Between the Hero and the Shadow: Developmental Differences in Adolescents’ Perceptions and Understanding of Mythic Themes in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8Th Grade Optional Summer Reading Book List

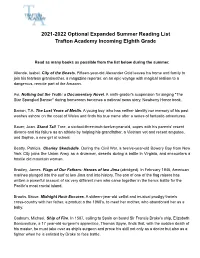

2021-2022 Optional Expanded Summer Reading List Trafton Academy Incoming Eighth Grade Read as many books as possible from the list below during the summer. Allende, Isabel. City of the Beasts. Fifteen-year-old Alexander Cold leaves his home and family to join his fearless grandmother, a magazine reporter, on an epic voyage with magical realism to a dangerous, remote part of the Amazon. Avi. Nothing but the Truth: a Documentary Novel. A ninth-grader's suspension for singing "The Star Spangled Banner" during homeroom becomes a national news story. Newberry Honor book. Barron, T.A. The Lost Years of Merlin. A young boy who has neither identity nor memory of his past washes ashore on the coast of Wales and finds his true name after a series of fantastic adventures. Bauer, Joan. Stand Tall. Tree, a six-foot-three-inch-twelve-year-old, copes with his parents' recent divorce and his failure as an athlete by helping his grandfather, a Vietnam vet and recent amputee, and Sophie, a new girl at school. Beatty, Patricia. Charley Skedaddle. During the Civil War, a twelve-year-old Bowery Boy from New York City joins the Union Army as a drummer, deserts during a battle in Virginia, and encounters a hostile old mountain woman. Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers: Heroes of Iwo Jima (abridged). In February 1945, American marines plunged into the surf at Iwo Jima and into history. The son of one of the flag raisers has written a powerful account of six very different men who came together in the heroic battle for the Pacific's most crucial island. -

Title Summary Review Between Shades of Gray Bluefish

Title Summary Review Sepetys’ first novel offers a harrowing and horrifying account of the forcible relocation of countless Lithuanians in the wake of the Russian invasion of their country in 1939. In the case of 15-year-old Lina, her mother, and her younger brother, this means deportation to a forced-labor camp in Siberia, where conditions are all too painfully similar to those of Nazi concentration camps. By Ruta Sepetys: In 1941, fifteen- Lina’s great hope is that somehow her father, who has already been arrested by the Soviet secret police, might find and rescue year-old Lina, her mother, and them. A gifted artist, she begins secretly creating pictures that can—she hopes—be surreptitiously sent to him in his own prison brother are pulled from their camp. Whether or not this will be possible, it is her art that will be her salvation, helping her to retain her identity, her dignity, Lithuanian home by Soviet guards and her increasingly tenuous hold on hope for the future. Many others are not so fortunate. Sepetys, the daughter of a Lithuanian and sent to Siberia. refugee, estimates that the Baltic States lost more than one-third of their populations during the Russian genocide. Though many continue to deny this happened, Sepetys’ beautifully written and deeply felt novel proves the reality is otherwise. Hers is an important book that deserves the widest possible readership. *William C. Morris Award Finalist *YALSA Top Ten Fiction Award Between Shades of Gray (Booklist) Historical Fiction 344 pages UG By Pat Schmatz: Thirteen-year-old Travis, living in cramped quarters Travis lives with his alcoholic grandfather and his beloved dog, Rosco. -

Exhibition Preview

Exhibition Preview Big blue skies, rugged canyons, loyal horses, damsels in distress, ruthless gunslingers, savage Indians and handsome but tormented men wearing cowboy hats. Yep, that just about describes the premise for many western films and televisions shows of Hollywood’s golden age. This exhibition peels back some of the history, mythology and popular culture layers to reveal the Western genre as ongoing narrative source for scholars, artists and film makers. The artworks, memorabilia, music and historical displays celebrate the nostalgia tied to the western genre and expose the facts and fiction about morality, race relations and economics in a complicated story that is the history of the American West. Featured Artists: Dick Ayers, Thomas Hart Benton, Charles Braden, Brose Brothers Productions, Anne Coe, Rita Consing, Dwayne Hall, Luis Alfonzo Jimenez, Richard Lillis, Lon Megargee, Ed Mell, Douglas Miles, Mark Newport, William Clinton Schenk and Fritz Scholder. Thank you: ASU Art Museum, ASU Center for Film and Popular Culture, Rolf Brown, Michael Collier Gallery, Michael Ging, Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, Phoenix Film Festival, Tempe History Museum and Dr. Larry and Holley Thompson. The following slides highlight some of the contemporary Arizona-based artists in the exhibition. Rita Consing, Phoenix Rita Consing The Lone Ranger and The Lone Ranger 2, 2017 acrylics on canvases Consing is a Philippine American artist. Her father was an artist and the family spent a lot of time traveling the world. She was exposed to a lot of different cultures and recalls being influenced images of Ninjas, Samurais and Bruce Lee in Asia while enjoying the American comic books and western reruns like “The Lone Ranger” in the West. -

Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Chris Yogerst University of Wisconsin - Washington County, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 18 Article 7 Issue 2 October 2014 10-1-2014 Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Chris Yogerst University of Wisconsin - Washington County, [email protected] Recommended Citation Yogerst, Chris (2014) "Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol18/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Abstract This essay explores how the original Indiana Jones trilogy (Raiders of the Lost Ark, Temple of Doom, and The Last Crusade) work as a single journey towards faith. In the first film, Indy fully rejects religion and by the third film he accepts God. How does this happen? Indy takes a journey by exploring archeology, mythology, and theology that is best exemplified by Joseph Campbell's The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Like many people who come to find faith, it does not occur overnight. Indy takes a similar path, using his career and adventurer status to help him find Ultimate Truth. Keywords Indiana Jones, Steven Spielberg, Hollywood, Faith, Radiers of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom Author Notes Chris Yogerst teaches film and communication courses for the University of Wisconsin Colleges and Concordia University Wisconsin. -

A Portfolio of Thoughts, Analysis, Notes, Art, Etc

McNair 1 from Writing 135-01; Living in the Age of the Antihero a Portfolio of thoughts, analysis, notes, art, etc. Written, Edited, and Compiled by Eliza McNair McNair 2 Table of Contents: Table of Contents - page 1 Introduction - pages 2-3 Blog 1: A Hope in Hell – Setting the Scene - pages 4-5 Assignment 1: The Personification and Characterization of Hell - pages 5-11 Blog 2: Batman – Black, White, and Shades of Gray - pages 12-13 Blog 3: Tender Indifference - pages 13-15 Assignment 2: Analyzing The Outsider Using its Triangular Character Structure - pages 15-21 Blog 4: Time and Shadows, Forward and Backwards - pages 22-23 Blog 5: Speculation, Dystopia, and “The Dead Poets Society” - pages 23-24 Assignment 3: How Monsters can be more Human than Humans - pages 25-34 Zine: Triquetra - (Sheet Protector Insert) Conclusion - pages 35-37 Works Cited - page 38-39 “The way to create art is to burn and destroy ordinary concepts and to substitute them with new truths that run down from the top of the head and out of the heart.” — Charles Bukowski McNair 3 Introduction: Dear Reader, This collection of blog posts and essays documents my changing understanding of antiheroes as this semester progressed. When classes started this past September, my view of antiheroes was limited to reflections on my favorite Marvel characters and Disney’s infamous Captain Jack Sparrow. Reading through the syllabus, I thought that my favorite texts and media from the class would be Frank Miller’s Batman and Joss Whedon’s Buffy both because they were familiar and because they seemed to have obvious antiheroic characters. -

8Th Grade Suggested Summer Reading 2017

8th grade Suggested Summer Reading 2017 Realistic Ficton Laurie Halse Anderson: Wintergirls (278p) Kelly Bingham: Shark Girl (276p) Stephen Chbosky: The Perks of Being a Wallflower (213p) Susane Colasanti: Keep Holding On (202p) and others Sarah Dessin: Saint Anything (432p) and others Gayle Forman: If I Stay (259p), Where She Went Jack Gantos: Dead End in Norvelt (341p) and sequel John Green: The Fault in Our Stars (318 p), PaperTown (305p) Tim Green: New Kid (307p) and others Jenny Han: The Summer I Turned Pretty (276p) an sequels Thatcher Heldring: Roy Morelli Steps up to the Plate (229p) Carl Hiaassen: Hoot (292p), Flush, Scat, Chomp Mark Peter Hughes: Lemonade Mouth (338p) Gordon Korman: Ungifted (280p) Mike Lupica: True Legend (292p) and others Frances O'Roark Dowell: Chicken Boy (201p) Julie Anne Peters: Define Normal Dana Reinhardt: Things a Brother Knows (256p) Rainbow Rowell: Eleanor & Park (325p), Fangirl Gary Schmidt: First Boy (205p) Neal Shusterman: Antsy does Time(247p), The Schwa was Here Jennifer E. Smith: The Statistical Probability of Falling in Love at First Sight (236p) Jordon Sonneblick: Zen and the Art of Faking It (264), After Ever After and others Jerry Spinelli: Wringer Cynthia Voigt: Homecoming (312p) Gabrielle Zevin: Elsewhere (275p) Historical Fiction Laurie Halse Anderson: Chains(316p), Forge, Fever, 1793 Sam Angus: Soldier Dog Susan Campbell Bartoletti: The Boy Who Dared (202p) John Boyne: The Boy in the Striped Pajamas: a Fable (215p) Joseph Bruchac: Code Talker: a Novel About the Navajo Marines of World War Two (231p) Carole Estby Dagg: The Year We Were Famous Karen Hesse: Stowaway Gennifer Choldenko : Al Capone Does My Shirts (225p) and sequels Karen Cushman: The Loud Silence of Francine Green (225p) Alice Hoffman: Incantation Jennifer L. -

Outside / Summer Reading List Hardin Valley Academy 2018-2019 If There Are Objections to Any of the Selected Texts Stemming From

Outside / Summer Reading List Hardin Valley Academy 2018-2019 If there are objections to any of the selected texts stemming from language, religious beliefs, or other controversial subject matter, alternate titles are available upon request. Please Note: HVA made a change last year that requires students in CP English classes to read two novels. The first, a graphic novel, is mandatory. For their second novel, they may choose any of the three other novels listed for their grade level. Mandatory Read: Flying Couch: A Graphic Memoir – Amy Kurzweil 9 CP Also, Choose One Among: Unbroken: An Olympian’s Journey from Airman to Castaway to Captive (YA Adaptation) – Laura Hillenbrand Between Shades of Gray – Rupta Sepetys Code Name Verity – Elizabeth Wein* Mandatory Reads: 9 Honors Antigone – Sophocles Frankenstein – Mary Shelley Things Fall Apart – Chinua Achebe Mandatory Read: American Born Chinese – Gene Luen Yang 10 CP Also, Choose One Among: The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates – Wes Moore Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe – Benjamin Alire Sáenz* Mosquitoland – David Arnold* Mandatory Reads: 10 Honors Brave New World – Aldous Huxley* Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen How to Read Literature Like a Professor – Thomas Foster* Mandatory Read: March: Book One – John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell 11 CP Also, Choose One Among: I am Malala – Malala Yousafzai The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks – E. Lockhart The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – Mark Twain* Mandatory Reads: 11 AP Lit. The Great Gatsby – F. Scott Fitzgerald A Raisin in the Sun – Lorraine Hansberry* Mandatory Read: Steve Jobs: Insanely Great – Jesse Hartland 12 CP Also, Choose One Among: The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II – Denise Kiernan The Adoration of Jenna Fox – Mary E. -

TECH TIMES for Yokohama Real Hoopties of New Jersey @ NJMP (June 11)

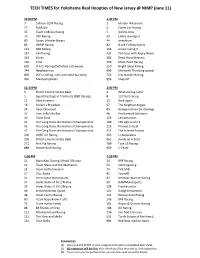

TECH TIMES for Yokohama Real Hoopties of New Jersey @ NJMP (June 11) 12:00 PM 1:30 PM 7 Lilliston CDJR Racing 2 Murder Whorenet 27 BoMoGe 4 Flame Car Racing 35 Team C Minus Racing 5 Duhhh-kota 70 CRP Racing 29 Elmos revenge 2 80 Soapy Wooder Racers 44 wrecktum 83 HBHIP Racing 82 B.A.R.F Motorsports 123 SBD Racing 166 sinical racing 3 187 EJH Racing 424 Old Guys with Angry Wives 322 8 hiks 482 Dead Horse Beaters 336 4.Ho 496 Moot Point Racing 605 D.A.D. Racing (Definitely a Daewoo) 510 Bright Ideas Racing 744 Neighborinos 699 Martinelli Plumbing special 800 We're calling…cars extended warranty 715 Cup Noodle Racing 996 Mazdastopheles 856 Snap-off 12:30 PM 2:00 PM 0 British Empire Strikes Back 3 What are lug nuts? 1 Squatting Dogs In Tracksuits (SBD Racing) 8 1/2 fasst racing 12 Afterbummer 22 Back Again 18 Occam’s Breadvan 67 The Knighted Angels 26 Apex Obsessed 85 Garage Heroes (in training) 37 Tom Tully's Buillac 96 Pro Bandaid Solutions 40 Team Duty 155 Lemontarians 41 The Gang Ruins the National Championship 199 FRS Ugly Uncle 2 42 The Gang Ruins the National Championship 235 Prompt Critical 43 The Gang Ruins the National Championship 314 The Science Project 106 UnFIT for Racing 363 L chupacabra 206 British Empire Strikes Back 461 Dumb As A Brick 272 Pink Pig Racing 789 Fuse 15 Racing 888 Mome Rath Racing 969 C-Team 1:00 PM 2:30 PM 11 MarioKart Driving School //Bratva 34 BRF Racing 13 Team Mean and the Mechanics 54 Somtingwong 14 Team Farfrumwinnin 74 THE MIB 17 Glue Sticks 81 TeamXR 21 Interceptor Motorsports 84 Altimate Warrior Racing 31 Great Globs of Oil //Bratva 90 HAMMotorsports 33 Great Globs of Oil //Bratva 108 Frankenvette 46 Brooklyn Bomb Squad 125 Gadget Inspectors 48 Great Carma Racing 131 Rescue Auto Racing 60 Team Napa know it all's 143 BRF Racing 72 Team mallet heads 181 Hopes & Dreams Racing 88 88 Shades of Gray 188 AA Racing 111 Monkey House Racing 196 Our Mid Life Crisis 121 The Slow and Mello 531 Turtle Eclipse of the Heart_ 151 Glue Sticks 984 Bob Ross Alaskan Spirit. -

Language Arts Resources Used

CURRENT LIST OF SECONDARY (6-12) LANGUAGE ARTS RESOURCES USED Northfield Public Schools September 26, 2011 Grade 6 Language Arts READING READING (continued) READING (continued) Novels: Novels (continued): Text/Anthologies: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Phoenix Rising (Have to look up the name.) A Long Way From Chicago Pinballs A Wrinkle in Time Rascal Across Five Aprils Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry Teacher Resources: Banner in the Sky Running Out of Time (*5th) Trade Book Teacher Edition Birchbark House Sarah, Plain and Tall Resource Books – Novel Guides Bridge to Terabithia (*5th) Shades of Gray Chasing Vermeer Shane Cricket in Times Square (Amis.) Sherlock Holmes Mysteries WRITING Daniel’s Story Shiloh Dear Mr. Henshaw Sign of the Beaver Text: Dicey’s Song Soldier’s Heart Write Source Dog Song Sounder Rebecca Sitton Spelling Everything on a Waffle Summer of Swans Esperanza Rising (Amistades) The Breadwinner Grammar: Farewell to Manzanar The Cay Write Source Freak the Mighty The Giver Rebecca Sitton Friedrich True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle Friendship and Gold Cadillac Tuck Everlasting Spelling: Gathering Blue Walk Two Moons th 6-8 List of Priority Spelling Words in Hank the Cowdog (*5 ) Westing Game Write Source Hatchet When the Tripods Came Rebecca Sitton Spelling How to Eat Fried Worms Wishgiver Incredible Journey Woodsong Lion’s Paw Island Far from Home Vocabulary: Island of Blue Dolphins Journey to Johannesburg Plays: Julie of the Wolves Teacher Resources: Last of the Really Great Whangdoodles Rebecca Sitton Spelling Little House on the Prairie Write Source Maniac Magee Short Stories: Max the Mighty Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of Mud City Poetry: SPEAKING, LISTENING, AND My Side of the Mountain A Joyful Noise VIEWING Nimh (*5th) Poetry Out Loud Number the Stars Heritage Readers (Johnstone) Text: Olive’s Ocean On My Honor Painting the Dakota Nonfiction: Video/Audio Parvana’s Journey Core Texts: (Do not use at other grade levels.) Northfield Public Schools Updated 9/26/2011 GRADE 6 CLASSROOM LIBRARY TITLES Biographies That Are Not Boring (Book Set): 1. -

An Educator's Guide to Ruta Sepetys

An Educator’s Guide to RUTA SEPETYS Connecting history to ourselves through Young Adult Literature THE ACTIVITIES IN THIS GUIDE ALIGN WITH COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS AND FIT INTO THE CURRICULUM FOR GRADES 7-10 1 Dear Educator, History is mankind’s most essential mode of storytelling. Prehistoric cave paintings, ancient chronicles, scholarly studies of historical evidence, multimedia productions, and of course today’s social media timelines, walls, feeds, and stories . our fascination with the rich and dynamic forms of the human experience is one of our most basic interests. Historical fiction can be a powerful transition into a deeper understanding of history, offering learners a personalized experience as a scaffold for building a more purposeful study of therealities beyond the fiction. This guide is designed as a comprehensive teaching tool for educators’ use of Sepetys’ novels in the classroom. Teachers who use only one of the novels will find pre-reading activities, discussion questions, research projects, and prompts specific to each novel. In addition, the guide is designed so that educators may also utilize literature circles in the classroom, allowing for more than one of these books to be used simultaneously. In this model, each student selects one of the books to read independently. During class time, students are divided into reading groups for each novel. Common Core curricular objectives ask that students read and comprehend complex texts independently and proficiently. Both student choice in reading and small group discussion contribute to a positive experience for students. You will find pre-reading activities that can apply to all of the novels, as well as post-reading prompts that invite cross-text comparisons. -

A Cultural Perspective on the Sexualizing of Male Villains and Antiheroes in Film and Television Amanda Jobes Elizabethtown College, [email protected]

Elizabethtown College JayScholar English: Student Scholarship & Creative Works English Spring 2019 Society's Changing Values: A Cultural Perspective on the Sexualizing of Male Villains and Antiheroes in Film and Television Amanda Jobes Elizabethtown College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://jayscholar.etown.edu/englstu Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jobes, Amanda, "Society's Changing Values: A Cultural Perspective on the Sexualizing of Male Villains and Antiheroes in Film and Television" (2019). English: Student Scholarship & Creative Works. 3. https://jayscholar.etown.edu/englstu/3 This Student Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the English at JayScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English: Student Scholarship & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of JayScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elizabethtown College Society’s Changing Values: A Perspective on the Sexualizing of Male Villains and Anti-heroes in Film and Television Amanda Jobes English Honors in the Discipline May, 2019 2 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….Page 3 Pre-Discussion: The Thin Line Between Good and Evil……………………………....Page 6 Part I: Captain Jack Sparrow…………………………………………………………...Page 17 Part II: Loki of Asgard…………………………………………………………………Page 26 Part III: Lucifer Morningstar…………………………………………………………...Page 35 Part IV: Damon Salvatore……………………………………………………………...Page 49 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...Page 61 Primary Sources………………………………………………………………………..Page 64 Secondary Sources……………………………………………………………………..Page 65 Works Consulted……………………………………………………………………….Page 68 3 Introduction As human beings, many of us are attracted to what we cannot, or should not, have. We are inclined to have that last slice of cake, to venture into unknown territory, or to fall in love with someone we know will disappoint us. -

Pre-AP/AP/DUAL English Required Summer Reading for Students Entering Grades 9-12 2020-2021

Pre-AP/AP/DUAL English Required Summer Reading for Students Entering Grades 9-12 2020-2021 Dear Cleburne Jacket Pre-AP/Ap/Dual Parents and Guardians, CISD requires students who are enrolled in Pre-AP ELAR to read over the summer. For ALL students, reading over the summer has many benefits: ● Support student’s growth ● Improves vocabulary ● Improves comprehension ● Improves test scores ● Improves writing skills Summer reading exposes students to quality literature that they may not pick up on their own and promotes independent reading, inquiry, and scholarship which will facilitate students as lifelong learners. Expectations for assignments are common across campuses within the district. Within the first three weeks of school, students will be expected to demonstrate understanding of the reading they have completed, so completion of reading prior to the first day of school is highly recommended. Students will receive an assignment grade for the work they complete over their chosen book within the first six weeks of school. A book list is attached and will also be available on the district and school websites. As students read this summer, it is highly encouraged that they annotate their books to help them develop good reading habits and comprehend the text. Teachers will have more information regarding the tasks for response to reading that will be sent out via email/web page. Any questions or concerns regarding the summer reading requirements should be directed to the Pre-AP/AP/DUAL campus teacher or the CISD ELAR Curriculum Coordinator. Respectfully, Belen Morgan CISD ELAR Curriculum Coordinator CISD 2020-21 EI Grade Choices Students entering Grade 9 Pre-AP will read any one book from the following: 1.