Rendlesham in Suffolk Has Identified a Major Central Place Complex of the Early–Middle Anglo-Saxon Periods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Services Operating Through Rushmere St Andrew

Bus Services operating through Rushmere St Andrew Route 4 Ipswich to Bixley Farm via Felixstowe Road & Broke Hall Operated by Ipswich Buses (Tel 0800 919390) Web: www.ipswichbuses.co.uk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime - approximately every half hour. Route: Ipswich Tower Ramparts - Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Felixstowe Road – Broke Hall –Bixley Farm (via Foxhall Road, Broadlands Way, District Centre & Bixley Drive). Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 01/11/15 Route and timetable changes 11/04/16 Timetable changes 04/09/16 Minor timetable change 18/02/18 Timetable changes, route no longer serves Ipswich Railway station or Martlesham Heath Route 63 Ipswich to Framlingham via Woodbridge Road, Kesgrave, Martlesham, Woodbridge, Wickham Market & Hacheston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk One school days journey each way. Route: Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Woodbridge Road - Kesgrave (Main Road) – Fentons Way (4 services only) – Cambridge Road / Edmonton Close (3 services only) Martlesham Tesco - Woodbridge – Melton Chapel – Ufford – Wickham Market – Hacheston – Framlingham (Thomas Mills) All services are wheelchair and buggy-accessible. Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 30/08/15 Timetable changes 03/01/16 Timetable changes 27/03/16 Timetable changes 02/07/17 Extended route, now school days only – otherwise remainder within 64 service. Route 64 Ipswich to Aldeburgh via Woodbridge Road, Woodbridge, Melton, Saxmundham & Leiston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime and early evening – typically every hour. -

Rendlesham Neighbourhood Plan

Rendlesham Neighbourhood Plan Rendlesham Parish Council 2014- 2027 APPENDICES (January 2015) Locality Parish Office 33 Corsham Street, Rendlesham Community Centre London N1 6DR Walnut Tree Avenue Rendlesham Opus House 0845 458 8336 Suffolk [email protected] IP12 2GG T: 01394 420207 www.locality.org.uk 01359 233663 E: [email protected] .uk All photos: ©H Heelis unless otherwise stated 2 List of Appendices Appendices: A— Village Asset Map (contained within the main Neighbourhood Plan document) B—Decision Notification Letter C— SASR Response from Natural England D—Evidence for Affordable Housing E—Policy Context F—Sport in Communities G—Listing of Assets of Community Value: Angel Theatre and Sports Centre H—Assessment of community & leisure space required in the District Centre I—Education J—Bentwaters Master Plan K—Bentwaters Airbase, former Local Plan inset map L—Suffolk Coastal Leisure Strategy M—Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty N—Summary of lost facilities/services O—Housing stock and neighbourhoods of Rendlesham P– Analysis of bus survey 3 4 Appendices 5 6 Appendix B 7 8 Appendix C 9 Appendix C 10 Appendix D Evidence for Affordable Housing Report – Full Council 3 March 2014 Consideration of Affordable Housing Scheme in Rendlesham BACKGROUND In September 2012 the Parish Council undertook a Housing Needs Survey as part of the Neighbourhood Plan process in order to identify whether there was any defined need in Rendlesham for ‘affordable’ housing for local people. The survey was undertaken by Suffolk ACRE who collated and analysed the results. Suffolk ACRE is an independent organisation and the enabling body for affordable housing schemes in Suffolk. -

Supporting Evidence Melton Parish

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE MELTON PARISH - ROAD TRANSPORT PROBLEMS THAT WILL BE EXACERBATED BY THE SIZEWELL C & FRISTON ENERGY SCHEMES V5 Introduction 1. This paper describes the background to the current heavy and growing traffic through Melton Parish. It explains that the major energy projects at Friston and Sizewell C (SZC) would hugely exacerbate the traffic volumes that cut through the middle of Melton village, causing delay to the movement of goods, services and people and creating intolerable conditions for residents. It also suggests road improvements that would benefit the region’s economy and help to safeguard the people of Melton. Melton Parish 2. Melton is a large parish, adjacent to Woodbridge and located at the first crossing point over the tidal stretch of the River Deben, at the Wilford Bridge. Melton has a healthy jobs base with several employment areas accommodating over 150 businesses. Melton’s population has seen significant growth in recent years. There are over 1,800 dwellings in Melton Parish and an estimated population of between 4,000 and 4,275. We estimate that population has grown by about 10% in the last 4 years. Many new homes have been built recently, or are planned, along Woods Lane and other stretches of the A1152. 3. A map in Appendix A shows Melton’s geographical position relative to key transport links, the Deben Peninsula and the various locations for the SZC project. Appendix B contains a detailed map of the whole of Melton Parish and is based on its 2016 Neighbourhood Plan, updated to show recent new-builds and planning applications. -

Team Vicar in the Wilford Peninsula Team Ministry – Rendlesham Cluster PROFILE

Team Vicar in the Wilford Peninsula Team Ministry – Rendlesham Cluster PROFILE All Saints’, Eyke. St Edmund’s, Bromeswell “ Help us build our church at the “We are a living, heart of community.” lively church” St Gregory the Great, Rendlesham St Felix of Dunwich, Rendlesham St John the Baptist, Wantisden CONTENTS Page 1. Overview of the area and the Team Ministry 3 2. Introduction to the Rendlesham Cluster 6 3. Our villages – their localities and populations 7 4. Our church buildings 10 5. Strengths, opportunities and challenges 14 6. What are we looking for? what do we offer? 16 7. How we worship 18 8. Taizé worship 21 9. Youth, children, worship and pastoral care 22 10. The Ministry Team, Parochial Church Councils, supporting the church 24 11. Our mission and the Germinate initiative 25 12. The Vicarage 27 13. St Edmundsbury & Ipswich Diocese 28 Table 1: Existing pattern of services 31 Table 2: Parish statistics 32 2 1. OVERVIEW OF THE AREA AND THE TEAM MINISTRY Rendlesham Cluster is part of the Wilford Peninsula Team Ministry, which is the largest benefice in the Diocese of St Edmundsbury & Ipswich. The benefice is referred to as a Team Ministry throughout this profile. The Diocese is divided into Deaneries, overseen by two Archdeacons. Our Team Ministry, together with 5 other benefices which constitute the Woodbridge Deanery, lies in the eastern Archdeaconry of Suffolk. The Team Ministry has 17 parishes and 18 church buildings, a population of 8,500 and covers an area some 10 miles by 14 miles. Suffolk Coastal District Council is the local authority covering the area, almost all of which falls within a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). -

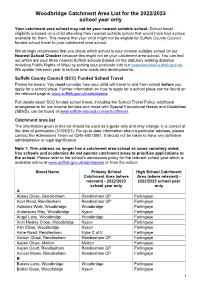

Woodbridge Catchment Area List for the 2022/2023 School Year Only

Woodbridge Catchment Area List for the 2022/2023 school year only Your catchment area school may not be your nearest suitable school. School travel eligibility is based on a child attending their nearest suitable school that would have had a place available for them. This means that your child might not be eligible for Suffolk County Council funded school travel to your catchment area school. We strongly recommend that you check which school is your nearest suitable school on our Nearest School Checker because this might not be your catchment area school. You can find out which are your three nearest Suffolk schools (based on the statutory walking distance including Public Rights of Way) by putting your postcode into our nearestschool.suffolk.gov.uk. We update this each year to include new roads and developments. Suffolk County Council (SCC) Funded School Travel Please be aware: You must consider how your child will travel to and from school before you apply for a school place. Further information on how to apply for a school place can be found on the relevant page at www.suffolk.gov.uk/admissions. Full details about SCC funded school travel, including the School Travel Policy, additional arrangements for low income families and those with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND), can be found at www.suffolkonboard.com/schooltravel. Catchment area list The information given in this list should be used as a guide only and may change. It is correct at the time of publication (31/08/21). For up-to-date information about a particular address, please contact the Admissions Team on 0345 600 0981. -

Aldringham Cum Thorpe with Sizewell Newsletter

1 Aldringham cum Thorpe with Sizewell Newsletter Website: December 2017 www.aldringham.onesuffolk.net Season’s Greetings Parish Council Update Parish Councillors Eric Atkinson Chairman 01728 830497 David Mayhew Vice-Chairman 01728 452773 Pippa McLardy 01728 454565 Scott Squirrell 01728 833691 Maureen Jones 01728 453915 Mick Sturmey 01728 452586 Alan Williams 07802 175184 Shirley Tilbrook Parish Clerk 01728 830001 Parish Council News to November 2017 Please, Mr Postman… Neighbourhood Plan (NP) Sammy and Freddy Downing from Benhall, whose dad The feasibility study to investigate the practicability of Mike works in The Dolphin, were among a number of providing affordable housing within our parish, particularly excited children who wrote letters to Father Christmas and in Thorpeness, has now started with early discussions then received a gift from the man himself while attending having taken place with SCDC and Natural England. This the Christmas Fair at the pub on November 25th. The Fair is to understand the implications of building in an area of raised around £1,000 – a fantastic sum – including £356 Outstanding Natural Beauty. Once sufficient information is from the cake stall. The proceeds will be divided between available it is planned to carry out an information event as The Heritage Group and St Andrew’s Church. part of the Neighbourhood plan development process. Congratulations to the tireless volunteers, and huge thanks to David for lending the premises. Parish Matters While on the subject of communication… Over the last couple of months, we have had a good interest in the two vacancies on the Parish Council and we In her most recent newsletter, our MP Therese Coffey has hope to fill them soon. -

Where Kings Lived Rendlesham Rediscovered

Bede, a monk at the Northumbrian Brown and Rupert Bruce-Mitford – monastery of Jarrow/Wearmouth in the excavators at Sutton Hoo – failed to early eighth century, wrote A History of locate the cemetery or any other Anglo- the English Church & People. There he Where Saxon evidence. A scatter of early and noted that Swithelm, king of the East middle Anglo-Saxon pottery was found Saxons, was baptised at the royal in 1982, in fields west and north of the settlement of Rendlesham. This must East Anglian kings of the early church; small-scale excavation have happened between ad 655 and 664. kseivnentgh cesntu lryi AvD weerd e undertaken before a barn was built Swithelm, the son of Seaxbald, was nearby revealed a ditched trackway of successor to Sigeberht. He was baptised buried with splendour at the the same date, as well as later medieval by Cedd in East Anglia [ Orientalium famous Sutton Hoo cemetery. features. There was thus archaeological Anglorum ], in the royal village [ vicus evidence for an Anglo-Saxon settlement regius ] called Rendlesham But where did they, and their at Rendlesham – but nothing to indicate [RenRdlaeshame], thant is, thed residelncee of sham rediscohigh svtatus.e red Rendil. King Aethelwold of East Anglia, families and supporters, live? This changed in 2008. The the brother of King Anna, the previous Faye Minter, Jude Plouviez landowner, Sir Michael Bunbury, wrote king of the East Angles, was his sponsor. to a local historian, concerned about (Colgrave & Mynors’ translation from and Chris Scull think they have illegal metal detectorists looting his the Latin) found the answer to this fields at night. -

Issue 103 September 2019.Pub

Rendlesham Parish Newsletter Issue 103 www.rendlesham.suffolk.gov.uk September/October, 2019 Photography Darren by Harbar Inside this issue Parish Council declares Climate Bus service reduced….. Pg 3 Emergency Parish Council news …………..…………………... Pg 5 Meet your Councillors ……………………………...Pg 6/7 Vicar’s Voice ..…..... Pg 8-11 Anglo-Saxon Rendlesham ……………………….......… Pg 15 Consumer Corner …….Pg 17 Be a Good Neighbour this Winter……………….…... Pg 20 1st Rendlesham Scouts …..………..…………...…. Pg 27 Noces & Events ..Pg 40/41 Diary dates …….….….. Pg 43 November Deadline The results of a recent children’s litter pick prompted growing concerns about the environment which contributed to Rendlesham Parish Council’s 10 October decision to declare a climate emergency. Continued on page 3 Holiday Cub rated OUTSTANDING by Ofsted on first inspection! Pitstop Out of School Club are celebrating after being awarded ‘Outstanding’ grades in all areas by Ofsted. The Holiday Club, which runs from the Deben Community Farm in Melton, was commended on their success in supporting children’s emotional well-being, exploring the natural environment and the benefits of play opportunities that challenge and complement children’s creative and physical skills exceptionally well. Photo: Photo: Pistop Rendlesham Parish Council @ RendleshamPC Page 2 Rendlesham Parish Newsletter, September/October 2019 Rendlesham Rendlesham Parish Newsletter Parish Newsletter Advertising Rates for adverts placed from 1 April 2012 CONTACTunch Advertisement For One For 3 For 6 For one EDITOR - Parish Clerk Size Month months months full Year Heather Heelis 01394 420207 E: [email protected] Business Card £8.00 £21.00 £32.00 £48.00 Views expressed in the Rendlesham Parish Newsletter are not necessarily those of the Parish Council or of other contributing 1/8(eighth) Page £13.00 £32.50 £52.00 £78.00 groups. -

Rendlesham and Orford

Street Index By District Ward Street Address Polling District District Ward name: Rendlesham & Orford ABBEY CLOSE, SUFFOLK SRORE ACER ROAD, SUFFOLK SRORE ASH ROAD, SUFFOLK SRORE ASHE ROAD, SUFFOLK SROTU ASHTON CLOSE, SUFFOLK SRORE ASPEN COURT, SUFFOLK SRORE AVOCET MEWS, SUFFOLK SRORE BAKERS LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR BARONS MEADOW, SUFFOLK SROOR BAY TREE COURT, SUFFOLK SRORE BECK CLOSE, SUFFOLK SRORE BLACKLANDS LANE, SUFFOLK SROSU BLAXHALL CHURCH ROAD, SUFFOLK SROTU BRACKEN FARM LANE, SUFFOLK SROTU BRICK KILN, SUFFOLK SROCH BROAD STREET, SUFFOLK SROOR BRUNDISH LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR BULLACE LANE, SUFFOLK SROSU BURNT LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR BUTLEY ROAD, SUFFOLK SROWA CAPTAINS WOOD, SUFFOLK SROSU CASTLE CLOSE, SUFFOLK SROOR CASTLE GREEN, SUFFOLK SROOR CASTLE HILL, SUFFOLK SROOR CASTLE LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR CASTLE TERRACE, SUFFOLK SROOR CASTLE VIEW, SUFFOLK SROOR CEDAR ROAD, SUFFOLK SRORE CHAPELFIELD, SUFFOLK SROOR CHESTNUT CLOSE, SUFFOLK SRORE CHILLESFORD LODGE ESTATE, SUFFOLK SROCH CHURCH LANE, SUFFOLK SROIK CHURCH LANE, SUFFOLK SRORE CHURCH LANE, SUFFOLK SROSU CHURCH ROAD, SUFFOLK SROBL CHURCH STREET, SUFFOLK SROOR CRAG FARM ROAD, SUFFOLK SROSU CROOKED CREEK ROAD, SUFFOLK SRORE CROWN LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR DAPHNE ROAD, SUFFOLK SROOR DOCK FARM ROAD, SUFFOLK SROTU DOCTORS LANE, SUFFOLK SROOR DRYDALE BOTTOM, SUFFOLK SROWA DUCK LANE, SUFFOLK SROTU ELM CLOSE, SUFFOLK SRORE FARNHAM ROAD, SUFFOLK SROBL FENN ROW, SUFFOLK SRORE FENN ROW, SUFFOLK SROWA FERRY ROAD, SUFFOLK SROOR FERRY ROAD, SUFFOLK SROSU FOREST GARDENS, SUFFOLK SRORE FOUNTAIN ROAD, SUFFOLK SRORE FRIDAY -

Sizewell C Community Forum Members

Sizewell C Community Forum Members Aldeburgh Town Council Cllr Suzie Osben Aldringham-Cum-Thorpe Parish Council Cllr Maureen Jones Benhall and Sternfield Parish Council Cllr David Secret Blaxhall Parish Council Cllr Jeff Hume Blythburgh Parish Council Cllr Roderick Orr-Ewing Bredfield Parish Council Cllr David Hepper Bruisyard Parish Council Cllr Anne Smith Campsea Ashe Parish Council Cllr Richard Fernley Darsham Parish Council Cllr Michael Simons Dunwich Parish Meeting Cllr Rod Smith Farnham with Stratford St Andrew Parish Council Cllr Ian Norman Friston Parish Council Cllr Mike Caplin Gt Glemham Parish Council Cllr Argus Gathorne-Hardy Hacheston Parish Council Cllr Adrian Revill Kelsale cum Carlton Parish Council Cllr Edwina Galloway Knodishall Parish Council Cllr John Staff Leiston-cum-Sizewell Town Council Cllr Lesley Hill Little Glemham Parish Council Cllr Philip Hope-Cobbold Marlesford Parish Council Cllr Richard Cooper Melton Parish Council Cllr Alan Porter Middleton Cum Fordley Parish Council Cllr Roy Dowding Nacton Parish Council Cllr Brian Hunt Parham Parish Council Cllr Andy Nicholson Peasenhall Parish Council Cllr Kenneth Parry Brown Pettistree Parish Council Cllr Jeff Hallett Rendham Parish Council Cllr Tracy Gleeson Rendlesham Parish Council Cllr Mike Stevenson Saxmundham Town Council Cllr Jeremy Smith Sibton Parish Council Cllr Allan Dale Snape Parish Council Cllr Graham Farrant Southwold Town Council Cllr Ian Bradbury Sweffling Parish Council Cllr John Tesh Theberton & Eastbridge Parish Council Cllr Stephen Brett Tunstall -

Job 120587 Type

IMMACULATE HOUSE WITH GARDENS, GARAGE & PARKING Coastguard House, Quay Street, Orford, Suffolk IP12 2NX Freehold A rare house close to the river yet with mature gardens, boat storage, a large garage & ample parking Coastguard House, Quay Street, Orford, Suffolk IP12 2NX Freehold 4 Bedrooms ◆ 3 Bath/Shower Rooms ◆ Vaulted Sitting Room ◆ Open Plan Kitchen / Dining Room / Family Room ◆ Utility Room ◆ Off Road Parking ◆ Large Garage ◆ Boat Parking ◆ Mature Gardens ◆ EPC rating = E Situation DISTANCES: Woodbridge 12.2 miles, Aldeburgh 11.4 miles, Ipswich 20.6 miles London’s Liverpool Street Station from 65 minutes Coastguard House is set in the heart of the village of Orford, a particularly sought after and attractive market town set on the banks of the River Ore. The immediate situation of Coastguard House is ideal being on Quay Street close to the facilities in the village as well as the river yet set back down a private driveway with ample off road parking. Orford benefits from numerous facilities including a sailing club, two public houses, a hotel & restaurant, a bakery and primary school. The surrounding countryside is particularly attractive with river, marshland and woodland walks within easy reach of the property. A much wider range of shopping and educational amenities can be found in the historic market town of Woodbridge set on the banks of the River Deben and also further south in Ipswich, the county town of Suffolk, which also provides a rail service to London's Liverpool Street Station. Description Coastguard House is set well back from Quay Street and has been thoroughly renovated to an exceptionally high standard throughout. -

Rushmere Mysteries NEWS Letter

Rushmere St Andrew Parish Council NEWS LETTER SPRING 2013 'SEEK THE COMMON GOOD' Rushmere mysteries There are some interesting historic features in Rushmere St Andrew that seem to be shrouded in a bit of mystery. The timber house, known as 'Columbia House', Rushmere Mill and the Old Columbia House Tollgate on Woodbridge Road near Bent Lane. The Toll Gate and the windmill can both be seen on the adjacent 1928 map. The most outstanding of these is the fine timber house known as 'Columbia House' shown in the photograph below. The story goes that it was built by local timber merchant John Brown for the Royal Agricultural Show of 1934 as an elaborate gimmick to sell timber. The then Prince of Wales attended the show and was said to have 'Taken tea in the lounge'. It seems certain that the Prince of Wales attended the 1934 show Playford and Woodbridge Roads, circa 1928 as there is a record of the visit on the I don't know, as I can't find any hard the time thought it had been transported Pathé News. evidence. Just how would one transport a from the showground. Does anyone The story however, goes on to say that house from the showground to Playford know? after the show, the house was transported Road? Perhaps it was dismantled in Over the road from Columbia House and to its present location on Playford Road. some way, or perhaps the present house down Playford Road towards Ipswich is Just how much truth there is in this is so similar to the original that people of a road called, 'The Mills'.