Encinas, Enrique (2018) the Offject. a Design Theory of Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World's Religions After September 11

The World’s Religions after September 11 This page intentionally left blank The World’s Religions after September 11 Volume 1 Religion, War, and Peace EDITED BY ARVIND SHARMA PRAEGER PERSPECTIVES Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The world’s religions after September 11 / edited by Arvind Sharma. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-275-99621-5 (set : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3 : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4 : alk. paper) 1. Religions. 2. War—Religious aspects. 3. Human rights—Religious aspects. 4. Religions—Rela- tions. 5. Spirituality. I. Sharma, Arvind. BL87.W66 2009 200—dc22 2008018572 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2009 by Arvind Sharma All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008018572 ISBN: 978-0-275-99621-5 (set) 978-0-275-99623-9 (vol. 1) 978-0-275-99625-3 (vol. 2) 978-0-275-99627-7 (vol. 3) 978-0-275-99629-1 (vol. 4) First published in 2009 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). -

Full Complaint

Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 1 of 602 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ESTATE OF ROBERT P. HARTWICK, § HALEY RUSSELL, HANNAH § HARTWICK, LINDA K. HARTWICK, § ROBERT A. HARTWICK, SHARON § SCHINETHA STALLWORTH, § ANDREW JOHN LENZ, ARAGORN § THOR WOLD, CATHERINE S. WOLD, § CORY ROBERT HOWARD, DALE M. § HINKLEY, MARK HOWARD BEYERS, § DENISE BEYERS, EARL ANTHONY § MCCRACKEN, JASON THOMAS § WOODLIFF, JIMMY OWEKA OCHAN, § JOHN WILLIAM FUHRMAN, JOSHUA § CRUTCHER, LARRY CRUTCHER, § JOSHUA MITCHELL ROUNTREE, § LEIGH ROUNTREE, KADE L. § PLAINTIFFS’ HINKHOUSE, RICHARD HINKHOUSE, § SECOND AMENDED SUSAN HINKHOUSE, BRANDON § COMPLAINT HINKHOUSE, CHAD HINKHOUSE, § LISA HILL BAZAN, LATHAN HILL, § LAURENCE HILL, CATHLEEN HOLY, § Case No.: 1:18-cv-01612-CKK EDWARD PULIDO, KAREN PULIDO, § K.P., A MINOR CHILD, MANUEL § Hon. Colleen Kollar-Kotelly PULIDO, ANGELITA PULIDO § RIVERA, MANUEL “MANNIE” § PULIDO, YADIRA HOLMES, § MATTHEW WALKER GOWIN, § AMANDA LYNN GOWIN, SHAUN D. § GARRY, S.D., A MINOR CHILD, SUSAN § GARRY, ROBERT GARRY, PATRICK § GARRY, MEGHAN GARRY, BRIDGET § GARRY, GILBERT MATTHEW § BOYNTON, SOFIA T. BOYNTON, § BRIAN MICHAEL YORK, JESSE D. § CORTRIGHT, JOSEPH CORTRIGHT, § DIANA HOTALING, HANNA § CORTRIGHT, MICHAELA § CORTRIGHT, LEONDRAE DEMORRIS § RICE, ESTATE OF NICHOLAS § WILLIAM BAART BLOEM, ALCIDES § ALEXANDER BLOEM, DEBRA LEIGH § BLOEM, ALCIDES NICHOLAS § BLOEM, JR., VICTORIA LETHA § Case 1:18-cv-01612-CKK Document 11 Filed 11/17/18 Page 2 of 602 BLOEM, FLORENCE ELIZABETH § BLOEM, CATHERINE GRACE § BLOEM, SARA ANTONIA BLOEM, § RACHEL GABRIELA BLOEM, S.R.B., A § MINOR CHILD, CHRISTINA JEWEL § CHARLSON, JULIANA JOY SMITH, § RANDALL JOSEPH BENNETT, II, § STACEY DARRELL RICE, BRENT § JASON WALKER, LELAND WALKER, § SUSAN WALKER, BENJAMIN § WALKER, KYLE WALKER, GARY § WHITE, VANESSA WHITE, ROYETTA § WHITE, A.W., A MINOR CHILD, § CHRISTOPHER F. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Mutual Influence of Science Fiction and Innovation

Nesta Working Paper No. 13/07 Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation Caroline Bassett Ed Steinmueller George Voss Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation Caroline Bassett Ed Steinmueller George Voss Reader in Digital Media, Professor of Information and Research Fellow, Faculty of Arts, Research Centre for Material Technology, SPRU, University University of Brighton, Visiting Digital Culture, School of of Communication Sussex Fellow at SPRU, University of Media, Film and Music, Sussex University of Sussex Nesta Working Paper 13/07 March 2013 www.nesta.org.uk/wp13-07 Abstract This report examines the relationship between SF and innovation, defined as one of mutual engagement and even co-constitution. It develops a framework for tracing the relationships between real world science and technology and innovation and science fiction/speculative fiction involving processes of transformation, central to which are questions of influence, persuasion, and desire. This is contrasted with the more commonplace assumption of direct linear transmission, SF providing the inventive seed for innovation– instances of which are the exception rather than the rule. The model of influence is developed through an investigation of the nature and evolution of genre, the various effects/appeals of different forms of expression, and the ways in which SF may be appropriated by its various audiences. This is undertaken (i) via an inter- disciplinary survey of work on SF, and a consideration the historical construction of genre and its on-going importance, (ii) through the development of a prototype database exploring transformational paths, and via more elaborated loops extracted from the database, and (iii) via experiments with the development of a web crawl tool, to understand at a different scale, using tools of digital humanities, how fictional ideas travel. -

North American Indians

INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA • land boys and foreign tourists) along more AmericanIndianreligions emphasizedthe Mediterranean or pederastic lines will freedom of individuals to follow theirown develop. inclinations, as evidence of guidance from Apart from caste and family obli theirpersonalspiritguardian, and to share gations, however, Indian society is re generously what they had with others. markablytolerant of individualeccentrici Children's sexual play was more ties, and it is quite possible that when the likely to be regarded by adults as an amus curtainfinally liftsonIndian sexualityone ing activity rather than as a cause for may find the patterns ofhomosexualityin alarm. This casual attitude of child-rear India distinctively Indian. ingcontinued to influence people as they grew up, and even after their marriage. BIBLIOGRAPHY. Ejaz Ahmad, ulw Yet, while sex was certainly much more Relating to Sexual Offenses, 2nd ed., Allahabad: Ashoka Law House, 1975; J. accepted than in the Judeo-Christian tra P. Bhatnagar, Sexual Offenses, Al dition, it was not the major emphasis of lahabad: Ashoka Law House, 1987; Indian society. The focus was instead on Shakuntala Devi, The World ofHomo two forms of social relations: family sexuals, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing (making ties to other genders) and friend House, 1977; Serena Nanda, "The Hijras of India: Cultural and Individual ship (making ties within the samegender). Dimensions of an Institutionalized Third Since extremely close friendships were Gender Role," in Evelyn Blackwood, ed, emphasized between two "blood broth Anthl'Opology and Homosexual Behav ers" or two women friends, this allowed a ior, New York: Haworth Press, 1986, pp. context in which private homosexual 35-54; Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty, Women, Androgynes, and Other behavior could occur without attracting Mythical Beasts, Chicago: University of attention. -

Short Tender Call Notice

SHORT TENDER CALL NOTICE Sealed tender are invited for purchase of Books (Oriya and English) on different subjects for Biju Patnaik State Police Academy, Bhubaneswar. The approximate quantity required is noted against each. Titles of books, names of the Publisher and Writers are available in the Tender document and in our Website www.bpspaorissa.gov.in. Sl.No Name of the item Quantity 1 Library Books 1000 Approx. The Tender Document may be obtained on payment of Rs.200/- between 11 AM to 4 PM on each working day from the Office of the undersigned at the address given below. Tender document can also be obtained by sending a self stamped (Rs.75.00) envelop of size not less than 35cm x 25cm along with a demand draft of Rs.200/- payable at Bhubaneswar drawn in favour of the Director, BPSPA-cum-I.G. of Police, Training, Orissa, Bhubaneswar.Details of the documents/ specification and requirements may be down loaded from the Website of BPSPA i.e www.bpspaorissa.gov.in and sent along with a DD of Rs 200/- payable at BBSR in favour of Director, BPSPA-cum-IGP.Trg Orissa, Bhubaneswar. Bids submitted otherwise than the manner prescribed in the Tender document shall be rejected. Tender Calling authority has right to accept or reject the tender (s) without assigning any reason thereof. 1. Date of sale of Tender Document - 21.02.2011 ( between 10 AM to 5 PM on working days) 2. Last date of sale of Tender documents – 28.02.2011 3. Last date of receipt of Tender documents – 28.02.2011 4. -

History • America's Greatest Hits Mp3, Flac, Wma

America History • America's Greatest Hits mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: History • America's Greatest Hits Country: US Style: Soft Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1839 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1690 mb WMA version RAR size: 1702 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 580 Other Formats: DXD XM MP1 AHX MP2 MMF WAV Tracklist Hide Credits A Horse With No Name 1 4:07 Drums – Kim HaworthPercussion – Ray Cooper I Need You 2 3:05 Drums – Dave Atwood Sandman 3 3:58 Drums – Dave Atwood Ventura Highway 4 3:32 Drums, Percussion – Hal Blaine Don't Cross The River 5 2:30 Banjo – Henry Diltz Only In Your Heart 6 3:14 Drums, Percussion – Hal Blaine Muskrat Love 7 3:05 Congas – Chester McCracken* 8 Tin Man 3:26 9 Lonely People 2:27 10 Sister Golden Hair 3:20 11 Daisy Jane 3:07 12 Woman Tonight 2:25 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Copyright (c) – Warner Bros. Records Inc. Manufactured By – WEA Manufacturing Credits Arranged By – George Martin (tracks: 8 to 12) Art Direction – Ed Thrasher Bass – David Dickey (tracks: 7, 10 to 12), Joe Osborne* (tracks: 4 to 6) Design [Cover] – Phil Hartmann* Drums, Percussion – Willie Leacox (tracks: 8 to 12) Engineer – Geoff Emerick (tracks: 8 to 12), Ken Scott (tracks: 2, 3), Mike Stone (tracks: 4 to 7), Robin Black (tracks: 1) Engineer [Assistant] – Chuck Leary (tracks: 4 to 6), Lee Kiefer (tracks: 7), Tom Anderson (tracks: 10 to 12) Management [Direction] – Hartmann & Goodman Mixed By – George Martin (tracks: 1 to 7) Performer – Dan Peek, Dewey Bunnell, Gerry Beckley -

Emissions Gap

Emissions Gap Emissions Gap Report 2020 © 2020 United Nations Environment Programme ISBN: 978-92-807-3812-4 Job number: DEW/2310/NA This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations Environment Programme would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Communication Division, United Nations Environment Programme, P. O. Box 30552, Nairobi 00100, Kenya. Disclaimers The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For general guidance on matters relating to the use of maps in publications please go to http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/ htmain.htm Mention of a commercial company or product in this document does not imply endorsement by the United Nations Environment Programme or the authors. The use of information from this document for publicity or advertising is not permitted. Trademark names and symbols are used in an editorial fashion with no intention on infringement of trademark or copyright laws. -

Bhakti: a Bridge to Philosophical Hindus

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2000 Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus N. Sharath Babu Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Babu, N. Sharath, "Bhakti: A Bridge to Philosophical Hindus" (2000). Dissertation Projects DMin. 661. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/661 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS by N. Sharath Babu Adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: BHAKTI: A BRIDGE TO PHILOSOPHICAL HINDUS Name of researcher: N. Sharath Babu Name and degree of faculty adviser: Nancy J. Vyhmeister, Ed.D. Date completed: September 2000 The Problem The Christian presence has been in India for the last 2000 years and the Adventist presence has been in India for the last 105 years. Yet, the Christian population is only between 2-4 percent in a total population of about one billion in India. Most of the Christian converts are from the low caste and the tribals. Christians are accused of targeting only Dalits (untouchables) and tribals. Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the nation, advised Christians to direct conversion to those who can understand their message and not to the illiterate and downtrodden. -

2015 Draper Days Schedule of Events and Draper Park Map Draper City

2015 Draper Days Schedule of Events and Draper Park Map www.draperdays.org Draper City Summer is in full swing and you will want to make sure our city’s your car in the car show or your dog in the splash dogs competition, and on largest event, Draper Days 2015, is on your calendar. This event is Saturday evening see the impressive fireworks display. I would like to thank brought to you by the City of Draper and the Draper Community the Draper Days committee for all their hard work organizing this event and Foundation, as well as the many sponsors who help to make this working so hard to make this event so exciting and fun to attend. I will be event such a huge success. This year, we have two evenings of free there with my family, so say: “Howdy!” concerts featuring the band “America” and western singer “Collin Raye.” Plan to bring your family, friends and neighbors to partici- Sincerely, pate in the activities and events. This is an opportunity to get out in the summer sun, listen to an outdoor concert, see a rodeo and a Mayor Troy K. Walker parade, participate in a 5K race or a basketball tournament, enter FREE FIREWORKS BRING FAMILY The Perfect Edi to er Dys SPECTACULAR & FRIENDS SATURDAY NIGHT 2015 DraperDRAPER Days NIGHTS idySchedule Niht of Events Event Locations Sturdy Niht Draper Equestrian Center, 1266 E. 13400 So. www.draperdays.org Draper City Park, 1300 E 12500 South Draper Historic Park, 12625 South 900 East Draper Amphitheater, 944 E. -

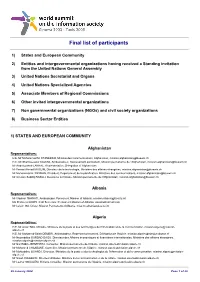

Final List of Participants

Final list of participants 1) States and European Community 2) Entities and intergovernmental organizations having received a Standing invitation from the United Nations General Assembly 3) United Nations Secretariat and Organs 4) United Nations Specialized Agencies 5) Associate Members of Regional Commissions 6) Other invited intergovernmental organizations 7) Non governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations 8) Business Sector Entities 1) STATES AND EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Afghanistan Representatives: H.E. Mr Mohammad M. STANEKZAI, Ministre des Communications, Afghanistan, [email protected] H.E. Mr Shamsuzzakir KAZEMI, Ambassadeur, Representant permanent, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Mr Abdelouaheb LAKHAL, Representative, Delegation of Afghanistan Mr Fawad Ahmad MUSLIM, Directeur de la technologie, Ministère des affaires étrangères, [email protected] Mr Mohammad H. PAYMAN, Président, Département de la planification, Ministère des communications, [email protected] Mr Ghulam Seddiq RASULI, Deuxième secrétaire, Mission permanente de l'Afghanistan, [email protected] Albania Representatives: Mr Vladimir THANATI, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Ms Pranvera GOXHI, First Secretary, Permanent Mission of Albania, [email protected] Mr Lulzim ISA, Driver, Mission Permanente d'Albanie, [email protected] Algeria Representatives: H.E. Mr Amar TOU, Ministre, Ministère de la poste et des technologies -

2015 STREET DATES JULY 31 AUGUST 7 Orders Due July 3 Orders Due July 10 7/28/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

ISSUE 16 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com NEW RELEASE GUIDE 2015 STREET DATES JULY 31 AUGUST 7 Orders Due July 3 Orders Due July 10 7/28/15 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Mama's Family: Mama's Favorites: Mama's Family TL DV 610583502497 31003-X $12.95 7/3/15 Season 6 (DVD) Last Update: 06/08/15 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Mama's Family TITLE: Mama's Family: Mama's Favorites: Season 6 (DVD) Label: TL/Time Life/WEA Config & Selection #: DV 31003 X Street Date: 07/28/15 Order Due Date: 07/03/15 UPC: 610583502497 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $12.95 Alphabetize Under: M ALBUM FACTS Genre: Television Packaging Specs: Single DVD; Running Time: 129 minutes Description: MAMA’S FAMILY: THE BEST OF SEASON SIX In the world of prime-time television, success often begets success by way of the spin-off. The Carol Burnett Show lasted eleven seasons on CBS, thanks in part to the recurring comedy sketches that attracted a large, loyal viewership. “The Family” remained a favorite because fans related to the Harpers’ constant squabbling about mundane stuff. As the irascible Mama Harper, Vicki Lawrence was wondrously transformed into a full-tilt senior citizen and it wasn’t a matter of if, but when, she would get her own TV series. MAMA’S FAMILY debuted in 1983 on NBC, lasting two seasons before going into syndication for another four years.