The Past Is Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unimagined. Unexpected. Unexplored

Unimagined. Unexpected. Unexplored. OFFERING AN UNEXPECTED, OTHER- WORLDLY EXPERIENCE BOTH IN ITS LANDSCAPE AND THE REWARDS IT BRINGS TO TRAVELLERS, THE ARID EDEN ROUTE STRETCHES FROM SWAKOPMUND IN THE SOUTH TO THE ANGOLAN BORDER IN THE NORTH. THE ROUTE INCLUDES THE PREVIOUSLY RESTRICTED WESTERN AREA OF ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK, ONE OF NAMIBIA’S MOST IMPORTANT TOURIST DESTINATIONS WITH ALMOST ALL VISITORS TO THE COUNTRY INCLUDING THE PARK IN THEIR TRAVEL PLANS. The Arid Eden Route also includes well-known tourist attractions such as Spitzkoppe, Brandberg, Twyfelfontein and Epupa Falls. Travellers can experience the majesty of free-roaming animals, extreme landscapes, rich cultural heritage and breathtaking geological formations. As one of the last remaining wildernesses, the Arid Eden Route is remote yet accessible. DID YOU KNOW? TOP reasons to VISIT... “Epupa” is a Herero word for “foam”, in reference to the foam created by the falling water. Visit ancient riverbeds, In the Himba culture a sign of wealth is not the beauty or quality of a tombstone, craters and a petrified but rather the cattle you had owned during your lifetime, represented by the horns forest on your way to an on your grave. oasis in the desert – the Epupa Waterfall The desert-adapted elephants of the Kunene region rely on as little as nine species of plants for their survival while in Etosha they utilise over 80 species. At 2574m, Königstein is Namibia’s highest peak and is situated in the Brandberg Mountains. The Brandberg is home to over 1,000 San paintings, including the famous White Lady which dates back 2,000 years. -

Project Title: Environmental Impact Assessment for The

ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING REPORT (ESR): ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF A LODGE ESTABLISHMENT ON PORTION 150 ON THE REMAINDER OF THE FARM OUTJO TOWNLANDS NO. 193, OUTJO IN KUNENE REGION, NAMIBIA PROJECT TITLE: ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF A LODGE ESTABLISHMENT ON PORTION 150 ON THE REMAINDER OF THE FARM OUTJO TOWNLANDS NO. 193, OUTJO IN KUNENE REGION, NAMIBIA TITLE OF THE REPORT: ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING REPORT (ESR) ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF A LODGE ESTABLISHMENT ON PORTION 150 ON THE REMAINDER OF THE FARM OUTJO TOWNLANDS NO. 193, OUTJO IN KUNENE REGION, NAMIBIA. Compiled by : Proponent: Ritta Khiba Planning Consultants Farm House Bed and Breakfast and Restaurant P.O. Box 22543 Windhoek 1012 Virgo Street Doradopark (T&F)+26461225062|+264 88614935 (C) +26481 2505559 / 0815788154 (E) rkhiba@Outjo Municipalityail.com Environmental Assessment Practitioners Team : - Ritta Khiba PREPARED FOR: Office of the Environmental Commissioner, Ministry of Environment and Tourism SUBMIT COMMENTS AND QUERIES TO: 1012 Virgo Street, Dorado Park, Windhoek Tel: +264 61 225062 | Fax: +264 61 213158/088614935 Cell: +264 81 2505559 | Email: rkhiba@Outjo Municipalityail.com ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING REPORT (ESR): ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF A LODGE ESTABLISHMENT ON PORTION 150 ON THE REMAINDER OF THE FARM OUTJO TOWNLANDS NO. 193, OUTJO IN KUNENE REGION, NAMIBIA Contents 1. CHAPTER ONE: BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. -

The Main Vegetation Types of Kaokoland, Northern Damaraland and a Description of Some Transects of Owambo, Etosha and North Western South West Africa

THE MAIN VEGETATION TYPES OF KAOKOLAND, NORTHERN DAMARALAND AND A DESCRIPTION OF SOME TRANSECTS OF OWAMBO, ETOSHA AND NORTH WESTERN SOUTH WEST AFRICA Rui Ildegario de Sousa Correia June 1976 ~ € id Tdi MAIN VEGETATION TYPES OF KAOKOLAND, NORTHERN DAMARALAND AND A DESCRIPTION OF SOME TRANSECTS OF OWAMBO, ETOSHA AND NORTH WESTERN SOUT WEST AFRICA The general ecological conditions that influence the vege- tation types of the study area have already been described in a previous report. The main factor influencing vegetation here, is rainfall. Topography plays a very important paralel role related with an additional distribution of rainwater by the superficial drainage of hills and mountains to the neighbouring flats " and slopes. Concerning the soils, it appears that the physical structure is of more importance than the chemical composition, as this (the structure) determines the availability of water for root development. - Iu some specific instances the soil seems to have a marked effect on the vegetation such as the superficial calcareous layer in south-eastern Kaokoland. The influence of the watersheds is also well marked in deter- mining vegetation types, whether floristic or physiognomic. In addition both physiognomic features and floristic composi- tion have been used to determine the boundaries of the various vegetation types as described. Judicious use/..... ‘co Judicious use was also made of "indicator" species, whether by its occurence or by its absence. The following have been used-<« Baikeea plurijuga - Typical of red “alahari sands in the me~- dian and higher rainfall areas (300 - 700 mm/2),“- Spirostachys africane - Usually appears on the edge of pans (such as Owambo and Southern Angola) and along seasonal rockey c : or sandy dry water courses exept in the desert country courses. -

The De Beers and Namibia Partnership

DE BEERS AND NAMIBIA The partnership between the Government of the Republic of Namibia and De Beers delivers real and sustained benefits to Namibia and its people. ANNUAL CONTRIBUTION RESPONSIBLE FOR NAMIBIA RECEIVES MORE THAN TO STATE REVENUE MORE THAN 80 CENTS OVER 1 IN EVERY 5 DOLLARS OF EVERY OF NAMIBIA’S DOLLAR N$3bn FOREIGN EARNINGS GENERATED BY THE PARTNERSHIP SINGLE LARGEST CONTRIBUTOR INVESTMENT IN DEBMARINE NAMDEB HOLDINGS EMPLOYS AFTER GOVERNMENT VESSEL SS NUJOMA, APPROX. TO NAMIBIAN ECONOMY N$2.5bn 2,500 PLUS A MULTITUDE OF CONTRACTORS Cunene Okavango Ondangwa Oshakati Cuando Tsumeb Otavi Tsumkwe Kamanjab Grootfontein Outjo Khorixas Our recent partnership with the Otjiwarongo University of Namibia (UNAM) further Omaruru underscores our embodiment of true Usakos Okahandja partnerships. Many young Namibians Henties Bay NDTC Gobabis will now have the opportunity to Swakopmund WINDHOEK Walvis Bay attain tertiary education through this Rehoboth Aminuis programme. Aranos Stampriet Akanous And our new 10-year sales agreement, the longest ever agreed between Maltahohe Gochas Koes De Beers and the Government, DOUGLAS BAY Bethanien Keetmanshoop will see the partnership generate even Luderitz Aroab more value for the Namibian economy. ELIZABETH BAY Aus BOGENFELS MINING AREA 1 Grunau Karasburg SENDELINGSDRIF DABERAS ATLANTIC 1 AUCHAS Warmbad Oranjemund Orange DE BEERS/NAMIBIA 10-YEAR SALES AGREEMENT ANNOUNCED PARTNERSHIP TIMELINE MAY 2016 • US$430 million worth of rough diamonds offered annually to Namibia Diamond Trading Company customers -

TWYFELFONTEIN ADVENTURE CAMP • Facts 2019/2020 Nestled In

TWYFELFONTEIN ADVENTURE CAMP • Facts 2019/2020 Nestled in rolling boulders of a granite outcrop, Twyfelfontein Adventure Camp is conveniently situated a ten minute drive from Twyfelfontein Rock Engravings, within walking distance of the Damara Living Museum and within the Huab River Valley. A visit in the neighbouring Damara Living Museum can be done in own arrangement, it offers a fascinating look into the people, heritage, pulse and soul of Damaraland. Activity offered by TACamp: A scenic nature drive in the ephemeral Huab River and surrounding valley including a picnic lunch. It is an excursion exposing visitors to unique geological formations and the possibility of sighting the elusive desert- adapted elephants and rhinos. (Available during stays of two nights or more only) Two open game drive cars are permanently available with guides. That means 2 x 10 guests can do the activity. If bigger groups are booked in, the lodge can arrange a guide and a third car on request LOCATION D 3254 - 90km west of Khorixas 20°31'42.0"S 14°23'56.1"E Distance from • Windhoek 420km • Swakopmund 350km • Twyfelfontein 9km • Landing strip at Twyfelfontein, 5km ACCOMMODATION The camp consists of 12 furnished en-suite tents with two beds (twin room), an open bathroom with shower (hot and cold water), basin and toilet and a shaded terrace with armchairs. Tents are accessible by 3-4 steps and are not barrier free. 3 extra igloo tents are available, can be booked for tour guides if no normal tent is available or for children (to be built up next to their parents tent, sharing ablutions with parents) A baby cot is available and can be put in the parents tent. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Jerram Et Al Twyfelfontein Sandstone

Communs geol. Surv. Namibia, 12 (2000), 303-313 The Fossilised Desert: recent developments in our understanding of the Lower Cretaceous deposits in the Huab Basin, NW Namibia Dougal A. Jerram1, Nigel Mountney2, John Howell3 and Harald Stollhofen4 1Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Durham, South Rd, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK. (email [email protected]). 2School of Earth Sciences and Geography, Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK. 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 3BX, UK. 4Institut für Geologie, Universität Würzburg, 97070 Würzburg, Germany. The Lower Cretaceous deposits in the Huab Basin, NW Namibia, comprise fluvial and aeolian sandstones, lava flows and associated intrusions of the Etendeka Group. The sandstones formed part of a major aeolian sand sea (erg) system that was active across large tracts of the Paraná-Huab Basin during Lower Cretaceous times (133-132 Ma). This erg system was progressively engulfed and subsequently preserved beneath and between lava flows of the Paraná-Etendeka Flood Basalt Province. Burial of this erg by flood basalts has resulted in the preservation of a variety of intact aeolian bed forms. Preserved bed forms vary in type and scale from 1 km wavelength compound transverse draa to isolated barchan dunes with downwind wavelengths of < 100 m. Due to the present-day preferential erosion of the lava flows, preserved aeolian dunes are now exposed in 3-D in the position in which they were migrating ~133 Ma ago. A relatively non-de- structive eruption style of inflated pahoehoe flows preserved the bed form geomorphology. These first pahoehoe flow fields, comprising olivine-phyric Tafelkop lavas, define a shallow shield-like volcanic feature. -

Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and The

Elephant Volume 1 | Issue 4 Article 15 12-15-1980 Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and the Endangered Wildlife Trust: Kaokoland, South West Africa / Namibia Clive Walker Endangered Wildlife Trust of South Africa Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Walker, C. (1980). Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and the Endangered Wildlife Trust: Kaokoland, South West Africa / Namibia. Elephant, 1(4), 161-163. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521731752 This Brief Notes / Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Fall 1980 WALKER - EWT: KAOKOLAND 161 REPORT TO THE SURVIVAL SERVICE COMMISSION, IUCN AND THE ENDANGERED WILDLIFE TRUST: KAOKOLAND, SOUTH WEST AFRICA / NAMIBIA* by Clive Walker It is with the utmost urgency that I draw your attention to my recent visit to Kaokoland with Professor F.C. Eloff's expedition during September 1978, with the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Kaokoland is in the northwestern part of South West Africa/Namibia and covers an area of some 5½ million hectares (22,000 square miles) and at present is under the control of the South African Government and falls under the Minister of Plural Relations, Dr. C. Mulder. The most striking topographic feature of the region is the many mountains, from the dolomite hills in the south to the stark ridges and isolated eminences rising from the highland plains and to the towering peaks of the Northern Baynes and Otjihipa ranges. -

Discover Kaokoland Namibia Safari

Discover Kaokoland This guided safari offers you the perfect opportunity to experience Namibia's unspoilt North West. Away from the bustle of the normal tourist routes, you will encounter Namibia’s famous desert adapted elephants, the nomadic Ovahimbas, and the mighty Kunene river and its spectacular Epupa waterfalls. The tour ends with a final relaxing overnight at Palmwag Lodge (or similar) before returning back to Swakopmund via Twyfelfontein and its famous rock engravings. Day 1: Swakopmund / Damaraland Depart Swakopmund and travel along the Atlantic Coast towards the North. Visit the lichen fields near Wlotzka's Baken before continuing to Henties Bay, a small holiday resort. From Henties Bay, travel onward to the seal colony at Cape Cross. After visiting the seals, the journey continues via Ugabmund to the southern Skeleton Coast Park to inspect a shipwreck. We leave the Skeleton Coast Park in the early afternoon via Springbokwasser, allowing guests to experience the harsh transition from the Namib Desert to the Damaraland highlands with its impressive landscape and rugged valleys. Here you might be able to sight the first springbok, zebra and oryx and, with some luck, the desert elephants. Overnight stay in bungalows at Grootberg Lodge or similar. After enjoying a drink and a delicious supper, guests can luxuriate in the Lodge's cosy atmosphere and let the day's impressions sink in. Your Financial Protection All monies paid by you for the air holiday package shown [or flights if appropriate] are ATOL protected by the Civil Aviation Authority. Our ATOL number is ATOL 3145. For more information see our booking terms and conditions. -

Kunene Regional Development Profile 2015

Kunene Regional Council Kunene Regional Development Profile2015 The Ultimate Frontier Foreword 1 Foreword The Kunene Regional Devel- all regional stakeholders. These issues inhabitants and wildlife, but to areas opment Profile is one of the include, rural infrastructural develop- beyond our region, through exploring regional strategic documents ment, poverty and hunger, unemploy- and exposing everything Kunene has which profiles who we are as ment, especially youth, regional eco- to offer. the Great Kunene Region, what nomic growth, HIV/AIDS pandemic, I believe that if we rally together as a we can offer in terms of current domestic or gender based violence and team, the aspirations and ambitions of service delivery (strengths), our illegal poaching of our wildlife. our inhabitants outlined in this docu- regional economic perform- ment can be easily transformed into ances, opportunities, challenges It must be understood clearly to all of successful implementation of socio and and constraints. us as inhabitants of this Great Kunene, economic development in our region, and Namibians at large, that our re- which will guarantee job creation, In my personal capacity as the Region- gional vision has been aligned with our economic growth, peace and political al Governor of Kunene Region and a national vision. Taking into account stability. Regional Political Head Representative the current impact of development in of the government, I strongly believe our region, we have a lot that we need With these remarks, it is my honor and that the initiation -

Syllabuses History Feb2010.Pdf

Republic of Namibia MINISTRY OF EDUCATION JUNIOR SECONDARY PHASE HISTORY SYLLABUS GRADES 8 - 10 2010 Ministry of Education National Institute for Educational Development (NIED) Private Bag 2034 Okahandja Namibia © Copyright NIED, Ministry of Education, 2010 History Syllabus Grades 8 - 10 ISBN: 99916-48-22-4 Printed by NIED www.nied.edu.na Publication date: January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2. RATIONALE AND AIMS ................................................................................................... 1 3. BASIC COMPETENCIES AND LEARNING OUTCOMES ............................................. 1 5. GENDER ISSUES ................................................................................................................ 2 6. LOCAL CONTEXT AND CONTENT ................................................................................ 2 7. LINKS TO OTHER SUBJECTS AND CROSS-CURRICULAR ISSUES ......................... 2 8. APPROACH TO TEACHING AND LEARNING .............................................................. 7 9. SUMMARY OF LEARNING CONTENT .......................................................................... 8 10. LEARNING CONTENT ...................................................................................................... 9 10.1 LEARNING CONTENT FOR GRADE 8 ................................................................. 9 10.2 LEARNING CONTENT FOR GRADE 9 .............................................................. -

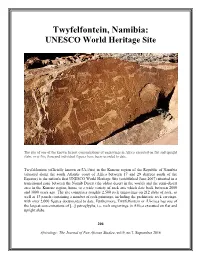

Twyfelfontein, Namibia: UNESCO World Heritage Site

Twyfelfontein, Namibia: UNESCO World Heritage Site The site of one of the known largest concentrations of engravings in Africa executed on flat and upright slabs; over five thousand individual figures have been recorded to date. Twyfelfontein (officially known as ǀUi-ǁAis) in the Kunene region of the Republic of Namibia (situated along the south Atlantic coast of Africa between 17 and 29 degrees south of the Equator) is the nation's first UNESCO World Heritage Site (established June 2007) situated in a transitional zone between the Namib Desert (the oldest desert in the world) and the semi-desert area in the Kunene region, home to a wide variety of rock arts which date back between 2000 and 3000 years ago. The site comprises roughly 2,500 rock engravings on 212 slabs of rock, as well as 13 panels containing a number of rock paintings, including the prehistoric rock carvings, with over 2,000 figures documented to date. Furthermore, Twyfelfontein or /Ui-//aes has one of the largest concentrations of [...] petroglyphs, i.e. rock engravings in Africa executed on flat and upright slabs. 206 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.9, no.7, September 2016 Most of these well-preserved engravings represent rhinoceros; the site also includes six paint elephant, ostrich and giraffe, as well as drawings of human and animal footprintsd rock shelters with motifs of human figures in red ochre. The objects excavated from two sections, date from the Late Stone Age. The site forms a coherent, extensive and high-quality record of ritual practices relating to hunter-gatherer communities in this part of southern Africa over at least 2,000 years, and eloquently illustrates the links between the ritual and economic practices of hunter-gatherers.