SUB POP Shaping the Direction of That Scene Was Bruce Pavitt, Sub Pop’S Founder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Let's Say You're in a Band

Hello from Jenny Toomey & Kristin John Henderson’s CD tidbits were right on the money. In the fourth edition we Thomson and welcome to the 2000 added a bit of basic info on publishing, copyrighting, “going legal”. For this one digital version of the Mechanic’s we’ve updated some of the general info and included some URLs for some of Guide. Between 1990 and 1998 the companies that can help with CD or record production. we ran an indie record label called Simple Machines. Over One thing to keep in mind. This booklet is just a basic blueprint, and even though those eight years we we write about putting out records or CDs, a lot of this is common sense. We released about 75 records by know people who have used this kind of information to do everything from our own bands and those of putting out a 7” to starting an independent clothing label to opening recording our friends. We closed the studios, record stores, cafes, microbreweries, thrift stores, bookshops, and now whole operation down in thousands of start-up internet companies. Some friends have even used similar March, 1997. skills to organize political campaigns and rehabilitative vocational programs offering services to youth offenders in DC. Ironically, one of our label's most popular releases was There is nothing that you can’t do with a little time, creativity, enthusiasm and not a record, but a 24-page hard work. An independent business that is run with ingenuity, love and a sense "Introductory Mechanics of community can even be more important than the products and services it Guide to Putting out sells because an innovative business will, if successful, stretch established defini- Records”. -

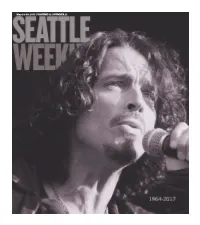

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

Living and Labouring As a Music Writer

Cultural Studies Review volume 19 number 1 March 2013 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 155–76 Lawson Fletcher and Ramon Lobato 2013 Living and Labouring as a Music Writer LAWSON FLETCHER AND RAMON LOBATO SWINBURNE UNIVERSITY I attended gigs most weeks while studying at university. I was happy to remain a punter until around May, June 2007. A band called Cog played at The Tivoli. After the show, I read a review on FasterLouder.com.au which was poorly-written and factually incorrect—they mentioned a few songs that weren’t played. It pissed me off. I thought: ‘I can do better.’ So I wrote a review of a show I saw that same weekend—Karnivool at The Zoo—and sent it to the Queensland editor of FasterLouder.com.au … He liked it, and published it. I sent the same review to the editor of local street press Rave Magazine, who also liked it, and decided to take me on as an ‘indie’ CD reviewer; later, I started writing live reviews for Rave, too. ‘Dale’, a 23-year old freelance music writer Like most music critics in Australia, Dale is an autodidact. His entry into a writing career started with ad hoc reviews for websites and local music magazines. Over ISSN 1837-8692 time he built up a network of contacts, carefully honed his craft, and is now making a living by writing reviews and interviews for various magazines and websites. The money isn’t good, but it’s enough to live off—and Dale relishes the opportunity to influence how his readers understand and enjoy the culture around them and contribute to a wider conversation about music. -

Rill^ 1980S DC

rill^ 1980S DC rii£!St MTEVOLUTIO N AND EVKllMSTINO KFFK Ai\ liXTEiniKM^ WITH GUY PICCIOTTO BY KATni: XESMITII, IiV¥y^l\^ IKWKK IXSTRUCTOU: MR. HiUfiHT FmAL DUE DATE: FEBRUilRY 10, SOOO BANNED IN DC PHOTOS m AHEcoorts FROM THE re POHK UMOEAG ROUND pg-ssi OH t^€^.S^ 2006 EPISCOPAL SCHOOL American Century Oral History Project Interviewee Release Form I, ^-/ i^ji^ I O'nc , hereby give and grant to St. Andrew's (interviewee) Episcopal School llie absolute and unqualified right to the use ofmy oral history memoir conducted by KAi'lL I'i- M\-'I I on / // / 'Y- .1 understand that (student interviewer) (date) the purpose of (his project is to collect audio- and video-taped oral histories of first-hand memories ofa particular period or event in history as part of a classroom project (The American Century Project). 1 understand that these interviews (tapes and transcripts) will be deposited in the Saint Andrew's Episcopal School library and archives for the use by ftiture students, educators and researchers. Responsibility for the creation of derivative works will be at the discretion of the librarian, archivist and/or project coordinator. I also understand that the tapes and transcripts may be used in public presentations including, but not limited to, books, audio or video doe\imcntaries, slide-tape presentations, exhibits, articles, public performance, or presentation on the World Wide Web at t!ic project's web site www.americaiicenturyproject.org or successor technologies. In making this contract I understand that I am sharing with St. Andrew's Episcopal School librai-y and archives all legal title and literary property rights which i have or may be deemed to have in my inten'iew as well as my right, title and interest in any copyright related to this oral history interview which may be secured under the laws now or later in force and effect in the United States of America. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

![D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4019/d841o-free-download-love-death-the-murder-of-kurt-cobain-online-144019.webp)

D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online

d841o [Free download] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Online [d841o.ebook] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Pdf Free Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #289088 dans eBooksPublié le: 2014-03-20Sorti le: 2014-03- 20Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 26.Mb Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin : Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. A couper le soufflePar TichatDu vrai journalisme investigatif. Bien écrit, très bien recherché, objectif, avec des révélations inattendues et hallucinantes.Se lit tel qu'un thriller à en oublier presque qu'il s'agit malheureusement de faits réels.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?Par guichardGREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ? Présentation de l'éditeurTHE EXPLOSIVE INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN. Friday, 8th April 1994. Kurt Cobain's body was discovered in a room above a garage in Seattle. For the attending authorities, it was an open-and-shut case of suicide. What no one knew was Cobain had been murdered. That April, Cobain went missing for several days, or so it seemed: in fact, some people knew where he was, and one of them was Courtney Love. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

Dag Nasty Wig out at Denkos Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dag Nasty Wig Out At Denkos mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Wig Out At Denkos Country: US Released: 1987 Style: Hardcore, Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1868 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1240 mb WMA version RAR size: 1751 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 350 Other Formats: AC3 MP3 MP4 MPC DMF AIFF AUD Tracklist A1 The Godfather A2 Trying A3 Safe A4 Fall A5 When I Move B1 Simple Minds B2 Wig Out At Denkos B3 Exercise B4 Dag Nasty B5 Crucial Three Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Dischord Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dischord Records Produced At – Inner Ear Studios Recorded At – Inner Ear Studios Pressed By – MPO Credits Bass – Doug Carrion Drums – Colin Sears Engineer – Don Zientara Graphics – Cynthia Connolly Guitar – Brian Baker Photography By – Ken Salerno, Tomas Squip Producer – Don*, Ian* Songwriter – Dag Nasty Vocals – Peter Cortner Notes Includes black and white insert with lyrics one the one and a photo on the other side Produced at Inner Ear Studios. Recorded at Inner Ear Studios. This album is $5. postpaid from Dischord Records. c & p 1987 Dischord Records. Made in France. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout A [etched]): DISCHORD 26 A-1 MPO Matrix / Runout (Runout B [etched]): DISCHORD 26 B-1 MPO Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Dag Wig Out At Denkos Dischord Dischord 26 Dischord 26 US 1987 Nasty (LP, Album) Records Wig Out At Denko's Dag Dischord DIS26CD (CD, Album, RE, DIS26CD US 2002 Nasty Records RM) Dischord Dischord 26, Dischord 26, Dag Wig Out At Denkos Records, Dischord Dischord US Unknown Nasty (LP, Album, RP) Dischord Records 26 Records 26 Records Dag Wig Out At Denkos Dischord Dischord 26 Dischord 26 UK 1987 Nasty (LP, Album, TP) Records Dischord Records, Wig Out At Denkos 26, dis26v, Dag Dischord 26, dis26v, (LP, Album, RM, US 2009 Dischord 26 Nasty Records, Dischord 26 RP) Dischord Records Related Music albums to Wig Out At Denkos by Dag Nasty 1. -

201611 Indie 001.Pdf

NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA Bleach Bleach Bleach Bleach Nevermind ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1989年 SUB POP 【SP34】 1989年 WATERFRONT 【DAMP114】 1989年 WATERFRONT 【DAMP114】 1996年 UNIVERSAL 【MVJG25002】 1991年 DGC 【DGC24425】 US ORIGNAL LP AUSTRALIA ORIGINAL LP AUSTRALIA ORIGINAL LP 日本盤 LP US ORIGNAL LP POSTER 帯付 / ライナーノーツ INNER SLEEVE WHITE VINYL / SP-34-A Kdisc ch L.32926 BLACK/SLIVER SLEEVE PURPLE VINYL / PURPLE SLEEVE REMASTER MASTERDISK刻印 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥100,000 価格 ¥50,000 価格 ¥40,000 価格 ¥5,000 価格 ¥15,000 NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA Nevermind Nevermind Nevermind In Utero In Utero ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1996年 UNIVERSAL 【MVJG25001】 1996年 MOBILE FIDELITY SOUND LAB 【MFSL1-258】 2007年 UNIVERSAL 【UIJY9009】 1993年 DGC 【DGC24607】 1996年 UNIVERSAL 【MVJG25004】 日本盤初版 LP US盤 LP 日本盤 LP US ORIGNAL LP 日本盤 LP 帯付 / INNER SLEEVE / ライナーノーツ 帯付 INNER SLEEVE 帯付 / INNER SLEEVE / ライナーノーツ REMASTER GATE FOLD SLEEVE / 200g / NUMBERD / 高音質盤 200g / 名盤LP100選 CLEAR VINYL REMASTER 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥7,000 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥3,000 価格 ¥10,000 価格 ¥5,000 NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA NIRVANA Incesticide Incesticide MTV Unplugged In New York MTV Unplugged In New York From The Muddy Banks Of The Wishkah ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 ◆画像 1992年 DGC 【DGC24504】 1996年 UNIVERSAL 【MVJG25003】 1994年 DGC 【DGC24727】 1996年 UNIVERSAL 【MVJG25005】 1996年 DGC 【DGC25105】 US ORIGNAL LP 日本盤 LP US ORIGNAL LP 日本盤 LP US ORIGNAL 2LP INNER SLEEVE 帯付 / INNER SLEEVE / ライナーノーツ INNER SLEEVE 帯付 / INNER SLEEVE / ライナーノーツ INNER SLEEVE BLUE VINYL REMASTER WHITE VINYL 買取 買取 買取 買取 買取 価格 ¥8,000 価格 ¥4,000 価格 ¥5,000 -

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brett Morgen | 160 pages | 05 May 2015 | Insight Editions, Div of Palace Publishing Group, LP | 9781608875498 | English | San Rafael, United States Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck PDF Book You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck makes a persuasive case for its subject without resorting to hagiography -- and includes plenty of rare and unreleased footage for fans. Sign In. Rolling Stone. After Kurt Cobain is born in , his parents move to Aberdeen, Washington and shortly after his sister Kim is born. Kurt Cobain. Archived from the original on November 19, Book Category. After recording their next album, Nevermind , their song " Smells Like Teen Spirit " becomes a hit and the band is launched into the mainstream. Kurt Cobain: Montage Of Heck After a short while, Kurt breaks up with Tracy. Bleach Nevermind In Utero. Helen Razer. Nevertheless, Kyle Anderson of Entertainment Weekly praised the album, considering it as "a cultural artifact that provides an inside look at the creative process of an enigmatic genius. Cobain's mother, Wendy, had regret in relation to working on the film. Archived from the original on February 6, We would have known that story. Downloads Wrong links Broken links Missing download Add new mirror links. We get a very intimate glimpse of the beloved musician from his early years all the way up to , when he tragically took his own life at the age of After he attempts to have sex with the girl, his classmates begin insulting and shaming him. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST.