Adam Potts PASSIVE NOISE Abstract This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iggy & the Stooges

3/29/2011 Iggy & the Stooges - "Raw Power Live:… Share Report Abuse Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In Ads by Google Band Iggy Pop Video DVD Disc Disc Jockey Music SATURDAY, MARCH 05, 2011 HELP PUT CHICAGO'S EMPIRES ON THE COVER OF ROLLING STONE Iggy & the Stooges - "Raw Power Live: In the Hands of the Fans" CD Review (MVD) RollingStone Do you wanna be a Rock & Roll Star? Presented by Garnier Fructis On Friday, Sept. 3rd last year, Iggy & the Stooges (featuring James Williamson on guitar) performed Help put 197 3's Raw Power in its entirety at All Empires Tomorrow's Parties New York. A live document of on the cover of this show, Raw Power Live: In the Hands of the Fans , is coming out next month as a limited edition 180 gram vinyl release for Record Store Day 2011. "Getting this top-notch performance of the entire Raw Power album by The Stooges realized a life long dream, " said Iggy Pop " This shit really sizzles RATE THIS and we are so obviously a crack band in a class 1 of our own. " 2 3 4 5 BrooklynRocks Concert Calendar Today Tuesday, March 29 Thursday, March 31 8:00pm Bridge to Japan (Benefit Concert) Saturday, April 2 8:00pm Tommy Rodgers (BTBAM) Saturday, April 9 10:00pm Surf City / Bardo Pond Monday, April 11 9:00pm The Builders and The Butchers Tuesday, April 12 9:00pm Surf City Thursday, April 28 Events show n in time zone: Eastern Time CONTACT INFO. Billboard Magazine had the following to say about The Stooges' performance: " [a]s the pretty clear M IKE main attraction, Iggy and the Stooges granted a predictably explosive show. -

Bio Information: RICHARD PINHAS Title: METAL/CRYSTAL (Cuneiform Rune 308/309)

Bio information: RICHARD PINHAS Title: METAL/CRYSTAL (Cuneiform Rune 308/309) Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) http://www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: ROCK / ELECTRONIC / NOISE RICHARD PINHAS “Richard Pinhas is still a force in world music today…his music has the emotive depth that most other electronauts hardly begin to grapple with. Add to this its other attributes: alien atmospheres, futuristic imagery, feelings of the mystery of technology, precise clinical production, belief in creative and political revolution, an obscure intellectual base and references to science fiction…then there is a musical force that has little or no rival.” – Audion “Richard Pinhas,…the astonishingly talented French pioneer…it’s no exaggeration to state he’s managed to cross the philosophies of J.G Ballard and Jean Giraud with the guitar sound of Robert Fripp, and thereby arrived at a cosmos-shattering glimps into the infinite.” – The Sound Projector MERZBOW "Think of those artists who overpowered the grind of their eras: Bach, Wagner, Miles Davis, The Beatles -- all of these people were consistently displaced of their time by the striking originality of their work, and yet were quintessentially "then". This is rare, indeed, and there is a case for including Masami Akita (a.k.a. Merzbow) in such a group. On the one hand, he is merely the brightest fire in an eclectic, almost anarchic Japanese music scene. On the other, Merzbow's music shatters scenes and precedents. Masami Akita is his own context, and listeners enter that world at their own risk." – Pitchfork WOLF EYES “If Deleuze had made it past '95, he might have written about [Wolf Eyes CD]. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Hathawayinterview

MARCH 2019 #96 Real estate: Cashflow is king Luxury: Las Vegas! Fitness Group exercise Design Decor legends Travel Pita Maha, Bali Ardennes-Etape Radisson Red Champagne & Dining PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT Listen to your body Technology in Africa Transforming the mind Money & Politics Arnon Barnes: Giving back The three-letter word Be successful books Fashion & Beauty Art attitude Anne WWW.TOGETHERMAG.EU HathawayInterview IN A CHANGING WORLD, EXPATS FEEL AT HOME RIGHT AWAY. WITH YOU FROM THE START Simply enjoy the Belgian way of life. We take care of all your banking & BE 403.199.702 3 - B 1000 Brussels RPM/RPR Brussels, VAT Montagne du Parc/Warandeberg SA/NV, Fortis BNP Paribas Publisher: E. Jacqueroux, insurance matters. More info on bnpparibasfortis.be/expatinbelgium. The bank for a changing world BNP-11046-038892473327 - Nouvelles affiches agences EXPATS_330x230.indd 1 06/06/2018 14:45 YOUR SCAPA & SCAPA HOME LIFESTYLE STORE BOULEVARD DE WATERLOO 26 +32 2 469 02 77 BRUSSELS / BRUXELLES / BRUSSEL Editor’s IMAGINE THERE’S LETTER A HEAVEN A friend of mine was reading a book with an intriguing title, or rather she was re-reading it even though she had promised to pass it on to a niece – she couldn’t resist delving back into it one more time. It was written by Jason Leen or rather by John Lennon himself several years after his death. What’s that you say? Yes, af ter… The aforementioned intriguing title is: Peace at Together: Last: The After-Death Experiences of John Inspiring you Lennon, published in 1998. Leen describes his to reach your dreams.. -

Freeandfreak Ysince

FREEANDFREAKYSINCE | DECEMBER THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | DECEMBER | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR - YEARINREVIEW 20 TheInternetTheyearofTikTok theWorldoff erstidylessonson “bootgaze”crewtheKeenerFamily @ 04 TheReaderThestoryof 21 DanceInayearoflosswefound Americanpowerdynamicsand returnwithasecondEP astoldthroughsomeofourfavorite thatdanceiseverywhere WildMountainThymefeaturesone PPTB covers 22 TheaterChicagotheaterartists ofthemostagonizingcourtshipsin OPINION PECKH 06 FoodChicagorestaurantsate rosetochallengesandcreated moviehistory 40 NationalPoliticsWhen ECS K CLR H shitthisyearAlotofshitwasstill newonesin politiciansselloutwealllose GD AH prettygreat 24 MoviesRelivetheyearinfi lm MUSIC &NIGHTLIFE 42 SavageLoveDanSavage MEP M 08 Joravsky|PoliticsIthinkwe withthesedoublefeatures 34 ChicagoansofNoteDoug answersquestionsaboutmonsters TDEKR CEBW canallagreethenextyearhasgot 28 AlbumsThebestoverlooked Maloneownerandleadengineer inbedandmothersinlaw AEJL tobebetter Chicagorecordsof JamdekRecordingStudio SWMD LG 10 NewsOntheviolencesadness 30 GigPostersTheReadergot 35 RecordsofNoteApandemic DI BJ MS CLASSIFIEDS EAS N L andhopeof creativetofi ndwaystokeep can’tstopthemusicandthisweek 43 Jobs PM KW 14 Isaacs|CultureSheearned upli ingChicagoartistsin theReaderreviewscurrentreleases 43 Apartments&Spaces L CSC-J thetitlestillhewasdissingher! 32 MusiciansThemusicscene byDJEarltheMiyumiProject 43 Marketplace SJR F AM R WouldhedothesametosayDr doubleddownonmutualaidand FreddieOldSoulMarkLanegan CEBN B Kissinger? fundraisingforcommunitygroups -

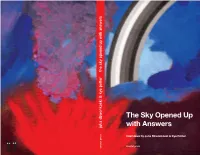

The Sky Opened up with Answers

The Sky Opened Up with Answers julia dzwonkoski & kye potter the sky opened up with answers Interviews by Julia Dzwonkoski & Kye Potter onestar press onestar press DZWONKOSKI_COVER.indd 1 23/03/09 13:57:50 The Sky Opened Up with Answers Interviews by Julia Dzwonkoski & Kye Potter RICHARD WICKA / Te Home of the Future 5 ANIMAL CHARM / Bacon, Eggs and Sweet Mary Jane 23 WYNN SATTERLEE / Painting and Prison 37 NAOMI UMAN / Te Ukrainian Time Machine 47 CHARLIE NOTHING / 180 Needles into Sonny Rollins 61 ERNEST GUSELLA / I’m Not a Believer 71 BRIAN SPRINGER / Te Disappointment 85 HENRY FLYNT / Te Answer You Like is the Wrong Answer 99 TWIG HARPER & CARLY PTAK / Livin’ & Feelin’ It 115 THEO KAMECKE / Trow the House in the River 133 DZWONKOSKI_INT_150.indd 2-3 6/04/09 10:26:36 Te Home of the Future An Interview with Richard Wicka Buffalo, New York, August 1, 2007 Richard Wicka has been producing public access television shows at his Buffalo, New York home, Te Home of the Future, for over 20 years. Hundreds of people have visited the HOTF to work on TV shows, film shoots and radio programs. We talked with Wicka about the history of the HOTF and the social and artistic vision behind it. JULIA DZWONKOSKI & KYE POTTER: Can you tell us the story of the pond in your backyard? RICHARD WICKA: I went to nurseries and said: “How do you put a pond in your backyard?” Tey all told me the same thing: “You’ve gotta dig a hole at least three feet deep.” Why? “Because water freezes in the win- ter but never to a depth of three feet. -

1989 and After

1 1989 AND AFTER BEGINNINGS It begins with a string quartet: two violins, a viola, and a cello pumping notes up and down like pistons. An image of the American machine age, hallucinated through the sound of the European Enlightenment. Th e image is strengthened as a voice—mature, female, American—intones an itinerary: “From Chicago . to New York.” Th e sound is prerecorded, digitally sampled and amplifi ed through speakers beside the ensemble. More samples are added: more voices; the whistles and bells of trains; one, two, three, or even more string quartets. Rapidly the musi- cal space far exceeds what we see on stage. Th is is a string quartet for the media age, as much recordings and amplifi cation as it is the four musicians in front of us. Yet everything extends from it and back into it, whether the quartet of quartets, which mirror and echo each other; the voices, which seem to blend seamlessly with the instrumental rhythms and melodies; or the whistles, which mesh so clearly with the harmonic changes that it seems certain they come from an unseen wind instrument and not a concrete recording. ••• It begins with thumping and hammering, small clusters struck on the piano key- board with the side of the palm or with three fi ngers pressed together, jabbing like a beak. Th e sound recalls a malevolent dinosaur or perhaps a furious child, but it isn’t random; a melody of sorts, or an identifi able series of pitches at least, hangs over the tumult. Aft er twenty seconds or so the thunder halts abruptly for a two- note rising motif played by the right hand, which is then imitated (slightly altered) 1 2 1989 AND AFTER by the left . -

Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, the Haters, Hanatarash, the Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese…

As Loud as Possible As Loud as Possible Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… Un parcours parmi les grandes figures du harsh noise, au sein de l’internationale du bruit sale de ses origines à nos jours. AS LOUD AS 48 POSSi- 49 bLe. Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… A tour among the major figures in harsh noise, within dirty Noise International—from its inception to the present day. Fenêtre ouverte. Le bruit, c’est ce son fronde, indompta- juste une main pour sculpter, une intention pour guider, Mais comment la musique a-t-elle osé muter en ça ? ble, discordant, une puanteur dans l’oreille, comme l’a écrit à peine une idée pour le conceptualiser. Il n’est pas une Objectivement, si on regarde la tête du harsh noise, son Ambrose Bierce dans son Devil’s Dictionary, ce que tout musique bruyante mais une musique-bruit taillée, pas un nom, il faut tout de même se pencher un peu en arrière, le oppose et tout interdit à la musique. Le bruit sévère, le bruit genre, encore moins un mélange, car s’il est né d’amonts XXe siècle brouhaha, pour comprendre cette « birth-death dur, le harsh noise, c’est, pire encore, le chaos volontaire, la lisibles dans l’histoire de la musique, dans l’histoire du XXe experience », si l’on m’autorise à citer le titre d’un disque de crasse en liberté, même pas la musique de son-bruits rêvée siècle, il n’a dans sa pratique et sa nature d’autre horizon Whitehouse, le premier de surcroît. -

Alternate African Reality. Electronic, Electroacoustic and Experimental Music from Africa and the Diaspora

Alternate African Reality, cover for the digital release by Cedrik Fermont, 2020. Alternate African Reality. Electronic, electroacoustic and experimental music from Africa and the diaspora. Introduction and critique. "Always use the word ‘Africa’ or ‘Darkness’ or ‘Safari’ in your title. Subtitles may include the words ‘Zanzibar’, ‘Masai’, ‘Zulu’, ‘Zambezi’, ‘Congo’, ‘Nile’, ‘Big’, ‘Sky’, ‘Shadow’, ‘Drum’, ‘Sun’ or ‘Bygone’. Also useful are words such as ‘Guerrillas’, ‘Timeless’, ‘Primordial’ and ‘Tribal’. Note that ‘People’ means Africans who are not black, while ‘The People’ means black Africans. Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book, or in it, unless that African has won the Nobel Prize. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these. If you must include an African, make sure you get one in Masai or Zulu or Dogon dress." – Binyavanga Wainaina (1971-2019). © Binyavanga Wainaina, 2005. Originally published in Granta 92, 2005. Photo taken in the streets of Maputo, Mozambique by Cedrik Fermont, 2018. "Africa – the dark continent of the tyrants, the beautiful girls, the bizarre rituals, the tropical fruits, the pygmies, the guns, the mercenaries, the tribal wars, the unusual diseases, the abject poverty, the sumptuous riches, the widespread executions, the praetorian colonialists, the exotic wildlife - and the music." (extract from the booklet of Extreme Music from Africa (Susan Lawly, 1997). Whether intended as prank, provocation or patronisation or, who knows, all of these at once, producer William Bennett's fake African compilation Extreme Music from Africa perfectly fits the African clichés that Binyavanga Wainaina described in his essay How To Write About Africa : the concept, the cover, the lame references, the stereotypical drawing made by Trevor Brown.. -

Merzbow, Mats Gustafsson, Balazs Pandi –

Merzbow, Mats Gustafsson, Balazs Pandi – Cuts Open (85:42, DCD, DLP-Vinyl, Digital, RareNoiseRecords, 2020) Wenn die Namen Merzbow (Masami Akita), Mats Gustafsson oder Balázs Pándi fallen, verlässt schon mal die gute Hälfte der Menschen den Raum – „viel zu abgedreht“ heisst es da, und weg sind sie. Die andere Hälfte bleibt gespannt vor Ort und schaut und hört erst einmal hin. Fallen gar alle drei Namen gemeinsam, dünnt sich wahrscheinlich die Gesamtsituation noch deutlicher aus. Was ist zunächst die Erwartung? Nun, explosive Freejazz-Attacken, apokalyptische Geräusche und Exzesse. Legt man die Scheibe(n) aber ein, kommt ein völlig anderes Bild zum Vorschein. Die drei Musiker spielen fast zärtlich miteinander. Vier Plattenseiten mit je einem langen Stück erlauben uns einen intimen Blick in ein geradezu meditatives Zusammenspiel. Völlig freiformatige Improvisationen mit viel Zeit zum Erkunden des Augenblickes sind zu hören. Freilich kommen sie nicht ohne die erwarteten Ausbrüche und Eskapaden aus, jedoch finden sie immer wieder zurück zu Ruhe und fast besinnlicher Innenschau. Das ganze Album ist ein hingeworfenes Kunstwerk, ein tongewordener Moment, eine Begegnung. Das ist das Faszinierende und gleichzeitig das Problem, denn entweder man ist in der Lage und/oder in der Stimmung, dem Fluss der Klänge zu folgen, dann versinkt man darin, oder der Schlüssel passt überhaupt nicht in das Schlüsselloch, dann wird man mit der Musik überhaupt nichts anfangen können. Es hilft also nichts: Ausprobieren! RareNoiseRecords · And We Went Home (from ‚Cuts Open‘) Pándi: “For me, every possibility to play with the trio is special,” . “We can play together [only on rare occasions], so whenever it happens, we give it our all. -

João Gilberto

SEPTEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Find Doc // Merzbow Albums (Music Guide)

3LKZT0LXCYFS < Kindle # Merzbow albums (Music Guide) Merzbow albums (Music Guide) Filesize: 3.43 MB Reviews This pdf may be worth buying. It is actually filled with knowledge and wisdom Your daily life span will be convert as soon as you comprehensive reading this article publication. (Ms. Earline Schultz) DISCLAIMER | DMCA QCIGK2WHGNOO \\ eBook // Merzbow albums (Music Guide) MERZBOW ALBUMS (MUSIC GUIDE) Reference Series Books LLC Jun 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x192x19 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Commentary (music and lyrics not included). Pages: 29. Chapters: Merzbow discography, 13 Japanese Birds, Batztoutai with Memorial Gadgets, Merzbient, Merzbeat, Camouflage, Klatter, Jigokuhen, Nil Vagina Mail Action, Sun Baked Snow Cave, Aka Meme, Eucalypse, Merzbuta, Cloud Cock OO Grand, Minazo Vol. 1, Hiranya, Frog+, Ecobondage, Music for Bondage Performance, Antimonument, Gra, 1930, Tamago, Merzbuddha, Noisembryo, Venereology, Merzbear, Green Wheels, Rod Drug 93, Pulse Demon, Sphere, Dadarottenvator, Aqua Necromancer, Tauromachine, Anicca, Zophorus, Pinkream, Door Open at 8 am, Collection 5, Crocidura Dsi Nezumi, Amlux, Merzbird, Senmaida, F.I.D., Metamorphism, Music for the Dead Man 2: Return of the Dead Man, Normal Music, Space Metalizer, Music for Bondage Performance 2, Remblandt Assemblage, Sha Mo 3000, Merzzow, Severances, Metal Acoustic Music, Rainbow Electronics, Collection 4, Coma Berenices, Oersted, Dharma, Protean World, Storage, Age of 369, Merzcow, Hodosan,