Historical Studies Vol 74 Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ATLANTIC REGION BISHOPS a Meeting of the Atlantic Region

THE ATLANTIC REGION BISHOPS A meeting of the Atlantic Region bishops was held on Prince Edward Island, September 15, 16, and 17. It was also a “first” in the history of our meetings. Let us recall that from 1829 to 1842, we were part of the diocese of Charlottetown which today has a Catholic population of 61,000 out of a total population of 135,000. JUBILEE YEAR As it is with the Church universal, we too are always turned towards Jesus, the Christ, the Messiah “yesterday, today, and forever”. We remember the three great requirements of a jubilee year: the respect of every human being, a sharing of the wealth, and protection of our environment. It is in this context that the bishops’ agenda of some thirty-odd items can be viewed. The bishops and the administrator of the twelve Atlantic region dioceses are very much aware of the jubilee requirements, and they want to experience this exceptional grace to the fullest by opening even wider the doors to Christ the Saviour and by making of their ministry a daily pilgrimage to their brothers and sisters. PASTORS FOR YOU It is significant that our meeting ended with a joyous concelebration in St. Augustin Church, Rustico, the oldest Catholic church on the Island, birthplace of the late Archbishop Cornelius O’Brien of Halifax and the late Cardinal James McGuigan, Archbishop of Toronto. About a pastor’s pastoral charge, Saint Augustin wrote: “I must distinguish carefully between two aspects of the role the Lord has given me, a role that demands a dangerous accountability, a role based on the Lord’s greatness rather than on my own merit. -

Ted Schmidt: Teacher Witness to Faith

Ted Schmidt: Teacher Witness to Faith TED SCHMIDT is the the former editor of the Catholic New Times. As well he is the author of Shabbes Goy: a Catholic Boyhood on a Jewish street in a Protestant City (2001) and Journeys to the Heart of Catholicism 2008 and Never Neutral: A Teaching Life (2012) He attended St Peter’s elementary school, St Michael’s College High School and the St Michael’s College, University of Toronto majoring in Classics and English. He studied scripture at Corpus Christi College under Fr Hubert Richards. Ted was a lifelong high school teacher in both the public and Catholic system. He spent 18 years teaching religion at Neil McNeil High school and 10 years at Bishop Marrocco-Thomas Merton. In a lifetime of teaching he has been honoured by religion teachers and colleagues at large. In 1991 he received the Ontario English Teachers' Award of Merit, the highest distinction the association grants. In 1998 he received the Glorya Nanne award for his writing on Catholic education. In 2002 he received the Social Justice Award from the Toronto Secondary Catholic Teachers Association. In 2006 the Ontario Teachers’ Federation honoured him with the Greer Memorial Award for his “outstanding commitment to publicly funded education.” A pioneer in Holocaust studies, he was the first teacher in Canada to systematically teach the Holocaust (1968) and has done several workshops for the Holocaust Remembrance committee. In 1993 he co-authored the Ministry of Education OAC course on Philosophy. For 30 years Ted has taught OECTA courses on scripture, social ethics and the sacraments as well as doing several series on biblical themes in parishes. -

ARCHIVES DE LA SACR£E CONGR£GATION DE LA PROPAGANDE Instrument De Recherche N° 1186 Partie V, Vol

ARCHIVES PUBLIQUES DU CANADA DIVISION DES MANUSCRITS VATICAN: ARCHIVES DE LA SACR£E CONGR£GATION DE LA PROPAGANDE Instrument de recherche n° 1186 Partie V, Vol. 1 INDEX Prepare par Monique Benoit pour le Centre de recherche en histoire religieuse du Canada de l'universite Saint-Paul et le Centre academique canadien en Italie, grace a une subvention du Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines du Canada. 1986 e MONIQUE BENOIT INVENTAIRE DES PRINCIPALES SERIES DE DOCUMENTS INTERESSANT LE CANADA, SOUS LE PONTIFICAT DE LEON XIII (1878-1903), DANS LES ARCHlVESJD~ LA SACREE CONGREGATION 'DE PROPAGANDA FIDE' A ROME: ACTA (1878-1903) SOCG (1878-1892) SC (1878-1892) N.S. (1893-1903) VOL I: INDEX e. 2 • TABLE DES MATIERES VOL. I Introduction generale 3 Abreviations et symboles 10 Taeleau I - Repartition des dioceses en 1878 12 Tableau II - Repartition des dioceses en 1903 13 Index 14 VOL. II Table des matieres du vol. II 2 Introduction a la serie ACTA 3 Inventaire de la ser~e ACTA 31 Introduction a la s.erie SOCG 57 Inventaire de la serie SOCG 58 Introduction a la serie SC 128 Inventaire de la serie SC 130 VOL. III Table des matieres du vol. III 536 Introduction.a la serie N.S. 537 Inventaire de lao serie N. S. 539 • /' 3 • INTRODUCTION GENERALE Fondee en 1622 pour diriger l'oeuvre missionnaire, coordonner la distribution des ressources humaines et financieres, promouvoir le clerge autochtone, la Sacree congregation pour la propagation de la foi est tres presente au Canada a la fin du e • _ I XIX siecle, alors meme que l'Eglise canadienne s achemine vers la maturite. -

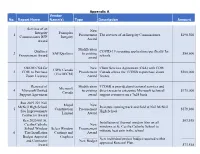

Appendix a Vendor No

Appendix A Vendor No. Report Name Name(s) Type Description Amount Services of an New Integrity Principles 1 Procurement The services of an Integrity Commissioner. $190,500 Commissioner RFP Integrity Award Award Modification Qualtrics COVID-19 screening application specifically for 2 SAP/Qualtrics to existing $80,600 Procurement Award schools award OECM CSA for New Client Services Agreement (CSA) with CDW CDW Canada 3 CDW to Purchase Procurement Canada allows the TCDSB to purchase Zoom $300,000 (Via OECM) Zoom Licenses Award license Renewal of Modification TCDSB is provided professional services and Microsoft 4 Microsoft Unified to existing direct access to enterprise Microsoft technical $175,000 Canada Support Agreement award support resources on a 7x24 basis Ren 2019 221 Neil Mopal New McNeil High School Reinstate running track and field at Neil McNeil 5 Construction Procurement $579,860 Site Improvements High School Limited Award Contractor Award Ren 2020 001 St. $63,518 Installation of thermal window film on all Cecilia Catholic New windows at St. Cecilia Catholic School to School Window Select Window Procurement mitigate heat gain in the school 6 Tint Installation Coatings and Award _______________________ Budget Approval Graphics ________ _______ New individual project budget required within and Contractor New Budget approved Renewal Plan. Award $73,518 Appendix A Vendor No. Report Name Name(s) Type Description Amount Ren 2020 002 Immaculate New Energy conservation measures including Conception Catholic Procurement Upgrades and Retrocommissioning of HVAC $330,021 School Upgrades Active Award System at Immaculate Conception 7 and Mechanical ___________ ________________________________ _______ Retrocommissioning Budget Budget Increase and Scope Increase $377,899 of HVAC System - Increase Contractor Award Ren 2020 003 St. -

Director's Bulletin

Validating our Mission/Vision May 5, 2008 IFITH Subjects: 1. COMPASSION – VIRTUE FOR THE MONTH OF MAY 2. LAUNCH OF WE REMEMBER, WE BELIEVE--repeat T 3. SAINTS OF THE TORONTO CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD H DIRECTOR’S E 4. RESPECT FOR LIFE WEEK BULLETIN 5. 2008/2009 CRIMINAL OFFENCE DECLARATION 2007-2008 6. CUPE 1280 DUTY ROSTER--repeat 7. HEAD CARETAKER PRE-QUALIFYING TEST--repeat In a school community 8. MAY IS SPEECH, LANGUAGE AND HEARING MONTH formed by Catholic 9. INTERMEDIATE W5H RESULTS beliefs and traditions, 10. AWARDS, SCHOLARSHIPS, BURSARIES & CONTESTS our Mission is to - Jean Lumb Awards educate students - MEA Bursary Award to their full potential 11. SCHOOL ANNIVERSARIES, OFFICIAL OPENING & BLESSINGS - Neil McNeil’s Golden Jubilee Events--repeat - Marshal McLuhan’s 10th Anniversary--repeat th - St. Gabriel Lalemant’s 25 Anniversary--repeat - Monsignor Percy Johnson’s Official Opening & Solemn Blessing Compassion - Father Henry Carr’s Official Opening & Solemn Blessing Virtue for the 12 EVENT NOTICES Month of May - Computer Basic Training for Parents - Culture Jam at Notre Dame - DIGITAL Showcase at St. Basil - St. Mary’s The Outsiders Compassion - Bishop Marrocco/Thomas Merton’s Time for sale - Staff Arts’ Seussical--repeat connects us with others… it is understanding 13. SHARING OUR GOOD NEWS and caring - Loretto College School - St. Marcellus Catholic School for those in need. - Holy Family Catholic School - Notre Dame High School - Neil McNeil High School - All Saints Catholic School, Bishop Allen Academy & Father Henry Carr Catholic Secondary School - St. Basil-the-Great College School Faith in Your Child - Father John Redmond Catholic Secondary School - Senator O’Connor College School - St. -

Companions on the Journey

The Catholic Women’s League of Canada 1990-2005 companions on the journey Sheila Ross The Catholic Women’s League of Canada C-702 Scotland Avenue Winnipeg, MB R3M 1X5 Tel: (888) 656-4040 Fax: (888) 831-9507 Website: www.cwl.ca E-mail: [email protected] The Catholic Women’s League of Canada 1990-2005: companions on the journey Contents Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 1990: Woman: Sharing in the Life and Mission of the Church.................. 8 1991: Parish: A Family of the Local Church: Part 1 ................................. 16 1992: Parish: A Family of the Local Church: Part II ................................. 23 1993: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada – rooted in gospel values: Part I........................................................................................ 30 1994: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada – rooted in gospel values: Part II ....................................................................................... 36 1995: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − calling its members to holiness............................................................................................ 42 1996: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − through service to the people of God: Part I ................................................................... 47 1997: The Catholic Women’s League of Canada − through service to the people of God: Part II .................................................................. 54 1998: People of God -

Diocese of London Series (F01-S128)

Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada Finding Aid - Diocese of London series (F01-S128) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.5.4 Printed: August 10, 2020 Language of description: English Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada 485 Windermere Road P.O. Box 487 London Ontario Canada N6A 4X3 Telephone: 519-432-3781 ext. 404 Fax: 519- 432-8557 Email: [email protected] https://www.csjcanada.org/ http://www.archeion.ca/index.php/diocese-of-london-series Diocese of London series Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 5 F01-S128--01, Bishop Fallon (1910-1953) ................................................................................................. -

The Ministry

THE MINISTRY 67 are chosen by the Prime Minister; each of them generally assumes charge of one of the various departments of the government, although one Minister may hold two portfolios at the same time, while other members may be without portfolio. The twelfth Ministry consisted on Sept. 30, 1925, of 21 members; 4 of them were without portfolio, while 3 others, including the Prime Minister, were in charge of two or more departments. The Prime Ministers since Confederation and their dates of office, together with the members of the twelfth Ministry, as on Sept. 30, 1925, are given in Table 2. 2.—Ministries since Confederation. NOTE.—Acomplete list of the members of Dominion Ministries from Confederation to 1913 appeared in the Year Book of 1912, pp. 422-429. A list of the members of Dominion Ministries from 1911 to 1921 appeared in the Year Book of 1920, pp. 651-653. 1. Rt. Hon. Sir John A. Macdonald, Premier. From July 1,1867 to Nov. 6,1873. 2. Hon. Alexander.Mackenzie, Premier. From Nov. 7,1873 to Oct. 16,1878. 3. Rt. Hon. Sir John A. Macdonald, Premier. From Oct. 17, 1878 to June 6,1891. 4. Hon. Sir John J. C. Abbott, Premier. From June 16,1891 to Dec. 5,1892. 5. Hon. Sir John S. D. Thompson, Premier. From Dec. 5, 1892 to Dec. 12, 1894. 6. Hon. Sir Mackenzie Bowell, Premier. From Dec. 21, 1894 to April 27, 1896. 7. Hon. Sir Charles Tupper, Premier. From May 1,1896 to July 8,1896. 8. Rt. Hon. Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Premier. -

The Politics of Liquor in British Columbia 1320-1928

bhtbwl Library 01-ue nationale of Canada du Canada . .- Acrpnsrtmorrsand Directiton des acquisitions et BiMbgraphi Services Branch des services bibliographiques NOTICE AVlS The quality of this microform is La qualite de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the depend grandement de la qualit6 quality of the original thesis de la these soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualit6 - ensure the highest quality of superieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the cornmuniquer avec I'universite degree. qui a confer6 le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualit6 d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser a pages were typed with a poor desirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont 6te university sent us an inferior dactylographiees B I'aide d'un photocopy. ruban us6 su si I'universite nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de - qualit6 infbrieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, mOme partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, a la Loi canadienne sur le droit R-S.C. 1970, c. C-30, and d'auteur, SHC 1970, c. C-30, et subsequent amendments. ses arnendemrnts subsequents. THE POLITICS OF LIQUOR 1 N BRITISH COLUMBIA: 1920 - 1928 by RUTH PRICE B.G.S., Simon Fraser Universm, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science @ ~uthPrice SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1991 All rights reserved. -

Annales Missiologici Posnanienses” (Paweł Zając) Wydział Teologiczny Uniwersytetu Im

AANNALESNNALES MMISSIOLOGICIISSIOLOGICI PPOSNANIENSESOSNANIENSES Pierwszy tom niniejszego wydawnictwa ukazał się w roku 1928 pod tytułem: „Roczniki Związku Akademickich Kół Misyjnych. Czasopismo Roczne Po- święcone Zagadnieniom Misjologii” (t. 1-4). Od tomu piątego tytuł został zmieniony na „Annales Missiologicae. Roczniki Misjologiczne” i pod tym tytułem ukazało się kolejnych sześć tomów (t. 5-10, ostatni w roku 1938). W roku 2000 Wydział Teologiczny Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu we współpracy z Fundacją Pomocy Humanitarnej „Redemptoris Missio” w Poznaniu postanowił kontynuować wydawanie czasopisma, któ- re zdobyło już określone miejsce w polskiej misjologii. Najpierw dwukrot- nie ukazało się pod tytułem przyjętym w roku 1932, z wyraźnym dodaniem określenia wskazującego na środowisko, z którym się utożsamia: „Annales Missiologicae Posnanienses” (t. 11-12). Jednak z uwagi na pewne wątpliwości dotyczące poprawności gramatycznej łacińskiego tytułu – po dłuższych waha- niach – po raz trzeci zmieniono tytuł: od tomu 13 (2003) przyjęto nazwę: „An- nales Missiologici Posnanienses”. W latach 2001-2014 pismo ukazywało się w rytmie dwurocznym. Od numeru 19 (2014) redakcja przyjęła roczny rytm wydawniczy. AANNALESNNALES MMISSIOLOGICIISSIOLOGICI PPOSNANIENSESOSNANIENSES Tom 21 2016 UNIWERSYTET IM. ADAMA MICKIEWICZA W POZNANIU • WYDZIAŁ TEOLOGICZNY ADAM MICKIEWICZ UNIVERSITY IN POZNAŃ • FACULTY OF THEOLOGY POZNAŃ, POLAND Rada Wydawnicza ks. prof. UAM dr hab. Adam Kalbarczyk, Mieczysława Makarowicz, ks. prof. UAM dr hab. Mieczysław Polak, ks. dr hab. Andrzej Pryba, ks. prof. UAM dr hab. Paweł Wygralak – przewodniczący Redaktor naczelny o. dr hab. Paweł Zając OMI e-mail: [email protected] Międzynarodowa Rada Naukowa o. prof. Marek Inglot SJ (Pontifi cia Università Gregoriana, Roma) o. prof. Artur K. Wardęga SJ (Macau Ricci Institute, Macau) prof. Frederic Laugrand (Universite Laval, Quebec) o. -

Parliament of Canada / Parlement Du Canada

PARLIAMENT OF CANADA / PARLEMENT DU CANADA The Dominion of Canada was created under the provisions of an Act of the Imperial Parliament (30 Victoria, Chapter III) passed in 1867, and formally cited as The British North America Act, 1867. This Act received Royal Assent, March 29th, 1867, and came into effect by virtue of Royal Proclamation, July 1st, 1867. The Constitution Act, 1867, provides: “There shall be one Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons.” (Clause 17) “There shall be a Session of the Parliament of Canada once at least in every year, so that twelve months shall not intervene between the last Sitting of the Parliament in one Session and its first Sitting in the next Session.” (Section 20) “Every House of Commons shall continue for five years from the Day of the Return of the Writs for choosing the House (subject to be sooner dissolved by the Governor General), and no longer.” (Section 50) “The Governor-General shall, from time to time, in the Queen's name, by instrument under the Great Seal of Canada, summon and call together the House of Commons.” (Section 38) “Either the English or the French language may be used by any person in the Debates of the House of the Parliament of Canada and of the House of the Legislation of Quebec, and both these languages are used in the respective records and Journals of those Houses; and either of those languages may be used by any person or in any Pleading or Process or in issuing from any Court of Canada established under the Constitution Act and in or from all or any of the Courts of Quebec.” (Section 133) “91. -

Rish Catholic Press in Toronto 1887 - 1892: the Years of Transition

1 CANADIAN JOURNAL OF COMMUNICATION, 1984, -10 (3), 27 - 46. THE !RISH CATHOLIC PRESS IN TORONTO 1887 - 1892: THE YEARS OF TRANSITION Gerald J. Stortz Wilf rid Laurier University The years 1850 - 1900 marked the apex for Irish Catholic journalism in Toron- to. During these years identification was on the basis of both ethnicity and religion. By century's end, however, the importance of ethnic identification waned and religion became the most important element. The rivalry between the last two Irish Catholic journals which ended with their replacement by a publication which was Catholic is indi- cative of this process. Les ann6es 1850 jusqu B 1900 repr6sen- taient 1 apog6e du journalisme Catholi- que irelandais. Pendant ces ann6es 1' ethnicit6 et la religion etaient les fondationa de l'identit6. Mais A la fin due si6cle la religion etait plus importante que 1'ethnicit&. La 1'emu- lation entre les deux derniers journaux Catholiques-irelandais cessait avec 1' 6tablissement d une publication seule- ment Catholique. The Irish Catholic press in Toronto flour- ished in the second half of the nineteenth cen- tury. There were a variety of reasons for this, not the least of which was the massive influx of immigrants during and immediately after the famine. Among these groups there was also a national pride which demanded an ethnic press. And the Irish press, like all journals benefited from the general rise in literacy and a strong interest in current events. By 1863, the market was strong enough to support two journals, the Irish Canadian and the Canadian Freeman. Each reflected a dominant train of thought within the Irish community.