On the Morphological Relationships of the Molluseoida and Ccelenterata, and of Their Leading Members, Inter Se

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Ghost and Mud Shrimp

Zootaxa 4365 (3): 251–301 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4365.3.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C5AC71E8-2F60-448E-B50D-22B61AC11E6A Parasites (Isopoda: Epicaridea and Nematoda) from ghost and mud shrimp (Decapoda: Axiidea and Gebiidea) with descriptions of a new genus and a new species of bopyrid isopod and clarification of Pseudione Kossmann, 1881 CHRISTOPHER B. BOYKO1,4, JASON D. WILLIAMS2 & JEFFREY D. SHIELDS3 1Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West @ 79th St., New York, New York 10024, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biology, Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York 11549, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Aquatic Health Sciences, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William & Mary, P.O. Box 1346, Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 4Corresponding author Table of contents Abstract . 252 Introduction . 252 Methods and materials . 253 Taxonomy . 253 Isopoda Latreille, 1817 . 253 Bopyroidea Rafinesque, 1815 . 253 Ionidae H. Milne Edwards, 1840. 253 Ione Latreille, 1818 . 253 Ione cornuta Bate, 1864 . 254 Ione thompsoni Richardson, 1904. 255 Ione thoracica (Montagu, 1808) . 256 Bopyridae Rafinesque, 1815 . 260 Pseudioninae Codreanu, 1967 . 260 Acrobelione Bourdon, 1981. 260 Acrobelione halimedae n. sp. 260 Key to females of species of Acrobelione Bourdon, 1981 . 262 Gyge Cornalia & Panceri, 1861. 262 Gyge branchialis Cornalia & Panceri, 1861 . 262 Gyge ovalis (Shiino, 1939) . 264 Ionella Bonnier, 1900 . -

Northern Adriatic Bryozoa from the Vicinity of Rovinj, Croatia

NORTHERN ADRIATIC BRYOZOA FROM THE VICINITY OF ROVINJ, CROATIA PETER J. HAYWARD School of Biological Sciences, University of Wales Singleton Park, Swansea SA2 8PP, United Kingdom Honorary Research Fellow, Department of Zoology The Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD, UK FRANK K. MCKINNEY Research Associate, Division of Paleontology American Museum of Natural History Professor Emeritus, Department of Geology Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 270, 139 pp., 63 ®gures, 1 table Issued June 24, 2002 Copyright q American Museum of Natural History 2002 ISSN 0003-0090 2 BULLETIN AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY NO. 270 CONTENTS Abstract ....................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................... 5 Materials and Methods .......................................................... 7 Systematic Accounts ........................................................... 10 Order Ctenostomata ............................................................ 10 Nolella dilatata (Hincks, 1860) ................................................ 10 Walkeria tuberosa (Heller, 1867) .............................................. 10 Bowerbankia spp. ............................................................ 11 Amathia pruvoti Calvet, 1911 ................................................. 12 Amathia vidovici (Heller, 1867) .............................................. -

Using Dna to Figure out Soft Coral Taxonomy – Phylogenetics of Red Sea Octocorals

USING DNA TO FIGURE OUT SOFT CORAL TAXONOMY – PHYLOGENETICS OF RED SEA OCTOCORALS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE IN ZOOLOGY DECEMBER 2012 By Roxanne D. Haverkort-Yeh Thesis Committee: Robert J. Toonen, Chairperson Brian W. Bowen Daniel Rubinoff Keywords: Alcyonacea, soft corals, taxonomy, phylogenetics, systematics, Red Sea i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was performed in collaboration with C. S. McFadden, A. Reynolds, Y. Benayahu, A. Halász, and M. Berumen and I thank them for their contributions to this project. Support for this project came from the Binational Science Foundation #2008186 to Y. Benayahu, C. S. McFadden & R. J. Toonen and the National Science Foundation OCE-0623699 to R. J. Toonen, and the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries which provided an education & outreach fellowship for salary support. The expedition to Saudi Arabia was funded by National Science Foundation grant OCE-0929031 to B.W. Bowen and NSF OCE-0623699 to R. J. Toonen. I thank J. DiBattista for organizing the expedition to Saudi Arabia, and members of the Berumen Lab and the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology for their hospitality and helpfulness. The expedition to Israel was funded by the Graduate Student Organization of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Also I thank members of the To Bo lab at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology, especially Z. Forsman, for guidance and advice with lab work and analyses, and S. Hou and A. G. Young for sequencing nDNA markers and A. -

On a Collection of Hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from the Southwest Coast of Florida, USA

Zootaxa 4689 (1): 001–141 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4689.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:4C926BE2-D75D-449A-9EAD-14CADACFFADD ZOOTAXA 4689 On a collection of hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from the southwest coast of Florida, USA DALE R. CALDER1, 2 1Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2C6 E-mail: [email protected] 2Research Associate, Royal British Columbia Museum, 675 Belleville Street, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8W 9W2. Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by B. Bentlage: 9 Sept.. 2019; published: 25 Oct. 2019 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 DALE R. CALDER On a collection of hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from the southwest coast of Florida, USA (Zootaxa 4689) 141 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2019 ISBN 978-1-77670-799-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77670-800-0 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2019 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] https://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 4689 (1) © 2019 Magnolia Press CALDER Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................5 Introduction ................................................................................................5 -

Zvy Dubinsky Editors the World of Medusa and Her Sisters

Stefano Goff redo · Zvy Dubinsky Editors The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future The world of Medusa and her sisters Diversity and Distribution of Octocorallia 8 Carlos Daniel Pérez , Bárbara de Moura Neves , Ralf Tarciso Cordeiro , Gary C. Williams , and Stephen D. Cairns Abstract Octocorals are a group of striking presence in marine benthic communities. With approxi- mately 3400 valid species the taxonomy of the group is still not resolved, mainly because of the variability of morphological characters and lack of optimization of molecular mark- ers. Octocorals are distributed in all seas and oceans of the world, from shallow waters up to 6400 m deep, but with few cosmopolitan species (principally pennatulaceans). The Indo- Pacifi c is the region that holds the greatest diversity of octocorals, showing the highest level of endemism. However, endemism in octocorals as we know might be the refl ex of a biased sampling effort, as several punctual sites present high level of endemism (e.g. Alaska, Antarctica, South Africa, Brazil, Gulf of Mexico). Since around 75 % of described octocoral species are found in waters deeper than 50 m, increasing knowledge on octocoral diversity and distribution is still limited by the availability of resources and technologies to access these environments. Furthermore, the limited number of octocoral taxonomists limits prog- ress in this fi eld. Integrative taxonomy (i.e. morphology, molecular biology, ecology and biogeography) appears to be the best way to try to better understand the taxonomy of such a diverse and important group in marine benthic communities. Keywords Octocoral • Soft coral • Anthozoa • Worldwide distribution • Deep sea 8.1 Diversity in Octocorals of the World: C. -

A Resource Unit on Animal Regeneration a Thesis

A RESOURCE UNIT ON ANIMAL REGENERATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION ATLANTA UNIVERSITY, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY BOBBIE L. JOHNSON SCHOOL OF EDUCATION ATLANTA UNIVERSITY ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 1962 3 k 9^ DEDICATION This thesis is affectionately dedicated to my wife, Mrs. Patricia Grace Johnson, for her under¬ standing and encouragement, and to my children - Michael, Michele and Kassondra, B.L.J# ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank all persons who have made the success of this venture possible* Special words of appreciation, however, must go to Drs, E. K, Weaver and L* Boyd of the School of Education; Drs* G, E. Riley and M, L. Reddick of the Biology Department, Atlanta University; Dr, K, A, Huggins, Director of the National Science Foundation Academic Tear Institute; Drs* H, C. McBay and Roy Hunter, Jr, of Morehouse College, and Dr, Joe Hall, Superintendent of the Dade County (Florida) Public Schools, B,L,J, iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION Ü ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ...... 1 Rationale • 1 Evolution of the Problem • •••...••.•• 3 Contribution to Educational Knowledge. 3 Statement of the Problem U Purpose of the Study . U Limitation of the Study. U Definition of Terms U Materials ..... .•••• 5 Operational Steps 6 Method of Research «•••• •••• 8 Survey of Related Literature. ••••••••• 8 H. THE RESOURCE UNIT 13 Outline . * 13 Introductory Comments. •••.••••••••. 13 Orientation for the Teacher* Animal Regeneration 18 Introduction ....... 18 Universality of Regeneration 20 Source of the Cells of the Regenerate. 23 Extrinsic Factors in Regeneration, 2k Stimulus for Regeneration ......... -

Robert K. Josephson (1934–2016) Darrell R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2016) 219, 1420-1421 doi:10.1242/jeb.142034 OBITUARY Robert K. Josephson (1934–2016) Darrell R. Stokes* Professor Robert K. Josephson died at his home in Laguna Beach, California, on 6 February 2016 following a 3 month fight with lymphoma. Over a career spanning more than half a century, and numerous venues world-wide, he became widely known and venerated as a mentor, teacher, colleague, physiologist and friend. His path to distinction began as an undergraduate at Tufts University (1952–1956). It was at Tufts that he was influenced by K. D. Roeder and became interested in pursuing graduate work in behavioral physiology. In the sixties and seventies there was considerable interest amongst researchers in a variety of invertebrate animals as many displayed rather stereotypical motor behaviors driven by neural pathways with few components, and neurons that were large and amenable to electrophysiological studies. The stated goal of many was to understand the complete behavior of an organism based on the underlying neuromuscular systems. Bullock and Horridge’s (1965a,b) two-volume series, The Structure and Function of the Nervous Systems of Invertebrates, well attests to the thrust of research during that period. Not surprisingly, Bob went to Ted Bullock’s laboratory at UCLA to pursue graduate studies (1956–1960). Dissertation research in Bullock’s laboratory set Bob on the first of two career pathways, both of which identify him as an innovative, creative and trend-setting leader in behavioral physiology. The first pathway was the behavioral physiology of ‘simply’ organized metazoan animals – namely of the Coelenterata ( jellyfish, corals, hydroids); the second pathway was the physiology and design constraints of skeletal muscle. -

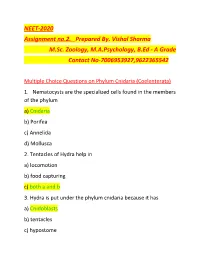

NEET-2020 Assignment No.2. Prepared By. Vishal Sharma M.Sc

NEET-2020 Assignment no.2. Prepared By. Vishal Sharma M.Sc. Zoology, M.A.Psychology, B.Ed - A Grade Contact No-7006953927,9622365542 Multiple Choice Questions on Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata) 1. Nematocysts are the specialized cells found in the members of the phylum a) Cnidaria b) Porifea c) Annelida d) Mollusca 2. Tentacles of Hydra help in a) locomotion b) food capturing c) both a and b 3. Hydra is put under the phylum cnidaria because it has a) Cnidoblasts b) tentacles c) hypostome d) interstitial cells 4. The poisonous fluid present in the nematocysts of Hydra is a) toxin b) Hypnotoxin c) venom d) Haematin 5. Nematocysts are the organs of a) sensation b) reproduction c) Defence and offence d) respiration 6. Hydra prevents self fertilization by being a) Protogynous b) hermaphrodite c) protandrous d) monoecious 7. The planula larva is found in the life history of a) Hydrozoan b) Anthozoan c) Scyphozoan d) All of the above 8. Polymorphic cnidarians are the members of the class a) Hydrozoa b) Scyphozoa c) Actinozoa d) None of these 9. Coral reef forming coelenterates belong to the class a) Hydrozoa b) Scyphozoa c) Actinozoa d) All of the above 10. Among coelenterates medusoid individuals are absent in members of the class a) Anthozoa b) Hydrozoa c) Scyphozoa d) None of these 11. Ephyra is the larval form of a) Sea anemone b) Aurellia c) Obelia d) Hydra 12. Six septa or six mesenteries are characteristic of a) Aurelia b) Hydra c) Obelia d) Sea anemone Sea anemone 13. Sea anemone is a) diploblastic, radially symmetrical animal b) diploblastic, bilaterally symmetrical animal c) triploblastic, radially symmetrical animal d) triploblastic, bilaterally symmetrical animal 14. -

A Sea Anemone of Many Names: a Review of the Taxonomy

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 706: 1–15A (2017)sea anemone of many names: a review of the taxonomy and distribution... 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.706.19848 SHORT COMMUNICATION http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A sea anemone of many names: a review of the taxonomy and distribution of the invasive actiniarian Diadumene lineata (Diadumenidae), with records of its reappearance on the Texas coast Zachary B. Hancock1, Janelle A. Goeke2, Mary K. Wicksten1 1 304 Butler Hall, 3258 Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-3258, USA 2 3029 Texas A&M University, Galveston, TX 77554-2853, USA Corresponding author: Zachary B. Hancock ([email protected]) Academic editor: B.W. Hoeksema | Received 27 July 2017 | Accepted 11 September 2017 | Published 4 October 2017 http://zoobank.org/91322B68-4D72-4F2C-BC33-A57D4AC0AB44 Citation: Hancock ZB, Goeke JA, Wicksten MK (2017) A sea anemone of many names: a review of the taxonomy and distribution of the invasive actiniarian Diadumene lineata (Diadumenidae), with records of its reappearance on the Texas coast. ZooKeys 706: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.706.19848 Abstract Diadumene lineata (Actiniaria: Diadumenidae) is a prolific invader of coastal environments around the world. First described from Asia, this sea anemone has only been reported once from the western Gulf of Mexico at Port Aransas, Texas. No subsequent sampling has located this species at this locality. The first record of the reappearance of D. lineata on the Texas coast from three locations in the Galveston Bay area is provided, and its geographic distribution and taxonomic history reviewed. -

Annex 5.1 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

CoP16 Doc. 43.1 (Rev. 1) Annex 5.1 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) Taxonomic Checklist of all CITES listed Coral species Based on information compiled in 2012 by the UNEP - World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) Reproduction for commercial purposes prohibited. CoP16 Doc. 43.1 (Rev. 1), Annex 5.1 – p. 1 Part I Coral Nomenclature References Babcock, R. 1990. Reproduction and development of the Blue Coral Heliopora coerulea (Alcynaria: Coenothecalia). 475-481. Bell, F. J. 1891. Contributions to our knowledge of the Antipatharian corals. II. On a remarkable Antipathid from the neighbourhood of Mauritius. pp. 91-92.. Transactions of the Zoological Society. Benzoni, F. 2006. Psammocora albopicta sp. nov., a new species of scleractinian coral from the Indo-West Pacific (Scleractinia: Siderastreidae). pp. 49-57. Zootaxa. Benzoni, F. and Pichon, M. 2004. Stylocoeniella nikei n. sp., a new zooxanthellate coral from the Pacific (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia). pp. 147-152. Italian Journal of Zoology. Blainville, H. M. de. 1834. Manuel d'actinologie ou de zoophytologie. Paris Bo, M., Barucca, M., Biscotti, M. A., Canapa, A., Lapian, H. F. N., Olmo, E. & Bavestrello, G. 2009. Description of Pseudocirrhipathes (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Antipathidae), a new genus of whip black corals from the Indo-Pacific. pp. 392-402. Italian Journal of Zoology . Boschma, H. 1948. The species problem in Millepora. pp. 3-115.. Zoologische Verhandelingen. Boschma, H. 1953. Linnaeus's description of the stylasterine coral Errina aspera. pp. 301-310.. I. Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad.Wet. C. Boschma, H. 1960. Gyropora africana, a new stylasterine coral. pp. 423-434.. Proc. -

Cretaceous Bryozoa from the Campanian and Maastrichtian of the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains, United States

Cretaceous Bryozoa from the Campanian and Maastrichtian of the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains, United States Paul D. Taylor & Frank K. McKinney Taylor, P.D. & McKinney, F.K. Cretaceous Bryozoa from the Campanian and Maastrichtian of the Atlan- tic and Gulf Coastal Plains, United States. Scripta Geologica, 132: 1-346, 141 pls, 5 fi gs, 2 tables, Leiden, May 2006. Paul D. Taylor, Department of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK ([email protected]); Frank K. McKinney, Department of Geology, Appalachian State Univer- sity, Boone, North Carolina 28608, U.S.A., and Department of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK ([email protected]). Key words – Bryozoa, Cretaceous, U.S.A., taxonomy The Late Cretaceous bryozoan fauna of North America has been severely neglected in the past. In this preliminary study based on museum material and a limited amount of fi eldwork, we describe a total of 128 Campanian-Maastrichtian bryozoan species from Delaware, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas. Eighty-two of these species are new, as are fi ve (Basslerinella, Pseudoallantopora, Kristerina, Turnerella and Peedeesella) of the 77 genera. One new family, Peedeesellidae, is proposed. Cheilostomes, with 94 species (73 per cent of the total), outnumber cyclostomes, with 34 species (27 percent), a pattern matching that seen elsewhere in the world in coeval deposits. There appear to be very few species (4) in common with the better known bryozoan faunas of the same age from Europe. Although both local and regional diversities are moderately high, most of the Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plain bryozoans are encrusters; erect species are uncommon and are never present in suffi cient density to form bryozoan limestones, in contrast to some Maastrichtian deposits from other regions. -

Evolution of Host Associations in Symbiotic Zoanthidea

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Oceanography Faculty Theses and Department of Marine and Environmental Dissertations Sciences Summer 2010 Evolution of Host Associations in Symbiotic Zoanthidea Timothy D. Swain Florida State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Timothy D. Swain. 2010. Evolution of Host Associations in Symbiotic Zoanthidea. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, . (6) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facetd/6. This Dissertation is brought to you by the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oceanography Faculty Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EVOLUTION OF HOST ASSOCIATIONS IN SYMBIOTIC ZOANTHIDEA By TIMOTHY D. SWAIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Biological Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Timothy D. Swain defended on May 4, 2010. _____________________________ Janie L. Wulff Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ David Thistle University Representative _____________________________ Don R. Levitan Committee Member _____________________________