A Portfolio of Thoughts, Analysis, Notes, Art, Etc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lie of the Land' by Toby Whithouse - TONE DRAFT - 22/11/16 1 PUBLIC INFORMATION FILM

DOCTOR WHO SERIES 10 EPISODE 8 "X" by Toby Whithouse TONE DRAFT (DRAFT TWO) 22/11/16 (SHOOTING BLOCK 6) DW10: EP 8 'The Lie of the Land' by Toby Whithouse - TONE DRAFT - 22/11/16 1 PUBLIC INFORMATION FILM. 1 Space. The sun rising over the peaceful blue Earth. VOICE OVER The Monks have been with us from the beginning. Primordial soup: a fish heaves itself from the swamp, its little fins work like pistons to drag itself up the bank, across the sandy earth. The most important and monumental struggle in the planet’s history. It bumps into the foot of a Monk, waiting for it. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They shepherded humanity through its formative years, gently guiding and encouraging. Cave paintings: primitive man. Before them, what can only be a Monk. It holds a spear, presenting it to the tribe of men. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) Like a parent clapping their hands at a baby's first steps. Another cave painting: a herd of buffalo, pursued by the men, spears and arrows protruding from their hides. Above and to the right, watching, two Monks. Benign sentinels. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They have been instrumental in all the advances of technology and culture. Photograph: Edison, holding a lightbulb. The arm and shoulder of a Monk next to him, creeping into the frame. VOICE OVER (CONT’D) They watched proudly as man invented the lightbulb, the telephone, the internet... Photograph: the iconic shot of Einstein halfway through writing the equation for the theory of relativity on a blackboard. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

HILLS to HAWKESBURY CLASSIFIEDS Support Your Local Community’S Businesses

September 18 - October 4 Volume 32 - Issue 19 THE HAWKESBURY RIVER BRIDGE is part of the Sydney Trains rail network. The bridge is a multi-span underbridge located at 58.46 km on the Main North Line. It was constructed around 1945, adjacent to the original 1889 structure which it replaced. The main river spans consist of a variety of steel through trusses with concrete land spans. The substructure consists of two abutments on shallow foundations and nine piers supported by caissons bedded into the river soil or rock. Underwater inspections are undertaken every six years as part of ST’s bridge management program. The most recent underwater inspection was in May MARK VINT Motorcycles 2013. Results identified significant deterioration Suitable for Wrecking on the top of the downstream reinforced concrete 9651 2182 cylinder of pier no 2, including concrete section loss Any Condition 270 New Line Road of up to 750mm in the zone directly underneath the Dural NSW 2158 Dirt, MX, Farm, 4x4 marrying slab. [email protected] ABN: 84 451 806 754 Wreckers Opening Soon Sydney Trains is reviewing its options to fix these WWW.DURALAUTO.COM 0428 266 040 issues. “Can you keep my dog from Gentle Dental Care For Your Whole Family. Sandstone getting out?” Two for the price of One Sales Check-up and Cleans Buy Direct From the Quarry Ph 9680 2400 When you mention this ad. Come & meet 432 Old Northern Rd vid 9652 1783 Call for a Booking Now! Dr Da Glenhaven Ager Handsplit Opposite Flower Power It’s time for your Spring Clean ! Random Flagging $55m2 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie C & M AUTO’S Free ONE STOP SHOP battery Let us turn your tired car into a backup when you mention finely tuned “Road Runner” “We Certainly Can!” this ad ~ Rego Checks including Duel Fuel, LPG Inspections & Repairs BOUTIQUE FURNITURE AND GIFTS ~ New Car Servicing ~ All Fleet Servicing ~ All General Repairs (Cars, Trucks & 4WD) A. -

Super Satan: Milton’S Devil in Contemporary Comics

Super Satan: Milton’s Devil in Contemporary Comics By Shereen Siwpersad A Thesis Submitted to Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MA English Literary Studies July, 2014, Leiden, the Netherlands First Reader: Dr. J.F.D. van Dijkhuizen Second Reader: Dr. E.J. van Leeuwen Date: 1 July 2014 Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………... 1 - 5 1. Milton’s Satan as the modern superhero in comics ……………………………….. 6 1.1 The conventions of mission, powers and identity ………………………... 6 1.2 The history of the modern superhero ……………………………………... 7 1.3 Religion and the Miltonic Satan in comics ……………………………….. 8 1.4 Mission, powers and identity in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost …………. 8 - 12 1.5 Authority, defiance and the Miltonic Satan in comics …………………… 12 - 15 1.6 The human Satan in comics ……………………………………………… 15 - 17 2. Ambiguous representations of Milton’s Satan in Steve Orlando’s Paradise Lost ... 18 2.1 Visual representations of the heroic Satan ……………………………….. 18 - 20 2.2 Symbolic colors and black gutters ……………………………………….. 20 - 23 2.3 Orlando’s representation of the meteor simile …………………………… 23 2.4 Ambiguous linguistic representations of Satan …………………………... 24 - 25 2.5 Ambiguity and discrepancy between linguistic and visual codes ………... 25 - 26 3. Lucifer Morningstar: Obedience, authority and nihilism …………………………. 27 3.1 Lucifer’s rejection of authority ………………………..…………………. 27 - 32 3.2 The absence of a theodicy ………………………………………………... 32 - 35 3.3 Carey’s flawed and amoral God ………………………………………….. 35 - 36 3.4 The implications of existential and metaphysical nihilism ……………….. 36 - 41 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………. 42 - 46 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.1 ……………………………………………………………………… 47 Figure 1.2 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.3 ……………………………………………………………………… 48 Figure 1.4 ………………………………………………………………………. -

BBC 3 Final 18/7/06 14:02 Page 7

BBC 3 Final 18/7/06 14:02 Page 7 03 04 BBC 3 Final 18/7/06 14:02 Page 9 TORCHWOOD Torchwood follows the adventures of a team of investigators as they use alien technology to solve crimes, both alien and human. This new British sci-fi crime thriller, from Russell T Davies, follows the team as they delve into the unknown. They are fighting the impossible while keeping their everyday lives going back at home. The cast includes John Barrowman (Doctor Who) as the enigmatic Captain Jack Harkness, the ever-watchful heart of the team guarding against the fragility of humankind. Eve Myles (Doctor Who, Belonging) plays Gwen Cooper, initially an outsider whose first encounter with Torchwood sparks a burning curiosity to get to the truth and throws her into an unfamiliar but exciting world. Burn Gorman (Bleak House) plays the raw but charming medic, Owen Harper, and Naoko Mori (Absolutely Fabulous) is Toshiko Sato, the team member who specialises in all things technical. Torchwood is written by Russell T Davies and Chris Chibnall, with contributing writers including PJ Hammond,Toby Whithouse and Helen Raynor. A BBC production AF2 05 06 BBC 3 Final 18/7/06 14:02 Page 11 BODIES Tense, gripping, darkly humorous and scarily unsettling, the critically acclaimed Bodies, winner of the RTS Award for Best Drama Series, concludes with a 90-minute finale. Rob Lake’s (Max Beesley) life has changed beyond recognition since he fought to prevent patients coming to harm at the hands of his incompetent boss, Roger Hurley (Patrick Baladi). -

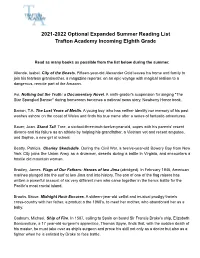

8Th Grade Optional Summer Reading Book List

2021-2022 Optional Expanded Summer Reading List Trafton Academy Incoming Eighth Grade Read as many books as possible from the list below during the summer. Allende, Isabel. City of the Beasts. Fifteen-year-old Alexander Cold leaves his home and family to join his fearless grandmother, a magazine reporter, on an epic voyage with magical realism to a dangerous, remote part of the Amazon. Avi. Nothing but the Truth: a Documentary Novel. A ninth-grader's suspension for singing "The Star Spangled Banner" during homeroom becomes a national news story. Newberry Honor book. Barron, T.A. The Lost Years of Merlin. A young boy who has neither identity nor memory of his past washes ashore on the coast of Wales and finds his true name after a series of fantastic adventures. Bauer, Joan. Stand Tall. Tree, a six-foot-three-inch-twelve-year-old, copes with his parents' recent divorce and his failure as an athlete by helping his grandfather, a Vietnam vet and recent amputee, and Sophie, a new girl at school. Beatty, Patricia. Charley Skedaddle. During the Civil War, a twelve-year-old Bowery Boy from New York City joins the Union Army as a drummer, deserts during a battle in Virginia, and encounters a hostile old mountain woman. Bradley, James. Flags of Our Fathers: Heroes of Iwo Jima (abridged). In February 1945, American marines plunged into the surf at Iwo Jima and into history. The son of one of the flag raisers has written a powerful account of six very different men who came together in the heroic battle for the Pacific's most crucial island. -

Comic Book Collection

2008 preview: fre comic book day 1 3x3 Eyes:Curse of the Gesu 1 76 1 76 4 76 2 76 3 Action Comics 694/40 Action Comics 687 Action Comics 4 Action Comics 7 Advent Rising: Rock the Planet 1 Aftertime: Warrior Nun Dei 1 Agents of Atlas 3 All-New X-Men 2 All-Star Superman 1 amaze ink peepshow 1 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Ame-Comi Girls 2 Ame-Comi Girls 3 Ame-Comi Girls 6 Ame-Comi Girls 8 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld 9 Angel and the Ape 1 Angel and the Ape 2 Ant 9 Arak, Son of Thunder 27 Arak, Son of Thunder 33 Arak, Son of Thunder 26 Arana 4 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 1 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 5 Archer & Armstrong 20 Archer & Armstrong 15 Aria 1 Aria 3 Aria 2 Arrow Anthology 1 Arrowsmith 4 Arrowsmith 3 Ascension 11 Ashen Victor 3 Astonish Comics (FCBD) Asylum 6 Asylum 5 Asylum 3 Asylum 11 Asylum 1 Athena Inc. The Beginning 1 Atlas 1 Atomic Toybox 1 Atomika 1 Atomika 3 Atomika 4 Atomika 2 Avengers Academy: Fear Itself 18 Avengers: Unplugged 6 Avengers: Unplugged 4 Azrael 4 Azrael 2 Azrael 2 Badrock and Company 3 Badrock and Company 4 Badrock and Company 5 Bastard Samurai 1 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 27 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 28 Batman:Shadow of the Bat 30 Big Bruisers 1 Bionicle 22 Bionicle 20 Black Terror 2 Blade of the Immortal 3 Blade of the Immortal unknown Bleeding Cool (FCBD) Bloodfire 9 bloodfire 9 Bloodshot 2 Bloodshot 4 Bloodshot 31 bloodshot 9 bloodshot 4 bloodshot 6 bloodshot 15 Brath 13 Brath 12 Brath 14 Brigade 13 Captain Marvel: Time Flies 4 Caravan Kidd 2 Caravan Kidd 1 Cat Claw 1 catfight 1 Children of -

Title Summary Review Between Shades of Gray Bluefish

Title Summary Review Sepetys’ first novel offers a harrowing and horrifying account of the forcible relocation of countless Lithuanians in the wake of the Russian invasion of their country in 1939. In the case of 15-year-old Lina, her mother, and her younger brother, this means deportation to a forced-labor camp in Siberia, where conditions are all too painfully similar to those of Nazi concentration camps. By Ruta Sepetys: In 1941, fifteen- Lina’s great hope is that somehow her father, who has already been arrested by the Soviet secret police, might find and rescue year-old Lina, her mother, and them. A gifted artist, she begins secretly creating pictures that can—she hopes—be surreptitiously sent to him in his own prison brother are pulled from their camp. Whether or not this will be possible, it is her art that will be her salvation, helping her to retain her identity, her dignity, Lithuanian home by Soviet guards and her increasingly tenuous hold on hope for the future. Many others are not so fortunate. Sepetys, the daughter of a Lithuanian and sent to Siberia. refugee, estimates that the Baltic States lost more than one-third of their populations during the Russian genocide. Though many continue to deny this happened, Sepetys’ beautifully written and deeply felt novel proves the reality is otherwise. Hers is an important book that deserves the widest possible readership. *William C. Morris Award Finalist *YALSA Top Ten Fiction Award Between Shades of Gray (Booklist) Historical Fiction 344 pages UG By Pat Schmatz: Thirteen-year-old Travis, living in cramped quarters Travis lives with his alcoholic grandfather and his beloved dog, Rosco. -

Exhibition Preview

Exhibition Preview Big blue skies, rugged canyons, loyal horses, damsels in distress, ruthless gunslingers, savage Indians and handsome but tormented men wearing cowboy hats. Yep, that just about describes the premise for many western films and televisions shows of Hollywood’s golden age. This exhibition peels back some of the history, mythology and popular culture layers to reveal the Western genre as ongoing narrative source for scholars, artists and film makers. The artworks, memorabilia, music and historical displays celebrate the nostalgia tied to the western genre and expose the facts and fiction about morality, race relations and economics in a complicated story that is the history of the American West. Featured Artists: Dick Ayers, Thomas Hart Benton, Charles Braden, Brose Brothers Productions, Anne Coe, Rita Consing, Dwayne Hall, Luis Alfonzo Jimenez, Richard Lillis, Lon Megargee, Ed Mell, Douglas Miles, Mark Newport, William Clinton Schenk and Fritz Scholder. Thank you: ASU Art Museum, ASU Center for Film and Popular Culture, Rolf Brown, Michael Collier Gallery, Michael Ging, Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, Phoenix Film Festival, Tempe History Museum and Dr. Larry and Holley Thompson. The following slides highlight some of the contemporary Arizona-based artists in the exhibition. Rita Consing, Phoenix Rita Consing The Lone Ranger and The Lone Ranger 2, 2017 acrylics on canvases Consing is a Philippine American artist. Her father was an artist and the family spent a lot of time traveling the world. She was exposed to a lot of different cultures and recalls being influenced images of Ninjas, Samurais and Bruce Lee in Asia while enjoying the American comic books and western reruns like “The Lone Ranger” in the West. -

Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Chris Yogerst University of Wisconsin - Washington County, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 18 Article 7 Issue 2 October 2014 10-1-2014 Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Chris Yogerst University of Wisconsin - Washington County, [email protected] Recommended Citation Yogerst, Chris (2014) "Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 18 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol18/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faith Under the Fedora: Indiana Jones and the Heroic Journey Towards God Abstract This essay explores how the original Indiana Jones trilogy (Raiders of the Lost Ark, Temple of Doom, and The Last Crusade) work as a single journey towards faith. In the first film, Indy fully rejects religion and by the third film he accepts God. How does this happen? Indy takes a journey by exploring archeology, mythology, and theology that is best exemplified by Joseph Campbell's The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Like many people who come to find faith, it does not occur overnight. Indy takes a similar path, using his career and adventurer status to help him find Ultimate Truth. Keywords Indiana Jones, Steven Spielberg, Hollywood, Faith, Radiers of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom Author Notes Chris Yogerst teaches film and communication courses for the University of Wisconsin Colleges and Concordia University Wisconsin. -

Beth Michael-Fox Thesis for Online

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER Present and Accounted For: Making Sense of Death and the Dead in Late Postmodern Culture Bethan Phyllis Michael-Fox ORCID: 0000-0002-9617-2565 Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. DECLARATION AND COPYRIGHT STATEMENT No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work. I confirm that no work previously submitted for credit has been reused verbatim. Any previously submitted work has been revised, developed and recontextualised relevant to the thesis. I confirm that no material of this thesis has been published in advance of its submission. I confirm that no third party proof-reading or editing has been used in this thesis. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Professor Alec Charles for his steadfast support and consistent interest in and enthusiasm for my research. I would also like to thank him for being so supportive of my taking maternity leave and for letting me follow him to different institutions. I would like to thank Professor Marcus Leaning for his guidance and the time he has dedicated to me since I have been registered at the University of Winchester. I would also like to thank the University of Winchester’s postgraduate research team and in particular Helen Jones for supporting my transfer process, registration and studies. -

Lettering to the Max the Art & History of Calligraphy

KORERO PRESS Lettering to the Max Ivan Castro, Alex Trochut Summary Lettering, the drawing, designing, and illustration of words, has a personal uniqueness that is increasingly valued in today's digital society, whether personal or professional. This manual, by the internationally renowned Iván Castro, outlines the basic materials and skills to get you started. Typographical concepts and the principles of construction and composition are decoded. In addition, Ivan outlines several practical projects that allow the reader, not just to practice, but to develop their own ideas. In-depth but accessible, this book is the ideal beginner's guide and an excellent reference for the more well versed. Korero Press 9781912740079 Pub Date: 3/1/21 Contributor Bio On Sale Date: 3/1/21 Ivan Castro is a graphic designer based in Barcelona, Spain, who specializes in calligraphy, lettering, and $32.95 USD typography. His work involves everything from advertising to editorial, and from packaging to logo design and Discount Code: LON gig posters. Although Ivan claims to have no specific style, one could say that he has a strong respect for the Trade Paperback history of popular culture. He has been working in the field for 20 years, and has been teaching calligraphy 128 Pages and lettering for 15 years in the main design schools in Barcelona. He travels frequently, holding workshops Full color throughout Carton Qty: 24 and giving lectures at design festivals and conferences. Alex Trochut was born in 1981 in Barcelona, Spain. Art / Techniques After completing his studies at Elisava Escola Superior de Disseny, Alex established his own design studio in ART003000 Barcelona before relocating to New York City.