Executive Compensation and Firm Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Smallcap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017

International SmallCap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017 SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS MARKET % OF SECURITY SHARES VALUE ASSETS AUSTRALIA INVESTA OFFICE FUND 2,473,742 $ 8,969,266 0.47% DOWNER EDI LTD 1,537,965 $ 7,812,219 0.41% ALUMINA LTD 4,980,762 $ 7,549,549 0.39% BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 677,708 $ 7,124,620 0.37% SEVEN GROUP HOLDINGS LTD 681,258 $ 6,506,423 0.34% NORTHERN STAR RESOURCES LTD 995,867 $ 3,520,779 0.18% DOWNER EDI LTD 119,088 $ 604,917 0.03% TABCORP HOLDINGS LTD 162,980 $ 543,462 0.03% CENTAMIN EGYPT LTD 240,680 $ 527,481 0.03% ORORA LTD 234,345 $ 516,380 0.03% ANSELL LTD 28,800 $ 504,978 0.03% ILUKA RESOURCES LTD 67,000 $ 482,693 0.03% NIB HOLDINGS LTD 99,941 $ 458,176 0.02% JB HI-FI LTD 21,914 $ 454,940 0.02% SPARK INFRASTRUCTURE GROUP 214,049 $ 427,642 0.02% SIMS METAL MANAGEMENT LTD 33,123 $ 410,590 0.02% DULUXGROUP LTD 77,229 $ 406,376 0.02% PRIMARY HEALTH CARE LTD 148,843 $ 402,474 0.02% METCASH LTD 191,136 $ 399,917 0.02% IOOF HOLDINGS LTD 48,732 $ 390,666 0.02% OZ MINERALS LTD 57,242 $ 381,763 0.02% WORLEYPARSON LTD 39,819 $ 375,028 0.02% LINK ADMINISTRATION HOLDINGS 60,870 $ 374,480 0.02% CARSALES.COM AU LTD 37,481 $ 369,611 0.02% ADELAIDE BRIGHTON LTD 80,460 $ 361,322 0.02% IRESS LIMITED 33,454 $ 344,683 0.02% QUBE HOLDINGS LTD 152,619 $ 323,777 0.02% GRAINCORP LTD 45,577 $ 317,565 0.02% Not FDIC or NCUA Insured PQ 1041 May Lose Value, Not a Deposit, No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee 07-17 Not Insured by any Federal Government Agency Informational data only. -

2014 , דצמבר 10 231791 4201 דצמבר – עדכון הרכבי מדדי המניות : הנדון . 2014

10 דצמבר, 2014 231791 הנדון: עדכון הרכבי מדדי המניות – דצמבר 2014 הננו להודיעכם כי הרכבי מדדי המניות יעודכנו ביום 15 בדצמבר 2014. 1. לא יחול שינוי בהרכבי המדדים הבאים (7 מדדים): ת"א-בנקים, ת"א-פיננסים, ת"א-ביטוח, ת"א טק-עילית, ת"א-נפט וגז, ת"א-מעלה ותל-דיב. 2. מצ"ב הרכבי המדדים אשר יחולו בהם שינויים. 3. הרכבי המדדים פורסמו גם בגיליונות אקסל בדף הודעות מדדים חדש באתר הבורסה. על מנת לראות את הרכבי המדדים באתר הבורסה יש להקליק על "מוצרים" בחלונית הקישורים הכחולה מימין > מדדים > הודעות מדדים > קטגוריה: "הודעות עדכון מדדים". בברכה (-) עמית רחמני מדדי הבורסה -17- ת"א-מאגר סד' מספר נייר שם נייר בעברית שם נייר באנגלית ISIN 1 103010 טיב טעם IL0001030100 TIV TAAM 2 126011 גזית גלוב IL0001260111 GAZIT GLOBE 3 127019 מבטח שמיר IL0001270193 MIVTACH SHAMIR 4 146019 אלרוב ישראל IL0001460190 ALROV 5 155036 מנרב IL0001550362 MINRAV 6 161018 וואן טכנולוגיות IL0001610182 ONE TECHNOLOGI 7 168013 נטו אחזקות IL0001680136 NETO 8 198010 כלכלית ירושלים IL0001980106 JERUSALEM ECON 9 208017 נאוי IL0002080179 NAWI 10 216010 וויטסמוק IL0002160104 WHITESMOKE 11 224014 כלל עסקי ביטוח IL0002240146 CLAL INSURANCE 12 226019 מבני תעשיה IL0002260193 INDUS BUILDING 13 230011 בזק IL0002300114 BEZEQ 14 232017 ישראמקו יהש IL0002320179 ISRAMCO L 15 243014 חנל יהש IL0002430143 HLDS L 16 251017 אשטרום נכסים IL0002510175 ASHTROM PROP 17 253013 מדטכניקה IL0002530132 MEDTECHNICA 18 256016 פורמולה מערכות IL0002560162 FORMULA 19 260018 אורמת IL0002600182 ORMAT 20 265017 אורביט IL0002650179 ORBIT 21 268011 אבנר יהש IL0002680119 AVNER L 22 273011 נייס IL0002730112 NICE 23 274019 נפטא -

Coronavirus and Its Impact on Israeli Public Companies in Recent Weeks

Coronavirus and Its Impact on Israeli Public Companies In recent weeks we have seen global capital markets colored red, following the corona virus outbreak worldwide, which many experts have been calling an “international epidemic”. The reaction of investors to the spread of corona virus has been characterized largely by panic in countries around the world and this has led to a sharp declines not seen since the global financial crisis in 2008 . The State of Israel has taken extensive, some have said extreme, steps, to limit the spread of the virus, one being a directive to self-isolate for 14 days for returnees from every destination in the world. As a result, airlines and tourism businesses in Israel have begun the process of layoffs and putting other workers on unpaid leave. In recent days the Israel Securities Authority has issued new guidelines for reporting companies in Israel, decreeing that in light of the spread of the virus, reporting entities exposed directly or indirectly must provide to the investing public detailed information, among other things, about the material consequences and effects of the corona virus on the results of their business activities in the near future as well as on how they will deal with the risks and exposures. Many reporting entities, including El Al, OPC Energy, IBI Investment House, Kishrei Teufa and Arad have issued announcements to the investing public about the real possibility of a negative impact on their business operations. In the field of tourism, Israel’s national airline, El Al, recently announced that in light of the new guidelines of the Ministry of Health, it is unable at this stage to assess the extent of the adverse effect on the company’s operations. -

Symbol Name SFET.TA Safe-T Group Ltd NNDM.TA Nano Dimension Ltd

Symbol Name SFET.TA Safe-T Group Ltd NNDM.TA Nano Dimension Ltd ORL.TA Bazan Oil Refineries Ltd MDGS.TA Medigus Ltd DSCT.TA Israel Discount Bank Ltd ISRAp.TA Isramco Negev 2 LP LUMI.TA Leumi BEZQ.TA Bezeq Israeli Telecommunication Corp Ltd POLI.TA Poalim ELAL.TA El Al MGDL.TA Migdal Insurance RATIp.TA Ratio L FRSX.TA Foresight Autonomous Holdings Ltd CANF.TA Can Fite Biopharma Ltd DEDRp.TA Delek Drilling LP ARKO.TA Arko Holdings Ltd GIVOp.TA Givot L ICL.TA ICL Israel Chemicals Ltd ENLT.TA Enlight Ene CNMD.TA Proteologics Ltd MLD.TA Mirland Development Corporation PLC SLARL.TA Sella Real Estate SKBN.TA Shikun & Binui TEVA.TA Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd XTL.TA XTL Bio MVNE.TA Mivne Real Estate KD Ltd ISCD.TA Isracard Ltd KDST.TA Kadimastem Ltd ADKA.TA Adika Style ICCM.TA Icecure Medical TMRP.TA Tamar Petroleum Ltd BONS.TA Bonus Biogroup AURA.TA Aura Investments Ltd GZT.TA Gazit Globe Ltd GNRS.TA Generation Capital Ltd ADGR.TA Adgar Investments and Development Ltd GOLF.TA Golf ARPT.TA Airport City Ltd APLY.TA Apply Advanced Mobile Technologies Ltd NXGN.TA Nextgen ALHE.TA Alony Hetz Properties and Investments Ltd ENRG.TA Energix RANI.TA Rani Zim Shopping Centers ARNA.TA Arena Star Group Ltd RTPTp.TA Ratio Petroleum Energy LP MZTF.TA Mizrahi Tefahot BVC.TA Batm Advanced Communications Ltd BLRX.TA BioLine RX Ltd AMOT.TA Amot Investments Ltd INCR.TA Intercure MNRT.TA Menivim The New REIT Ltd ASPF.TA Altshuler Shaham Funds Pension Ltd SAE.TA Shufersal RIT1.TA Reit 1 SPEN.TA Shapir Engineering Industry KMDA.TA Kamada INBR.TA Inbar Group -

The Israel Business Conference 2007 - Program

The Israel Business Conference 2007 - Program Sunday 9 December 9:00 - 11:00 Opening plenum: Where is the world going, and is Israel going too? What changed this year? A close look at global growth engines and trends and where the smart money is going. How should Israeli enterprise gear up to face the future? Introduction: Haggai Golan, Editor-in-Chief, Globes Session chair: Robert Friedman, International Editor, Fortune Keynote speakers: Abby Joseph Cohen, Partner and Chief US Investment Strategist, Goldman Sachs; Prof. Jacob Frenkel, Vice Chairman, AIG; Chairman, G-30; Former Governor, Bank of Israel; Deven Sharma, President, Standard & Poor's 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee break 11:30 - 13:00 Simultaneous sessions Roundtable* What's worrying the banks? Cellular communications' brave new Disciplines of leadership International sporting events as business How will competition affect the players? world Concepts of the leader in business, sport, opportunities How to handle credit risk? What business models will dominate and communications. Case Study: 2012 UEFA European Championship How will the Supervision Law affect fees? cellular internet? Which will win – Are leaders judged by their vision or their in Ukraine Should Israeli banks be opening branches WiMAX or 3.5G LTE? What will the management skills? Session chair: Boaz Hirsch, Director of Foreign overseas? new handsets look like? Will vendors Session chair: Ilan Cohen, Former Trade, Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labor Session chair: Dr. Yossi Bachar, CEO, switch to applications? Director -

Bank Leumi Le-Israel B.M. Immediate Report on Convening of General

Page 1 of 94 046T PUBLIC Bank Leumi le-Israel B.M. Registration No. 520018078 Securities of the Corporation are listed on The Tel Aviv Stock Exchange Abbreviated Name: Leumi Leumi House, 34 Yehuda Halevi Street, Tel Aviv 65546 Phone: + 972 3 5148111, + 972 3 5149419; Facsimile: + 972 3 514-9732 Electronic Mail: [email protected] Date Sent: April 13, 2011 Reference: 2011-01-120114 To: To: The Israel Securities Authority The Tel-Aviv Stock Exchange, Ltd. www.isa.gov.il www.tsae.co.il Amending Report to the Report sent on April 11, 2011, reference no. 2011-01-116610. Error: Amendment of details of candidates for Directors Reason for error: Amendment of details of candidates for Directors Main amendment: Amendment of details of candidates for Directors Immediate Report on Convening of General Meeting Regulation 36B (a) and 36C of the Securities (Periodic and Immediate Reports) Regulations, 1970 Explanation: If one of the topics on the agenda of the meeting is the approval of a transaction with a controlling shareholder or approval of an irregular offering, fill out form 133T or 138T accordingly. One of the topics on the agenda of the meeting is approval of a transaction with a controlling shareholder or one that the controlling shareholder has a personal interest in or approval of a private irregular or significant offering. 1. On April 11, 2011 it was decided to convene an Annual General Meeting which will convene on Tuesday, May 24, 2011 at 10:30 at Lin House, 35 Yehuda Halevi Street, Tel- Aviv. The securities number that allows its holder to participate in the meeting is 604611. -

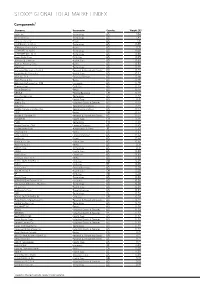

Stoxx® Global Total Market Index

STOXX® GLOBAL TOTAL MARKET INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Apple Inc. Technology US 1.84 Microsoft Corp. Technology US 1.47 Amazon.com Inc. Retail US 1.31 FACEBOOK CLASS A Technology US 0.89 JPMorgan Chase & Co. Banks US 0.71 ALPHABET CLASS C Technology US 0.68 ALPHABET INC. CL A Technology US 0.66 Exxon Mobil Corp. Oil & Gas US 0.65 Johnson & Johnson Health Care US 0.63 Bank of America Corp. Banks US 0.53 Intel Corp. Technology US 0.49 Samsung Electronics Co Ltd Personal & Household Goods KR 0.49 UnitedHealth Group Inc. Health Care US 0.47 VISA Inc. Cl A Financial Services US 0.46 Wells Fargo & Co. Banks US 0.46 Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Cl B Insurance US 0.46 Chevron Corp. Oil & Gas US 0.45 Home Depot Inc. Retail US 0.44 NESTLE Food & Beverage CH 0.44 Cisco Systems Inc. Technology US 0.42 Pfizer Inc. Health Care US 0.41 Boeing Co. Industrial Goods & Services US 0.40 AT&T Inc. Telecommunications US 0.39 Verizon Communications Inc. Telecommunications US 0.37 HSBC Banks GB 0.37 Procter & Gamble Co. Personal & Household Goods US 0.37 NOVARTIS Health Care CH 0.36 TSMC Technology TW 0.35 MasterCard Inc. Cl A Financial Services US 0.35 Toyota Motor Corp. Automobiles & Parts JP 0.35 Citigroup Inc. Banks US 0.33 Coca-Cola Co. Food & Beverage US 0.32 Netflix Inc. Retail US 0.32 Merck & Co. Inc. Health Care US 0.32 Walt Disney Co. Media US 0.31 NVIDIA Corp. -

El Al Israel Airlines

Translation of the Hebrew Language financial statements EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. 2006 ANNUAL REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD CHAPTER A - OVERVIEW OF THE ENTITY'S BUSINESS CHAPTER B - DIRECTORS' REPORT CHAPTER C - 2006 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Greetings, El Al's financial results for 2006 emphasize above all the Company's strength and its ability to overcome obstacles, business wise and market wise, even when all external negative variables join forces and create a negative trend. 2006 has presented El Al with numerous challenges which, each on its own, and without doubt all of them combined together, have an intense effect on the Company's operations. Fuel price increased to new historic records during 2006, adding approximately 136.9 million US dollars, excluding hedging activities, to the company's expenses. Hedging activities performed according to Company's hedging policy saved approximately 52.3 million US dollars in fuel costs during 2006. Unprecedented increase in competition and in the overall capacity, was reflected by an increase of 21% in seat supply offered by schedule Airlines (namely, an increase of seat supply by 840 thousand seats), in light of approximately 6% increase in traffic at Ben-Gurion Airport. Regulatory changes led to unprecedented utilization of the "Sixth Freedom" by foreign carriers, which is basically translated to an increase in number of passengers traveling out of Israel via the foreign carrier's hub to any third destination around the world. Weakening of the US currency in relation to other currencies caused an increase in the company's expenses. -

STOXX Developed Markets 2400 Last Updated: 01.05.2018

STOXX Developed Markets 2400 Last Updated: 01.05.2018 Rank Rank (PREVIOUS ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) ) US0378331005 2046251 AAPL.OQ AAPL Apple Inc. US USD Y 702.3 1 1 US5949181045 2588173 MSFT.OQ MSFT Microsoft Corp. US USD Y 597.1 2 2 US0231351067 2000019 AMZN.OQ AMZN Amazon.com Inc. US USD Y 522.4 3 3 US30303M1027 B7TL820 FB.OQ US20PD FACEBOOK CLASS A US USD Y 341.1 4 4 US46625H1005 2190385 JPM.N CHL JPMorgan Chase & Co. US USD Y 312.4 5 5 US4781601046 2475833 JNJ.N JNJ Johnson & Johnson US USD Y 281.3 6 6 US30231G1022 2326618 XOM.N XON Exxon Mobil Corp. US USD Y 272.7 7 8 US02079K1079 BYY88Y7 GOOG.OQ US40C2 ALPHABET CLASS C US USD Y 261.1 8 7 US0605051046 2295677 BAC.N NB Bank of America Corp. US USD Y 237.4 9 9 US0846707026 2073390 BRKb.N BRKB Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Cl B US USD Y 203.4 10 10 CH0038863350 7123870 NESN.S 461669 NESTLE CH CHF Y 200.3 11 11 US4581401001 2463247 INTC.OQ INTC Intel Corp. US USD Y 200.0 12 12 US1667641005 2838555 CVX.N CHV Chevron Corp. US USD Y 196.7 13 16 US9497461015 2649100 WFC.N NOB Wells Fargo & Co. US USD Y 190.9 14 13 US92826C8394 B2PZN04 V.N U0401 VISA Inc. Cl A US USD Y 190.2 15 15 US91324P1021 2917766 UNH.N UNH UnitedHealth Group Inc. US USD Y 189.2 16 20 US17275R1023 2198163 CSCO.OQ CSCO Cisco Systems Inc. -

El Al Israel Airlines

Free Translation of the Hebrew Language 2007 Annual Report - Hebrew Wording Binding EL AL ISRAEL AIRLINES LTD. 2007 ANNUAL REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD CHAPTER A - OVERVIEW OF THE ENTITY'S BUSINESS CHAPTER B - DIRECTORS' REPORT CHAPTER C - 2007 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Greetings, The financial results of El Al for the year 2007, showing the highest level of revenues since the Company was established, are proof above all of El Al’s financial strength and its ability to deal with an ever intensifying competitive reality. In 2007, El Al achieved the targets it had set itself, including increasing revenues, reducing costs, and ensuring correct management of the Company’s inputs, all with the overall aim of continuing to operate as a profitable and financially robust company, one that puts its emphasis on attentive, high quality service for the benefit of its customers, staff and shareholders, while continuing with its investment plan. The Company continues to work towards greater efficiency, by cutting back on inefficient and unprofitable routes, expanding its activities in the Far East, and increasing flight frequencies to popular destinations, such as New York and Los Angeles. In 2007, the Company recorded a record income of 1.9 billion dollars, representing an increase of about 16% compared with the same period in the previous year. During 2007, El Al put the emphasis on efficient utilization of its fleet of aircraft, as shown by the very high load factor in the company aircrafts - 85%. All this was achieved in spite of growing competition, which is characterized by an increase in the number of seats offered by foreign companies and by competition in the freight business. -

Outlook for M&A in Israel

Innovation drives In this publication, White & Case means the international legal practice comprising dealmaking: OutlookWhite & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law for M&A in Israel and all other affi liated partnerships, companies and entities. This publication is prepared for Competition for technological expertise has the general information of our transformed Israel’s M&A landscape as clients and other interested persons. It is not, and does not dealmakers strive to stay ahead of the curve attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice. ATTORNEY ADVERTISING. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. 2 White & Case W&C_Israel_MA2017_v15_AP.indd 1 15/06/2017 18:30:59 Contents Israel M&A scales new heights Page 1 Disruption fuels deals Page 3 Tech leads the way Page 6 A positive outlook Page 8 Regulation: Where challenge meets opportunity Page 10 Conclusion: Looking ahead Page 12 II White & Case W&C_Israel_MA2017_v15_AP.indd 2 15/06/2017 18:31:02 Israel M&A scales new heights Investors continue to flock to Israel, as innovation and technological advancements create fertile ground for M&A. The country’s leading expertise in cybersecurity is proving a key draw for dealmakers David Becker ubbed the “startup nation,” Israel is an epicenter of innovation. It boasts more venture Partner, White & Case capital firms and startups on a per capita basis than any other country in the world. In tech terms, it is second only to Silicon Valley. -

Stoxx® Developed Markets Total Market Index

STOXX® DEVELOPED MARKETS TOTAL MARKET INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Microsoft Corp. Technology US 3.07 Apple Inc. Technology US 3.00 Amazon.com Inc. Retail US 2.34 FACEBOOK CLASS A Technology US 1.19 ALPHABET CLASS C Technology US 0.89 ALPHABET INC. CL A Technology US 0.88 Johnson & Johnson Health Care US 0.79 NESTLE Food & Beverage CH 0.70 VISA Inc. Cl A Financial Services US 0.68 JPMorgan Chase & Co. Banks US 0.64 Procter & Gamble Co. Personal & Household Goods US 0.61 UnitedHealth Group Inc. Health Care US 0.57 Home Depot Inc. Retail US 0.56 MasterCard Inc. Cl A Financial Services US 0.54 Intel Corp. Technology US 0.53 ROCHE HLDG P Health Care CH 0.52 Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Cl B Insurance US 0.52 Verizon Communications Inc. Telecommunications US 0.48 NVIDIA Corp. Technology US 0.47 NOVARTIS Health Care CH 0.45 AT&T Inc. Telecommunications US 0.45 ADOBE Technology US 0.43 Walt Disney Co. Media US 0.43 Netflix Inc. Media US 0.41 Merck & Co. Inc. Health Care US 0.41 Bank of America Corp. Banks US 0.41 Exxon Mobil Corp. Oil & Gas US 0.40 PayPal Holdings Industrial Goods & Services US 0.40 Cisco Systems Inc. Technology US 0.40 Pfizer Inc. Health Care US 0.38 PepsiCo Inc. Food & Beverage US 0.38 Coca-Cola Co. Food & Beverage US 0.37 Comcast Corp. Cl A Media US 0.37 ABBVIE Health Care US 0.35 Chevron Corp. Oil & Gas US 0.35 Salesforce.com Inc.