The University of Hull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysian-Omani Historical and Cultural Relationship: in Context of Halwa Maskat and Baju Maskat

Volume 4 Issue 12 (Mac 2021) PP. 17-27 DOI 10.35631/IJHAM.412002 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HERITAGE, ART AND MULTIMEDIA (IJHAM) www.ijham.com MALAYSIAN-OMANI HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL RELATIONSHIP: IN CONTEXT OF HALWA MASKAT AND BAJU MASKAT Rahmah Ahmad H. Osman1*, Md. Salleh Yaapar2, Elmira Akhmatove3, Fauziah Fathil4, Mohamad Firdaus Mansor Majdin5, Nabil Nadri6, Saleh Alzeheimi7 1 Dept. of Arabic Language and Literature, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 2 Ombudsman, University Sains Malaysia Email: [email protected] 3 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 4 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 5 Dept. of History and Civilization, Kulliyyah of Islamic Revealed Knowledge and Human Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia Email: [email protected] 6 University Sains Malaysia Email: [email protected] 7 Zakirat Oman & Chairman of Board of Directors, Trans Gulf Information Technology, Muscat, Oman Email: [email protected] * Corresponding Author Article Info: Abstract: Article history: The current re-emergence of global maritime activity has sparked initiative Received date:20.01.2021 from various nations in re-examining their socio-political and cultural position Revised date: 10.02. 2021 of the region. Often this self-reflection would involve the digging of the deeper Accepted date: 15.02.2021 origin and preceding past of a nation from historical references and various Published date: 03.03.2021 cultural heritage materials. -

Tengkolok As a Traditional Malay Work of Art in Malaysia: an Analysis Of

ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 19, 2020 TENGKOLOK AS A TRADITIONAL MALAY WORK OF ART IN MALAYSIA: AN ANALYSIS OF DESIGN Salina Abdul Manan1, Hamdzun Haron2,Zuliskandar Ramli3, Mohd Jamil Mat Isa4, Daeng Haliza Daeng Jamal5 ,Narimah Abd. Mutalib6 1Institut Alam dan Tamadun Melayu, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 2Pusat Citra Universiti, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 3Fakulti Seni Lukis & Seni Reka, Universiti Teknologi MARA 4Fakulti Teknologi Kreatif dan Warisan, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan 5Bukit Changgang Primary School, Banting, Selangor Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: May 2020 Revised and Accepted: August 2020 ABSTRACT: The tengkolok serves as a headdress for Malay men which have been made infamous by the royal families in their court. It is part of the formal attire or regalia prominent to a Sultan, King or the Yang DiPertuan Besar in Tanah Melayu states with a monarchy reign. As such, the tengkolok has been classified as a three-dimensional work of art. The objective of this research is to analyses the tengkolok as a magnificent piece of Malay art. This analysis is performed based on the available designs of the tengkolok derived from the Malay Sultanate in Malaysia. To illustrate this, the author uses a qualitative method of data collection in the form of writing. Results obtained showed that the tengkolok is a sublime creation of art by the Malays. This beauty is reflected in its variety of names and designs. The name and design of this headdress has proved that the Malays in Malaysia have a high degree of creativity in the creation of the tengkolok. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Syor-Syor Yang Dicadangkan Bagi Bahagian-Bahagian

SYOR-SYOR YANG DICADANGKAN BAGI BAHAGIAN-BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN DAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI PAHANG SEBAGAIMANA YANG TELAH DIKAJI SEMULA OLEH SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA DALAM TAHUN 2017 PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FEDERAL AND STATE CONSTITUENCIES FOR THE STATE OF PAHANG AS REVIEWED BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION IN 2017 PERLEMBAGAAN PERSEKUTUAN SEKSYEN 4(a) BAHAGIAN II JADUAL KETIGA BELAS SYOR-SYOR YANG DICADANGKAN BAGI BAHAGIAN-BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA PERSEKUTUAN DAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI PAHANG SEBAGAIMANA YANG TELAH DIKAJI SEMULA OLEH SURUHANJAYA PILIHAN RAYA DALAM TAHUN 2017 Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya, mengikut kehendak Fasal (2) Perkara 113 Perlembagaan Persekutuan, telah mengkaji semula pembahagian Negeri Pahang kepada bahagian- bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan dan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri setelah siasatan tempatan kali pertama dijalankan mulai 14 November 2016 hingga 15 November 2016 di bawah seksyen 5, Bahagian II, Jadual Ketiga Belas, Perlembagaan Persekutuan. 2. Berikutan dengan kajian semula itu, Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya telah memutuskan di bawah seksyen 7, Bahagian II, Jadual Ketiga Belas, Perlembagaan Persekutuan untuk menyemak semula syor-syor yang dicadangkan dan mengesyorkan dalam laporannya syor-syor yang berikut: (a) tiada perubahan bilangan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan bagi Negeri Pahang; (b) tiada perubahan bilangan bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri bagi Negeri Pahang; (c) tiada pindaan atau perubahan nama kepada bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Persekutuan dalam Negeri Pahang; dan (d) tiada pindaan atau perubahan nama kepada bahagian-bahagian pilihan raya Negeri dalam Negeri Pahang. 3. Jumlah bilangan pemilih seramai 740,023 orang dalam Daftar Pemilih semasa iaitu P.U. (B) 217/2016 yang telah diperakui oleh SPR dan diwartakan pada 13 Mei 2016 dan dibaca bersama P.U. -

1991Vol11no.2

nuasownon am roam a uunm SIX muuwsm a|.unns|:sr rmsommmcoumms "P 'i"TtE' » ~"f' ‘ ‘\ 4% , J“ W ym;.~u- »~ glhlkigsu L » “ End of War?. 2; Understanding the Gulfwu 3;AWn=B\d!tonGnml Illusions 13; ‘L Muslims my againstlmperialism. .. 1s;M=u§»§s$ mum.“ . .. 1s';1>m}>Léuv¢s T1 oftheGu1fWa!. .19;WhntCanWe Do‘?. 22;Letwrs. 23;T1mku'sQuest for Peace and ~ Unity. .. 31;O1nent Concerns. .. 36;Thinking Allowed. .. 40. 2: . THE ULFWAR All the articles on the Gulf war were written before the middle of February, with the exception of 'End of War '. This is because of the constraints that a monthly magazine like ours has to work with. Nonetheless, the editorial board hopes that the articles will enhance our understanding of what has been happening in the Gulf region and in West Asia. -EDITOR END OF WAR? t tbe time of writiD&. adlfted? If the United States' cootrol cml' puts of Iraq • lnq .. wilhdmriDI ,.. aim - a it il obrioas aow a leftw to force a c.... of A hm Kawail. It ila - il dle dellncdoa of the J0ft1111MDt Ill ....... Or, uz? till withdrawal. Tbere il lnqi mlitlry lpplntul ad Weawn coatrol Oftl', aad .. c r 11 n... n. 1Jiaimd sa.• tbe emaculadoa of rr.ideat occupatioll of, &aq may be dollaot wat a ce•eftre. Wdem au.ela't ........... Uled to coen:e other West JtWIDtltbe .... tOJOOL It ..... il ewry....,. that A.-..... - ..,....By the II ftiY c1ea' that the lJDitecl it wll coatillae the wu. Tbe IDclepeDdeat....u.decl ODel - ...... pw_.tWIJ DOt US.W cc.Udoa may try to iato acapdq ... -

Thesis Final

STATE POWER AND THE REGULATION OF NON-CITIZENS: IMMIGRATION LAWS, POLICIES, AND PRACTICES IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA ALICE MARIA NAH HAN YUONG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 STATE POWER AND THE REGULATION OF NON-CITIZENS: IMMIGRATION LAWS, POLICIES, AND PRACTICES IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA ALICE MARIA NAH HAN YUONG B.A. (Hons), University of Leeds M.Soc.Sci., National University of Singapore A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information that have been used in this thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. Alice M. Nah 14 July 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am greatly indebted to my supervisor, A/P Roxana Waterson, for her moral and intellectual support during the completion of this research. I am particularly thankful for her constant encouragement and her sensitivity in understanding how personal life sometimes ‘takes over’ during research projects. I would not have completed this work if not for her. I am grateful to the Asia Research Institute for the Research Scholarship that made this dissertation possible. At the Department of Sociology, I enjoyed learning from Professor Bryan Turner, A/P Tong Chee Kiong, and A/P Maribeth Erb, as well as tutoring for A/P Syed Farid Alatas and A/P Vineeta Sinha. I am also thankful to Dr. Nirmala PuruShotam who started me on the path of sociological research exactly a decade ago. -

2017 Annual Report

JABATAN MINERAL DAN GEOSAINS MALAYSIA DEPARTMENT OF MINERAL AND GEOSCIENCE MALAYSIA LAPORAN TAHUNAN 2017 ANNUAL REPORT KEMENTERIAN SUMBER ASLI DAN ALAM SEKITAR MALAYSIA MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT MALAYSIA Pulau Besar, Johor Pulau Harimau, Johor Kandungan Contents Perutusan Ketua Pengarah 6 Message from the Director General Profil Korporat 10 Corporate Profile Hal Ehwal Korporat 17 Corporate Affairs Kerjasama dan Perkongsian 25 Cooperation and Partnership Aktiviti Mineral 34 Mineral Activities Aktiviti Geosains 55 Geoscience Activities Aktiviti Lombong & Kuari 99 Mine and Quarry Activities Penyelidikan & Pembangunan 109 Research & Development Perkhidmatan Sokongan Teknikal 128 Technical Support Services Penerbitan 150 Publications Profil Pejabat 161 Office Profiles Sorotan Peristiwa 170 Event Highlights Senarai Pegawai Profesional 184 List of Professional Officers JAWATANKUASA EDITOR / EDITORIAL COMMITTEE PENASIHAT / ADVISORS Datuk Shahar Effendi Abdullah Azizi Kamal Daril Mohd Badzran Mat Taib Ismail Hanuar Wan Saifulbahri Wan Mohamad KETUA EDITOR / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brendawati Ismail PENOLONG KETUA EDITOR / DEPUTY CHIEF EDITOR Norshakira Ab Ghani PASUKAN EDITORIAL / EDITORIAL TEAM Hal Ehwal Korporat Ropidah Mat Zin Corporate Affairs Yusari Basiran Aktiviti Mineral Mohamad Yusof Che Sulaiman 4 Mineral Activities Mohamad Aznawi Hj Mat Awan Badrol Mohamad Jaithish John Aktiviti Geosains Muhammad Fadzli Deraman Geoscience Activities Jayawati Fanilla Sahih Montoi Muhammad Ezwan Dahlan Aktiviti Lombong & Kuari Maziadi Mamat -

Negeri : Pahang Maklumat Zon Untuk Tender Perkhidmatan

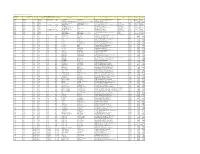

MAKLUMAT ZON UNTUK TENDER PERKHIDMATAN KEBERSIHAN BANGUNAN DAN KAWASAN BAGI KONTRAK YANG BERMULA PADA 01 JANUARI 2016 HINGGA 31 DISEMBER 2018 NEGERI : PAHANG ENROLMEN MURID KELUASAN KAWASAN PENGHUNI ASRAMA BILANGAN Luas Kaw Bil Bilangan Bilangan Bilangan Bilangan KESELURUHAN BIL NAMA DAERAH NAMA ZON BIL NAMA SEKOLAH Sekolah Penghuni Pelajar Pekerja Pekerja Pekerja PEKERJA (Ekar) Asrama (a) (b) (c) (a+b+c) 1 SMK KARAK 963 6 12 2 180 2 10 2 SMK TELEMONG 190 2 17 3 5 3 SK KARAK 636 4 7 2 6 4 SK SUNGAI DUA 223 2 10.5 2 150 2 6 1 BENTONG BENTONG 1 5 SJK(C) SG DUA 53 1 5 2 3 6 SJK(C) KARAK 415 3 3 1 4 7 SJK(C) KHAI MUN PAGI 501 4 1 1 5 8 SJK(T) LDG RENJOK 75 1 2.5 1 2 JUMLAH PEKERJA KESELURUHAN 41 1 SMK SERI PELANGAI 174 2 3 1 3 2 SK KG SHAFIE 86 1 3.5 1 2 3 SK SULAIMAN 775 5 9 2 7 2 BENTONG BENTONG 2 4 SK SIMPANG PELANGAI 216 2 5 2 4 5 SJK(C) MANCHIS 63 1 5 2 3 6 SJK(C) TELEMONG 182 2 2.5 1 3 7 SJK(T) SRI TELEMONG 41 1 2.2 1 2 JUMLAH PEKERJA KESELURUHAN 24 ENROLMEN MURID KELUASAN KAWASAN PENGHUNI ASRAMA BILANGAN Luas Kaw Bil Bilangan Bilangan Bilangan Bilangan KESELURUHAN BIL NAMA DAERAH NAMA ZON BIL NAMA SEKOLAH Sekolah Penghuni Pelajar Pekerja Pekerja Pekerja PEKERJA (Ekar) Asrama (a) (b) (c) (a+b+c) 1 SMK KARAK SETIA 225 2 8 2 4 2 SMK SERI BENTONG 542 4 34.28 4 500 3 11 3 SMK BENTONG 585 4 11.935 2 200 2 8 31 BENTONG BENTONG 31 4 SK JAMBU RIAS 161 2 1.1 1 3 5 SJK(T) KARAK 276 2 4.1 1 3 6 KIP BENUS 4 4 JUMLAH PEKERJA KESELURUHAN 33 1 SMK KETARI 1037 6 3.3 1 7 2 SMK KUALA REPAS 443 3 20.28 3 150 2 8 3 SMK KATHOLIK 475 3 3.8 1 4 4 BENTONG -

Tengkolok As the Heritage of Perak Darul Ridzuan: the Binder, Techniques, Manner & Amp; Taboo

7th International Seminar on ECOLOGY, HUMAN HABITAT AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE IN THE MALAY WORLD Pekanbaru, Riau, INDONESIA, 19-20 August 2014 Tengkolok as The Heritage of Perak Darul Ridzuan: The Binder, Techniques, Manner & Amp; Taboo Salina Abdul Manan1, Hamdzun Haron2, Zuliskandar Ramli3, Noor Hafiza Ismail4 and Rozaidi Ismail5 1) Malay World & Civilization Institute, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi,[email protected] 2) Malay World & Civilization Institute, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi,[email protected] 3) Malay World & Civilization Institute, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi,[email protected] 4) Malay World & Civilization Institute, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, [email protected] 5) Fakulti Kejuruteraan dan Alam Bina, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, [email protected] ABSTRACT Tengkolok is a unique head covering for Malay men and it is still worn to this very day.However, its adornment only is limited to certain functions and events. With this, this articleis written to document in further detail the binders of the Malay-inherited tengkolok especiallyin the state of Perak DarulRidzuan. Some questions need to be answered, such as ‘who arethe tengkolok binders in Perak?’, ‘how are the tengkolok-folding techniques used?’ and ‘whatare the etiquettes and taboo in the making of tengkolok?’. Offering explanation, aqualitative cultural approach will be adopted. Both interview and observation will be used toobtain data wither in writing or visually. The observation done has suggested that there arefour tengkolok binders who are still active in Perak. Each of them has their own respectivetengkolok folding techniques. This article will discuss the work of these binders, their foldingtechniques, the manner and etiquettes as well as the taboo in tengkolok-making. -

NEOCOMIAN PALYNOMORPH ASSEMBLAGE from CENTRAL PAHANG, MALAYSIA Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 53, June 2007, Pp

NEOCOMIAN PALYNOMORPH ASSEMBLAGE FROM CENTRAL PAHANG, MALAYSIA Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 53, June 2007, pp. 21 – 25 Neocomian palynomorph assemblage from Central Pahang, Malaysia UYOP SAID, MARAHIZAL MALIHAN AND ZAINEY KONJING Geology Programme, School of Environmental and Natural Resource Sciences Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 43600 Bangi, Selangor Darul Ehsan Abstract: The rock successions exposed at several road-cuts along the road connecting Triang and Paloh Hinai in the central part of Pahang yield a distinct palynomorph assemblage, which is dominated by fairly-well preserved significant palynomorph species namely Cicatricosisporites australiensis, C. ludbrookiae, Biretisporites eneabbaensis and Baculatisporites comaumensis. Based on the occurrence of the total palynomorphs, the identified assemblage shows some similarities with that of Stylosus Assemblage and the succeeding Speciosus Assemblage of Lower Cretaceous age. The presence of certain stratigraphically significant palynomorph permits the assignment of chronostratigraphic age of this assemblage to the lowest Speciosus Assemblage of Valanginian- Hauterivian (Neocomian). Abstrak: Jujukan batuan yang tersingkap di beberapa potongan jalan yang menghubungkan Triang dan Paloh Hinai di bahagian tengah Pahang mengandungi himpunan palinomorf yang didominasi oleh Cicatricosisporites australiensis, C. ludbrookiae, Biretisporites eneabbaensis dan Baculatisporites comaumensis yang terawet hampir sempurna. Berdasarkan kepada kehadiran -

Intercultural Theatre Praxis: Traditional Malay Theatre Meets Shakespeare's the Tempest

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2017 Intercultural theatre praxis: traditional Malay theatre meets Shakespeare's The Tempest Norzizi Zulkafli University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Zulkafli, Norzizi, Intercultural theatre praxis: traditional Malay theatre meets Shakespeare's The Tempest, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2017. -

Subject Index 99

SUBJECT INDEX 99 SUBJECTSUBJECT INDEXINDEX A B aggregate - construction Bakri see Muar under Johor Construction Aggregate Resources in the Federal Baling see Kedah Territory and Central Selangor [Cheong Khai Balingian Province see Sarawak Wing & Yeap Ee Beng , 2000] Bangi see Selangor The geology, petrography and index properties Baram delta see also Sarawak of limestone and granite aggregates for the construction industry in Central Selangor- barite Federal Territory [Cheong, K. W. & Yeap, Barite and associated massive sulphide and Fe-Mn E. B , 1999] mineralization in the Central Belt of Peninsular Malaysia [Teh Guan Hoe, 1994] apatite Occurrence and chemistry of clouded apatite from barium the Perhentian Kecil syenite, Besut, Tereng- High Ba igneous rocks from the Central Belt of ganu [Azman Abdul Ghani , 1998] Peninsular Malaysia and its implication [Azman A. Ghani, Ramesh, V Yong, B.T Khoo, T.T. art & Shafari Muda, 2002] Geoart-Turning Rocks Into Art[Lee Chai Peng, The Stratiform Volcanogenic Exhalative Barite 2000] Deposit of Jenderak, Jerantut, Pahang Da- rul Makmur [Lau, Michael, Yeap. E. B. & Astronomy Pereira, J. J., 1994] Solar Flare Activities and its Effects on the Earth [Abdul Halim Abdul Aziz, Mohd Nawawi basalts see igneous rocks Mohd Nordin & Zuhar Tuan Harith, 2002] Batu Gajah see Perak Batu Kitang see Sarawak Australia Batu Rakit see Terengganu Contaminated land - assessment and remediation Bau see Sarawak - Australian case histories [Foong, Yin- bauxite see aluminium ores kwan, 1994 Jurassic coal in Western Australia