I the Modernization of Honor in Eighteenth-Century Political Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duke Staff Handbook

DUKE STAFF HANDBOOK “…itisuptoustoset anexampleofhowa communityofpeople workingtogethertoward acommonpurpose canrealizeoutrageous ambitions.” VincentE.Price President Checkout ,~,_ UKE forthelatestnews,resources&conversation Print: Working@Dukepublication Online:working.duke.edu Facebook:facebook.com/workingatduke 0 Twitter: twitter.com/workingatduke WELCOME TO DUKE As President, it is my pleasure to welcome you to Duke! Duke’s employees are among the university’s greatest strengths. When you work here, you don’t just do the job and go home. You’re part of the campus community. You share in the university’s successes and help define its identity. Former president Terry Sanford perhaps put it best: every person who works for Duke is important to Duke; they are all Duke University People. As a new Duke University Person, you should take some time to familiarize yourself with this handbook, which is intended to help you establish a successful working relationship with the Duke community. It outlines the many resources and opportunities that are available to you as an employee, and it should help you understand what Duke expects from you as a staff member and what you should expect from Duke. You can find answers to additional questions by reviewing the Duke Human Resources Policy Manual (hr.duke.edu/policies) or by speaking with your supervisor. I also invite you to share in the responsibility of shaping the university’s identity and guiding it toward a more inclusive future. Duke is about much more than what happens in the classroom or the lab; it is up to us to set an example of how a community of people working together toward a common purpose can realize outrageous ambitions. -

SCHEDULE of JOURNEYS COSTING £10,000 OR MORE Year Ended 31St March 2015

SCHEDULE OF JOURNEYS COSTING £10,000 OR MORE Year Ended 31st March 2015 Household Method Date Itinerary Cost (£) of travel The Queen and The Duke of Charter 3 Apr NHT – Rome - NHT 27,298 Edinburgh Visit The President of the Italian Republic and Mrs. Napolitano at Quirinale Palace. Visit The Sovereign of the State of the Vatican City (His Holiness Pope Francis). The Prince of Wales Royal 8-9 Apr Windsor - Oxenholme 17,772 Train Visit J36 Rural Auction Centre. Attend the launch of the Tourism Initiative. Visit the Northern Fells Group Rural Revival Initiative. Visit Hospice at Home West Cumbria. The Queen and The Duke of Royal 16-17 Apr Windsor - Blackburn 17,551 Edinburgh Train Attend the Maundy Service at which Her Majesty distributed the Royal Maundy. Join representatives of the Cathedral, the Diocese and the Royal Almonry at a Reception at Blackburn Rovers Football Club, Ewood Park. Luncheon at the Club by the Mayor of Blackburn-with-Darwen. Staff (Prince Henry of Wales) Scheduled 27 Apr - 1 LHR – Sao Paulo - Santiago - Brasilia – 19,304 Flight May Belo Horizonte – Sao Paul – LHR Reconnaissance tour for Prince Henry of Wales visit to Brazil and Chile. The Queen and The Duke of Royal 29-30 Apr Windsor - Haverfordwest - Ystrad Mynach 30,197 Edinburgh Train Visit Cotts Equine Centre, Cotts Farm, Narberth. Tour the equine hospital, view the "Knock Down and Recovery Suite", Operating Theatre, Nurses' Station and horses, and meet members of the veterinary team, grooms and other staff members. Visit Princes Gate Spring Water, New House Farm, Narberth. Luncheon at Picton Castle, Haverfordwest by Pembrokeshire County Council. -

The Heir Presumptive and the Heir Apparent

THE HEIR PRESUMPTIVE THE HEIR APPARENT MRS. OLIPHANT author of "for loVe and life," "a country gentleman," etC. etc. IN THREE VOLUMES VOL. Ill MACMILLAN & CO. AND NEW YORK 1892 chArlES DicKenS AnD EVAnS, crYStal PAlAcE PRESS. THE HEIR PRESUMPTIVE AND THE HEIR APPARENT CHAPTER I When Agnes went upstairs after this genial but interrupted meal she was met by her sister's maid, who begged her to go at once to Lady Frogmore. " My lady's very restless," said the attendant, who was something more than a maid, the same who had brought her home after her recovery. " You don't think there's anything wrong ? " said Agnes, breathless, for notwithstanding the tranquillity of so many years, any trifle was enough to rouse her anxieties. " Oh, I hope not," said the maid. This was enough, it need not be said, to VOL. III. B THE HEIR PRESUMPTIVE send Miss Hill trembling to her sister's side. Mary was lying very quietly in bed, with some boxes on the table beside her, and a miniature of her husband, which she always carried about with her, in her hands. " You wanted me, Mary ? " " No," said Lady Frogmore gently ; then, after a pause : " Yes ; I hope you will not be disappointed, dear Agnes ; I think I must go home." " Home ! but we came for Duke's party." " I know ; but I do not think I can remain any longer. Perhaps if you were to stay " " I will not stay if you go, Mary." " I thought Letitia would not mind so much if one of us was here. -

Titles – a Primer

Titles – A Primer The Society of Scottish Armigers, INC. Information Leaflet No. 21 Titles – A Primer The Peerage – There are five grades of the peerage: 1) Duke, 2) Marquess, 3) Earl, 4) Viscount and 5) Baron (England, GB, UK)/Lord of Parliament (Scotland). Over the centuries, certain customs and traditions have been established regarding styles and forms of address; they follow below: a. Duke & Duchess: Formal style: "The Most Noble the Duke of (title); although this is now very rare; the style is more usually, “His Grace the Duke of (Hamilton), and his address is, "Your Grace" or simply, "Duke” or “Duchess.” The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. Younger sons use "Lord" followed by their first name (e.g., Lord David Scott); daughters are "Lady" followed by their first name (e.g., Lady Christina Hamilton); in conversation, they would be addressed as Lord David or Lady Christina. The same rules apply to eldest son's sons and daughters. The wife of a younger son uses”Lady” prior to her husbands name, (e.g. Lady David Scot) b. Marquess & Marchioness: Formal style: "The Most Honourable the Marquess/Marchioness (of) (title)" and address is "My Lord" or e.g., "Lord “Bute.” Other rules are the same as dukes. The eldest son, by courtesy, uses one of his father’s subsidiary titles. Wives of younger sons as for Dukes. c. Earl & Countess: Formal style: "The Right Honourable the Earl/Countess (of) (title)” and address style is the same as for a marquess. The eldest son uses one of his father's subsidiary titles as a courtesy. -

Biography of His Royal Highness the Grand Duke

Biography of His Royal Highness the Grand Duke His Royal Highness Grand Duke Henri was born on 16 April 1955 at Betzdorf Castle in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Grand Duke Henri, Prince of Nassau, Prince of Bourbon-Parma, is the eldest son of the five children of Grand Duke Jean and Grand Duchess Joséphine-Charlotte. On 14 February 1981, the Hereditary Grand Duke married Maria Teresa Mestre at the Cathédrale de Notre-Dame de Luxembourg. They have five children: • Prince Guillaume (born in 1981), the Hereditary Grand Duke, • Prince Félix (born in 1984), • Prince Louis (born in 1986), • Princess Alexandra (born in 1991) • Prince Sébastien (born in 1992). He became Head of State of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg on 7 October 2000. Preparing his role as future Head of State Prince Henri completed his secondary education in Luxembourg and France, where he passed his baccalaureate in 1974. He trained at the Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst in Great Britain and obtained the rank of officer in 1975. Prince Henri then enrolled at the Institut des hautes études internationales (Graduate Institute of International Studies) in Geneva, Switzerland, where he graduated with a Licence ès Sciences Politiques in 1980. Prince Henri met his future wife Maria Teresa Mestre during their university studies. Service Presse et Communication 1/7 In 1989, he was appointed Honorary Major of the Parachute Regiment in the United Kingdom. He also travelled extensively overseas to further his knowledge and education, particularly to the United States and Japan. As Hereditary Grand Duke, Prince Henri was an ex officio member of the Council of State from 1980 until 1998, which gave him insight into the legislative and institutional procedures and workings of the country. -

Friend Or a Sweetheart

- Tfffa StTNTTAY- - OEEGDNIAS, POHTLAlTDr MARCH 12, 1905. n ERL.XN", Feb. 23. (Special Correspond ence o The Sunday Oregonian.) It Is going: to cost Germany over 5500- .- 000 to get her future Emperor marriedf but In return for their money the folk of the Sutherland will have a show of pomp and ceremony such as seldom has been seen In modern Europe. In the preparation for his eldest son's wedding: to the Duchess Cecllie of Mecklenburg-Schwcri- n, which is now set for Monday. May 22, the Kaiser is giving: full rein to his love of imperial splendor and display. On. the marriage ceremony itself, which will take place In the magnificent new cathedral in Berlin, in the presence of an exalted company whose like has never gathered under one roof, $59,000 will be spent. The presents which will be given to the young- couple by municipalities and public corporations will amount to a total of at least J250.000, while a similar sum is being spent on the bride's trousseau. On her wedding day the Duchess Cecllie of Mccklenburg-Schwerl- n will be 39, all but .four months, while her young husband will have at- tained the age of 23 years and 2 weeks, to be exact. No part of the elaborate ceremonial la connection with her wedding will be more Impressive than the Duchess Cecllie's Journey from her home in Schwerln to Berlin, which will take place a few days before her marriage. From the palace of her brother, the Grand Duke of n, with whom she has lived CV 7WE S5Sy jyz&S'ZSAC. -

The Monarchs of England 1066-1715

The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King William I the Conqueror (1066-1087)— m. Matilda of Flanders (Illegitimate) (Crown won in Battle) King William II (Rufus) (1087-1100) King Henry I (1100-35) – m. Adela—m. Stephen of Blois Matilda of Scotland and Chartres (Murdered) The Empress Matilda –m. King Stephen (1135-54) –m. William d. 1120 Geoffrey (Plantagenet) Matilda of Boulogne Count of Anjou (Usurper) The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 The Empress Matilda – King Stephen (1135- m. Geoffrey 54) –m. Matilda of (Plantagenet) Count of Boulogne Anjou (Usurper) King Henry II (1154- 1189) –m. Eleanor of Eustace d. 1153 Aquitaine King Richard I the Lion King John (Lackland) heart (1189-1199) –m. Henry the young King Geoffrey d. 1186 (1199-1216) –m. Berengaria of Navarre d. 1183 Isabelle of Angouleme (Died in Battle) The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King John (Lackland) (1199- 1216) –m. Isabelle of Angouleme King Henry III (1216-1272) –m. Eleanor of Provence King Edward I Edmund, Earl of (1272-1307) –m. Leicester –m. Eleanor of Castile Blanche of Artois The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King Edward I Edmund, Earl of (1272-1307) –m. Leicester –m. Eleanor of Castile Blanche of Artois King Edward II Joan of Acre –m. (1307-27) –m. Thomas, Earl of Gilbert de Clare Isabella of France Lancaster (Murdered) Margaret de Clare – King Edward III m. Piers Gaveston (1327-77) –m. (Murdered) Philippa of Hainalt The Monarchs of England 1066-1715 King Edward III (1327-77) –m. Philippa of Hainalt John of Gaunt, Duke Lionel, Duke of Edward the Black of Lancaster d. -

Human Rights Certificate Electives

Human Rights Related Courses A course can count towards the human rights certificate if it contains a preponderance of readings or other materials of inquiry that reference human and civil rights history, concepts, theory, practice, discourse, advocacy or a combination of these elements. A course may have a thematic focus on human rights, including in areas of civil rights and social justice; it may have a regional focus, examining rights in a specific location; or a disciplinary focus, as in how a specific type of study, like biology or literature, approaches a rights question. Prior to registration each semester, the DHRC@FHI will prepare a list of pre-approved courses in consultation with the faculty advisory board. AAAS 207.01 African Americans Since 1865 INSTRUCTOR: Raymond Gavins Post-slavery black life and thought, as well as race relations and social change, during Reconstruction, Jim Crow, the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, and contemporary times; ethical concepts and issues on human justice in the course of struggles for democracy, tolerance, and equality. AAAS 209.01 Afro-Brazilian Culture and History INSTRUCTOR: Montie Pitts Slavery and the post-emancipation trajectory of Afro-Brazilians in a racist society that officially proclaims itself a "racial democracy." Comparisons drawn with the Afro- American experience elsewhere in Latin America and the United States. AAAS 213.01 Global Brazil INSTRUCTOR: John French Analysis of Brazilian history and culture from 1500 to the present in transnational context, with an emphasis on themes like slavery and race, regional cleavages, authoritarian rule, social inequality, and innovative attempts to expand democracy. -

League of the Public Weal, 1465

League of the Public Weal, 1465 It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake, nor to succeed in order to persevere. —Charles the Bold Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS 2018! My name is Josh Zucker, and I am excited to be your director for the League of the Public Weal. I am currently a junior studying Systems Engineering and Economics. I have always been interested in history (specifically ancient and medieval history) and politics, so Model UN has been a perfect fit for me. Throughout high school and college, I’ve developed a passion for exciting Model UN weekends, and I can’t wait to share one with you! Louis XI, known as the Universal Spider for his vast reach and ability to weave himself into all affairs, is one of my favorite historical figures. His continual conflicts with Charles the Bold of Burgundy and the rest of France’s nobles are some of the most interesting political struggles of the medieval world. Louis XI, through his tireless work, not only greatly transformed the monarchy but also greatly strengthened France as a kingdom and set it on its way to becoming the united nation we know today. This committee will transport you to France as it reinvents itself after the Hundred Years War. Louis XI, the current king of France, is doing everything in his power to reform and reinvigorate the French monarchy. Many view his reign as tyranny. You, the nobles of France, strive to keep the monarchy weak. For that purpose, you have formed the League of the Public Weal. -

His Royal Highness the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

A COMMEMORATION OF HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE PHILIP, DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A COMMEMORATION OF HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE PHILIP, DUKE OF EDINBURGH We meet this day to remember before God His Royal Highness PHILIP, Duke of Edinburgh, to renew our trust and confidence in Christ, and, at a time when many have been bereaved, to pray that we all may be one in him, through whom we offer our prayers and praises to the Father. THE SENTENCES Jesus said, I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die. John 11:25, 26 We brought nothing into the world, and we cannot take anything out of the world. The LORD gave, and the LORD has taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD. 1 Timothy 6:7, Job 1:21 The eternal God is your dwelling place, and underneath are the everlasting arms. Deuteronomy 33:27 I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. Romans 8:38, 39 A COMMEMORATION OF HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE PHILIP, DUKE OF EDINBURGH THE INTROIT God be in my head, And in my understanding; God be in mine eyes, And in my looking; God be in my mouth, And in my speaking; God be in my heart, And in my thinking; God be at mine end, And at my departing. -

155 Coping with a Title

Coping with a title: the indexer and the British aristocracy David Lee The names of peers occur frequently in books, and of course in their indexes. The English peerage system is not straightforward; it is so easy to make errors in the treatment of the names of peers and knights and their ladies, causing confusion to readers, that an article warning of pitfalls seems worthwhile.1 It is sometimes necessary to do research on peers and their titles, and this article gives the necessary clues. Whilst the article is in part general, the particular problems of indexers are covered, such as the form of name, and the order of entries. Introduction Beaumont. The 16th Duke's barony of Herries, however, First, a couple of warnings. This article is concerned was able to pass to a woman, and his eldest daughter, with the English peerage, and any statement cannot Lady Anne Fitzalan-Howard, duly became Baroness automatically be applied to practice in other countries. I Herries in her own right. At times a peerage may be in am no great expert on Scots and Irish peerage, so they abeyance, the final heir not being clear, and there are will crop up here rarely. Nor is this article concerned wonderful cases where claims to ancient peerages have with the special problems of indexing royalty. Further, been proved centuries later. It still happens, as in the case the article expresses one man's views and there can be of Jean Cherry Drummond, Baroness Strange, whose room for differences in interpretation and treatment, peerage came out of abeyance only in 1986, for much which I shall try to indicate as we go on. -

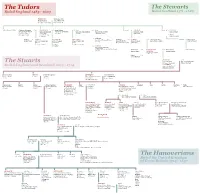

The Stuarts the Tudors the Hanoverians

The Tudors The Stewarts Ruled England 1485 - 1603 Ruled Scotland 1371 - 1603 HENRY VII = Elizabeth of York King of England dau. of Edward IV, (b. 1457, r. 1485-1509) King of England Arthur Prince of Wales Catherine of Aragon (1) = HENRY VIII = (2) Anne Boleyn = (3) Jane = (4) Anne Margaret = JAMES IV Mary = (1) LOUIS XII dau of FERDINAND V. King of England and dau of Earl of Wiltshire dau of Sir John Seymour dau of Duke of Cleves King of Scotland King of France first King of Spain (from 1541) (ex. 1536) (d. 1537) (div 1540 d.1557) (1488-1513) (div 1533. d. 1536.) Ireland (b. 1491, = (2) Charles r. 1509-47) Duke of Suffolk = (5) Catherine (1) (2) Phillip II = MARY I ELIZABETH I EDWARD VI dau of Lord Edmund Howard Madeline = JAMES V = Mary of Lorraine Frances = Henry Grey King of Spain Queen of England and Queen of England King of England and (ex 1542) dau of FRANCIS I. King of Scotland dau of Duke of Guise Duke of Suffolk Ireland and Ireland Ireland King of France (d. 1537) (1513-1542) (b. 1516, r. 1553-8) (b. 1533, r. (b. 1537, r. 1547-53) 1558-1603) = (6) Catherine dau of Sir Thomas Parr (HENRY VIII was her third husband) FRANCIS II (1) = MARY QUEEN = (2) Henry Stuart Lady Jane Grey (d. 1548) King of France OF SCOTS Lord of Darnley (1542-1567. ex 1587) James (3) = Earl of Bothwell JAMES VI = Anne The Stuarts King of Scotland dau. of FREDERICK II, (b. 1566, r. 1567-1625) King of Denmark and JAMES I, Ruled England and Scotland 1603 - 1714 King of England and Ireland (r.