Housing for the Working Classes in the East End of London, 1890-1907

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Poverty and Philanthropy in the East

KATHARINE MARIE BRADLEY POVERTY AND PHILANTHROPY IN EAST LONDON 1918 – 1959: THE UNIVERSITY SETTLEMENTS AND THE URBAN WORKING CLASSES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD IN HISTORY CENTRE FOR CONTEMPORARY BRITISH HISTORY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between the university settlements and the East London communities through an analysis their key areas of work during the period: healthcare, youth work, juvenile courts, adult education and the arts. The university settlements, which brought young graduates to live and work in impoverished areas, had a fundamental influence of the development of the welfare state. This occurred through their alumni going on to enter the Civil Service and politics, and through the settlements’ ability to powerfully convey the practical experience of voluntary work in the East End to policy makers. The period 1918 – 1959 marks a significant phase in this relationship, with the economic depression, the Second World War and formative welfare state having a significant impact upon the settlements and the communities around them. This thesis draws together the history of these charities with an exploration of the complex networking relationships between local and national politicians, philanthropists, social researchers and the voluntary sector in the period. This thesis argues that work on the ground, an influential dissemination network and the settlements’ experience of both enabled them to influence the formation of national social policy in the period. -

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T. Husbands Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Sound and Fury Christopher T. Husbands Emeritus Reader in Sociology London School of Economics and Political Science London, UK Additional material to this book can be downloaded from http://extras.springer.com. ISBN 978-3-319-89449-2 ISBN 978-3-319-89450-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89450-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950069 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and trans- mission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Abercrombie's Green-Wedge Vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944

Abercrombie’s green-wedge vision for London: the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944 Abstract This paper analyses the role that the green wedges idea played in the main official reconstruction plans for London, namely the County of London Plan 1943 and the Greater London Plan 1944. Green wedges were theorised in the first decade of the twentieth century and discussed in multifaceted ways up to the end of the Second World War. Despite having been prominent in many plans for London, they have been largely overlooked in planning history. This paper argues that green wedges were instrumental in these plans to the formulation of a more modern, sociable, healthier and greener peacetime London. Keywords: Green wedges, green belt, reconstruction, London, planning Introduction Green wedges have been theorised as an essential part of planning debates since the beginning of the twentieth century. Their prominent position in texts and plans rivalled that of the green belt, despite the comparatively disproportionate attention given to the latter by planning historians (see, for example, Purdom, 1945, 151; Freestone, 2003, 67–98; Ward, 2002, 172; Sutcliffe, 1981a; Amati and Yokohari, 1997, 311–37). From the mid-nineteenth century, the provision of green spaces became a fundamental aspect of modern town planning (Dümpelmann, 2005, 75; Dal Co, 1980, 141–293). In this context, the green wedges idea emerged as a solution to the need to provide open spaces for growing urban areas, as well as to establish a direct 1 connection to the countryside for inner city dwellers. Green wedges would also funnel fresh air, greenery and sunlight into the urban core. -

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

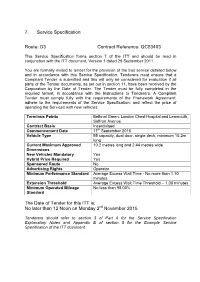

D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 the Date of Tender for This ITT Is

7. Service Specification Route: D3 Contract Reference: QC53403 This Service Specification forms section 7 of the ITT and should be read in conjunction with the ITT document, Version 1 dated 29 September 2011. You are formally invited to tender for the provision of the bus service detailed below and in accordance with this Service Specification. Tenderers must ensure that a Compliant Tender is submitted and this will only be considered for evaluation if all parts of the Tender documents, as set out in section 11, have been received by the Corporation by the Date of Tender. The Tender must be fully completed in the required format, in accordance with the Instructions to Tenderers. A Compliant Tender must comply fully with the requirements of the Framework Agreement; adhere to the requirements of the Service Specification; and reflect the price of operating the Services with new vehicles. Terminus Points Bethnal Green, London Chest Hospital and Leamouth, Saffron Avenue Contract Basis Incentivised Commencement Date 17th September 2016 Vehicle Type 55 capacity, dual door, single deck, minimum 10.2m long Current Maximum Approved 10.2 metres long and 2.44 metres wide Dimensions New Vehicles Mandatory Yes Hybrid Price Required Yes Sponsored Route No Advertising Rights Operator Minimum Performance Standard Average Excess Wait Time - No more than 1.10 minutes Extension Threshold Average Excess Wait Time Threshold – 1.00 minutes Minimum Operated Mileage No less than 98.00% Standard The Date of Tender for this ITT is: nd No later than 12 Noon on Monday 2 November 2015 Tenderers should refer to section 3 of Part A for the Service Specification Explanatory Notes and Appendix B of section 5 for the Example Service Specification of the ITT document. -

U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan Relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics

Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics Historical background: Philip Corrigan? The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a specialist social science university. It was founded in 1894 by Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Custodial History: Donated by Philip Corrigan, Department of Sociology and Social Administration, Durham University, October 1974 Description: Material about the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) including files relating to the history of the institution, and miscellaneous files referring to accounts, links with other countries, particularly Southern Rhodesia, and aspects of student militancy and student unrest. Arrangement: U DPC/1-8 Materials (mainly photocopies) for a history of the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1919- 1973 U DPC/9-14 Miscellaneous files relating to LSE and higher education, 1966-1973 Extent: 0.5 linear metres Access Conditions: Access will be given to any accredited reader page 1 of 8 Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC/1 File. 'General; foundation; the Webbs' containing the 1919-1970 following items relating to the London School of Economics and Political Science: (a) Booklist and notes (4pp.). No date (b) 'The London School of Economics and Political Science' by D. Mitrany ('Clare Market Review Series', no.1, 1919) (c) Memorandum and Articles of Association of the LSE, dated 1901, reprinted 1923. (d) 'An Historical Note' by Graham Wallas ('Handbook of LSE Students' Union', 1925, pp.11-13) (e) 'Freedom in Soviet Russia' by Sidney Webb ('Contemporary Review', January 1933, pp.11-21) (f) 'The Beginnings of the LSE'' by Max Beer ('Fifty Years of International Socialism', 1935, pp.81-88) (g) 'Graduate Organisations in the University of London' by O.S. -

N277 Islington – Mile End – Crossharbour

N277 Islington – Mile End – Crossharbour N277 Sunday night/Monday morning Islington White Lion Street 0010 0035 0054 0118 0143 0210 0240 0310 0340 0410 0434 0504 0534 Islington Angel (Upper Street) 0011 0036 0055 0119 0144 0211 0241 0311 0341 0411 0435 0505 0535 Highbury Corner St Paul's Road 0018 0043 0102 0126 0151 0217 0247 0317 0347 0417 0441 0511 0541 Dalston Junction Dalston Lane 0025 0050 0109 0133 0158 0223 0253 0322 0352 0422 0446 0516 0546 Hackney Central Station Graham Rd. 0030 0055 0114 0138 0202 0227 0257 0326 0356 0426 0450 0520 0550 Lauriston Road Church Crescent 0037 0102 0121 0145 0209 0234 0304 0332 0402 0432 0455 0525 0555 Mile End Grove Road 0042 0107 0126 0150 0214 0239 0309 0337 0407 0436 0459 0529 0559 Limehouse Burdett Road 0047 0112 0131 0155 0218 0243 0313 0341 0411 0440 0503 0533 0603 Canary Wharf (DLR) Station 0052 0117 0136 0200 0223 0248 0318 0346 0415 0444 0507 0537 0607 Westferry Road Cuba Street 0054 0119 0138 0202 0225 0250 0320 0348 0418 0447 0511 0541 0611 Millwall Dock Bridge 0057 0122 0141 0204 0227 0252 0322 0350 0420 0450 0514 0544 0614 Westferry Road East Ferry Road 0100 0125 0144 0207 0230 0255 0325 0353 0423 0453 0517 0547 0617 Crossharbour Asda 0103 0128 0147 0210 0233 0258 0328 0356 0426 0456 0520 0550 0620 N277 Monday night/Tuesday morning to Thursday night/Friday morning Islington White Lion Street 0010 0035 0054 0118 0143 0210 0240 0310 0340 0410 0434 0504 0534 Islington Angel (Upper Street) 0011 0036 0055 0119 0144 0211 0241 0311 0341 0411 0435 0505 0535 Highbury Corner St Paul's Road 0018 0043 0102 0126 0151 0217 0247 0317 0347 0417 0441 0511 0541 Dalston Junction Dalston Lane 0025 0050 0109 0133 0158 0223 0253 0322 0352 0422 0446 0516 0546 Hackney Central Station Graham Rd. -

Denbury House Bow Road

Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD OIEO £400,000 FOR SALE REF: 2534034 2 Bed, Apartment, Private Garden, Permit Parking South Facing Private Garden - Low Rise Development - Chain Free - Two Bedroom Apartment - Ex Local Authority - Located moments walk from Bromley by Bow Station Guide Price £395,000 to £410,000. Wonderful two double bedroom apartment boasting large south facing private garden, located in this well kept low rise ex local authority development walking distance to Bromley by Bow Tube Station and Devon's road DLR Stations with easy access to the City and Canary Wharf. The property consists large bright reception with access to the private garden, modern kitchen, separate WC and family bathroom, two good sized double bedrooms, one with fitted storage. Offer... continued below Train/Tube - Bromley-by-Bow, Bow Church, Mile End, Bow Road Local Authority/Council Tax - Tower Hamlets Tenure - Leasehold Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Reception Reception Alt 1 Reception Alt 2 Kitchen Master Bedroom Second Bedroom Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Second Bedroom Alt Bathroom Exterior Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Please note that this floor plan is produced for illustration and identification purposes only. -

Alternative Options Investigated to Address the Issues at Blackwall Tunnel

Alternative options considered to address the issues at the Blackwall Tunnel We have considered a wide range of options for schemes to help address the transport problems of congestion, closures and incidents, and resilience at the Blackwall Tunnel and believe that our proposed Silvertown Tunnel scheme is the best solution. This factsheet examines a number of potential alternative schemes, including some which were suggested by respondents to our previous consultation, and explains why we do not consider them to be feasible solutions to the problems at the Blackwall Tunnel. Further detail on each alternative as well as other alternatives is included in the Preliminary Case for the Scheme, which can be found at www.tfl.gov.uk/Silvertown-tunnel. Building a bridge between Silvertown and the Greenwich Peninsula, rather than a tunnel We have considered building a bridge at Silvertown, instead of a tunnel. However, any new bridge built in east London needs to provide at least 50m of clearance above the water level to allow tall sea-going shipping to pass beneath safely. A bridge with this level of clearance would require long, sloping approach ramps. Such ramps would create a barrier within the local area, as well as dramatically affecting the visual environment and going against local authorities’ development plans. A high-level bridge would also not be feasible in the current location due to it’s proximity to the Emirates Air Line cable car. We also considered the option of a lifting bridge (like Tower Bridge). This could be constructed at a lower level, with less impact on the local area. -

Stepney in Peace and War the Paintings of Rose L. Henriques

NEWSLETTER OF TOWER HAMLETS LOCAL HISTORY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES LH&A NEWS November-December 2013 Stepney in Peace and War The paintings of Rose L. Henriques The Foothills, 'Tilbury', bombed second time. Watercolour on paper, Rose L. Henriques. c1941. Our new exhibition is a rare opportunity to see highlights from our collections of paintings by the Jewish philanthropist Rose L. Henriques (1889-1972) which launches here on Thursday 28 November at 6.30pm. This event is open to the public and is co-hosted with the Jewish East End Celebration Society. With her husband Sir Basil, Lady Rose Henriques founded the St George's Jewish Settlement in Betts St, Stepney in 1919. Here, the Henriques developed social welfare facilities and services for the deprived local community ranging from youth clubs to washrooms and open to Jews and non-Jews alike. The Settlement was able to expand into its own new premises in Berner Street in 1929 thanks to funding from philanthropist Bernhard Baron, after whom the building was renamed. Rose was an avid artist, serving on the board of the Whitechapel Gallery, and the watercolours in our collection are a unique record of Stepney around the time of the Second World War. Focussing on the regular activities and everyday landscapes of the besieged borough, her subjects include the clear-up and triage activities of the Civilian Defence Service, the controversial air raid shelter known as "Tilbury", and scenes of bombed out synagogues and churches. She also painted everyday life at the Settlement building where she and Basil lived. This exhibition has been curated by staff with the expert voluntary help of art researcher Sara Ayad.