Steve Albini Issue 43

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

Hasseltkunstencentrum Burg . Bo

. B . 1 2 / 7 4 1 3500.HASSELT.1 P BELGIE-BELGIQUE editie: juli 2010 BELGIEBELGIE KUNSTENCENTRUMKUNSTENCENTRUM BURG.BOLLENSTR.54BURG.BOLLENSTR.54 3500-HASSELT3500-HASSELT NEW RELEASES / 19’ jaargang 5X per jaar: jan-maart-mei-juli-okt / Afgiftekantoor: 3500 Hasselt 1 - P 206555 vr 1 okt 2010 SHELLAC (US) + THE EX (NL) V.U. JO LIJNEN, Burg. Bollenstraat 54, 3500 Hasselt V.U. O Winnaar Beste Cinematografie en Speciale Prijs van de Jury Sitges Internationaal Filmfestival O Winnaar Beste Cinematografie en Speciale Prijs van de Jury Sitges Internationaal Filmfestival Gouden Palm Nominatie Cannes 2009 O ENTER THE VOID(FR/DE/IT / 2009 / 35 mm / 154’) Cast Nathaniel Brown, Paz de la Huerta, Cyril Roy, Emily Alyn Lind, Jesse Kuhn, Olly Alexander... O Gouden Palm Nominatie Filmfestival van Cannes 2009 O Winnaar Beste Cinematografie en Speciale Prijs van de Jury Sitges Internationaal Filmfestival Sinds kort wonen Oscar (Nathaniel Brown) en zijn zus Linda (Paz de la Huerta) in Tokyo. Oscar leeft van de inkom- sten van kleine drugdeals en Linda werkt als stripper in een nachtclub. Tijdens een inval van de politie wordt Oscar Regie geraakt door een kogel. Hij ligt op sterven maar zijn geest, die gezworen heeft om zijn zuster nooit achter te laten, weigert de wereld van de levenden te verlaten. Tijdens de dwaaltocht van zijn geest door de stad worden de visioenen Gaspar Noé chaotischer en zijn ze een ware nachtmerrie. Het verleden, het heden en de toekomst vermengen zich in een hallucino- gene draaikolk. De in Argentinië geboren Franse regisseur Gaspar Noé schreef in 2002 filmgeschiedenis met de hondsbrutale maar uiterst vindingrijke prent Irréversible. -

Beginner's Puzzle Book

CRASS JOURNAL: A record of letters, articles, postings and e-mails, February 2009 – September 2010 concerning Penny, Gee and Allison’s ‘Crassical Collection’. 1 Mark Hodkinson Pete Wright POMONA 22nd March, 2004 Dear Mark, I was sent a copy of your book, ‘Crass - Love Songs’ by Gee recently. Having read your introduction, and the preface by Penny, I felt moved to write to you. Crass was a group functioning on consensus with the occasional veto thrown in for good measure, so I thought you might be interested in a slightly different view of the proceedings. From the nature of your introduction, I’d say that you have a pretty thorough grounding in certain aspects of the band. I’d like to broaden the context. Things were fine when we started gigging, before we had any status or influence. The main discomfort I felt and still feel about what the band promoted, started when I realised that Thatcher’s sordid right-wing laissez-faire was little different from what we were pushing. It was an unpleasant shock. Neither Thatcher nor we considered the damage done. We concentrated on the ‘plus’ side always. To say that everyone can ‘do it’, and counting it a justification when the talented, the motivated, or the plain privileged responded, while ignoring the majority who couldn’t ‘do it’, and those who got damaged trying, is a poor measure of success. Just as Putin has become the new Tzar of Russia, Crass used the well worn paths to success and influence. We had friends, people with whom we worked and cooperated. -

Komplette Ausgabe Als

HARDCOREMAGAZIN MARZ / APRIL 90 TRUST NEW ON SAINT VITUS TOXIC REASONS LP 008-68081 CD 084-68082 ON TOUR MÄRZ ’90: 4.-7. ENGLAND 8.-11. HOLLAND 12. ÜBACH-PALENBERG-ROCKFABRIK HOW IT LOOKS - HOW IT IS 13. FRANKFURT-BATSCHKAPP LP 008-68091 CD 084-68092 14. MÜNCHEN-THEATERFABRIK 16. BERLIN-SCHACHTQUALLE 17. SCHWEDEN ON TOUR APRIL ’90: 19. HAMBURG-FABRIK 20. KÖLN-ROSE CLUB 2. BERLIN ECSTASY 21. HEIDELBERG-SCHWIMMBAD 5. HAMBURG * 23. FREIBURG-CRÄSCH 6. OLDENBURG-ALHAMBRA * 24. KEMPTEN-ALLGÄUHALLE 7. ENGER-FORUM 8. KÖLN-ROSE CLUB 25. A DORNBIRN-KONKRET HOHENEMS 11. LEONBERG-BEATBARACKE 28. STUTTGART-RÖHRE 12. GAMMELSDORF-CIRCUS 29. CH BASEL-HIRSCHENECK 13. FREIBURG-JAZZHAUS 30. CH ZÜRICH-STUTZ 31. CH BERN-REITHALLE WIRD FORTGESETZT ! WIRD FORTGESETZT ! (* MIT BULLET LAVOLTA) IM VERTRIEB VON -SpV L a çï a r h r i a f a Vielen Dank für die Besprechung un- einer zivilen Bullenstreife beob- Mensch ist anscheinend beim Lesen seres Tapes in Eurer Ausgabe vom achtet zu werden. Es kam zu einer auf bestimmte Sachen Nov.89. Leider sind Euch dabei ei- Anzeige, und die Nazis mußten vor /Gruppen/Platten fixiert. Ja, was nige kleinere Fehler unterlaufen: Gericht antreten. mich noch nervt: In den "News" gibt a) Wir haben Euch nicht eine, son- Gegen den vorbestraften Braasch, es immer CD's (nur 1000 Stück), 500 dern zwei Cassetten zum Besprechen der den Wagen "nur" gefahren hatte limitierte 7", usw. O.k., ich nehms geschickt. (unseres Erachtens aber der Initia- zu 2/3 wieder zurück. Der Rest ist b) Diese beiden Cassetten sind tor dieser Aktion war!), wurde sein in den Anzeigen, nicht nur bei keine Demos, sondern Sampler, die Verfahren schon im Vorwege einge- Euch. -

Big Black Pigpile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Black Pigpile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pigpile Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Industrial, Noise MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1934 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 569 Other Formats: MMF VOX ADX MP2 XM MP4 AIFF Tracklist A1 Fists Of Love A2 L Dopa A3 Passing Complexion A4 Dead Billy A5 Cables A6 Bad Penny B1 Pavement Saw B2 Kerosene B3 Steelworker B4 Pigeon Kill B5 Fish Fry B6 Jordan, Minnesota Companies, etc. Record Company – Southern Studios Ltd. Pressed By – MPO Recorded At – Hammersmith Clarendon Notes Recorded at the Hammersmith Clarendon, London, England in Summer 1987. White label in plain white sleeve with New Release letter from Southern Studios, London which has typed tracklist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side A): MPO TG 81 A1 "A Dearth of Jon Spencer or What?" Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side B): MPO TG 81 B1 "Please Increase Playback Volume 2db" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, TP) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81C Big Black Pigpile (Cass) Touch And Go TG81C US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, RP) Touch And Go TG81 US Unknown SENTO YU-1 Big Black Pigpile (CD, Album) Sento SENTO YU-1 Japan 1992 Related Music albums to Pigpile by Big Black Clash, The - (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais Alexander O'Neal - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo - London Balaam And The Angel - Live At The Clarendon Venom - Fuckin' Hell At Hammersmith The Human League - London Hammersmith Palais 22.5.80 Killing Joke - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo 16.10.2010 Volume 1 Motörhead - No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith Danzig - Die Die My Darling Big Black - Songs About Fucking Venom - Live In Hammersmith Odeon London 08.10.85. -

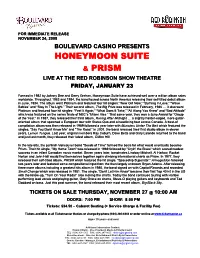

Honeymoon Suite & Prism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 24, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS HONEYMOON SUITE & PRISM LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23 Formed in 1982 by Johnny Dee and Derry Grehan, Honeymoon Suite have achieved well over a million album sales worldwide. Throughout 1983 and 1984, the band toured across North America releasing their self-titled debut album in June, 1984. The album went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “New Girl Now,” “Burning In Love,” “Wave Babies” and “Stay In The Light.” Their second album, The Big Prize was released in February, 1986 … it also went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “Feel It Again,” “What Does It Take,” “All Along You Knew” and “Bad Attitude” which was featured on the series finale of NBC’s “Miami Vice.” That same year, they won a Juno Award for “Group of the Year.” In 1987, they released their third album, Racing After Midnight … a slightly harder-edged, more guitar- oriented album that spawned a European tour with Status Quo and a headlining tour across Canada. A best-of compilation album was then released in 1989 followed a year later with Monsters Under The Bed which featured the singles, “Say You Don’t Know Me” and “The Road.” In 2001, the band released their first studio album in eleven years, Lemon Tongue. Last year, original members Ray Coburn, Dave Betts and Gary Lalonde returned to the band and just last month, they released their latest album, Clifton Hill. In the late 60s, the punkish Vancouver band "Seeds of Time" formed the basis for what would eventually become Prism. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

A Nickel for Music in the Early 1900'S

A Nickel for Music in the Early 1900’s © 2015 Rick Crandall Evolution of the American Orchestrion Leading to the Coinola SO “Super Orchestrion” The Genesis of Mechanical Music The idea of automatic musical devices can be traced back many centuries. The use of pinned barrels to operate organ pipes and percussion mechanisms (such as striking bells in a clock) was perfected long before the invention of the piano. These devices were later extended to operate music boxes, using a set of tuned metal teeth plucked by a rotating pinned cylinder or a perforated metal disc. Then pneumatically- controlled machines programmed from a punched paper roll became a new technology platform that enabled a much broader range of instrumentation and expression. During the period 1910 to 1925 the sophistication of automatic music instruments ramped up dramatically proving the great scalability of pneumatic actions and the responsiveness of air pressure and vacuum. Usually the piano was at the core but on larger machines a dozen or more additional instruments were added and controlled from increasingly complicated music rolls. An early example is the organ. The power for the notes is provided by air from a bellows, and the player device only has to operate a valve to control the available air. Internal view of the Coinola SO “orchestrion,” the For motive most instrumented of all American-made machines. power the Photo from The Golden Age of Automatic Instruments early ©2001 Arthur A. Reblitz, used with permission. instruments were hand -cranked and the music “program” was usually a pinned barrel. The 'player' device became viable in the 1870s. -

La Top 50 Di Kurt La Top 50 Di Kurt

Cobain e Novoselic fondano la prima band Pagina accanto: I Nirvana fotografati a Seattle sognando di fare cover dei Creedence nel maggio 1988. Da sinistra: il batterista Clearwater Revival. Chad Channing, Novoselic e Cobain. Charles Peterson/Retna Ltd./Corbis più ampio e, anche se nell’ordine delle decine di persone, è un pubblico costante. I Nirvana ampliano LA TOP il proprio territorio fino a Olympia e a qualche accordi lavorativi (è l’unico con un diploma di scuola concerto sporadico a Seattle. Jack Endino rimane superiore), ma questa volta si presenta tracannando 50 DI sufficientemente colpito dal loro demo tape da LA TOP una bottiglia di vino. Cobain è estremamente nervoso e darne una copia a un DJ della KCMU, la stazione chiuso. Poneman gli offre un contratto discografico, ma KURT radio dell’Università di Washington, che comincia a 50 DI per produrre un singolo e con un compenso che copre trasmettere una delle tracce. solo le spese di registrazione. Peggio ancora, Poneman è SCRATCH ACID Endino consegna una copia del demo anche a KURT interessato esclusivamente a “Love Buzz,” l’unica canzone Scratch Acid EP (Rabid Cat, 1984) Jonathan Poneman che, col socio Bruce Pavitt, ha in scaletta che non è stata critta da Cobain. Eppure, alla La band degli Scratch Acid (gran nome, qualsiasi fondato la Sub Pop Records. La scena musicale di SACCHARINE TRUST fine dell’incontro, i Nirvana accettano l’accordo, concluso cosa significhi) prende il suono dei colleghi texani EP (SST, 1981) Butthole Surfers, lo intreccia con un’intensa e Seattle è ancora dominata dalle cover band, ma la Sub Paganicons con una stretta di mano, e la band fissa una nuova sessione La nascita e lo sviluppo dell’hardcore tradizionale irritante affinità coi Birthday Party di Nick Cae Pop comincia ad avere un successo contenuto con le di registrazione con Endino. -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

The BG News October 8, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-8-1993 The BG News October 8, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 8, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5585. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5585 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ^ The BG News Friday, October 8, 1993 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 76, Issue 32 Briefs Somalia gets more U.S. backup by Terence Hunt months" to complete the mission ness and chaos. He noted Clin- Weather The Associated Press but he hoped to wrap it up before ton's statement that there la no then. guarantee Somalia will rid itself Aspin said he hoped Clinton's of violence or suffering "but at Friday: Mostly sunny. WASHINGTON - President "We started this mission for the High 75 to 80. Winds south 5 decision would lead other nations least we will have given Somalia Clinton told the American people right reasons and we are going to to beef up their forces in Soma- a reasonable chance." to IS mph. Thursday he was sending 1,700 Friday night: Partly lia. "We believe the allies will Aspin defended himself more troops, heavy armor and finish it in the right way.