155 Coping with a Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The London Gazette, 25 March, 1930. 1895

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25 MARCH, 1930. 1895 panion of Our Distinguished Service Order, on Sir Jeremiah Colman, Baronet, Alfred Heath- whom we have conferred the Decoration of the cote Copeman, Herbert Thomas Crosby, John Military Cross, Albert Charles Gladstone, Francis Greenwood, Esquires, Lancelot Wilkin- Alexander Shaw (commonly called the Honour- son Dent, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excel- able Alexander Shaw), Esquires, Sir John lent Order of the British Empire, Edwin Gordon Nairne, Baronet, Charles Joeelyn Hanson Freshfield, Esquire, Sir James Hambro, Esquire, Sir Josiah Charles Stamp, Fortescue Flannery, Baronet, Charles John Knight Grand Cross of Our Most Excellent Ritchie, Esquire, Officer of Our Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Sir Ernest Mus- Order of the British Empire; OUR right trusty grave Harvey, Knight Commander of Our and well-beloved Charles, Lord Ritchie of Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, Dundee; OUR trusty and well-beloved Sir Sir Basil Phillott Blackett, Knight Commander Alfred James Reynolds, Knight, Percy Her- of Our Most Honourable Order of the Bath, bert Pound, George William Henderson, Gwyn Knight Commander of Our Most Exalted Order Vaughan Morgan, Esquires, Frank Henry of the Star of India, Sir Andrew Rae Duncan, Cook, Esquire, Companion of Our Most Knight, Edward Robert Peacock, James Lionel Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, Ridpath, Esquires, Sir Homewood Crawford, Frederick Henry Keeling Durlacher, Esquire, Knight, Commander of Our Royal Victorian Colonel Sir Charles Elton Longmore, Knight Order; Sir William Jameson 'Soulsby, Knight Commander of Our Most Honourable Order of Commander of Our Royal Victorian Order, the Bath, Colonel Charles St. -

97 Winter 2017–18 3 Liberal History News Winter 2017–18

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 97 / Winter 2017–18 / £7.50 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y The Forbidden Ground Tony Little Gladstone and the Contagious Diseases Acts J. Graham Jones Lord Geraint of Ponterwyd Biography of Geraint Howells Susanne Stoddart Domesticity and the New Liberalism in the Edwardian press Douglas Oliver Liberals in local government 1967–2017 Meeting report Alistair J. Reid; Tudor Jones Liberalism Reviews of books by Michael Freeden amd Edward Fawcett Liberal Democrat History Group “David Laws has written what deserves to become the definitive account of the 2010–15 coalition government. It is also a cracking good read: fast-paced, insightful and a must for all those interested in British politics.” PADDY ASHDOWN COALITION DIARIES 2012–2015 BY DAVID LAWS Frank, acerbic, sometimes shocking and often funny, Coalition Diaries chronicles the historic Liberal Democrat–Conservative coalition government through the eyes of someone at the heart of the action. It offers extraordinary pen portraits of all the personalities involved, and candid insider insight into one of the most fascinating periods of recent British political history. 560pp hardback, £25 To buy Coalition Diaries from our website at the special price of £20, please enter promo code “JLH2” www.bitebackpublishing.com Journal of Liberal History advert.indd 1 16/11/2017 12:31 Journal of Liberal History Issue 97: Winter 2017–18 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Obituary of Bill Pitt; events at Gladstone’s Library Deputy Editors: Mia Hadfield-Spoor, Tom Kiehl Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Archive Sources Editor: Dr J. -

Crowns and Mantles: the Ranks and Titles of Cormyr Bands

Crowns and Mantles The Ranks and Titles of Cormyr By Brian Cortijo Illustrations by Hector Ortiz and Claudio Pozas “I give my loyal service unfailingly to the with ranks or titles, or with positions of authority and command, especially as they rise to national impor- Mage Royal of Cormyr, in full obedience tance and take on threats to the kingdom. of speech and action, that peace and order Descriptions of the most important of these titles shall prevail in the Forest Kingdom, that appear below. Each bears with it duties, privileges, magic of mine and others be used and not and adventuring opportunities that otherwise might be closed off to adventurers with less interest in serv- misused. I do this in trust that the Mage ing Cormyr in an official capacity. Because few heroes Royal shall unswervingly serve the throne might wish to be weighed down by such responsibility, of Cormyr, and if the Mage Royal should the option exists to delay an appointment or investiture of nobility until after one’s retirement. fall, or fail the Crown and Throne, my obedience shall be to the sovereign directly. REGISTRATION AS Whenever there is doubt and dispute, I ITLE shall act to preserve Cormyr. Sunrise and T moonfall, as long as my breath takes and Even in the absence of a rank of honor or a title of nobility, most adventurers are already registered, in my eyes see, I serve Cormyr. I pledge my one form or another, with the Crown of Cormyr if life that the realm endure.” they wish to operate within the kingdom. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Introduction to the Abercorn Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION ABERCORN PAPERS November 2007 Abercorn Papers (D623) Table of Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................2 Family history................................................................................................................3 Title deeds and leases..................................................................................................5 Irish estate papers ........................................................................................................8 Irish estate and related correspondence.....................................................................11 Scottish papers (other than title deeds) ......................................................................14 English estate papers (other than title deeds).............................................................17 Miscellaneous, mainly seventeenth-century, family papers ........................................19 Correspondence and papers of the 6th Earl of Abercorn............................................20 Correspondence and papers of the Hon. Charles Hamilton........................................21 Papers and correspondence of Capt. the Hon. John Hamilton, R.N., his widow and their son, John James, the future 1st Marquess of Abercorn....................22 Political correspondence of the 1st Marquess of Abercorn.........................................23 Political and personal correspondence of the 1st Duke of Abercorn...........................26 -

Welsh Disestablishment: 'A Blessing in Disguise'

Welsh disestablishment: ‘A blessing in disguise’. David W. Jones The history of the protracted campaign to achieve Welsh disestablishment was to be characterised by a litany of broken pledges and frustrated attempts. It was also an exemplar of the ‘democratic deficit’ which has haunted Welsh politics. As Sir Henry Lewis1 declared in 1914: ‘The demand for disestablishment is a symptom of the times. It is the democracy that asks for it, not the Nonconformists. The demand is national, not denominational’.2 The Welsh Church Act in 1914 represented the outcome of the final, desperate scramble to cross the legislative line, oozing political compromise and equivocation in its wake. Even then, it would not have taken place without the fortuitous occurrence of constitutional change created by the Parliament Act 1911. This removed the obstacle of veto by the House of Lords, but still allowed for statutory delay. Lord Rosebery, the prime minister, had warned a Liberal meeting in Cardiff in 1895 that the Welsh demand for disestablishment faced a harsh democratic reality, in that: ‘it is hard for the representatives of the other 37 millions of population which are comprised in the United Kingdom to give first and the foremost place to a measure which affects only a million and a half’.3 But in case his audience were insufficiently disheartened by his homily, he added that there was: ‘another and more permanent barrier which opposes itself to your wishes in respect to Welsh Disestablishment’, being the intransigence of the House of Lords.4 The legislative delay which the Lords could invoke meant that the Welsh Church Bill was introduced to parliament on 23 April 1912, but it was not to be enacted until 18 September 1914. -

Dame Lucy Neville-Rolfe DBE, CMG, FCIS Biography ______

Dame Lucy Neville-Rolfe DBE, CMG, FCIS Biography ___________________________________________________________________________ Non-Executive President of Eurocommerce since July 2012, Lucy Neville-Rolfe began her retail career in 1997 when she joined Tesco as Group Director of Corporate Affairs. She went on to also become Company Secretary (2004-2006) before being appointed to the Tesco plc Board where she was Executive Director (Corporate and Legal Affairs) from 2006 to January 2013. Lucy is a life peer and became a member of the UK House of Lords on 29 October 2013. Before Tesco she worked in a number of UK Government departments, starting with the then Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, where she was private secretary to the Minister. She was a member of the UK Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1992 – 1994 where her responsibilities included home and legal affairs. She later became Director of the Deregulation Unit, first in the DTI and then the Cabinet Office from 1995 - 1997. In 2013 Lady Neville-Rolfe was elected to the Supervisory Board of METRO AG. She is also a member of the UK India Business Advisory Council. She is a Non-Executive Director of ITV plc, and of 2 Sisters Food Group, a member of the PWC Advisory Board and a Governor of the London Business School. She is a former Vice– President of Eurocommerce and former Deputy Chairman of the British Retail Consortium In 2012 she was made a DBE (Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in the Queen’s Birthday Honours in recognition of her services to industry and the voluntary sector. -

Contents Theresa May - the Prime Minister

Contents Theresa May - The Prime Minister .......................................................................................................... 5 Nancy Astor - The first female Member of Parliament to take her seat ................................................ 6 Anne Jenkin - Co-founder Women 2 Win ............................................................................................... 7 Margaret Thatcher – Britain’s first woman Prime Minister .................................................................... 8 Penny Mordaunt – First woman Minister of State for the Armed Forces at the Ministry of Defence ... 9 Lucy Baldwin - Midwifery and safer birth campaigner ......................................................................... 10 Hazel Byford – Conservative Women’s Organisation Chairman 1990 - 1993....................................... 11 Emmeline Pankhurst – Leader of the British Suffragette Movement .................................................. 12 Andrea Leadsom – Leader of House of Commons ................................................................................ 13 Florence Horsbrugh - First woman to move the Address in reply to the King's Speech ...................... 14 Helen Whately – Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party ............................................................. 15 Gillian Shephard – Chairman of the Association of Conservative Peers ............................................... 16 Dorothy Brant – Suffragette who brought women into Conservative Associations ........................... -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

House of Lords Library Note: the Life Peerages Act 1958

The Life Peerages Act 1958 This year sees the 50th anniversary of the passing of the Life Peerages Act 1958 on 30 April. The Act for the first time enabled life peerages, with a seat and vote in the House of Lords, to be granted for other than judicial purposes, and to both men and women. This Library Note describes the historical background to the Act and looks at its passage through both Houses of Parliament. It also considers the discussions in relation to the inclusion of women life peers in the House of Lords. Glenn Dymond 21st April 2008 LLN 2008/011 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Life peerages – an historical overview .......................................................................... 2 2.1 Hereditary nature of peerage................................................................................... 2 2.2 Women not summoned to Parliament ..................................................................... 2 2.3 Early life peerages.................................................................................................. -

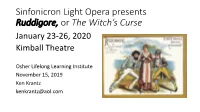

Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with Date and Length of Original London Run • Thespis 1871 (63)

Sinfonicron Light Opera presents Ruddigore, or The Witch’s Curse January 23-26, 2020 Kimball Theatre Osher Lifelong Learning Institute November 15, 2019 Ken Krantz [email protected] Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia + Delta Omicron = Sinfonicron G&S Works, with date and length of original London run • Thespis 1871 (63) • Trial by Jury 1875 (131) • The Sorcerer 1877 (178) • HMS Pinafore 1878 (571) • The Pirates of Penzance 1879 (363) • Patience 1881 (578) • Iolanthe 1882 (398) G&S Works, Continued • Princess Ida 1884 (246) • The Mikado 1885 (672) • Ruddigore 1887 (288) • The Yeomen of the Guard 1888 (423) • The Gondoliers 1889 (554) • Utopia, Limited 1893 (245) • The Grand Duke 1896 (123) Elements of Gilbert’s stagecraft • Topsy-Turvydom (a/k/a Gilbertian logic) • Firm directorial control • The typical issue: Who will marry the soprano? • The typical competition: tenor vs. patter baritone • The Lozenge Plot • Literal lozenge: Used in The Sorcerer and never again • Virtual Lozenge: Used almost constantly Ruddigore: A “problem” opera • The horror show plot • The original spelling of the title: “Ruddygore” • Whatever opera followed The Mikado was likely to suffer by comparison Ruddigore Time: Early 19th Century Place: Cornwall, England Act 1: The village of Rederring Act 2: The picture gallery of Ruddigore Castle, one week later Ruddigore Dramatis Personae Mortals: •Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd, Baronet, disguised as Robin Oakapple (Patter Baritone) •Richard Dauntless, his foster brother, a sailor (Tenor) •Sir Despard Murgatroyd, Sir Ruthven’s younger brother -

Judicial Titles and Dress in the Supreme Court and Below

Judicial titles and dress in the Supreme Court and below by Graham Zellick INTRODUCTION the High Court, normally Lords Justices on their appointment, surrender their title of Lord Justice and revert to their name: This article describes and comments on the titles accorded Sir James Munby, Sir Terence Etherton and Sir Brian Leveson to Supreme Court justices and the Court’s policy on judicial are the three current Heads of Division who presumably feel and barristers’ costume, criticises the absence of any public in no need of a more exalted title to maintain their authority discussion of these matters and considers some issues in and leadership. The same has often been true in the past of relation to judicial titles and dress generally. It also comments the Master of the Rolls. on the recent peerage conferred on the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales. Had no change been made, it would have been only a matter of time before all but the Supreme Court judges from Scotland TITLES FOR SUPREME COURT JUDGES would have been knights and dames without any other title. That is, of course, on the assumption that any person appointed It is odd that at no time between the government’s proposal direct to the Supreme Court from the Bar would be knighted to replace the House of Lords as a judicial body and the or appointed a Dame as is the custom with High Court judges. creation of the Supreme Court by the Constitutional Reform Mr Jonathan Sumption QC was not, however, knighted on his Act 2005 was there any consideration or public discussion of appointment to the Supreme Court, presumably because the the title, if any, to be accorded to the justices of the new Court.