Inaccurate and False Statements by American Fiddler Mark O'connor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vierteljahrshefte Für Zeitgeschichte Jahrgang 8(1960) Heft 3

VIERTELJAHRSHEFTE FÜR ZEITGESCHICHTE Im Auftrag des Instituts für Zeitgeschichte München herausgegeben von HANS ROTHFELS und THEODOR ESCHENBURG in Verbindung mit Franz Schnabel, Ludwig Dehio, Theodor Schieder, Werner Conze, Karl Dietrich Erdmann und Paul Kluke Schriftleitung: DR. HELMUT KRAUSNICK München 27, Möhlstraße 26 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS AUFSÄTZE H. G. Adler Selbstverwaltung und Widerstand in den Konzentrationslagern der SS . 221 Walter Stubbe In memoriam Albrecht Haushofer . 236 Hans Roos Józef Pilsudski und Charles de Gaulle 257 MISZELLEN Peter Graf Kielmansegg . Die militärisch-politische Tragweite der Hoßbach-Besprechung .... 268 Martin Broszat Zum Streit um den Reichstagsbrand 275 DOKUMENTATION Zur innerpolitischen Lage in Deutschland im Herbst 1929 (Gotthard Jasper) 280 Die Gründung der liberal-demokratischen Partei in der sowjetischen Besatzungszone 1945 (Ekkehart Krippendorff) 290 FORSCHUNGSBERICHT Hans Herzfeld Internationaler Kongreß für Zeit geschichte 310 BIBLIOGRAPHIE 105 Verlag: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH., Stuttgart O, Neckarstr. 121, Tel. 4 36 51. Preis des Einzelheftes DM 7.— = sfr. 8.05; die Bezugsgebühren für das Jahresabonne ment (4 Hefte) DM 24.— = sfr. 26.40 zuzüglich Zustellgebühr. Für Studenten im Abonnement jährlich DM 19.—. Erscheinungsweise: Vierteljährlich. Bestellungen nehmen alle Buchhandlungen und der Verlag entgegen. Geschäftliche Mitteilungen sind nur an den Verlag zu richten. Nachdruck nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung des Verlages gestattet. Das Fotokopieren aus VIERTELJAHRSHEFTE FÜR ZEITGESCHICHTE ist nur mit ausdrück licher Genehmigung des Verlages gestattet. Sie gilt als erteilt, wenn jedes Fotokopierblatt mit einer 10-Pf-Wertmarke versehen wird, die von der Inkassostelle für Fotokopiergebühren, Frankfurt/M., Großer Hirschgraben 17/19, zu beziehen ist. Sonstige Möglichkeiten ergeben sich aus dem Rahmen abkommen zwischen dem Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels und dem Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie vom 14. -

New • Nouveaute • Neuheit

NEW • NOUVEAUTE • NEUHEIT 11/18-(5) Karl Klingler (1879 - 1971) Violin Concerto Viola Sonata Ulf Hoelscher, Violin Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks Volker Schmidt-Gertenbach, Conductor Karl Klingler, Viola Michael Raucheisen, Piano MDG 642 2103-6 UPC-Code: Resourceful History Plentiful Repertoire The Klingler Quartet was regarded as the best string For fifty years Ulf Hoelscher and Volker Schmidt- quartet of its times and as the rightful heir to the Gertenbach have performed together and presented legendary Joachim Quartet. Karl Klingler, the musician seventy works in more than three hundred concerts. The who gave his name to the quartet, had studied with the recording of Klingler’s Violin Concerto was produced Brahms friend Joseph Joachim and had joined his about halfway along their common path and is a teacher’s quartet as a young violist. MDG’s sleuths have document of what even then was a profound shared now found two remarkable historical documents in the understanding of music. archives of the Bavarian Radio that show us Klingler as a composer and as an interpreter: his Violin Concerto with Ulf Hoelscher and the Berlin Philharmonic under Volker further archive –recordings: Schmidt-Gertenbach and the Viola Sonata performed by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Violinkonzert the composer himself along with Michael Raucheisen at Peter Tschaikowsky: Violinkonzert the piano. Pablo de Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen MDG 642 1797-2 Rightful Heir Klingler himself premiered his Violin Concerto with the Gerhard Taschner: Encore ! Berlin Philharmonic in 1907. Already at the age of twenty- Werke von Dvorak, Mussorgsky, two he had joined the orchestra as its concertmaster Beethoven, Brahms u.v.a. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

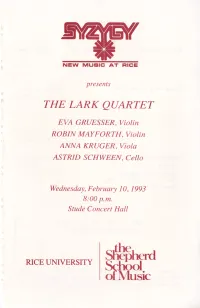

Stir Herd RICE UNNERSITY Sc~Ol of Music PROGRAM

NEW MUSIC AT RICE presents THE LARK QUARTET EVA GRUESSER, Violin ROBIN MAYFORTH, Violin ANNA KRUGER, Viola ASTRID SCHWEEN, Cello Wednesday, February 10, 1993 8:00p.m. Stude Concert Hall stir herd RICE UNNERSITY Sc~ol Of Music PROGRAM Alauda - concert piece for string quartet (1986) Libby Larsen Second String Quartet (1988) Ellsworth M ifburn (b. 1938) INTERMISSION String Quartet ("musica celestis") (1990) Aaron Jay Kernis Flowing (b.1960) musica celestis - Adagio Scherzo - Trio semplice - Scherzo Quasi una Danza Following the concert, everyone is invited to a reception in the Grand Foyer. 1 In consideration of the performers and members of the audience, please check audible paging devices with the ushers and silence audible timepieces. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are prohibited. II. Development: Transition. Four solos which develop Theme 1 ( separ ated by brief contrasting sections). Re-Transition. III. Recapitulation: Theme 1 (shortened and varied). Contrasting Section (Rhythmic Section A) ending in Climax on Theme 1 variant. Theme 2 and Rhythmic Section B developed simultaneously. Closing Section variant. Harmonic Culmination. Coda. The second movement, musica celestis, is inspired by the medieval conception of that phrase which refers to the singing of the angels in heaven in praise of God without end. "The office of singing pleases God if it is performed with an attentive mind, when in this way we imitate the choirs ofangels who are said to sing the Lord's praises without ceasing." (Aurelian ofReome, translated by Barbara Newman) I don't particularly believe in angels but found this to be a potent image that has been reinforced by listening to a good deal ofmedieval music, especially the soaring work of Hildegard of Bingen ( 1098-1179). -

380 XXXIX. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Basel

380 XXXIX. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Basel, [Karlsruhe], [11.] 12. – 15. Juni 1903 Festdirigenten: Hans Huber, Hermann Suter Festchor: Basler Gesangverein, Basler Liedertafel, Reveillechor der Basler Liedertafel Ens.: Orchester der Allgemeinen Musikgesellschaft Basel, verstärkt durch Mitglieder der Meininger Hofkapelle und des Orchestre symphonique de Lausanne sowie hiesige und auswärtige Künstler (110 Musiker) 1. Aufführung: Festvorstellung Karlsruhe, Großhzgl. Hoftheater, Donnerstag, 11. Juni Friedrich Klose: Das Märlein vom Fischer und seiner Frau, Oper 2. Aufführung: I. Konzert [auch: für Soli, Männerchor und Orchester ] Basel, Musiksaal, Freitag, 12. Juni, 19:00 Uhr 1. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze: Sancho, Comédie lyrique Vorspiel für Orchester 2. Friedrich Hegar: Männerchöre a cappella Ch.: Basler Liedertafel a) Das Märchen vom Mummelsee (Ms.) Text: C.A. Schnezler (≡) b) Walpurga op. 31 Text: Carl Spitteler ( ≡) 3. Ernest Bloch: Symphonie cis-Moll (Ms.) 1. 2. Largo 2. 3. Vivace 4. Max von Schillings: Das Hexenlied, mit begleitender Sol.: Ernst von Possart (Rez.) Musik für Orchester op. 15 Text: Ernst von Wildenbruch 5. Waldemar Pahnke: Concert für Violine und Orchester c- Sol.: Henri Marteau (V.) Moll (Ms.) 1. Moderato con moto 2. Allegro vivace ---- 6. Hans Huber: Caenis (die Verwandlung), für Männerchor, Sol.: Maria Cäcilia Philippi (A) Altsolo und Orchester op. 101 Ch.: Basler Liedertafel Text: Joseph Victor Widmann, nach einer antiken Sage (≡) 7. Gesänge für Bariton mit Orchester Sol.: Richard Koennecke (Bar.) a) Klaus Pringsheim: Venedig Text: Friedrich Nietzsche (≡) Oskar C. Posa: b) Tod in Aehren Text: Detlev von Liliencron (≡) c) „Mit Trommeln und Pfeifen“ (Ms.) Text: Detlev von Liliencron (≡) 8. Ernst Boehe: Aus Odysseus Fahrten, 4 Episoden für grosses Orchester gesetzt op. -

ESA Newsletter 2004

TI{E Yolume 24 Spring 2004 EUROPEAN SU ZUKI TEACI{ERS' NEWSLETTER r.) ts . rt,:ilrlilr:ii;i: .,:.-===,,::,,,,. rLL ; : ,,,,, =Of f iqialPublicätioö:löflfi g,p;rri:iffi j,ji European Suzuki AssoCiation r' Ltd (ESA) . : t: :', ',', I fft;,,...E§§lS: i,g..,,to,..,, l$@l$.' vShi&iähi:.:::§uäü,kili1iiiiil, FEoacli::=;=t e&§atio€ Tlie .* ,.;,a*ea is Ew;ü, *rä &üddL Prrt "porti"" and Ä&ica, as decided by the Intemationd M §u ħs ri+n rrhich,iheltSÄ,,iii::*,, membeil, Th.,i".*ers= äd| ;, Suzuki teaching :is 5*u* t.rcher - i T.4initt Ti,,trii i.$#6li+ 4, ffid nnd lang ifu,: *-the ESA's Teacher Tlaining and Examination ,". M riiirßxi ,I{4 .:. iiiii Saryki Violin - Ingrid Haluorsen, Noruay aged 4 &om thi natiqnal assasiadons and the fSa omcaj. Examinationi ,r. *,.U ,t *o" kt§l§.,1ädi &a. TABI.E OF CONTENTS E=@Pt*t4Siriii[rbiiiiiffi§i]rü.) :;:::,(}f ,i..iSr:iii:ir,, Lti International Instrument Committees 3 Fbi rncre. ::.=fifo ttioa äb-lö§tj::äetä§, European Suzuki Teaching Development Trust: A report 4 venues .1 il'äsffiop f*l1ghii e**e --contäCt üe organisers in each courlbry, Shinichi Suzuki: A Short Biography Enid Vood 5 txt'd1n, ä{t*är @ i:$fitr§,,ioffi.ilii1i, ESA Neuzs 5-6 Chairperson: T i rn e for I n spira ti o n; BSI' s European Con ference at Greenwich 6 l News from ESA's National Associations 7, 13-14 ESA Information 8-9 Dr. Birte Kelly- ESA, Stour House, The Street, East Bergholt, E SA Teache rT ratner f Examiners 9-10 Colchester, CO? 6. -

Biographic Sketch and Work Catalogue

Biographic Sketch and Work Catalogue Jörg Widmann was born on 19 June 1973 in Munich, the son of a physicist and a teacher and textile artist. His younger sister is the violinist and violin professor Carolin Widmann. He began clarinet lessons at age 7, completing his education with Gerd Starke at the Munich Music Academy and with Charles Neidich at the Juilliard School in New York. His studies in composition began with Kay Westermann when he was 11 years old; they were continued in 1994-1996 with Wilfried Hiller and Hans Werner Henze and concluded in 1997-1999 with Heiner Goebbels and Wolfgang Rihm. Since the fall of 2001, Widmann has been teaching as professor of clarinet at the Musikhochschule Freiburg; eight years later the same institution additionally named him professor of composition. As a clarinetist, Widmann champions chamber music. He concertizes regularly with partners like the oboist Heinz Holliger, the violists Tabea Zimmermann and Kim Kashkashian, the pianists András Schiff and Hélène Grimaud, and the soprano Christine Schäfer. Moreover, he is celebrated at home and abroad as a soloist in clarinet concertos, and several contem- porary composers have dedicated works for or with clarinet to him. Thus he premiered Wolfgang Rihm’s Music for Clarinet and Orchestra in 1999, Aribert Reimann’s Cantus in 2006, Heinz Holliger’s Rechant in 2009, and Peter Ruzicka’s Three Pieces for Clarinet Solo in 2012. In the course of the years 1993 to 2013, i.e., the two decades between his twentieth and his fortieth birthdays, Widmann has written more than eighty compositions. -

Cultural Translation in Two Directions: the Uzs Uki Method in Japan and Germany Margaret Mehl University of Copenhagen

Research & Issues in Music Education Volume 7 Number 1 Research & Issues in Music Education, v.7, Article 2 2009 2009 Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The uzS uki Method in Japan and Germany Margaret Mehl University of Copenhagen Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.stthomas.edu/rime Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Mehl, Margaret (2009) "Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The uzS uki Method in Japan and Germany," Research & Issues in Music Education: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: http://ir.stthomas.edu/rime/vol7/iss1/2 This Featured Articles is brought to you for free and open access by UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research & Issues in Music Education by an authorized editor of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mehl: Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The Suzuki Method in Japa Abstract Cultural Translation in Two Directions: The Suzuki Method in Japan and Germany The Suzuki Method represents a significant contribution by a Japanese, Suzuki Shin'ichi (1898- 1998), to the teaching of musical instruments worldwide. Western observers often represent the method as "Japanese," although it could be called "Western" with equal justification. Suzuki left no detailed description of his method. Consequently, it is open to multiple interpretations. Its application, whether in Japan or elsewhere, represents an act of translation with its adaptation to local conditions involving creative processes rather than mere deviations from a supposedly fixed original. To illustrate the importance of historical context, the author discusses Suzuki's life and work, sheds new light on the significance of his studies in Germany in the 1920s, and explains the method's success in Japan and abroad by examining local and historical circumstances. -

Suzuki Program Parent Handbook

SUZUKI PROGRAM PARENT HANDBOOK 2013 Music Institute of Chicago “Each second we live is a new and unique moment of the universe, a moment that never was before and never will be again. And what do we teach our children in school? We teach them that two and two make four and that Paris is the capital of France. When will we also teach them what they are? We should say to each of them: Do you know what you are? You are a marvel. You are unique. In all the world there is no other child exactly like you. In the millions of years that have passed there has never been a child like you. And look at your body – what a wonder it is! Your legs, your arms, your cunning fingers, the way you move! You may become a Shakespeare, a Michelangelo, a Beethoven. You have the capacity for anything. Yes, you are a marvel. And when you grow up, can you then harm another who is, like you, a marvel? You must cherish one another. You must all work – we must all work to make this world worthy of its children.” Pablo Casals TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT IS THE SUZUKI METHOD? ........................................................................................ 1 THE PARENT’S ROLE ............................................................................................................... 4 AGGRAVATING ANTICS.......................................................................................................... 6 HOW AND WHY TO LISTEN ................................................................................................... 7 PRACTICING .............................................................................................................................. -

STRING PLAYERS by David Milsom of STRING PLAYERS CONTENTS

STRING PLAYERS by David Milsom of STRING PLAYERS CONTENTS Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................5 CD Track Lists ...................................................................................................................6 Bonus Area Website .................................................................................................18 Preface ..............................................................................................................................20 BIOGRAPHIES ................................................................................................................27 Credits ............................................................................................................................. 664 About the Author .................................................................................................... 665 3 of STRING PLAYERS of STRING PLAYERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to the editorial team at Naxos for their unfailing patience and humour in a lengthy and, at times, frustrating project – my particular gratitude goes to Genevieve Helsby and Pamela Scray!eld. I would also like to thank all those who have given me the bene!t of their wisdom and expertise including, notably, George Kennaway, David Patmore, Tully Potter and Jonathan Summers – all of whom have provided elusive missing information and a considerable amount of helpful advice – as well as Robert Webb, who gave me a useful boost in terms of research -

Einstein's Friend, Walther Rathenau

III. Walther Rathenau: Behind the Curtain of History Einstein’s Friend, Walther Rathenau: The Agapic Personality in Politics and Diplomacy PART ONE OF TWO PARTS by Judy Hodgkiss June 2012—The following, He thought of himself foremost excerpted from a two-part arti- as a writer, a philosopher, a cle in the German newspaper, poet, an artist, and a musician. Neue Solidarität, is intended as Therefore, when he devised a case study into the unique his various policies, his first personality type capable of consideration was never what calm, creative leadership, as others might consider to be demonstrated in the atmo- “practical”; he saw his fight sphere of panic in 1920’s against the British Empire as Weimar Germany, or, as will primarily a cultural fight, a be needed, in the panic soon to battle for the “soul” of the come upon us, in the existen- German nation. tial crisis of today. Rathenau served as political advisor—officially and unoffi- ON JUNE 24, 2012 we com- cially—to almost all of the turn- memorate the 90th anniversary of-the-century German govern- of the assassination of the ments: from the pre-war reign of German Foreign Minister Wal- Kaiser Wilhelm II and his cabi- ther Rathenau, a singular figure net; through the war-time emer- in the industrialization and the gency governments and the cha- Bundesarchiv/Bild political leadership of the Walter Rathenau, August 1, 1921. otic coups and counter-coups of German nation at the beginning the demobilization; then in the of the 20th Century. His was a personality perfectly post-war Weimar Republic, until his death in 1922.