128300853.23.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addendum: University of Nottingham Letters : Copy of Father Grant’S Letter to A

Nottingham Letters Addendum: University of 170 Figure 1: Copy of Father Grant’s letter to A. M. —1st September 1751. The recipient of the letter is here identified as ‘A: M: —’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 171 Figure 2: The recipient of this letter is here identified as ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 172 Figure 3: ‘Key to Scotch Names etc.’ (NeC ¼ Newcastle of Clumber Mss.). Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. 173 Figure 4: In position 91 are the initials ‘A: M: —,’ which, according to the information in NeC 2,089, corresponds to the name ‘Alexander Mc Donell of Glengarry Esqr.’, are on the same line as the cant name ‘Pickle’. Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottinghan. Notes 1 The Historians and the Last Phase of Jacobitism: From Culloden to Quiberon Bay, 1746–1759 1. Theodor Fontane, Jenseit des Tweed (Frankfurt am Main, [1860] 1989), 283. ‘The defeat of Culloden was followed by no other risings.’ 2. Sir Geoffrey Elton, The Practice of History (London, [1967] 1987), 20. 3. Any subtle level of differentiation in the conclusions reached by participants of the debate must necessarily fall prey to the approximate nature of this classifica- tion. Daniel Szechi, The Jacobites. Britain and Europe, 1688–1788 (Manchester, 1994), 1–6. -

Fact Or Fiction?

Hugvísindasvið Fact or Fiction? An Examination of Historical Accuracy in John Buchan’s A Lost Lady of Old Years and an Assessment of Buchan’s Influences Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Kristjana Hrönn Árnadóttir May 2012 University of Iceland School of Humanities Department of English Fact or Fiction? An Examination of Historical Accuracy in John Buchan’s A Lost Lady of Old Years and an Assessment of Buchan’s Influences Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Kristjana Hrönn Árnadóttir Kt.: 09.02.87-2499 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir May 2012 Abstract This essay is an examination of the Scottish writer John Buchan (1875-1941) and his historical novel A Lost Lady of Old Years which was published in 1899. The thesis has two main purposes; the first is to examine the historicity of the novel and how Buchan makes use of historical events while creating his characters and storyline. The second objective of the dissertation is to examine Buchan’s goals and inspirations while writing the novel, where his influences come from and why he wrote the book, his aims of education and of entertainment. It will assess the effect writers like Robert Louis Stevenson and Sir Walter Scott had on Buchan’s writing and then considers how Buchan’s upbringing and personal opinions appear in the novel. Part I: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 Part II: Background ......................................................................................................... 1 2.1 John Buchan .................................................................................................... -

Cycle Route 10

ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE STARTING POINT OathlawOathlaw N Forfar Loch Country Park AberlemnoAberlemno GRADE Moderate LENGTH PitkennedyPitkennedy 41km/25 miles APPROXIMATE TIME DubtonDubton 4-5 hours LunanheadLunanhead OS MAP RescobieRescobie 54 (Dundee & Montrose) ReswallieReswallie BalgaviesBalgavies START FORFARFORFAR MilldensMilldens GuthrieGuthrie BurnsideBurnside PitmuiesPitmuies KingsmuirKingsmuir DunnichenDunnichen LethamLetham CaldhameCaldhame IdivesIdives CraichieCraichie CYCLE ROUTE 00.71.42.1 KM © Crown copyright and database right 2021. All rights reserved. 100023404. ANGUS CYCLING ROUTES Forfar, Aberlemno and Letham Circuit 10 ROUTE ROUTE DESCRIPTION A varied and entertaining ride that visits a number of historical sites. Starting at Forfar Loch Country Park, turn right and then take an immediate left onto Manor Street. Turn right onto Castle Street and then turn left at the T junction to Arbroath. Go straight on at the traffic lights and bear left to Brechin. Continue for 8.1km/4.9m to Aberlemno to visit the Pictish stones opposite the school. Retrace the route and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy after 100 metres. Continue for 0.9km/0.6m and turn left at the sign for Pitkennedy. Turn left again after 0.1km. Continue for 2.8km/1.7m and turn left at the T junction. After 1km/0.6m, turn right. After a further 1km/0.6m, turn right at the T junction. After 4.1km/2.5m, go straight on at the crossroads crossing the B9113 to Balgavies. Turn right after 1.6km/1m. Turn right again at the T junction on to the A932. At the sign for Trumperton Tea Room, turn left. -

1 Update Report on the Winning Years Prepared for the Scottish

Update Report on The Winning Years Prepared for the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee 9 September 2013 INTRODUCTION This report updates the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee on the activity and results from The Winning Years; eight milestones over three years which VisitScotland and partners have been promoting to, and working with, the tourism industry on. The overall ambition behind the development of the Winning Years concept is to ensure that the tourism industry and wider visitor economy is set to take full advantage of the long-term gains over the course of the next few years. The paper is divided into sections covering each of the milestones: Year of Creative Scotland The 2012 London Olympics The Diamond Jubilee Disney.Pixar’s Brave Year of Natural Scotland The Commonwealth Games The 2014 Ryder Cup Homecoming Scotland 2014 (incl. up to date list of events) From this report Committee members will see that excellent progress has been made, with strong interest in Scotland’s tourism product from around the world as the country builds to welcome the world in 2014. All of this despite the continuing global economic difficulties. Evidence of bucking the global trend and the success of the 2012 Winning Years milestones can be seen in VisitScotland’s announcement at the end of August that its two main marketing campaigns brought nearly £310m additional economic benefit for Scotland since January 2012. This is a rise of 14% on the same period the year before. VisitScotland’s international campaigns target Scotland’s main markets across the globe including North America, Germany and France as well as emerging markets, such as India and China. -

The Leaflet Made a Trip Across to Rosedale (Bateman’S Bay) to See Anne Coutts

T HE L EAFLET --- April 2018 Other news Whilst visiting Canberra in January, Jenny and Wallace Young The Leaflet made a trip across to Rosedale (Bateman’s Bay) to see Anne Coutts. Her late husband, Laurence, was Assistant Minister at No. 1069 Scots’ Church from 1994-96, and many members have fond April 2018 memories of their time amongst us. Late last year Anne had major surgery, but is well on the way to recovery, and sends her greetings to all. Anne Coutts with her rescue dog Charlie William Mackie, grandson of Gordon and Lois Taylor, has recently completed a major project for his Australian Scout Medallion (pictured). William will travel to Sydney in August for the presentation of the award, the highest in Scouting. Well done William! William Mackie with his Australian Scout Medallion project Welcome back to all those who have had holidays in Australia or further afield in recent weeks. As each edition of The Leaflet goes to print we are aware that some of our members are suffering from illness, both in their immediate families or amongst close friends. If you are unable to be with us rest assured that all members of the Scots’ Church family are held in our prayers, and we are just a phone call away if we can help. Lois Taylor A0538 Scots Leaflet Dec16 cover printready.indd Sec1:44 25/11/2016 7:40:40 AM A0538 Scots Leaflet Dec16 cover printready.indd forei 25/11/2016 7:40:25 AM A0538 Scots Leaflet Dec16 cover printready.indd Sec1:44 25/11/2016 7:40:40 AM A0538 Scots Leaflet Dec16 cover printready.indd forei 25/11/2016 7:40:25 AM THE -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) -

Scotland – North

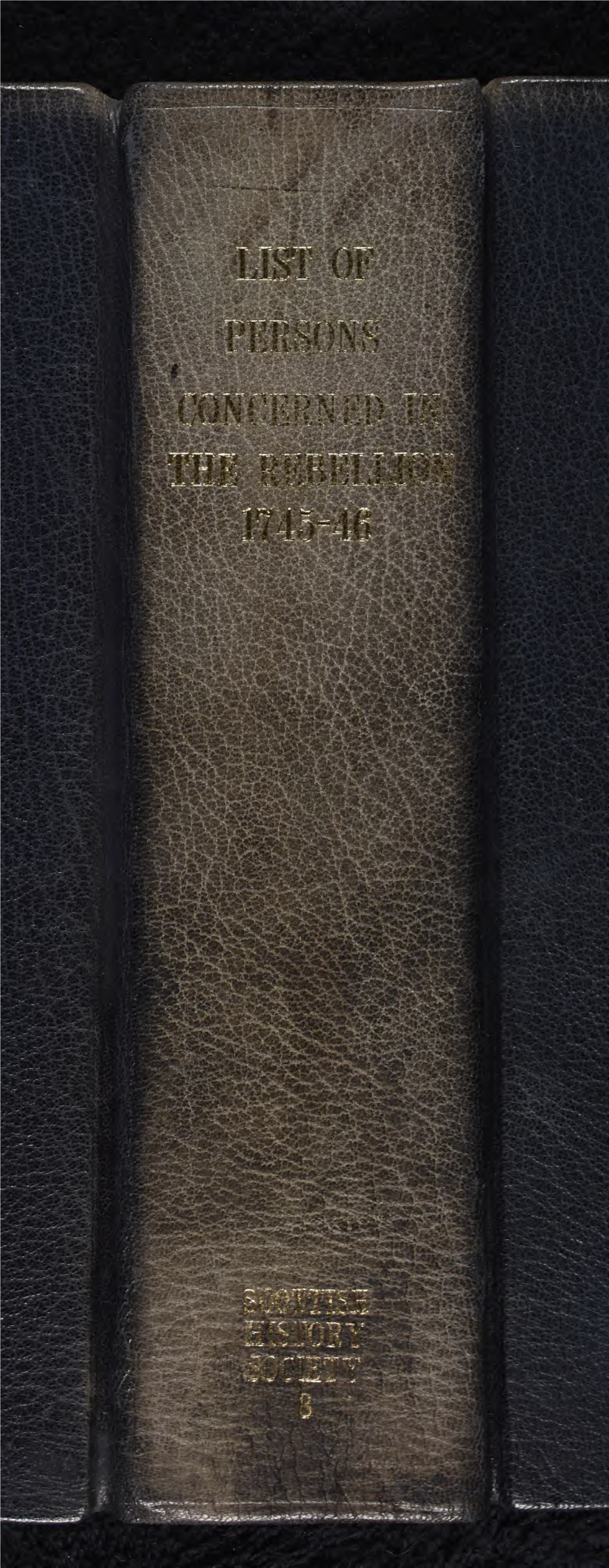

Scotland – North Scotland was at the heart of Jacobitism. All four Jacobite risings - in 1689-91, 1715-16, 1719 and 1745-46 - took place either entirely (the first and third) or largely (the second and fourth) in Scotland. The north of Scotland was particularly important in the story of the risings. Two of them (in 1689-91 and 1719) took place entirely in the north of Scotland. The other two (in 1715-16 and 1745-46) began and ended in the north of Scotland, although both had wider theatres during the middle stages of the risings. The Jacobite movement in Scotland managed to attract a wide range of support, which is why more than one of the risings came close to succeeding. This support included Lowlanders as well as Highlanders, Episcopalians as well as Catholics (not to mention some Presbyterians and others), women as well as men, and an array of social groups and ages. This Scotland-North section has many Jacobite highlights. These include outstanding Jacobite collections in private houses such as Blair Castle, Scone Palace and Glamis Castle; state-owned houses with Jacobite links, such as Drum Castle and Corgarff Castle; and museums and exhibitions such as the West Highland Museum and the Culloden Visitor Centre. They also include places which played a vital role in Jacobite history, such as Glenfinnan, and the loyal Jacobite ports of the north-east, and battlefields (six of the land battles fought during the risings are in this section, together with several other skirmishes on land and sea). The decision has been made here to divide the Scottish sections into Scotland – South and Scotland – North, rather than the more traditional Highlands and Lowlands. -

Journal of the Scottish Parliament Volume 2: 2Nd Parliamentary Year

Journal of the Scottish Parliament Volume 2: 2nd Parliamentary Year, Session 3 (9 May 2008 – 8 May 2009) SPJ 3.2 © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body Information on the Scottish Parliament’s copyright policy can be found on the website - www.scottish.parliament.uk or by contacting Public Information on 0131 348 5000. Foreword The Journal is the central, long-term, authoritative record of what the Parliament has done. The Minutes of Proceedings, which are produced for each meeting of the Parliament, do that in an immediate way, while the Journal presents essentially the same material but has the benefit of hindsight to allow any errors and infelicities of presentation to be corrected. Unlike the Official Report, which primarily records what is said, the Minutes of Proceedings, and in the longer term the Journal, provide the authoritative record of what was done. The Journal is required under Rule 16.3 of Standing Orders and contains, in addition to the Minutes of Proceedings themselves, notice of any Bill introduced*, notice of any instrument or draft instrument or any other document laid before the Parliament; notice of any report of a committee, and any other matter that the Parliament, on a motion of the Parliamentary Bureau, considers should be included. (* The requirement to include notice of Bills introduced was only added to Rule 16.3 in January 2003. However, such notices have in practice been recorded in the Annex to the Minutes of Proceedings from the outset.) Note: (DT), which appears throughout the Journal, signifies a decision taken at Decision Time. -

The Parish of Durris

THE PARISH OF DURRIS Some Historical Sketches ROBIN JACKSON Acknowledgments I am particularly grateful for the generous financial support given by The Cowdray Trust and The Laitt Legacy that enabled the printing of this book. Writing this history would not have been possible without the very considerable assistance, advice and encouragement offered by a wide range of individuals and to them I extend my sincere gratitude. If there are any omissions, I apologise. Sir William Arbuthnott, WikiTree Diane Baptie, Scots Archives Search, Edinburgh Rev. Jean Boyd, Minister, Drumoak-Durris Church Gordon Casely, Herald Strategy Ltd Neville Cullingford, ROC Archives Margaret Davidson, Grampian Ancestry Norman Davidson, Huntly, Aberdeenshire Dr David Davies, Chair of Research Committee, Society for Nautical Research Stephen Deed, Librarian, Archive and Museum Service, Royal College of Physicians Stuart Donald, Archivist, Diocesan Archives, Aberdeen Dr Lydia Ferguson, Principal Librarian, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Harper, Durris, Kincardineshire Nancy Jackson, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Katy Kavanagh, Archivist, Aberdeen City Council Lorna Kinnaird, Dunedin Links Genealogy, Edinburgh Moira Kite, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire David Langrish, National Archives, London Dr David Mitchell, Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Margaret Moles, Archivist, Wiltshire Council Marion McNeil, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Effie Moneypenny, Stuart Yacht Research Group Gay Murton, Aberdeen and North East Scotland Family History Society, -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Diocese in Europe Prayer Diary, July to December 2011

DIOCESE IN EUROPE PRAYER DIARY, JULY TO DECEMBER 2011 This calendar has been compiled to help us to pray together for one another and for our common concerns. Each chaplaincy, with the communities it serves, is remembered in prayer once a year, according to the following pattern: Eastern Archdeaconry - January, February Archdeaconry of France - March, April Archdeaconry of Gibraltar - May, June Diocesan Staff - July Italy & Malta Archdeaconry - July Archdeaconry of North West Europe - August, September Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe Nordic and Baltic Deanery - September, October Germany - November Swiss Archdeaconry - November, December Each Archdeaconry, with its Archdeacon, is remembered on a Sunday. On the other Sundays, we pray for subjects which affect all of us (e.g. reconciliation, on Remembrance Sunday), or which have local applications for most of us (e.g. the local cathedral or cathedrals). Some chaplains might like to include prayers for the other chaplaincies in their deanery. We also include the Anglican Cycle of Prayer (daily, www.aco.org), the World Council of Churches prayer cycle (weekly, www.oikoumene.org, prayer resources on site), the Porvoo Cycle (weekly, www.porvoochurches.org), and festivals and commemorations from the Common Worship Lectionary (www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts.aspx). Sundays and Festivals, printed in bold type, have special readings in the Common Worship Lectionary. Lesser Festivals, printed in normal type, have collects in the Common Worship Lectionary. Commemorations, printed in italics, may have collects in Exciting Holiness, and additional, non- biblical, readings for all of these may be found in Celebrating the Saints (both SCM-Canterbury Press).