Disfiguring Socratic Irony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Children of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre. Tony Earnest Medlin Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Medlin, Tony Earnest, "The hiC ldren of Molemo: an Analysis of Johnny Simons' Performance Genealogy and Iconography at the Hip Pocket Theatre." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7281. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7281 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Eiron and the Alazon in Edward Albee's the Zoo Story (1958), Le Roi Jones's Dutchman (1964) and Adrienne Kennedy's

Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Mouloud Mammeri University of Tizi-Ouzou Faculty of Arts and Languages Department of English A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Master’s Degree in English Option: Drama Arts Subject: The Eiron and the Alazon in Edward Albee’s the Zoo Story (1958), Le Roi Jones’s Dutchman (1964) and Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro (1969) Presented by: - OULAGHA Zakia - TOUIL Elyes Panel of Examiners: -Dr.Siber Mouloud ,M.C.A., UMMTO, Chairman. -Dr. Gariti Mohamed, M.C.A., UMMTO, Supervisor. -Abdeli Fatima,M.A.A., UMMTO, Examiner. Academic Year: 2016-2017 Abstract This research paper has studied the elements underlying the absurdity of communication between the characters in Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story, Le Roi Jones’s Dutchman and Adrienne Kennedy’s Funnyhouse of a Negro. This issue has been addressed through three major phases. First, the focus has been placed upon the socio-economic and racial injustices in the American society during the 1950s and 1960s. Second, as a direct consequence of the socio-economic disparity, the alienation experienced by the plays’ central characters has been analyzed in the light existentialism. Third, the very absurdity of the characters’ interaction has been interpreted in terms of the characters’ ironic pursuit for communication. Such ironic interaction has therefore been tackled from a mythical perspective calling forth Northrop Frye’s theory of archetypes, particularly the mythos of satire and irony. Hence, it has been concluded that the characters’ failed communication is brought about by their ironic attack of their interlocutors’ fake personas. -

Celebrity and Authorial Integrity in the Films of Woody Men %Y

CELEBRITY AND AUTHORIAL INTEGRITY IN THE FILMS OF WOODY ALLEN BY FAYE MCINTYRE A Thesis Submitted to the Facul@ of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba (c) January, 200 1 National Library BibIiothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON Ki A ON4 Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Canada Canada rour rïk vom rbw~ Our fi& Notre rtifBrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lïbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts fÏom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES *f *f * COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE Celebrity and Authorial Integrity in the Films of Woody Men %Y Faye McIntyre A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulNlment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy FAYE MCINTYRE O 2001 Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to Iend or seU copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis/practicum and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. -

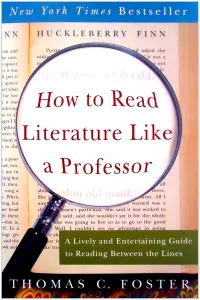

How to Read Literature Like a Professor Notes

How to Read Literature Like a Professor (Thomas C. Foster) Notes Introduction Archetypes: Faustian deal with the devil (i.e. trade soul for something he/she wants) Spring (i.e. youth, promise, rebirth, renewal, fertility) Comedic traits: tragic downfall is threatened but avoided hero wrestles with his/her own demons and comes out victorious What do I look for in literature? - A set of patterns - Interpretive options (readers draw their own conclusions but must be able to support it) - Details ALL feed the major theme - What causes specific events in the story? - Resemblance to earlier works - Characters’ resemblance to other works - Symbol - Pattern(s) Works: A Raisin in the Sun, Dr. Faustus, “The Devil and Daniel Webster”, Damn Yankees, Beowulf Chapter 1: The Quest The Quest: key details 1. a quester (i.e. the person on the quest) 2. a destination 3. a stated purpose 4. challenges that must be faced during on the path to the destination 5. a reason for the quester to go to the destination (cannot be wholly metaphorical) The motivation for the quest is implicit- the stated reason for going on the journey is never the real reason for going The real reason for ANY quest: self-knowledge Works: The Crying of Lot 49 Chapter 2: Acts of Communion Major rule: whenever characters eat or drink together, it’s communion! Pomerantz 1 Communion: key details 1. sharing and peace 2. not always holy 3. personal activity/shared experience 4. indicates how characters are getting along 5. communion enables characters to overcome some kind of internal obstacle Communion scenes often force/enable reader to empathize with character(s) Meal/communion= life, mortality Universal truth: We all eat to live, we all die. -

Toward a Female Clown Practice: Transgression, Archetype and Myth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Plymouth Electronic Archive and Research Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. 0 Toward a Female Clown Practice: Transgression, Archetype and Myth By Maggie (Margaret) Irving A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities and Performing Arts Faculty of Arts Date: 26th September 2012 1 Maggie (Margaret) Irving Toward a Female Clown Practice: Transgression, Archetype and Myth Women who learn to clown within Western contemporary theatre and performance training lack recognizably female exemplars of this popular art form. This practice-as- research thesis analyses my past and present clowning experiences in order to create an understanding of a woman-centered clown practice which allows for the expression of material bodies and lived experiences. It offers a feminist perspective on Jacques Lecoq’s pedagogy, which revolves around a notion of an ‘inner clown’ and is prevalent in contemporary UK clown training and practice. The thesis draws on both the avant- garde and numerous clown types and archetypes, in order to understand clowning as a genre revealed through a range of unsocialised behaviours. It does not differentiate necessarily between clowning by men and women but suggests a re-think and reconfiguration to incorporate a wide range of values and thought processes as a means of introduction to a wider audience. -

The Postmodern Theatre Clown Ashley Tobias

The Postmodern Theatre Clown Ashley Tobias During the postmodern era the status of the clown underwent significant change as the figure shifted from social, artistic and academic marginality to centre-stage. Indeed, the clown became integrally enmeshed with the perceptions, attitudes and operations of the phenomenon known as postmodernism. Inexplicably, the clown type I term the “postmodern theatre clown” has been virtually overlooked by academic research.1 In this paper, I initially outline the fundamental approach to be followed when seeking to define the postmodern theatre clown. Subsequently, I demonstrate the approach by focusing on two outstanding exemplars of the type and illustrate by referring to specific scenes from their performances and texts. The term “clown,” when used generically, refers to a very extensive group of figures going back in time to the most primitive of tribal existence but equally at home in contemporary, technologically advanced societies. A fond figure of imaginative fiction, a pivotal participant in social ritual, or a very real person in the realm of historical fact, clowns reside in many worlds, often straddling the boundaries of fact, fiction, ritual, art and reality. This group is comprised of many and varied types known as: fool, court-jester, buffoon, theatre clown, mime-clown, silent film clown, alazon, eiron, bomolochos, commedia dell’arte clown, street clown, circus clown and ritual clown. In addition to these terms used to label the specific types, clowns are also referred to as: comedians, comics, drolls, farceurs, humorists, Harlequins, jokers, mimes, mummers, pranksters, tricksters, wags and wits. Often there is neither absolute consensus on the exact referents of the various neither terms nor full agreement on their precise usage. -

How to Read Literature Like a Professor: a Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines

How to Read Literature Like a Professor: A Lively and Entertaining Guide to Reading Between the Lines By THOMAS C. FOSTER Contents INTRODUCTION: How’d He Do That? 1. Every Trip Is a Quest (Except When It’s Not) 2. Nice to Eat with You: Acts of Communion 3. Nice to Eat You: Acts of Vampires 4. If It’s Square, It’s a Sonnet 5. Now, Where Have I Seen Her Before? 6. When in Doubt, It’s from Shakespeare... 7. ...Or the Bible 8. Hanseldee and Greteldum 9. It’s Greek to Me 10. It’s More Than Just Rain or Snow INTERLUDE Does He Mean That? 11. ...More Than It’s Gonna Hurt You: Concerning Violence 12. Is That a Symbol? 13. It’s All Political 14. Yes, She’s a Christ Figure, Too 15. Flights of Fancy 16. It’s All About Sex... 17. ...Except Sex 18. If She Comes Up, It’s Baptism 19. Geography Matters... 20. ...So Does Season INTERLUDE One Story 21. Marked for Greatness 22. He’s Blind for a Reason, You Know 23. It’s Never Just Heart Disease... 24. ...And Rarely Just Illness 25. Don’t Read with Your Eyes 26. Is He Serious? And Other Ironies 27. A Test Case ENVOI APPENDIX Reading List Introduction: How’d He Do That? MR. LINDNER? THAT MILQUETOAST? Right. Mr. Lindner the milquetoast. So what did you think the devil would look like? If he were red with a tail, horns, and cloven hooves, any fool could say no. The class and I are discussing Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959), one of the great plays of the American theater. -

The Braggart Soldier: an Archetypal Character Found in "Sunday in the Park with George"

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 The Braggart Soldier: An Archetypal Character Found In "Sunday In The Park With George" Paul Gebb University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Gebb, Paul, "The Braggart Soldier: An Archetypal Character Found In "Sunday In The Park With George"" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3172. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3172 THE BRAGGART SOLDIER: AN ARCHETYPAL CHARACTER FOUND IN “SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE” By PAUL GEBB B.M. James Madison University, 2002 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2007 © 2007 Paul Gebb ii ABSTRACT In preparation for performance, an actor must develop an understanding for the character they portray. A character must be thoroughly researched to adequately enrich the performance of the actor. In preparation for the role of the “Soldier” in the production, Sunday in the Park with George, it is important to examine the evolution of the “Braggart Soldier” archetypal character throughout the historical literary canon. -

Dal Miles Gloriosus Al Vantone Di Pasolini

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI FOGGIA DIPARTIMENTO DI TRADIZIONE E FORTUNA DELL’ANTICO DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN: SCIENZE DELL'ANTICHITÀ CLASSICA E CRISTIANA ANTICA TARDOANTICO E MEDIEVALE: STORIA DELLA TRADIZIONE E DELLA RICEZIONE CICLO: XXIV DAL MILES GLORIOSUS AL VANTONE DI PASOLINI TESI PRESENTATA DA: ROSA CICOLELLA TUTORS: PROF. GIOVANNI CIPRIANI COORDINATORE DEL DOTTORATO: PROF. MARCELLO MARIN ANNI ACCADEMICI 2009-2013 Sommario INTRODUZIONE .................................................................................................... 3 CAP.1 LA FORTUNA DEL MILES ....................................................................... 4 1.1La vita di Plauto secondo le notizie degli antichi e dei moderni ......................... 4 1.2 Dai Greci a Plauto ............................................................................................. 7 1.3 La commedia plautina ...................................................................................... 13 1.4 Il problema della maschera .............................................................................. 21 1.5 Dall’acrostico alla fabula ................................................................................. 26 1.6 La maschera del Miles Gloriosus .................................................................... 30 1.7 Guerriero ridicolo o Miles Gloriosus? Un excursus dalle origini al 1600 ........ 38 CAP. 2 LA CONTAMINATIO: DA TERENZIO A CORNEILLE ........................ 46 2.1Elementi plautini in Terenzio ........................................................................... -

Proquest Dissertations

001565 SHAKESPEARE'S CLOWN-FOOLS REVISITED WITH AN ORIENTAL ESCORT: A RECONSIDERATION OF FALSTAFF, LEAR'S FOOL, CLEOPATRA'S CLOWN, AND AN EXAMINATION IN THIS LIGHT OF A CLOWN-FOOL OF SANSKRIT DRAMA by Ratna Ray Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature. 'BRfii Ottawa, Ontario, 1970 UMI Number: DC53647 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53647 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CURRICULUM STUDIORUM Ratna Ray was born in Shillong, India, on July 22, 1936. She received the Master of Arts degree from the University of Calcutta in 1957. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the diligent super vision and profound direction of Dr. Richard N. Pollard of the Department of English. Words are insufficient to convey my immeasurable indebtedness to this highly esteemed teacher. Hence, as a token of my sincere appreciation I dedicate this thesis with devotion and reverence to Dr. -

AN INTRODUCTION to PLAUTUS THROUGH SCENES Selected And

AN INTRODUCTION TO PLAUTUS THROUGH SCENES Selected and Translated by Richard F. Hardin ‘Title page for Titus Maccius Plautus, Comoediae Superstites XX, 1652’ Lowijs Elzevier (publisher) Netherlands (Amsterdam); 1652 - The Rijksmuseum © Copyright 2021, Richard F. Hardin, All Rights Reserved. Please direct enquiries for commercial re-use to [email protected] Published by Poetry in Translation (https://poetryintranslation.com) This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply: https://poetryintranslation.com/Admin/Copyright.php 1 Preface This collection celebrates a comic artist who left twenty plays written during the decades on either side of 200 B.C. He spun his work from Greek comedies, “New Comedies” bearing his own unique stamp.1 In Rome the forerunners of such plays, existing a generation before Plautus, were called fabulae palliatae, comedies in which actors wore the Greek pallium or cloak. These first situation comedies, Greek then Roman, were called New Comedies, in contrast with the more loosely plotted Old Comedies, surviving in the plays of Aristophanes. The jokes, characters, and plots that Plautus and his successor Terence left have continued to influence comedy from the Renaissance even to the present. Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, Taming of the Shrew, Merry Wives of Windsor, and The Tempest are partly based on Menaechmi, Amphitruo, Mostellaria, Casina, and Rudens; Molière’s L’Avare (The Miser), on Aulularia; Gelbart and Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, on Pseudolus, Miles Gloriosus, Casina, and Mostellaria; David Williamson’s Flatfoot (2004) on Miles Gloriosus; the Capitano in Commedia dell’Arte, Shakespeare’s Falstaff, and Jonson’s Bobadill all inherit traits of Plautus’s braggart soldiers. -

Matthew W. Dickie, Magic and Magicians in the Greco-Roman World

MAGIC AND MAGICIANS IN THE GRECO- ROMAN WORLD This absorbing work assembles an extraordinary range of evidence for the existence of sorcerers and sorceresses in the ancient world, and addresses the question of their identities and social origins. From Greece in the fifth century BC, through Rome and Italy, to the Christian Roman Empire as far as the late seventh century AD, Professor Dickie shows the development of the concept of magic and the social and legal constraints placed on those seen as magicians. The book provides a fascinating insight into the inaccessible margins of Greco- Roman life, exploring a world of wandering holy men and women, conjurors and wonder-workers, prostitutes, procuresses, charioteers and theatrical performers. Compelling for its clarity and detail, this study is an indispensable resource for the study of ancient magic and society. Matthew W.Dickie teaches at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He has written on envy and the Evil Eye, on the learned magician, on ancient erotic magic, and on the interpretation of ancient magical texts. MAGIC AND MAGICIANS IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD Matthew W.Dickie LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in hardback 2001 by Routledge First published in paperback 2003 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 2001, 2003 Matthew W.Dickie All rights reserved.