Framing Pfitzner, Strauss, Schreker, and Schoenberg Cinematically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei Conductor

SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Antonin Dvořák SympHONy NO.9, ‘FROm THE NEw wORlD’ Jean Sibelius FINlANDIA CHINEKE! ORCHESTRA Kevin John Edusei conductor 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD517_Bklt****.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 28/04/2017 16:19 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CyAN mAGENTA Customer yEllOw Catalogue No. BlACK Job Title page Nos. Jean Sibelius Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Finlandia Finlandia, Op 26 9’ Antonin Dvořák A brief trip to Finland is all that is required to grasp the legendary status that Jean Sibelius has acquired in his home nation. From his long-time home, Ainola, which has become a national Symphony No. 9, ‘From the New world’ museum, it is a mere 30 minute drive to Sibelius park in Helsinki, where sits the Sibelius monument. Budding Finnish musicians attend the Sibelius Academy, partake in the International Jean Sibelius Violin Competition and perform his symphonies in Sibelius Hall. Until the introduction of the euro, his portrait was on the Finnish 100 mark bill and Finland’s 1. Finlandia Jean Sibelius .....................................................................................................................................................[7.50] national Flag Day is now held on his birthday. But how did a musician and composer become a national hero, a position usually reserved for generals, freedom fighters and politicians? Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, Op. 95, ‘From the New World’ Antonin Dvořák 2. I. Adagio - Allegro molto ...............................................................................................................................................[11.42] e answer lies with Finlandia, Sibelius’ love letter to the Finnish nation. -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20Th Century Composers

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 1-8-2010 War on Modern Music and Music in Modern War: Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20th Century Composers David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. War on Modern Music and Music in Modern War: Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20th Century Composers. "Music, War, and Commemoration” Panel of the American Historical Association Conference in San Diego, CA, 2010, , : , 2010. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © 2010 David Dennis. WAR ON MODERN MUSIC AND MUSIC IN MODERN WAR: VÖLKISCHER BEOBACHTER RECEPTION OF 20th CENTURY COMPOSERS A paper for the “Music, War, and Commemoration” Panel of the American Historical Association Conference in San Diego, CA January 8, 2009 David B. Dennis Department of History Loyola University Chicago Recent scholarship on Nazi music policy pays little attention to the main party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, or comparable publications for the gen- eral public. Most work concentrates on publications Nazis targeted at expert audiences, in this case music journals. But to think our histories of Nazi music politics are complete without comprehensive analysis of the party daily is prema- ture. -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

Kevin John Crichton Phd Thesis

'PREPARING FOR GOVERNMENT?' : WILHELM FRICK AS THURINGIA'S NAZI MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR AND OF EDUCATION, 23 JANUARY 1930 - 1 APRIL 1931 Kevin John Crichton A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2002 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13816 This item is protected by original copyright “Preparing for Government?” Wilhelm Frick as Thuringia’s Nazi Minister of the Interior and of Education, 23 January 1930 - 1 April 1931 Submitted. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, 2001 by Kevin John Crichton BA(Wales), MA (Lancaster) Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP) Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) (c) 2001 KJ. Crichton ProQuest Number: 10170694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10170694 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author’. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 CONTENTS Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements Abbreviations Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Background 33 Chapter Three: Frick as Interior Minister I 85 Chapter Four: Frick as Interior Ministie II 124 Chapter Five: Frickas Education Miannsti^r' 200 Chapter Six: Frick a.s Coalition Minister 268 Chapter Seven: Conclusion 317 Appendix Bibliography 332. -

SWR2 Musikstunde Der Klang Der Moderne – Wien Um 1900 (1-5) Folge 5: Zwischenkriegszeit, Zweite Wiener Schule Und Zersprengung Von Andreas Maurer

SWR2 Musikstunde Der Klang der Moderne – Wien um 1900 (1-5) Folge 5: Zwischenkriegszeit, Zweite Wiener Schule und Zersprengung Von Andreas Maurer Sendung vom: 13. August 2021 Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2021 SWR2 können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören – oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Die SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen mindestens sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app Lange schwankte die Habsburger Monarchie zwischen Schönheit und Abgrund. Nun ist der Erste Weltkrieg vorbei. Die Monarchie ist Geschichte, die Republik wird ausgerufen. Doch was ist mit der Kunst passiert? Herzlich Willkommen zum 5. und letzten Teil unserer Musikstunde zur Wiener Moderne. Mein Name ist Andreas Maurer, schön, dass Sie wieder dabei sind. Wien 1918. Nichts ist nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg wie zuvor. Die Stadt ist erschüttert, Familien zerrissen. Das Jahr beginnt mit Streiks der Arbeiterbewegung. Unweit des Stephansdoms, in der Kärtnerstrasse, reißt ein wütender Mob den Doppeladler von den Wänden der Hoflieferanten. Hunger und Unterernährung, extremer Mangel, Kälte, Krankheiten und Epidemien wie die Spanische Grippe oder die Tuberkulose fordern viele Tote. Vier Hauptprotagonisten der Wiener Moderne - Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Otto Wagner und Kolo Moser – sterben noch im selben Jahr. -

Honorary Members, Rings of Honour, the Nicolai Medal and the “Yellow” List)

Oliver Rathkolb Honours and Awards (Honorary Members, Rings of Honour, the Nicolai Medal and the “Yellow” List) A compilation of the bearers of rings of honour was produced in preparation for the Vienna Philharmonic's centennial celebrations.1 It can not currently be reconstructed when exactly the first rings were awarded. In the archive of the Vienna Philharmonic, there are clues to a ring from 19282, and it follows from an undated index “Ehrenmitglieder, Träger des Ehrenrings, Nicolai Medaillen“3 that the second ring bearer, the Kammersänger Richard Mayr, had received the ring in 1929. Below the list of the first ring bearers: (Dates of the bestowal are not explicitly noted in the original) Dr. Felix von Weingartner (honorary member) Richard Mayr (Kammersänger, honorary member) Staatsrat Dr. Wilhelm Furtwängler (honorary member) Medizinalrat Dr. Josef Neubauer (honorary member) Lotte Lehmann (Kammersängerin) Elisabeth Schumann (Kammersängerin) Generalmusikdirektor Prof. Hans Knappertsbusch (March 12, 1938 on the occasion of his 50th birthday) In the Nazi era, for the first time (apart from Medizinalrat Dr. Josef Neubauer) not only artists were distinguished, but also Gen. Feldmarschall Wilhelm List (unclear when the ring was presented), Baldur von Schirach (March 30, 1942), Dr. Arthur Seyß-Inquart (March 30, 1942). 1 Archive of the Vienna Philharmonic, Depot State Opera, folder on the centennial celebrations 1942, list of the honorary members. 2 Information Dr. Silvia Kargl, AdWPh 3 This undated booklet was discovered in the Archive of the Vienna Philharmonic during its investigation by Dr. Silvia Kargl for possibly new documents for this project in February 2013. 1 Especially the presentation of the ring to Schirach in the context of the centennial celebration was openly propagated in the newspapers. -

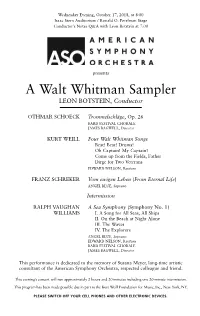

A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Wednesday Evening, October 17, 2018, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium / Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents A Walt Whitman Sampler LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor OTHMAR SCHOECK Trommelschläge, Op. 26 BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director KURT WEILL Four Walt Whitman Songs Beat! Beat! Drums! Oh Captain! My Captain! Come up from the Fields, Father Dirge for Two Veterans EDWARD NELSON, Baritone FRANZ SCHREKER Vom ewigen Leben (From Eternal Life) ANGEL BLUE, Soprano Intermission RALPH VAUGHAN A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1) WILLIAMS I. A Song for All Seas, All Ships II. On the Beach at Night Alone III. The Waves IV. The Explorers ANGEL BLUE, Soprano EDWARD NELSON, Baritone BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This performance is dedicated to the memory of Susana Meyer, long-time artistic consultant of the American Symphony Orchestra, respected colleague and friend. This evening’s concert will run approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. This program has been made possible due in part to the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc., New York, NY. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director Whitman and Democracy comprehend the English of Shakespeare by Leon Botstein or even Jane Austen without some reflection. (Indeed, even the space Among the most arguably difficult of between one generation and the next literary enterprises is the art of transla- can be daunting.) But this is because tion. Vladimir Nabokov was obsessed language is a living thing. There is a about the matter; his complicated and decided family resemblance over time controversial views on the processes of within a language, but the differences transferring the sensibilities evoked by in usage and meaning and in rhetoric one language to another have them- and significance are always developing. -

Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Michael James Schmidt 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany Committee: David F. Crew, Supervisor Judith Coffin Sabine Hake Tracie Matysik Karl H. Miller The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany by Michael James Schmidt, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 To my family: Mom, Dad, Paul, and Lindsey Acknowledgements I would like to thank, above all, my advisor David Crew for his intellectual guidance, his encouragement, and his personal support throughout the long, rewarding process that culminated in this dissertation. It has been an immense privilege to study under David and his thoughtful, open, and rigorous approach has fundamentally shaped the way I think about history. I would also like to Judith Coffin, who has been patiently mentored me since I was a hapless undergraduate. Judy’s ideas and suggestions have constantly opened up new ways of thinking for me and her elegance as a writer will be something to which I will always aspire. I would like to express my appreciation to Karl Hagstrom Miller, who has poignantly altered the way I listen to and encounter music since the first time he shared the recordings of Ellington’s Blanton-Webster band with me when I was 20 years old. -

Musicians Who Kept It Quiet During World War II

Musicians who kept it quiet during World War II • Shirley Apthorp From: The Australian November 19, 2011 12:00AM The Spivakovsky-Kurtz trio, from left, Tossy and Jascha Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz. Source: Supplied German musicologist and music critic Albrecht Dumling. Picture: Ana Pinto Source: Supplied THE invitation to bomb Berlin caught Albrecht Dumling by surprise. The German musicologist was not being collared by militant extremists in a dark pub. He was visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. There is an exhibit of a Royal Air Force bomber plane with an interactive button to simulate bombing Berlin. "It's like an adventure toy," Dumling recalls. "It felt very strange to be prompted to drop bombs on Berlin. I didn't." Instead, he wrote a book. Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia has just been published by the Bohlau Verlag in Germany. It contains many shocking revelations about a largely forgotten side of Australia's cultural past. Questioning the way history is presented is one of Dumling's chief preoccupations. He was in Canberra to sift through the National Archives, looking into what really happened to Jewish musicians whose flight from Nazi terror brought them to Australia. Today, it is tempting to imagine Australia as a safe haven, where the unjustly persecuted could begin again. The reality was different. Australia was not eager to accept Jewish immigrants. At the Evian Conference of 1938, Australia's trade and customs minister Thomas White, pleading against large-scale Jewish immigration, declared that "as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one". -

Musikalien Aus Dem Schönberg-Nachlaß / Printed Music from Schönberg’S Legacy

Musikalien aus dem Schönberg-Nachlaß / Printed music from Schönberg’s legacy 1. "110 Wiener Lieder Und Tänze."[Wiener Lieder Und Tänze], ed.//ed.//Vorwort Carl Michael Ziehrer, Rudolf Kronegger, and Vincenz Chiavacci. Wiener Musik, Leipzig: Lyra-Verlag, [19--?]. Notes: 'Enthaltend: Schätze der Wiener Volksmusik aus alter und neuer Zeit weiters Kompositionen von Ascher, Eysler, Fall, Lehar, Reinhardt, Stolz, Strauss und Behrer.'--t.p. Songs for voice and piano ; dances for piano solo. Introduction p. [3-4]: Die Wiener Volksmusik / von Vincenz Chiavacci. Includes index. Annotation on p. 49. 2. "Der Kanon: Ein Singbuch Für Alle."[Der Kanon], ed.//Forward Fritz Jode, and Herman Reichenbach. 9.-10. Tausend der Gesamtausg., verb. Aufl ed. Freiheit Und Heil, Wolfenbüttel: Georg Kallmeyer Verlag, 1932. Notes: Forward by Hermann Reichenbach ; afterword by Fritz Jode. Contains canons by many different composers, for 2 to 10 voices, both sacred and secular. Includes indexes. Includes indexes. Annotation on p. 353 3. "Excelsior: 100 Musikalische Erfolge."[Excelsior], Wien: Universal-Edition, [19--?]. Notes: Each volume contains 'Ernste Musik' and 'Heitere Musik' by various composers, written for or arranged for either voice and piano or piano alone. Certain pieces underlined in table of contents in each vol. Correction of accidental in v. 2 on p. 200. Volume numbers written in pen on covers. 4. "Opera Overtures." Hampton Miniature Arrow Scores, v. 10. New York: E. B. Marks Music Corp., 1943. Notes: Four miniature score pages reproduced on each page (i.e. 361 p. reproduced on 96 p.) Contents: Mignon / Thomas -- Merry wives of Windsor / Nicolai -- Hansel and Gretel / Humperdinck -- Russlan and Ludmilla / Glinka -- The bartered bride / Smetana -- Die Fledermaus ; The gipsy baron / Strauss.