp. 602. Illustrations. $39.95. * Professor of Law, University of Alabama School of Law. Professor Hamill gratefully acknowl- edges the support of the University of Alabama Law School Foundation, the Edward Brett Randolph Fund, the William H. Sadler Fund, and the staff at the Bounds Law Library, especially Penny Gibson, Creighton Miller, and Paul Pruitt, and also appreciates the hard work and insights from her “Alabama team” of research assistants, led by Kevin Garrison and assisted by Greg Foster and Will Walsh. I am especially pleased that this Book Review is appearing in the issue honoring my colleague Wythe Holt, whose example and support expanded for me the realm of what scholarship can be and do. ** Professor Emeritus, Auburn University; formerly Distinguished University Professor of History, Auburn University. Flynt is the author of eleven books, which have won numerous awards, including the Lillian Smith Book Award for nonfiction, the Clarence Cason Award for Nonfiction Writing, the Out- standing Academic Book from the American Library Association, the James F. Sulzby, Jr., Book Award (three times), and the Alabama Library Association Award for nonfiction (twice). His most important books include ALABAMA: THE HISTORY OF A DEEP SOUTH STATE (1994), a book he co-authored that is widely viewed as the finest single-volume history of an individual state and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, POOR BUT PROUD: ALABAMA’S POOR WHITES (1989), which also was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and DIXIE’S FORGOTTEN PEOPLE: THE SOUTH’S POOR WHITES (1979), which was reissued in 2004. -

Download Document

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Randy Sparks for being the most responsive dissertation advisor a graduate student could hope for, giving notes that consistently made this project better. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee, Emily Clark and Laura Rosanne Adderley, for their thoughtful feedback through this process. Thanks to funding from the School of Liberal Arts at Tulane University and the Episcopal Women’s History Project I had the opportunity to visit many archives throughout the South and meet quite a few helpful archivists and research librarians who made the experience even more rewarding. I also have the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation to thank for funding my final year of uninterrupted writing, for which I am eternally grateful. Finally, I would like to thank Ed for the emotional support and dedicate this work to all the active churchwomen in my family, especially Laura, Jackie, Lydia, Helen, and Jacqueline. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………...………ii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER 1……………………………………………………………………………..23 Preparing for Public Life in the Church: Religious Leadership and Benevolent Activism at Female Academies CHAPTER 2………………………………………………………………………..……78 Nurseries of Female Piety and Benevolence: The Gulf South’s Free and Enslaved Sunday Schools CHAPTER 3…………………………………………………………………………....142 “Her Piety Was a Living Oracle”: Public Speaking and Service in the Meetings of the Church CHAPTER 4……………………………………………………………………...…….215 Time, Talent, and -

2014 Newsletter

Volume XLIII Summer 2014 footnotes Wallace Named First Richard J. Stockham Jr. Chair of Western Intellectual History amford University's board of Wallace, who joined Samford’s trustees executive committee history faculty in 2002, specializes in S announced at its March 6 meeting religious and intellectual history and that Dr. William Jason Wallace will be researches the relationship between the first professor to hold the Richard J. religion and political thought. Stockham Jr. Chair of Western In addition to a number of articles Intellectual History. and review essays, he is the author of The chair is named in honor of Mr. Catholics, Slaveholders, and the Richard Stockham, Jr., a Birmingham Dilemma of American Evangelicalism, native and Princeton University graduate 1835-1860 (Notre Dame, 2010). His who cared deeply about the educational latest book, Collapse of the Covenant: value of the Western and Christian The Transformation of the Puritan Ideal, intellectual traditions. is forthcoming from The Johns Hopkins As outlined by the board, the holder University Press. of the Stockham Chair provides Among his other professional SAMFORD UNIVERSITY administrative oversight of the honors, Wallace earned the 2011 Howard university's Core Texts Program. For College of Arts and Sciences Outstanding Wallace, these duties include managing Teacher award. the Cultural Perspectives (UCCP) curriculum, defining the needs of the curriculum, and assessing and revising the program as needed. Fulbright Grant Awarded to History Graduate for Second Consecutive Year or the Brown said Samford history given me a great opportunity, and I hope second professor Jim Brown’s Modern Russia to make good on it in the future,” Brown F time in course sparked his interest in the central said. -

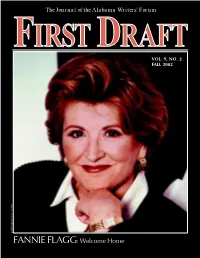

Vol.9, No.2 / Fall 2002

The Journal of the Alabama Writers’ Forum NAME OF ARTICLE 1 FIRST DRAFT VOL. 9, NO. 2 FALL 2002 COPYRIGHT SUZE LANIER FANNIE FLAGG: Welcome Home 2NAME OF ARTICLE? From the Editor FY 02 The Alabama Writer’s Forum BOARD OF DIRECTORS President PETER HUGGINS Auburn Vice-President BETTYE FORBUS Dothan Secretary LINDA HENRY DEAN Auburn First Draft Welcomes Treasurer New Editors Jay Lamar FAIRLEY MCDONALD Montgomery Writers’ Representative We are pleased to announce two new book review editors for the coming AILEEN HENDERSON Brookwood year. Jennifer Horne will be Poetry editor, and Derryn Moten will serve as Ala- Writers’ Representative bama and Southern History editor. Horne’s publications include a chapbook, DARYL BROWN Florence Miss Betty’s School of Dance (bluestocking press, 1997), and poems in Ama- JULIE FRIEDMAN ryllis, Astarte, the Birmingham Poetry Review, Blue Pitcher (poetry prize Fairhope 1992), and Carolina Quarterly, among other journals. An MFA graduate of the STUART FLYNN Birmingham University of Alabama, Horne has taught college English, been an artist in ED GEORGE residence, and served as a journal, magazine, and book editor. She is currently Montgomery pursuing a master’s in community counseling. JOHN HAFNER Mobile Moten is associate professor of Humanities at WILLIAM E. HICKS Alabama State University and holds a Ph.D. and Troy RICK JOURNEY an MA in American Studies from the University Birmingham of Iowa, as well as an MS in Library Science DERRYN MOTEN Montgomery from Catholic University of America. Recent DON NOBLE publications include “When the ‘Past Is Not Tuscaloosa Even the Past’: The Rhetoric of a Southern His- STEVE SEWELL Birmingham torical Marker” (Professing Rhetoric, Lawrence PHILIP SHIRLEY Erlbaum Associates, 2002) as well as “To Live Jackson, Mississippi Derryn Moten and Die in Dixie: Alabama and the Electric LEE TAYLOR Monroeville Chair” (Alabama Heritage, 2001). -

Baptists and Race in the American South1

84 Journal of European Baptist Studies 19:2 (2019) Baptists and Race in the American South1 Kenneth B. E. Roxburgh The essay explores the attitude of Baptists in the American South towards race, indicating that the issue is long lasting. It includes a survey of racism in the early nineteenth century, culminating in the civil war, but extending to the Jim Crow era and the more recent expressions of white supremacy. Special attention is paid to the formation and development of the Southern Baptist Convention, and the ‘repentance’ of the Convention at the 1995 Southern Baptist Convention with respect to its origins in 1845 over the issue of slavery. The article also examines the way in which integration at Samford University, a Baptist school in Alabama, illustrates the struggle for equality between the races. Keywords Race; slavery; Jim Crow era; white supremacy; racial reconciliation Introduction Baptist life in the American South has a long and troubled history, marked by remarkable growth and yet facing various issues of discerning the will of God, especially in regard to race. Up until the Revolutionary War in 1776, significant westward expansion had been halted at the Appalachian Mountains. Following the Revolution there was a sense of national identity, optimism, and hope. The economy was strong and the population was growing. The Louisiana purchase of 1803 would double the size of the country, as over 900,000 square miles were purchased for fifteen million dollars. The territory was carved into thirteen states, or parts of states, and put the United States in a position to become a world power. -

Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing Religious Identity: Southern Baptists and Anti-Catholicism, 1870-1920 by David Terrell Mitchell A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 8, 2012 Copyright 2012 by David Terrell Mitchell Approved by J. Wayne Flynt, Chair, Distinguished University Professor of History, Emeritus Charles Israel, Associate Professor of History David Carter, Associate Professor of History Richard Penaskovic, Professor of Religious Studies Abstract This dissertation examines how Southern Baptists utilized anti-Catholicism to reconstruct their religious identity from 1870 to 1920. It documents the beliefs, rhetoric, and actions of Baptists as they encountered Catholics both at home and abroad. It is the first manuscript detailing Southern Baptist perceptions of Catholics and Catholicism from the Reconstruction to the end of World War I. It offers a new point of departure for southern religious history by examining how the South’s largest denomination responded to and was shaped by a non-Protestant religious group. ii Acknowledgments There are so many people that deserve recognition. Archivist Laura Botts at Mercer University’s Georgia Baptist History Depository, Lisa Persinger at Wake Forrest Unversity’s North Carolina Historical Collection, and Gillian Brown at the Roman Catholic Diocese of Savannah all generously shared their resources and ideas with me. Bill Sumners and Taffey Hall made my research at the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives a pleasant and productive experience. Committee members Charles Israel, David Carter, and Richard Penaskovic offered useful comments. For his meticulous editing, constructive criticism, and generosity with his time, I am grateful to my director, Wayne Flynt.