Examining Slavery's Architectural Finishes: the Importance of Interdisciplinary Investigations of Humble Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement

KASAI UK LTD Gender Pay Report At Kasai we are committed to treating our people equally and ensuring that everyone – no matter what their background, race, ethnicity or gender – has an opportunity to develop. We are confident that our gender pay gap is not caused by men and woman being paid differently to do the same job but is driven instead by the structure of our workforce which is heavily male dominated. As of the snapshot date the table below shows our overall mean and median gender pay gap and bonus pay based on hourly rates of pay. Difference between men and woman Mean (Average) Median (Mid-Range) Hourly Pay Gap 18.1% 20.9% Bonus Pay Gap 0% 0% Quartiles We have divided our population into four equal – sized pay quartiles. The graphs below show the percentage of males and females in each of these quartiles Upper Quartiles 94% males 6% females -5.70% Upper middle quartiles 93% male 7% females -1.30% Lower middle quartiles 87% male 13% females 2.39% Lower Quartiles 76% male 24% females 3.73% Analysis shows that any pay gap does not arise from male and females doing the same job / or same level and being paid differently. Females and males performing the same role and position, have the same responsibility and parity within salary. What is next? We are confident that our male and female employees are paid equally for doing equivalent jobs across our business. We will continue to monitor gender pay throughout the year. Flexible working and supporting females through maternity is a key enabler in retaining and developing female’s talent in the future business. -

Harry-Potter-Clue-Rules.Pdf

AGES 9+ 3-5 Players shows the Dark Mark – take a Check this card off on your 5. Make an Accusation card from the Dark Deck and If all players run out of house • If you are in a room at the notepad – this proves the How to Play – read it out loud. points before the game is end of one turn, you must card is not in the envelope. When you’re sure you’ve solved At a Glance over, the Dark Forces have leave it on your next turn. Your turn is now over. the mystery, use your roll to get Each Dark card describes won and the missing student You may not re-enter the to Dumbledore’s office as fast as On each turn: an event likely to have been meets an unfortunate end! same room on that turn. • If the player to your left does you can. From here, you can make caused by Dark Forces and each not have any of the Mystery your accusation by naming the 1. Roll card shows: • You cannot pass through a cards you suggested, the player suspect, item and location you 3. Move closed door unless you have to their left must show a card think are correct. For example: 2. Check the Hogwarts die • What is happening an Alohomora Help card. if they have one. Keep going 3. Move (using the other dice Check the two normal dice. until a player shows you a “I accuse Dolores Umbridge with or a secret passage) • Who is affected You can either: card or until all players have the Sleeping Draught in the Great 4. -

Religion of the South” and Slavery Selections from 19Th-Century Slave Narratives

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 ON THE “RELIGION OF THE SOUTH” AND SLAVERY SELECTIONS FROM 19TH-CENTURY SLAVE NARRATIVES * In several hundred narratives, many published by abolitionist societies in the U.S. and England, formerly enslaved African Americans related their personal experiences of enslavement, escape, and freedom in the North. In straight talk they condemned the “peculiar institution” ⎯ its dominance in a nation that professed liberty and its unyielding defense by slaveholders who professed Christianity. “There is a great difference between Christianity and religion at the south,” writes Harriet Jacobs; Frederick Douglass calls it the “the widest, possible difference ⎯ so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked.”1 Presented here are four nineteenth-century African American perspectives on the “religion of the south.” Frederick Douglass “the religion of the south . is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes” I assert most unhesitatingly that the religion of the south ⎯ as I have observed it and proved it ⎯ is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes, the justifier of the most appalling barbarity, a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds, and a secure shelter under which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal abominations fester and flourish. Were I again to be reduced to the condition of a slave, next to that calamity, I should regard the fact of being the slave of a religious slaveholder the greatest that could befall me. For of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19Th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2017 The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia Julianna Geralynn Jackson College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Julianna Geralynn, "The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia" (2017). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1516639577. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/S2V95T This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Octagon House and Mount Airy: Exploring the Intersection of Slavery, Social Values, and Architecture in 19th-Century Washington, DC and Virginia Julianna Geralynn Jackson Baldwin, Maryland Bachelor of Arts, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, 2012 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of The College of William & Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of William & Mary August, 2017 © Copyright by Julianna Geralynn Jackson 2017 ABSTRACT This project uses archaeology, architecture, and the documentary record to explore the ways in which one family, the Tayloes, used Georgian design principals as a way of exerting control over the 19th-century landscape. -

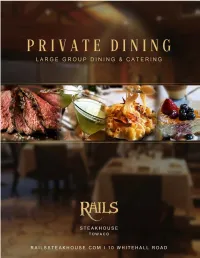

Private Dining [email protected]

LARGE GROUP DINING & CATERING Pat Leone, Director of Private Dining [email protected] Rails Steakhouse 10 Whitehall Road Towaco, NJ 07082 973.487.6633 cell / text 973.335.0006 restaurant 2 Updated 8/2/2021 PRIVATE DINI NG P L A N N I N G INFORMATION RAILS STEAKHOUSE IS LOCATED IN MORRIS COUNTY IN THE HEART ROOM ASSIGNMENTS OF MONTVILLE TOWNSHIP AND RANKS AMONG THE TOP ROOMS ARE RESERVED ACCORDING TO THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE STEAKHOUSES IN NEW JERSEY. RAILS IS KNOWN FOR USDA PRIME ANTICIPATED AT THE TIME OF THE BOOKING. ROOM FEES ARE AND CAB CORN-FED BEEF, DRY-AGED 28-30 DAYS ON PREMISE IN APPLICABLE IF GROUP ATTENDANCE DROPS BELOW THE ESTIMATED OUR DRY AGING STEAK ROOM, AND AN AWARD WINNING WINE ATTENDANCE AT THE TIME OF BOOKING. RAILS RESERVES THE LIST RECOGNIZED BY WINE SPECTATOR FIVE CONSECTUTIVE YEARS. RIGHT TO CHANGE ROOMS TO A MORE SUITABLE SIZE, WITH NOTIFICATION, IF ATTENDANCE DECREASES OR INCREASES. DINING AT RAILS THE INTERIOR DESIGN IS BREATHTAKING - SPRAWLING TIMBER, EVENT ARRANGEMENTS NATURAL STONE WALLS, GLASS ACCENTS, FIRE AND WATER TO ENSURE EVERY DETAIL IS HANDLED IN A PROFESSIONAL FEATURES. GUESTS ARE INVITED TO UNWIND IN LEATHER MANNER, RAILS REQUIRES THAT YOUR MENU SELECTIONS AND CAPTAIN'S CHAIRS AND COUCHES THAT ARE ARRANGED TO INSPIRE SPECIFIC NEEDS BE FINALIZED 3 WEEKS PRIOR TO YOUR FUNCTION. CONVERSATION IN ONE OF THREE LOUNGES. AT THAT POINT YOU WILL RECEIVE A COPY OF OUR BANQUET EVENT ORDER ON WHICH YOU MAY MAKE ADDITIONS AND STROLL ALONG THE CATWALK AND EXPLORE RAFTER'S LOUNGE DELETIONS AND RETURN TO US WITH YOUR CONFIRMING AND THE MOSAIC ROOM. -

Three Cranes Tavern (1629-1775) Charlestown, Massachsuetts

David Teniers “Tavern Scene” 1658 An Archaeological Reevaluation of the Great House/ Three Cranes Tavern (1629-1775) Charlestown, Massachsuetts By Craig S. Chartier Plymouth Archaeological Rediscovery Project May 2016 Citizens of the Commonwealth were given a rare opportunity to witness the investigation of part of Boston's earliest colonial past during the city's "Big Dig"/ Central Artery Project in 1985, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony's "Great House" was explored prior to the site's destruction (all of the background information presented here, on both the history of the property and the excavations, is based on Gallagher et al 1994). The Great House, located in City Square in Charlestown, was built in 1629 before Boston was even settled. It was to serve as the first residence of Governor Winthrop and the other prominent members of the company and as the colony's meetinghouse. It is believed to have been erected by a party of 100 men from Salem, who had been sent with orders to build it, lay out streets, and survey the two acre lots to be assigned to settlers. Work was begun in June 1629 and was expected to be completed by the time of the arrival of Winthrop's fleet of 11 ships in the summer of the following year. Archaeologists assumed that it was to have been a formal, professionally designed structure symbolizing the hierarchical nature of the new settlement and serving as a link between the old and new worlds. Unfortunately, soon after the fleet's arrival, a great mortality swept the colony, which the settlers attributed to the brackish drinking water in the new settlement. -

The Edward Houstoun Plantation Tallahassee,Florida

THE EDWARD HOUSTOUN PLANTATION TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA INCLUDING A DISCUSSION OF AN UNMARKED CEMETERY ON FORMER PLANTATION LANDS AT THE CAPITAL CITY COUNTRY CLUB Detail from Le Roy D. Ball’s 1883 map of Leon County showing land owned by the Houstoun family.1 JONATHAN G. LAMMERS APRIL, 2019 adlk jfal sk dj fsldkfj Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 The Houstoun Plantation ................................................................................................................................. 2 Edward Houstoun ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Patrick Houstoun ........................................................................................................................................... 6 George B. Perkins and the Golf Course .................................................................................................. 10 Golf Course Expansion Incorporates the Cemetery .......................................................................... 12 The Houstoun Plantation Cemetery ............................................................................................................. 15 Folk Burial Traditions ................................................................................................................................. 17 Understanding Slave Mortality .................................................................................................................. -

The Difficult Plantation Past: Operational and Leadership Mechanisms and Their Impact on Racialized Narratives at Tourist Plantations

THE DIFFICULT PLANTATION PAST: OPERATIONAL AND LEADERSHIP MECHANISMS AND THEIR IMPACT ON RACIALIZED NARRATIVES AT TOURIST PLANTATIONS by Jennifer Allison Harris A Dissertation SubmitteD in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public History Middle Tennessee State University May 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Kathryn Sikes, Chair Dr. Mary Hoffschwelle Dr. C. Brendan Martin Dr. Carroll Van West To F. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot begin to express my thanks to my dissertation committee chairperson, Dr. Kathryn Sikes. Without her encouragement and advice this project would not have been possible. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my dissertation committee members Drs. Mary Hoffschwelle, Carroll Van West, and Brendan Martin. My very deepest gratitude extends to Dr. Martin and the Public History Program for graciously and generously funding my research site visits. I’m deeply indebted to the National Science Foundation project research team, Drs. Derek H. Alderman, Perry L. Carter, Stephen P. Hanna, David Butler, and Amy E. Potter. However, I owe special thanks to Dr. Butler who introduced me to the project data and offered ongoing mentorship through my research and writing process. I would also like to extend my deepest gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Douglass for her continued professional sponsorship and friendship. The completion of my dissertation would not have been possible without the loving support and nurturing of Frederick Kristopher Koehn, whose patience cannot be underestimated. I must also thank my MTSU colleagues Drs. Bob Beatty and Ginna Foster Cannon for their supportive insights. My friend Dr. Jody Hankins was also incredibly helpful and reassuring throughout the last five years, and I owe additional gratitude to the “Low Brow CrowD,” for stress relief and weekend distractions. -

Archaeology in Alberta 1978

ARCHAEOLOGY IN ALBERTA, 1978 Compiled by J.M. Hillerud Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper No. 14 ~~.... Prepared by: Published by: Archaeological Survey Alberta Culture of Alberta Historical Resources Division OCCASIONAL PAPERS Papers for publication in this series of monographs are produced by or for the four branches of the Historical Resources Division of Alberta Culture: the Provincial Archives of Alberta, the Provincial Museum of Alberta, the Historic Sites Service and the Archaeological Survey of Alberta. Those persons or institutions interested in particular subject sub-series may obtain publication lists from the appropriate branches, and may purchase copies of the publications from the following address: Alberta Culture The Bookshop Provincial Museum of Alberta 12845 - 102 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T5N OM6 Phone (403) 452-2150 Objectives These Occasional Papers are designed to permit the rapid dissemination of information resulting from Historical Resources' programmes. They are intended primarily for interested specialists, rather than as popular publications for general readers. In the interests of making information available quickly to these specialists, normal production procedures have been abbreviated. i ABSTRACT In 1978, the Archaeological Survey of Alberta initiated and adminis tered a number of archaeological field and laboratory investigations dealing with a variety of archaeological problems in Alberta. The ma jority of these investigations were supported by Alberta Culture. Summary reports on 21 of these projects are presented herein. An additional four "shorter contributions" present syntheses of data, and the conclusions derived from them, on selected subjects of archaeo logical interest. The reports included in this volume emphasize those investigations which have produced new contributions to the body of archaeological knowledge in the province and progress reports of con tinuing programmes of investigations. -

The Antebellum Houses of Hancock County, Georgia

PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA by CATHERINE DREWRY COMER (Under the Direction of Wayde Brown) ABSTRACT Antebellum houses are a highly significant and irreplaceable cultural resource; yet in many cases, various factors lead to their slow deterioration with little hope for a financially viable way to restore them. In Hancock County, Georgia, intensive cultivation of cotton beginning in the 1820s led to a strong plantation economy prior to the Civil War. In the twenty-first century, however, Hancock has been consistently ranked among the stateʼs poorest counties. Surveying known and undocumented antebellum homes to determine their current condition, occupancy, and use allows for a clearer understanding of the outlook for the antebellum houses of Hancock County. Each of the antebellum houses discussed in this thesis tells a unique part of Hancockʼs history, which in turn helps historians better understand a vanished era in southern culture. INDEX WORDS: Historic preservation; Log houses; Transitional architecture; Greek Revival architecture; Antebellum houses; Antebellum plantations; Hancock County; Georgia PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA By CATHERINE DREWRY COMER B.S., Southern Methodist University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Catherine Drewry Comer All Rights Reserved PRESERVING EARLY SOUTHERN ARCHITECTURE: THE ANTEBELLUM HOUSES OF HANCOCK COUNTY, GEORGIA by CATHERINE DREWRY COMER Major Professor: Wayde Brown Committee: Mark Reinberger Scott Messer Rick Joslyn Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my family and friends for supporting me throughout graduate school. -

Mcleod PLANTATION JAMES ISLAND Sa

FfO.1: 'lIIE HIS'lORIC CHARIES'lON FOUNDATION 'lO: WILLIS J. KEITH, JAMES IS. ,SC - 12 APRILI", 19~ HISTORIC S~Y FOR McLEOD PLANTATION JAMES ISLAND sa , . , . , 1,. ~ •• McLEOD PLANTATION Su.ozn.:i.tted By F:i.11~ore G. Wi1son Me~dors Constru.ction Corpor~t:i.on Apr i 1 1 6.. 1 99:3 , '. t , --------- OWNERSHIP CHAIN ._-_........ OWNERSHIP CHAIN McLEOD PLANTATION ) Thornton-Morden map, The Thornton-Morden map of 1695 shows the South Carolina property on which the McLeod Plantation Historical Society, would be situated as belonging to Morris. Charleston, S.C.; The Morris on the map is probably Morgan James P. Hayes, Morris who came to James Island from James and Related Virginia in December, 1671. Sea Islands, (Charleston: Walker Evans & Cogswell Company, 1978), 7. Royal Grants # 0002 In 1703 Captain Davis received a grant 005-0038-02, South from the Lords Proprietors for a plot of Carolina Archives land on James island containing 617 acres. The land was bounded generally by : N: Wappoo Creek and the marsh of the Ashley River S: Partly by New Town Creek and partly by the land laid out to Richard Simpson. W: Lands of M. Shabishere E: The marsh of New Town Creek Charleston Deeds In 1706 Captain Davis and his wife Ann #0007-001-00S0 sold their land to William Wilkins. 00435-00, 1737-1739, William Wilkins sold the land several South Carolina times and repurchased it each time until Department of 1741. Archives and History, Columbia, S.C. 1 Charleston Deeds, On April 14, 1741, William Wilkins and Vol.