Aaml - Massachusetts Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Tour Britain T , CHER and Gregg Allman Are Confirmed to Play Their Guitar and Slide -Guitar, Steve Beckneirer Lead Itra Debut Concert Tour Together with Guitar

-*row, UCTODer MM. MT/ NEWSDESK...NEWSDESK...NEWSDESK...News Editor...Jim Evans...01-836 1522 Cher and Allman . to tour Britain t , CHER and Gregg Allman are confirmed to play their guitar and slide -guitar, Steve Beckneirer lead _ItrA debut concert tour together with guitar. 7ig series of British Nell Larson keyboards, Gene Dinwiddle Dame and Bill dates in November Liverpool Empire 14, Birmingham Stewart drums f Hippodrome is. Glasgow Apollo 20 Manchester Apollo To coincide with the tour WEA release Cher and IS, London Rainbow. 24 Gregg's album 'Two The Hard Way' on November 4. tip Tickets are available now from box offices and usual The LP is credited to Allman and Woman. Titles range ' w agencies, priced C2 50. C2 and Ll. 50 from Smokey Robinson's A Hold On >. The Cher 'You've Really Got Allman Band comprises. Ricky Hirsch Me' to Jackson Browne's 'Shadow Dream Song'. 1% fr ENZ RETURN NEW Zealand outfit Split Enz have returned to Britain after a two -month tour of Australia where both their album DIrrythmia' and single 'My Mistake' are high in the charts. They kick oft their third UK tour at Birmingham Barbarellas on November 4 and 1111 6. They continue: Plymouth Castaways Vow November 7, Liverpool Eric's 11 and 12, London Roundhouse 13, Doncaster Outlook 14. Manchester Poly 15, Keels University 16. St " r* at Albans Civic 19, Warwick University 24, 4 Harrogate PG's 28, Retard Porterhouse 26. Further dates are expected to be added. SPI IT E.%7 starts November - 0 , T Nolan hired by a British horn section They were filmed at I E! II A Ili e! I I Tickets are available LA's Whiskey earlier _ from the London - Heartbreaker Palla- this year. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Lita Ford and Doro Interviewed Inside Explores the Brightest Void and the Shadow Self

COMES WITH 78 FREE SONGS AND BONUS INTERVIEWS! Issue 75 £5.99 SUMMER Jul-Sep 2016 9 771754 958015 75> EXPLORES THE BRIGHTEST VOID AND THE SHADOW SELF LITA FORD AND DORO INTERVIEWED INSIDE Plus: Blues Pills, Scorpion Child, Witness PAUL GILBERT F DARE F FROST* F JOE LYNN TURNER THE MUSIC IS OUT THERE... FIREWORKS MAGAZINE PRESENTS 78 FREE SONGS WITH ISSUE #75! GROUP ONE: MELODIC HARD 22. Maessorr Structorr - Lonely Mariner 42. Axon-Neuron - Erasure 61. Zark - Lord Rat ROCK/AOR From the album: Rise At Fall From the album: Metamorphosis From the album: Tales of the Expected www.maessorrstructorr.com www.axonneuron.com www.facebook.com/zarkbanduk 1. Lotta Lené - Souls From the single: Souls 23. 21st Century Fugitives - Losing Time 43. Dimh Project - Wolves In The 62. Dejanira - Birth of the www.lottalene.com From the album: Losing Time Streets Unconquerable Sun www.facebook. From the album: Victim & Maker From the album: Behind The Scenes 2. Tarja - No Bitter End com/21stCenturyFugitives www.facebook.com/dimhproject www.dejanira.org From the album: The Brightest Void www.tarjaturunen.com 24. Darkness Light - Long Ago 44. Mercutio - Shed Your Skin 63. Sfyrokalymnon - Son of Sin From the album: Living With The Danger From the album: Back To Nowhere From the album: The Sign Of Concrete 3. Grandhour - All In Or Nothing http://darknesslight.de Mercutio.me Creation From the album: Bombs & Bullets www.sfyrokalymnon.com www.grandhourband.com GROUP TWO: 70s RETRO ROCK/ 45. Medusa - Queima PSYCHEDELIC/BLUES/SOUTHERN From the album: Monstrologia (Lado A) 64. Chaosmic - Forever Feast 4. -

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Thursday, May 19, 2016 9:46:04 AM School: Saint Thomas More High School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Thursday, May 19, 2016 9:46:04 AM School: Saint Thomas More High School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 8458 EN Compost Critters Lavies, Bianca U 6.9 0.5 2,503 NF 14807 EN Dragon's Pearl, The Lawson, Julie LG 4.4 0.5 1,790 F 8469 EN Great Art Adventure, The Knox, Bob U 7.1 0.5 795 NF 7047 EN Judy Scuppernong Seabrooke, Brenda U 4.9 0.5 3,270 F 87332 EN Pendragon: The Guide to the MacHale, D.J. U 6.4 0.5 2,704 F Territories of Halla 8489 EN Shadows of Night Bash, Barbara UG 5.8 0.5 1,267 NF 66080 EN After the Death of Anna Gonzales Fields, Terri U 3.9 1.0 6,869 F 145213 EN Bad Island TenNapel, Doug U 2.3 1.0 5,624 F 127517 EN Blizzard! Nobleman, Mark Tyler U 3.1 1.0 4,942 F 59113 EN Carver: A Life in Poems Nelson, Marilyn U 5.9 1.0 9,377 NF 164617 EN Coaltown Jesus Koertge, Ron UG 3.1 1.0 10,394 F 8460 EN Digging up Tyrannosaurus Rex Horner, John U 6.1 1.0 3,753 NF 8465 EN Elephants Calling Payne, Katharine U 5.2 1.0 3,379 NF 32206 EN Frenchtown Summer Cormier, Robert U 6.4 1.0 8,031 F 62557 EN Girl Coming in for a Landing: A Wayland, April Halprin U 4.2 1.0 7,880 F Novel in Poems 104774 EN Hard Hit Turner, Ann U 5.1 1.0 4,885 F 127818 EN In Odd We Trust Chan, Queenie U 2.8 1.0 8,114 F 152673 EN Lies, Knives and Girls in Red Koertge, Ron UG 4.3 1.0 6,859 F Dresses 140486 EN Lightning Thief: The Graphic Venditti, Robert U 3.1 1.0 10,290 F Novel, The 8477 EN Monarchs Lasky, Kathryn U 6.8 1.0 6,558 NF 8483 EN On the Brink of Extinction Arnold, -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

MONTEVERDI, C.: Madrigals, Book 8 (Il Ottavo Libro De Madrigali, 1638) 8.573755-58

MONTEVERDI, C.: Madrigals, Book 8 (Il Ottavo Libro de Madrigali, 1638) 8.573755-58 www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=8.573755-58 MADRIGALI GUERRIERI ET AMOROSI. LIBRO OTTAVO, 1638 MADRIGALI GUERRIERI ET AMOROSI. EIGHTH BOOK OF MADRIGALS, 1638 CD 1 CD 1 MADRIGALI GUERRIERI MADRIGALI GUERRIERI ALTRI CANTI D’AMOR LET OTHERS SING OF CUPID a sei voci con doi violini e quattro viole for six voices, two violins and four viols (Sonetto d’autore anonimo) (Sonnet; anon.) [1] Sinfonia a doi violini e una viola da braccio [1] Sinfonia for two violins and viola da braccio che va inanzi al madrigal che segue to introduce the madrigal that follows [2] Altri canti d’Amor, tenero arciero, [2] Let others sing of Cupid, the gentle archer, i dolci vezzi e i sospirati baci, of his sweet charms and sighing kisses, narri gli sdegni e le bramate paci, let them tell of quarrels and of the longed-for truces quand’unisce due alme un sol pensiero. when two souls are united by a single thought. [3] Di Marte io canto furibundo e fiero, [3] I sing of a proud and raging Mars, i duri incontri e le battaglie audaci. of his bitter conflicts and valiant battles. Fo nel mio canto bellicoso e fiero With my fierce and warlike song strider le spade e bombeggiar le faci. I make swords clash and torches blaze. [4] Tu, cui tessuta han di Cesare alloro [4] You for whom an immortal crown la corona immortal mentre Bellona, of imperial laurel has been woven, gradite il verde ancor novo lavoro, accept Bellona’s wreath, still green and fresh, [5] che mentre guerre canta e guerre sona, [5] for in our songs and music of war, o gran Fernando, l’orgoglioso coro o mighty Ferdinand, our proud choir del tuo sommo valor canta e ragiona. -

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth Director

I Fagiolini Barokksolistene Robert Hollingworth director CHAN 0760 CHANDOS early music © Graham Slater / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Bust of Claudio Monteverdi by P. Foglia, Cremona, Italy 3 4 Zefiro torna, e ’l bel tempo rimena 3:29 (1567 – 1643) Claudio Monteverdi from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Anna Crookes, Clare Wilkinson, Robert Hollingworth, Nicholas Mulroy, 1 Questi vaghi concenti 7:06 Charles Gibbs from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) Choir I: Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Richard Wyn Roberts, 5 Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti 6:13 Nicholas Mulroy, Charles Gibbs from Scherzi musicali cioè arie, & madrigali in stil Choir II: Anna Crookes, William Purefoy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith, recitativo… (1632) Eamonn Dougan Nicholas Mulroy, Nicholas Hurndall Smith Strings: Barokksolistene Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Continuo: Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone), Joy Smith, Steven Devine Catherine Pierron (harpsichord) 2 T’amo, mia vita! 2:53 6 Ohimè, dov’è il mio ben? 4:44 from Il quinto libro de madrigali (1605) from Concerto. Settimo libro de madrigali (1619) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, Charles Gibbs Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) Continuo: Joy Smith, Eligio Quinteiro (chitarrone) 7 3 Ohimè il bel viso 4:51 Si dolce è ’l tormento 4:27 from Carlo Milanuzzi: from Il sesto libro de madrigali (1614) Quarto scherzo delle ariose (1624) Julia Doyle, Clare Wilkinson, Nicholas Mulroy, Eamonn Dougan, vaghezze… Charles Gibbs Nicholas -

Our Weekend Enjoyment Section 4 in Atlantic City Convicted

Today: Our Weekend Enjoyment Section SEE PAGES 7-10 The Weather Mostly sunny and mild THEMILY , FINAL " ' "• • today, high in low 60s. In- Kcil Hank, Freehold creasing cloudiness tonight. 5 Long Branch Tomorrow, chance of rain. T 7 EDITION 30 PAGES Monmouth County's Outstanding Homo Ncwspapor VOL.95 NO. 175 RED BANK, N.J. FRIDAY, MARCH 9,1973 TEN CENTS nniiluiMuiillliiiinilliiiilliiiiiiiiiliiilMiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii i iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiiini iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiimiiiiiiuii IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIII iiiiiiiiiiinii IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMIIIIIIIIIIH iiiiiuiiiiiii mini iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniu Energy Crisis Weight, Cause, Cures Argued By SHERRY FIGDORE ground of the speakers. ment policies on the economic energy fence, Richard J. Sulli- "scapy curve, about to go "The electrical energy sys- While this country contains such as hydro power, solar 'Congressman James J. control of fuel source devel- van, commissioner of the through the ceiling." tem cannot continue to double one-third of the world's coal and geothermal energy, and JAMESBURG - The Howard, D-N.J., chairman of opment. State Department of Environ- And David F. Moore, Exec- every 10 years for very long," deposits, it is still not econom- fusion reactors, are nowhere United States is already in the the new House subcommittee Kerryn King, a senior vice mental Protection, said "En- utive director of the North Mr. Moore continued. "The ically feasible to develop near ready to provide a prac- grip of an energy crisis, ac- on energy, was the only op- president of Texaco, Inc., pre- vironmentalists are not the Jersey Conservation Founda- numbers of plants needed them.in the face of lower- tical source of energy and cording to a dozen representa-. -

03 P&M Book.Qxd

DESIGN, DEVELOP, BUILD, RACE, WIN UNDEFEATED 2004 CHAMPIONS A TEAM AT THE TOP OF ITS GAME Contents It has been a wild year. Think about it: We just got settled into our new A Team at the Top of its Game – Our Perfect Season . .2 Photos courtesy of Phil Binks, building, and now a big addition is under construction; our Cadillac CTS-V One-Two the Hard Way – 24 Hours of Le Mans . 4 Dan Boyd, team was in its first racing season; a new Pontiac GTO program was in ALMS Goes Green for 2004 – Mobil 1 12 Hours of Sebring . 12 Richard Dole, development; and our Corvette customer project for the Selleslagh Racing Gregory Johnson, The Masters – Ron and Johnny Go 3 for 3 at Mid-Ohio . .18 Robert Mochernuk, team in Belgium continued. Robin Pratt, Corvettes at Rush-Hour – New England Grand Prix, Lime Rock . .20 Richard Prince, In the midst of all this activity, Corvette Racing was never defeated in Bittersweet Victory – Grand Prix of Sonoma, Infineon Raceway . 22 Steve Robertson. 2004. We had a perfect season, and those are incredibly rare in auto Printed with permission. Hot One – Grand Prix of Portland . 24 racing. The reason for our success is the remarkable efforts exerted by Copyright © 2004 Pratt every person involved. This is a team at the top of its game, and our Gavin and Beretta Beat the Jinx – Toronto Grand Prix of Mosport . 26 & Miller Engineering & Fabrication, Inc. sincere thanks and appreciation for a job well done go out to every Two Straight – Road America 500 . -

San Fpancisco Foqhoun Shroud Scientists Come To

san fpancisco foqhoun FEBRUARY 19, 1982 UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA VOLIME 77 MMBFR 12 —2 of 40 Make Presentation Shroud Scientists Come To USF by M.M. Showalter The mysterious Shroud of Turin Dr. Kim Summerhays, Chairman pointed out tnat the question, will be the topic of a lecture given by of the USF Department of therefore, would be what could act two distinguished scientists on Chemistry, is the man primarily through space like this. "The laser February 20 in the McLaren Center behind the presentation. In an might be the closest analogy." at 7:30 p.m. The event is sponsored interview earlier this week, he In the second part ofthe inquiry, by the USF College of Science. discussed some of the points of the question of the identity of the Robert Bucklin and Donald Lynn interest and importance concerning figure, evidence of what is seen on will report the results of their this inquiry. the body image is examined in order research as members of the select Said Summerhays. "The history to give clues to the identity of the international team of scientists of the Shroud can be traced back to person. Some conclusions named by invited by the Archbishop of Turin the early fourteenth century. The Dr. Summerhays were that the to examine the linen cloth believed belief is that it was brought back person was of Semitic facial to be the burial shroud of Jesus from Constantinople during one of structure, that the pollen on the Christ. the Crusades. The image is that of an cloth indicated the linen to be of Bucklin is a medical examiner, apparently crucified person Middle Eastern origin and that the lawyer, and pathologist recently imprinted lightly on the cloth in the figure died of asphyxiation, as is so affiliated with the Los Angeles manner of a photographic negative." in the case of crucifixion. -

Versiunea Coja

Evenimentele din de am să, extrag doar datele îl susținea cu tărie!). Noua decât evenimentele care i-au cembrie 1989, dintre care privind asasinarea lui Nicolae bancă internațională urma să adus de fapt sfârșitul. multe sunt învăluite în mister, Ceaușescu. Potrivit acestei Versiunea Coja ia ființă în martie ’90, cu un Să fi fost moartea lui continuă să preocupe un versiuni, asasinarea con capital de 15 miliarde dolari, Ceaușescu dictată de finanța ' că se situează forțe oculte, fără naționale ar înceta să mai număr mare de cercetători, ducătorului statului român era din care cinci ar fi fost internațională pentru istoriografi, publiciști. O hotărâtă încă de la denunțarea să le numească) au fost uimite existe, dând pur și simplu contribuția României și câte înlăturarea unui inamic versiune relativ senzațională unilaterală de către acesta a de această performanță. O țară faliment. alte cinci din partea Libiei și periculos? Este o versiune pe cu privire la moartea lui acordurilor cu organismele care își achită toate datoriile nu Conform datelor prezentate Iranului. Dobânzile practicate care o menționăm, printre Nicolae Ceaușescu am întâlnit financiare internaționale ca mai plătește dobânzi la de Ion Coja, Ceaușescu. in urmau să fie foarte mici, între multe altele ', care încearcă să în cartea lui Ion Coja: “Marele urmare a efortului dramatic, împrumuturi, lipsind orga megalomania lui, nu numai că 3-5 %. Acesta pare să fie și manipulator și asasinarea lui plin de suferințe al poporului nismele financiare de profitul a întors spatele capitalului motivul neașteptatei vizite a lui descifreze evenimentele din • Culianu, Ceaușescu, lorga". român, de a achita o datorie câștigat în urma acestor mondial, ci' a intenționat să Ceaușescu în Iran, după 1989, care sunt încă Pentru a nu v& răpi externă de peste 13 miliarde împrumuturi. -

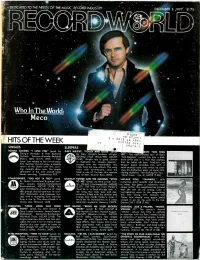

Record-World-1977-12

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC RECORD INDUS -R? DECEMBER 3i9 S1 75 Who In The World: 3 HO NOINv N °VWIS 1176 HITS OF THE WEEK OS013d : 9 3/1 ti )) o SINGLES SLEEPERS DONNA SUMMER, "I LOVE YOU" (prod. by GARY WRIGHT, "TOUCH AND WN TWO THEN Giorgio Moroder &PeteBellotte) by Gcry Wright)(writers:Wright- LEFT." The sophisticated soul of Boz's (writers: Summer-Moroder-Bellotte) Reicheg)(High Wave/WB, ASCAP) "Silk Degrees" turned him into a plat- (Rick's,BMI)(3:17).With"I Feel (3:30). Wright hos a good chance inum artist and itis from that plateau Love- just added to her list of major tcduplicatehis "Dream Weaver" that he takes off here.Producer Joe hits, Summer should enjoy a speedy successwiththememorabletitle Wissertagainprovideshimwith a return to the charts with this swirl- track from his new album. The song solid musical core cver which he exer- ing, melodic disco tune. The simple rockswithsynthesizers,andthe cises his distinctive tenor on some stim- sentimentinthetitleshould keep hook is one of tl-e best this veteran ulating material: "Still Falling For You,- heads spinning. Casablanca 907. has written. Warner Bros. 8494. -Hard Times.- Col JC 34729 (7.98). COMMODORES, "TOO HOT TA TROT" (prod. GRAHAM PARKER AND THE RUMOUR, "STICK NATALIE COLE, "THANKFUL."With by James Carmichael & group) (wri- TO ME" (prod. by Nick Lowe) (wri- numerous gold records and Grammys ters: group) (Jobete/Commodores itt ter:Parker) (Inte-song-USA, ASCAP) inwhat has been arelatively short Entertainment, ASCAP) (3:30).This (":::27).Thetitlecut from Parker's MotnwN career so far, this songstress has proved most consistently productive of male thirdIpisa hard -driving rock'n' -hatshe can do no wrong.