Esther Not Judith: Why One Made It and the Other Didn’T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs: Videos: Purim Song – The Maccabeats Audio Reading: Book of Esther Feast of Purim Purim is an annual celebration of the defeat of an Iranian mad man’s plan to exterminate the Jewish people. Purim is celebrated annually during the month of Adar (the second month of Adar) on the 14th day. In years where there are two months of Adar, Purim is celebrated in the second month because it always needs to fall 30 days before Passover. It is called Purim because the word means “lots” – referencing when Haman threw lots to decide which day he would slay the Jews. The fourteenth was chosen for this celebration because it is the day that the Jews battled for their lives and won. The fifteenth is celebrated as Purim also because the book of Esther says that in Shushan (a walled city), deliverance from the scheduled massacre was not completed until the next day. So the fifteenth is referred to as Shushan Purim. Traditions for the Feast of Purim: It is customary to read the book of Esther – called the Megillah Esther – or the scroll of Esther. It means the revelation of that which is hidden While reading it is tradition to boo, hiss, stamp feet and rattle noise makers whenever Haman’s name is mentioned for the purpose of “blotting out the name of Haman”. When the names of Mordechai or Esther are spoken, hoots and hollers, cheering, applause, etc., are given as they are the heroes of the story. -

GOD in the ORDINARY Text: Esther 6 Topic: God's Timing

LIFE GROUP GUIDE Title: GOD IN THE ORDINARY Text: Esther 6 Topic: God's timing MAIN POINT Those who oppose the purposes of God will face God’s judgment. DELIVER – Use this space to take notes during the sermon. Additional commentary is also available to rightly understand and teach God’s Word. Sermon Notes: 1. God doesn't forget His children (v. 1-5) 2. Left to ourselves, we will work for our own glory (v. 6-9) 3. Our pursuit determines out future (v. 10-14) DISCIPLE – Use these questions to engage people in discussion on a personal level. Ask everyone to open their sermon notes and Bibles. ➢ Read (or have a volunteer read) Esther 6:1-5 ➢ Review the sermon point: “God doesn’t forget His children” Share from your notes and ask group members for insights. 1. What was Haman on his way to do when he entered the king’s court? 2. How does God show that he is providentially working to protect Mordecai? 3. What would have happened if Mordecai had been honored for his efforts to protect the king when he did it five years ago? 4. What do these verses contribute to the idea that God providentially cares for us like he did with Mordecai: Phillipians 4:19; Jude 24; Hebrews 13:6; 2 Timothy 4:18? Haman was on his way to convince the king that it would be a good idea to kill Mordecai because of his lack of reverence (and because he is a Jew). However, God was working through the timing of his arrival. -

Learning to Trust God's Unseen Hand

Learning to Trust God’s Unseen Hand A Study of Esther Esther 9:119 Lesson #11: In times of defense, remember mercy. Introduction: Consider the interesting wording of the last stanza of the StarSpangled Banner: Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand Between their loved home and the war’s desolation! Blest with victory and peace, may the heav’n rescued land Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation. Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just, And this be our motto: “In God is our trust.” And the starspangled banner in triumph shall wave O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave! A question that is raised here is this: by what do we gain or lose by invoking the name of God when it comes the fighting of a battle? Is it appropriate to invoke the name of God when going to war? While the answers to these questions are not easy, they are nonetheless worthy of inquiry. Too easily have we just associated God’s covenant relationship with the Jews as having the same legitimacy for America. In addressing this issue, we find that while God’s relationship with Israel is unique, there are moral focal points that we can be applied to any culture at any time, including how we are to defend ourselves from those who will attack us because of our faith. Verses 110 The author builds a chiastic structure into his presentation of the events pictured in 9:1–19. -

![Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4834/prints-and-johan-wittert-van-der-aa-in-the-rijksmuseum-in-amsterdam-7-drawings-inv-254834.webp)

Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv

Esther before Ahasuerus ca. 1640–45 oil on panel Jan Adriaensz van Staveren 86.7 x 75.2 cm (Leiden 1613/14 – 1669 Leiden) signed in light paint along angel’s shield on armrest of king’s throne: “JOHANNES STAVEREN 1(6?)(??)” JvS-100 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Esther before Ahasuerus Page 2 of 9 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Esther before Ahasuerus” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/esther-before-ahasuerus/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Esther before Ahasuerus Page 3 of 9 During the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, the beautiful Jewish orphan Comparative Figures Esther, heroine of the Old Testament Book of Esther, won the heart of the austere Persian king Ahasuerus and became his wife (Esther 2:17). Esther had been raised by her cousin Mordecai, who made Esther swear that she would keep her Jewish identity a secret from her husband. However, when Ahasuerus appointed as his minister the anti-Semite Haman, who issued a decree to kill all Jews, Mordecai begged Esther to reveal her Jewish heritage to Ahasuerus and plead for the lives of her people. Esther agreed, saying to Mordecai: “I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. -

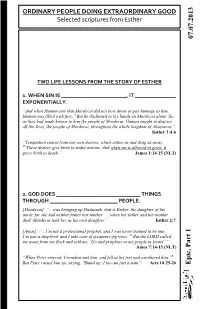

07.07.13 Final

ORDINARY PEOPLE DOING EXTRAORDINARY GOOD Selected scriptures from Esther 07.07.2013 TWO LIFE LESSONS FROM THE STORY OF ESTHER 1. WHEN SIN IS ________________________, IT _______________ EXPONENTIALLY. “And when Haman saw that Mordecai did not bow down or pay homage to him, Haman was filled with fury. 6 But he disdained to lay hands on Mordecai alone. So, as they had made known to him the people of Mordecai, Haman sought to destroy all the Jews, the people of Mordecai, throughout the whole kingdom of Ahasuerus.” Esther 3:4-6 “Temptation comes from our own desires, which entice us and drag us away. 15 These desires give birth to sinful actions. And when sin is allowed to grow, it gives birth to death.” James 1:14-15 (NLT) 2. GOD DOES _______________________________ THINGS THROUGH _________________________ PEOPLE. [Mordecai]: “…was bringing up Hadassah, that is Esther, the daughter of his uncle, for she had neither father nor mother. ….when her father and her mother died, Mordecai took her as his own daughter.” Esther 2:7 [Amos]: “…I’m not a professional prophet, and I was never trained to be one. I’m just a shepherd, and I take care of sycamore-fig trees. 15 But the LORD called me away from my flock and told me, ‘Go and prophesy to my people in Israel.’” Amos 7:14-15 (NLT) “When Peter entered, Cornelius met him, and fell at his feet and worshiped him. 26 But Peter raised him up, saying, "Stand up; I too am just a man.” Acts1 10:25-26Part Epic, MAKE IT PERSONAL: 1. -

A REWRITTEN BIBLICAL BOOK the So-Called Lucianic

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN THE ‘LUCIANIC’ TEXT OF THE CANONICAL AND APOCRYPHAL SECTIONS OF ESTHER: A REWRITTEN BIBLICAL BOOK The so-called Lucianic (L) text of Esther is contained in manuscripts 19 (Brooke-McLean: b’), 93 (e2), 108 (b), 319 (y), and part of 392 (see Hanhart, Esther, 15–16). In other biblical books the Lucianic text is joined by manuscripts 82, 127, 129. In Esther this group is traditionally called ‘Lucianic’ because in most other books it represents a ‘Lucianic’ text, even though the ‘Lucianic’ text of Esther and that of the other books have little in common in either vocabulary or translation technique.1 The same terminology is used here (the L text). Some scholars call this text A, as distinct from B which designates the LXX.2 Brooke-McLean3 and Hanhart, Esther print the LXX and L separately, just as Rahlfs, Septuaginta (1935) provided separate texts of A and B in Judges. Despite the separation between L and the LXX in these editions, the unique character of L in Esther was not sufficiently noted, possibly because Rahlfs, Septuaginta does not include any of its readings. Also HR 1 Scholars attempted in vain to detect the characteristic features of LXXLuc in Esther as well. For example, the Lucianic text is known for substituting words of the LXX with synonymous words, and a similar technique has been detected in Esther by Cook, “A Text,” 369–370. However, this criterion does not provide sufficient proof for labeling the L text of Esther ‘Lucianic,’ since the use of synonymous Greek words can be expected to occur in any two Greek translations of the same Hebrew text. -

The Rest of the Chapters of the Book of Esther 10 PART of the TENTH CHAPTER AFTER the GREEK 4 Then Mardocheus Said, God Hath Done These Things

Esther (Greek) 10:4 1 Esther (Greek) 10:13 The Rest of the Chapters of the Book of Esther 10 PART OF THE TENTH CHAPTER AFTER THE GREEK 4 Then Mardocheus said, God hath done these things. 5 For I remember a dream which I saw concerning these matters, and nothing thereof hath failed. 6 A little fountain became a river, and there was light, and the sun, and much water: this river is Esther, whom the king married, and made queen: 7 And the two dragons are I and Aman. 8 And the nations were those that were assembled to destroy the name of the Jews: 9 And my nation is this Israel, which cried to God, and were saved: for the Lord hath saved his people, and the Lord hath delivered us from all those evils, and God hath wrought signs and great wonders, which have not been done among the Gentiles. 10 Therefore hath he made two lots, one for the people of God, and another for all the Gentiles. 11 And these two lots came at the hour, and time, and day of judgment, before God among all nations. 12 So God remembered his people, and justified his inheritance. 13 Therefore those days shall be unto them in the month Adar, the fourteenth and fifteenth day of the same month, with an assembly, and joy, and with gladness before God, according to the generations for ever among his people. Esther (Greek) 11:1 2 Esther (Greek) 11:11 11 1 In the fourth year of the reign of Ptolemeus and Cleopatra, Dositheus, who said he was a priest and Levite, and Ptolemeus his son, brought this epistle of Phurim, which they said was the same, and that Lysimachus the son of Ptolemeus, that was in Jerusalem, had interpreted it. -

Bible Grade 3 Esther Curriculum Review Sheets Teacher

Name Date Esther Look at the underlined word to determine if the statement is true or True–False false. If the statement is true, write true in the blank. If the statement is false, write false in the blank. true 1. Haman wanted to kill Mordecai because Mordecai refused to bow down to him. false 2. Haman was rewarded for saving the king’s life. (Mordecai) true 3. Mordecai sent a message to Esther that she should ask the king to save the lives of the Jews. false 4. Mordecai, Esther, and their friends fasted ten days and nights. (three) true 5. Esther risked her life by going before the king when he had not sent for her. false 6. Esther invited the king and Haman to three banquets. (two) true 7. Haman had to lead Mordecai through the city and proclaim that he was being honored by the king. true 8. Although the name of God is not mentioned in the book of Esther, the book tells of God’s protection for His people. Discuss: Explain why the false answers are incorrect statements. Short Answer Read each question carefully, and write your answer in the blank. 1. How did Haman trick King Ahasuerus into sending out a decree to kill all the Jews? He pretended to be concerned about the entire kingdom and told the king that the kingdom would be better off without the Jews. over Copyright © mmxviii Pensacola Christian College • Not to be reproduced. Esther • Lesson 125 231 Esther • page 2 2. What should King Ahasuerus have done before allowing the decree to be sent out? Answers vary. -

Esther 10:1-3 Dr

Book Study on Esther Mortdecai’s Fame Esther 10:1-3 Dr. Bill Gilmore Oakleaf Baptist Church, Orange Park, Florida Wednesday, September 30, 2020 PM Introduction • Review books of the Bible: Genesis – Esther • Last time we ended with Esther and Mordecai sending the decree to celebrate Purim. Every year on the 14-15 of Adar. Let’s pick up here in chapter 10 and verse 1 Lets look a little deeper into these verses: Est 10:1 And the king Ahasuerus laid a tribute upon the land, and upon the isles of the sea. • This passage being an appendix to the history, and improperly separated from the preceding chapter, it might be that the occasion of levying this new impost arose out of the commotions raised by Haman‘s conspiracy. Neither the nature nor the amount of the tax has been recorded; only it was not a local tribute, but one exacted from all parts of his vast empire.1 • Upon the isles of the sea - Cyprus, Aradus, the island of Tyre, Platea, etc., remained in the hands of the Persians after the victories of the Greeks, and may be the “isles” here intended.2 • The isles of the sea - Probably the isles of the Aegean sea, which were conquered by Darius Hystaspes. Calmet supposes that this Hystaspes is the Ahasuerus of Esther.3 • The disastrous expedition to Greece must have taxed the resources of the empire to the utmost, and fresh tribute would therefore be requisite to fill the exhausted coffers. Besides this, a harassing war was still going on, even ten years after the battle of Salamis, on the coast of Asia Minor, and this would require fresh supplies.4 Est 10:2 And all the acts of his power and of his might, and the declaration of the greatness of Mordecai, whereunto the king advanced him, are they not written in the book of the chronicles of the kings of Media and Persia? • The Targum characteristically adds that when Ahasuerus knew who the people and family of Esther were, he declared them free.5 • The same word as that translated authority in Esther 9:29.4 • The declaration of the greatness of Mordecai. -

Esther 1 Reading Guide

Esther: The Faithfulness of an Unseen God Some stories are so compelling and powerful that they deserve to be told over and over again. The book of Esther represents one such story. It was written as a means to help shape the corporate identity of the Jewish people several thousand years ago, written to remind the people of God living in a broken and hostile world that their God would be faithful to deliver them. But as we come to Esther all these centuries later, we recognize that it is a challenging book for us to engage and apply in some ways. It wasn’t written to serve primarily as a moral how-to book. It doesn’t possess the same sense of gospel-shaped exhortation that we might find in a New Testament epistle, nor does it offer the multi-faceted view of the Kingdom of God as do the Gospels. It is not Wisdom Literature, nor is it a prophetic book filled with apocalyptic images and warnings for God’s people. It does not even offer the same exemplary lives to emulate as did Ruth’s narrative. It’s devoid of the name of God, devoid of any explicit mention of God, and it shares a murky and messy picture of what it means to live as an exile in a world that can be hostile toward God and his people. So one of the questions we have to wrestle with as we read through it is, how am I to understand truth in this story and apply it to my life? It’s a story that was written, and then read, with the purpose of growing God’s peoples’ collective confidence in his faithful deliverance. -

Haman the Heartless Esther 3 Intro

Haman the Heartless 3) You begin to understand Haman’s Esther 3 hatred for the Jews Intro: • He was a descendant of those A) In chapter 1 we discussed …. who attacked a weary Israel after 1) The king and his corruption they fled from Egypt 2) Queen Vashti and her character • God delivered them into the hands 3) The world and its ungodly counsel of Israel B) In chapter 2 we continued with …. • Saul didn’t obey and utterly 1) The lonely problem of the king destroyed them 2) The procedure to find a queen • They now are facing the results of 3) The providence of God through it all this disobedience • We ended with King Ahasuerus’ 4) A neat thing to acknowledge is …. life being spared because of • Saul from the tribe of Benjamin, Mordecai failed to destroy the Amalekites C) In chapter 3 our narrative introduces • But Mordecai, also a Benjamite, another character, Haman took up the battle and defeated 1) Haman is an “ancient day” Hitler Haman • He is waiting 5) Everything about Haman is hateful 2) Haman is an Agagite (from empire • You can’t find a good quality in known as Agag) anything written about him • Agag was king of the Amalekites • Proverbs 6:16-19 “These six things • I Samuel 15:2 “Thus saith doth the Lord hate: yea, seven are the Lord of hosts, I remember that an abomination unto him: A proud which Amalek did to Israel, how he look, a lying tongue, and hands that laid wait for him in the way, when shed innocent blood, An heart that he came up from Egypt.” deviseth wicked imaginations, feet • I Samuel 15:8 “And he took Agag that be swift in running to mischief, the king of the Amalekites alive, A false witness that speaketh lies, and utterly destroyed all the people and he that soweth discord among with the edge of the sword.” brethren.” • Saul actually disobeyed His Lord in • You will notice each quality as you not destroying all the Amalekites read of Haman D) Let’s study and see several aspects C) His vanity (Vs. -

Early Jewish Writings

EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Press SBL T HE BIBLE AND WOMEN A n Encyclopaedia of Exegesis and Cultural History Edited by Christiana de Groot, Irmtraud Fischer, Mercedes Navarro Puerto, and Adriana Valerio Volume 3.1: Early Jewish Writings Press SBL EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2017 by SBL Press A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,S BL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schuller, Eileen M., 1946- editor. | Wacker, Marie-Theres, editor. Title: Early Jewish writings / edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, [2017] | Series: The Bible and women Number 3.1 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers:L CCN 2017019564 (print) | LCCN 2017020850 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142324 (ebook) | ISBN 9781628371833 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780884142331 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Old Testament—Feminist criticism. | Women in the Bible. | Women in rabbinical literature. Classification: LCC BS521.4 (ebook) | LCC BS521.4 .E27 2017 (print) | DDC 296.1082— dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019564 Press Printed on acid-free paper.