Making the Case for New Zealand Reds by REBECCA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

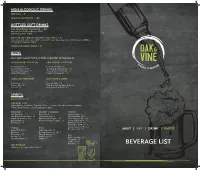

Beverage List

NON ALCOHOLIC DRINKS RED BULL | 5 LEMON LIME BETTERS | 4.5 BOTTLED SOFT DRINKS SAN PELLEGRINO SPARKLING | 5.5 Aranciata Rossa (Blood Orange) 330ml Limonata (Lemon) 330ml BOTTLED SOFT DRINKS AND BOTTLED JUICES | 5 Coca cola, Sprite, Coke Zero, Orange Juice,Pineapple Juice, Apple Juice, Bottlled water (400ml), Bottled sparkling water (250ml) SPARKLING WATER 750ML | 8 BEERS Ask your waiter for our wide selection of tap beers. IMPORTED BOTTLED BEERS CRAFTED BOTTLED BEERS Kirin (Japan) | 9.5 Lazy Yak Pale Ale | 10 Corona (Mexico) | 8.5 Mountain Goat Steam Ale | 10 Heineken (Germany) | 9.5 Stone & Wood Pacific Ale | 10 Singha (Thailand) | 8 Furphy Refreshing Ale | 9.5 LOCAL BOTTLED BEERS LIGHT BEER & CIDER Carlton Dry | 8 Cascade light | 7.5 Crown Lager | 8 Dirty Granny Craft Apple Cider | 9 Iron Jack | 8 Strongbow Pear Cider | 5.5 SPIRITS BAISC SPIRITS | 8 LIQUEURS | 9.5 Midori, Kahlua, Frangelico, Cointreau, Baileys, Tia Maria, Drambuie, Galiano sambuca (White, Black, Vanilla), Sierra Tequilla (silver, gold) BOURBON BRANDY & COGNAC WHISKY Jack Daniel No. 7 | 9 Remy Brandy | 8 Jameson Irish | 9 Jack Daniel Single barrel | 12 St Agnes Brandy | 9 Canadian Club | 8.5 Sounthern Comfort | 8.5 Hennessey Vs Cognac | 10 Chivas Regal 12YR | 10 Makers Mark | 9 Courvoisier Vsop Congnac | 13 Chivas Regal 18YR | 15 Wild Turkey | 10 Dilwhinnie 15YR | 13 Glenfiddich 12YR | 11.5 Glenmorangie 10YR | 12 VODKA RUM Bowmore Islay | 14 Smirnoff Red | 8.5 Hvana Especial | 10 MEET | EAT | DRINK | ENJOY Belvedere | 11 Captain Morgan Spiced | 9 Grey Goose | 14 Bacardi -

Managing Grapevine Trunk Diseases (Petri Disease, Esca, and Others) That Threaten the Sustainability of Australian Viticulture

MANAGING GRAPEVINE TRUNK DISEASES (PETRI DISEASE, ESCA, AND OTHERS) THAT THREATEN THE SUSTAINABILITY OF AUSTRALIAN VITICULTURE Petri disease esca FINAL REPORT to GRAPE AND WINE RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Project Number: CRCV 2.2.1 Principal Investigator: Dr Jacqueline Edwards Research Organisation: Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture Date: 31 August 2006 Project Title: Managing grapevine trunk diseases (Petri disease, esca, and others) that threaten the sustainability of Australian viticulture CRCV Project Number: 2.2.1 Period Report Covers: July 1999 – June 2006 Author Details: Dr Jacqueline Edwards Department of Primary Industries, Victoria Private Bag 15, DPI Knoxfield Centre, Ferntree Gully DC, Victoria 3156 Phone: (03) 9210 9222 Fax: (03) 9800 3521 Mobile: 0417360946 Email: [email protected] Date report completed: August, 2006 Publisher: Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture ISBN OR ISSN: Copyright: ã Copyright in the content of this guide is owned by the Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture. Disclaimer: The information contained in this report is a guide only. It is not intended to be comprehensive, nor does it constitute advice. The Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture accepts no responsibility for the consequences of the use of this information. You should seek expert advice in order to determine whether application of any of the information provided in this guide would be useful in your circumstances. The Cooperative Research Centre for Viticulture is a joint venture between the following core participants, working with a wide range of supporting participants. CRCV2.2.1 Managing grapevine trunk diseases TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 3 Executive Summary 4 Background 7 Project aims and performance targets 9 Chapter 1. -

New Zealand Winegrowers Annual Report

NEW ZEALAND WINEGROWERS INC Annual Report 2020 200 Years Celebration Te Whare Ru¯nanga, Waitangi WITHER HILLS Vision Around the world, New Zealand is renowned for our exceptional wines. Mission To create enduring value for our members. Purpose To protect and enhance the reputation of New Zealand wine. To support the sustainable diversified value growth of New Zealand wine. Activities Advocacy, Research, Marketing, Environment COVER PHOTO: NZW 200 YEARS CELEBRATION, TE WHARE RUNANGA, WAITANGI NEW ZEALAND WINEGROWERS INC Annual Report 2020 Chair’s Report 02 Advocacy 06 Research 12 Sustainability 16 Marketing 20 Financials 29 Statistics 32 Directory 40 Chair’s Report NZW 200 YEARS CELEBRATION Perhaps more than any other year in recent times, this was a year of two halves. During the first half of the year the thriving New Zealand wine industry In New Zealand, we were privileged industry celebrated its past, and where - every second of everyday - to be able to complete our grape looked ahead with optimism. The 80 glasses of its distinctive wine are harvest as “essential businesses”, but second half reminded us just how sold somewhere in the world. the effort and stress involved in doing unpredictable the world can be, how so safely was high. Our total 2020 crucial it is to plan for the unexpected, A milestone was reached in February, harvest of 457,000 tonnes reflects and react with agility when the with the opening of the Bragato the near perfect growing conditions unexpected arrives. Research Institute’s Research Winery. experienced in most of the country, This new facility provides us a base and a 2% increase in planted area In September we celebrated the from which to set the national to 39,935 hectares. -

Pinot Noir Appellation

Cobblestone Vineyards From his humble beginnings on a Michigan farm, Saul Levine became an FM radio pioneer in 1959 launching Mt. Wilson FM Broadcasters in Southern California. Levine’s radio success helped him get back to his roots, and with his wife Anita he started Cobblestone Vineyards. For over 30 years Cobblestone only grew grapes for premium California wineries, until 2004 when the Levines released their own wines under the Cobblestone label. The First Cobblestone estate began in 1972, in Monterey County. This Vineyard has grown to 50 acres and is planted to Chardonnay. In 1997, they purchased 25 acres high in the slopes of Atlas Peak North East of the town of Napa. This Vineyard led to their very first commercial release of Cabernet Sauvignon in 2001. Their recent purchased of a exceptional property along Te Mina Road, an especially remarkable terrace in the celebrated Pinot Noir village of Martinborough, New Zealand. The Wines 2009 Pinot Noir Te Muna Martinborough, New Zealand HK$290/Btl "Cobblestone's Pinot Noir Named New Zealand's NO.1 wine" - TIZ.COM press release. With the new purchased Pinot Noir vineyard and it's debut, Cobblestone vineyard has been awarded the highly coveted trophies for both champion Pinot Noir as well as overall champion wine of the show at the 2010 Romeo Bragato wine award in New Zealand. Showcasing true Burgundian character, Bragato Trophy – Champion Wine – Romeo Bragato Wine Awards Mike Wolter Memorial Trophy – Champion Pinot Noir – Romeo Bragato Wine Awards Gold Medal – Romeo Bragato Wine Awards – NZ Winegrowers The 2009 Cobblestone Te Muna Pinot Noir delivers outstanding elegance, balance and complexity. -

Romeo Alessandro Bragato 1858

ROMEO ALESSANDRO BRAGATO 1858 - 1913 ‘THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HIS WORK TO NEW ZEALAND’ THE EARLY YEARS Romeo Bragato was born in 1858 on the Adriatic island of Lussin Piccolo, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (now known as Mali Losinj – part of Croatia). His father was Giuseppe and his mother Paolina Depangher was from Vienna. The family may have been involved in salt extraction from sea water. Romeo was the eldest of a family of five children. His two brothers were Massimiliano (Max) and Giulio and his sisters were Marietta and Annelie. The two girls spent some of their school years in Lausanne, Switzerland. Romeo’s early schooling was at Pirano on the Istrian peninsular about 30 kms south of Trieste. He first trained as an architect in Vienna and then he attended the Regia Scuola di Viticoltura ed Enologia in Conegliano between 1879 & 1883. Conegliano is in the heart of the Veneto wine growing region. In his last year at Conegliano he gave two addresses, the first on 7 January 1883 on the previous harvest on the islands of Quarnaro & Dalmazia, and the second on 11 February 1884,discussed his findings on crop rotation. Bragato graduated in 1883 with the Diploma R.S.S.V.OE and returned to Lussin Piccolo where he was oenologist at the Istrian Association of Agriculture and later viticulturist and cellarmaster for the Gerolimiche brothers. AUSTRALIA Bragato travelled to Melbourne Australia in 1888 where he became Viticulturist to the Victorian Department of Agriculture. In 1889 he published a report on the potential for viticulture in the State of Victoria. -

The Book of New Zealand Wine NZWG

NEW ZEALAND WINE Resource Booklet nzwine.com 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 100% COMMITTED TO EXCELLENCE Tucked away in a remote corner of the globe is a place of glorious unspoiled landscapes, exotic flora and fauna, and SECTION 1: OVERVIEW 1 a culture renowned for its spirit of youthful innovation. History of Winemaking 1 New Zealand is a world of pure discovery, and nothing History of Winemaking Timeline 2 distills its essence more perfectly than a glass of New Zealand wine. Wine Production & Exports 3 New Zealand’s wine producing history extends back to Sustainability Policy 4 the founding of the nation in the 1800’s. But it was the New Zealand Wine Labelling Laws introduction to Marlborough’s astonishing Sauvignon & Export Certification 5 Blanc in the 1980’s that saw New Zealand wine receive Wine Closures 5 high acclaim and international recognition. And while Marlborough retains its status as one of the SECTION 2: REGIONS 6 world’s foremost wine producing regions, the quality of Wine Regions of New Zealand Map 7 wines from elsewhere in the country has also achieved Auckland & Northland 8 international acclaim. Waikato/ Bay of Plenty 10 Our commitment to quality has won New Zealand its reputation for premium wine. Gisborne 12 Hawke’s Bay 14 Wairarapa 16 We hope you find the materials of value to your personal and professional development. Nelson 18 Marlborough 20 Canterbury & Waipara Valley 22 Central Otago 24 RESOURCES AVAILABLE SECTION 3: WINES 26 NEW ZEALAND WINE RESOURCES Sauvignon Blanc 28 New Zealand Wine DVD Riesling 30 New Zealand Wine -

Overview of NZ Viticulture & Aquaculture

An Overview of New Zealand’s Viticultural and Aquaculture Industries August 2016 Dr Debbie Care Research Leader - Primary Industries Transdisciplinary Research and Innovation Waikato Institute of Technology Private Bag 3036, Waikato Mail Centre, Hamilton 3240 e - [email protected] p - 027 242 0586 www wintec ac nz Overview of the Viticulture & Aquaculture Industries in NZ 1 of 29 Overview............................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 History .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Major Producing Regions ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Statistical Overview .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Recent Production Figures ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Trade - Exports ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Chinese Market -

Arming Against Frost

Wine Australia for Australian Wine Factsheet September 2010 Arming against frost Joanna Jones, Tasmanian Institute of Agricultural Research (TIA); Steve Wilson, Consultant Introduction or creating larger scale valley flows of freezing air. This fact sheet is designed to give some directions These topographic influences are characteristic of a and assistance in dealing with the, often confusing, region, change little from frost to frost and are often information and advice available both before and enshrined in local folklore. Frost ‘pockets’ are reasonably after a serious frost event. It is not intended to provide predictable, are usually well known to local residents the technical detail required to make a significant and site selection to avoid them is the first and most investment in any particular site or frost protection basic step in frost management. Flows of cold air are system. Looking to the future, although climate change a little less constant from frost to frost and moving models suggest reduced spring frost frequency in all air tends to more turbulent with a smaller change in regions, the danger is unlikely to diminish as warmer temperature with elevation compared with still air winter temperatures lead to earlier spring bud burst. collected in a frost pocket. Furthermore, in some regions climate change may lead to the advent of more clear sky spring days coupled with drier soils increasing the incidence and severity of frosts. Paradoxically the warmest decade in recorded history has seen some of the most widespread and serious frost damage to commercial crops in both Australia and North America. Frost and climate Southern Australia is not prone to the disastrous large- scale freeze events that occasionally occur in North America and parts of Europe. -

NZ Winegrowers Annual Report 2019

NEW ZEALAND WINEGROWERS INC ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Vision Around the world, New Zealand is renowned for our exceptional wines. Mission To create enduring value for our members. Purpose To protect and enhance the reputation of New Zealand wine. To support the sustainable diversified value growth of New Zealand wine. Activities Advocacy, Research, Marketing, Environment New Zealand Winegrowers Inc Annual Report 2019 01 Chair’s Report 02 02 Advocacy 10 03 Research 16 04 Sustainability 24 05 Marketing and Events 28 06 Information Resources 42 07 Financials 44 08 Statistics 46 09 Directory 54 1 01 CHAIR’S REPORT This year the Board Evolving for the Future completed its strategic The strategic review report concludes review of the wine that our focus as an industry needs to be on enhancing the industry’s industry — its first since reputation and sustainability 2011. We engaged credentials, responding to changing Pricewaterhouse Coopers market dynamics, and managing and to help us dig deep into a mitigating risks to profitability, all underpinned by maintaining quality, wide range of questions. distinctive wine styles. The process, and their So what have we done as a result report, provided us of the review? and all members with a First, it’s your review, so we shared wealth of usable insights it with you. We visited all the main into the state of our wine regions in October to present sector, challenges and the report and its finding to members, opportunities. and again last month we toured the regions to explain decisions taken so far, and how it will be implemented. -

Industry Partnerships Programme the Australian Wine Grape Industry

Industry Partnerships Programme The Australian Wine Grape Industry Taking Stock and Setting Directions Final Report, December 2006 Prepared by THE AUSTRALIAN WINE GRAPE INDUSTRY TAKING STOCK AND SETTING DIRECTIONS PROJECT, 2006 ABOUT KIRI-GANAI RESEARCH Kiri-ganai Research Pty Ltd is a Canberra based consultancy company that undertakes consultancy and analytical studies concerned with industry performance, natural resource management and sustainable agriculture. Our strength is in turning knowledge gained from markets, business operations, science, research and policy into ideas, options, strategies and business plans for industries and businesses. Kiri-ganai Research Pty Ltd GPO Box 103 CANBERRA ACT 2601 AUSTRALIA ph: +62 2 62956300 fax: +61 2 62327727 www.kiri-ganai.com.au Project team The project was led by Kiri-ganai Research Pty Ltd under the direction of Dr Richard Price, Managing Director. Ken Moore and Richard were the team s analysts, with Ken being the principal author of the report. Michael Williams of Mike Williams & Associates Pty Ltd facilitated the two industry workshops in August and November 2006. Acknowledgements The many wine grape growers, winemakers and other industry stakeholders who gave their valuable time, insights and knowledge during meetings with the consultants and in the industry workshops. The Project Management Committee comprising Alan Newton, Mark McKenzie, Michael Matthews, Mike Stone, Brian Simpson, Roseanne Healy, Kerrin Smart, Guy Adams, Bob Taplin, Bill Schumann and Fiona Hill, The authors of many reports reviewed by the Project Team whose information, knowledge and insights are acknowledged and greatly respected in building a complete picture of the Australian wine grape industry. Structure of this report This report is set out in two parts: Part A is the summary of the project, the project findings and conclusions, and the results of Setting Directions for the future of the Australian wine grape industry. -

'White Shiraz' in New South Wales: the History and Mystery

‘White Shiraz’ in New South Wales: The History and Mystery of the Hunter Valley’s Trebbiano Plantings, Their Source, and Their Misidentification Author: Dr. Gerald Atkinson, grapevine researcher and historian. — Copyright (©) Gerald Atkinson, 2020. Introduction: What’s In A Name? In their recently published book Hunter Wine: A History1, Julie McIntyre and John Germov make the remarkable revelation that “Shiraz” (i.e. Syrah) which they explicate as the “French grape known too” in colonial Australia “as Red Hermitage” was “donated to the Botanic Gardens” in Sydney “by … Governor Brisbane”2. A little earlier in their book an image of a manuscript which appears to support this claim is printed. The relevant excerpted portion of it is this, with the ‘Shiraz’ entry on the immediate left: The source of this image is a handwritten catalogue in which all of the kinds and varieties of plants held in the colonial Sydney Botanic Gardens as of November 1827 are listed3. As Lionel Gilbert has noted, this catalogue had its origins in December 1825, [when Lord] Bathurst [Secretary of State for the Colonies] requested half-yearly reports on the Gardens, [of which] the first [of these was] to include “an accurate description of the Plants and Vegetables, which are peculiar to the climate of New South Wales, as well as those, peculiar to other Countries, which are susceptible of cultivation to any useful purpose, if introduced to the Colony.” Governor Darling responded by sending a report based on lists of ‘Fruits’ and ‘Exotic Forest Trees cultivated in the Botanic Garden’ compiled late in 1827. -

AWRI Annual Report 2003

The Australian Wine Research Institute Annual Report 2003 2003 DIRECTOR’S REPORT 2 Council Members The Company Mr R.E. Day, BAgSc, BAppSc Chairman The Australian Wine Research Institute was incorporated under the South Australian Elected a member under Clause 6(e) of Companies Act on 27 April 1955. It is a company limited by guarantee, it does not the Articles of Association have a share capital and it has been permitted, under licence, to omit the word ‘limited’ from its registered name. The Constitution of The Australian Wine Research Mr J.F. Brayne, BAppSc(Oen) Institute sets out in broad terms the aims of the Institute and the Report of the Elected a member under Clause 6(e) of Committee of Review for the Institute published in March 1977 identified the the Articles of Association following specific aims: Mr P.J. Dawson, BSc, BAppSc(Wine Science) 1. To carry out applied research in the field of oenology. Elected a member under Clause 6(e) of 2. To service the extension needs of the winemakers of Australia. the Articles of Association 3. To be involved in the teaching of oenology at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Mr P.F. Hayes, BSc, BAppSc, MSc, DipEd 4. To assume responsibility for the co-ordination of oenological activities, and the Elected a member under Clause 6(e) of collection, collation and dissemination of information on oenological and the Articles of Association viticultural research to the benefit of the Australian wine industry. Professor P.B. Høj, MSc, PhD The Institute’s laboratories and offices are located within an internationally renown Ex officio under Clause 6(d) of the research cluster on the Waite Precinct at Urrbrae in the Adelaide foothills, on land Articles of Association as Director of leased from the University.