Memory Distortion and Source Amnesia – a Review of Why Our Memories Can Be Badly Mistaken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Rehabilitation of Prospective Memory Deficits After Acquired Brain Injury: Cognitive, Behavioral, and Physiological Measures

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Cognitive Rehabilitation of Prospective Memory Deficits after Acquired Brain Injury: Cognitive, Behavioral, and Physiological Measures Meaghan Race [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Behavioral Neurobiology Commons, Cognitive Neuroscience Commons, and the Computational Neuroscience Commons Recommended Citation Race, Meaghan, "Cognitive Rehabilitation of Prospective Memory Deficits after Acquired Brain Injury: Cognitive, Behavioral, and Physiological Measures". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2019. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/757 TRINITY COLLEGE COGNITIVE REHABILITATION OF PROSPECTIVE MEMORY DEFICITS AFTER ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY: COGNITIVE, BEHAVIORAL, AND PHYSIOLOGICAL MEASURES BY Meaghan Race A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE NEUROSCIENCE PROGRAM IN CANDIDACY FOR THE MASTER’S OF ARTS DEGREE IN NEUROSCIENCE NEUROSCIENCE PROGRAM HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT May 9th, 2019 2 COGNITIVE REHABILITATION FOR PROSPECTIVE MEMORY Cognitive rehabiLitation of prospective memory deficits after acquired brain injury: cognitive, behavioraL, and physiologicaL measures BY Meaghan Race Master’s Thesis Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Sarah Raskin, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________________________ Dan LLoyd, Thesis Committee -

Assessment of Confabulation in Patients RENSON Publishedonline11sepetember2015 GREEN

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/13854046.2015.1084377 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Renson, Y. C. M., Oosterman, J. M., van Damme, J. E., Griekspoor, S. I. A., Wester, A. J., Kopelman, M. D., & Kessels, R. P. C. (2015). Assessment of Confabulation in Patients with Alcohol-Related Cognitive Disorders: The Nijmegen–Venray Confabulation List (NVCL-20). The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29, 804-823. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1084377 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Compare and Contrast Two Models Or Theories of One Cognitive Process with Reference to Research Studies

! The following sample is for the learning objective: Compare and contrast two models or theories of one cognitive process with reference to research studies. What is the question asking for? * A clear outline of two models of one cognitive process. The cognitive process may be memory, perception, decision-making, language or thinking. * Research is used to support the models as described. The research does not need to be outlined in a lot of detail, but underatanding of the role of research in supporting the models should be apparent.. * Both similarities and differences of the two models should be clearly outlined. Sample response The theory of memory is studied scientifically and several models have been developed to help The cognitive process describe and potentially explain how memory works. Two models that attempt to describe how (memory) and two models are memory works are the Multi-Store Model of Memory, developed by Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968), clearly identified. and the Working Memory Model of Memory, developed by Baddeley & Hitch (1974). The Multi-store model model explains that all memory is taken in through our senses; this is called sensory input. This information is enters our sensory memory, where if it is attended to, it will pass to short-term memory. If not attention is paid to it, it is displaced. Short-term memory Research. is limited in duration and capacity. According to Miller, STM can hold only 7 plus or minus 2 pieces of information. Short-term memory memory lasts for six to twelve seconds. When information in the short-term memory is rehearsed, it enters the long-term memory store in a process called “encoding.” When we recall information, it is retrieved from LTM and moved A satisfactory description of back into STM. -

Probing Echoic Memory with Different Voices

Memory & Cognition 1977, Vol. 5 (3),331-334 Probing echoic memory with different voices DAVID J. MADDEN and JARVIS BASTIAN University ofCalifornia, Davis, California 95616 Considerable evidence has indicated that some acoustical properties of spoken items are preserved in an "echoic" memory for approximately 2 sec. However, some of this evidence has also shown that changing the voice speaking the stimulus items has a disruptive effect on memory which persists longer than that of other acoustical variables. The present experiment examined the effect of voice changes on response bias as well as on accuracy in a recognition memory task. The task involved judging recognition probes as being present in or absent from sets of dichotically presented digits. Recognition of probes spoken in the same voice as that of the dichotic items was more accurate than recognition of different-voice probes at each of three retention intervals of up to 4 sec. Different-voice probes increased the likelihood of "absent" responses, but only up to a l.4-sec delay. These shifts in response bias may represent a property of echoic memory which should be investigated further. The concept of an "echoic" memory was first devel pairs of spoken consonants or vowels in a timed same/ oped by Neisser (1967), who proposed that a listener different recognition test. The items of a pair could be possesses a fairly literal but rapidly fading representation spoken in either the same voice or different voices, a of recent auditory events. Research motivated by this variable which was not relevant to the subjects' deci concept suggests that the exact time course of such sions. -

Episodic Memory in Transient Global Amnesia: Encoding, Storage, Or Retrieval Deficit?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.148 on 1 February 1999. Downloaded from 148 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:148–154 Episodic memory in transient global amnesia: encoding, storage, or retrieval deficit? Francis Eustache, Béatrice Desgranges, Peggy Laville, Bérengère Guillery, Catherine Lalevée, Stéphane SchaeVer, Vincent de la Sayette, Serge Iglesias, Jean-Claude Baron, Fausto Viader Abstract evertheless this division into processing stages Objectives—To assess episodic memory continues to be useful in helping understand (especially anterograde amnesia) during the working of memory systems”. These three the acute phase of transient global amne- stages may be defined in the following way: (1) sia to diVerentiate an encoding, a storage, encoding, during which perceptive information or a retrieval deficit. is transformed into more or less stable mental Methods—In three patients, whose am- representations; (2) storage (or consolidation), nestic episode fulfilled all current criteria during which mnemonic information is associ- for transient global amnesia, a neuro- ated with other representations and maintained psychological protocol was administered in long term memory; (3) retrieval, during which included a word learning task which the subject can momentarily reactivate derived from the Grober and Buschke’s mnemonic representations. These definitions procedure. will be used in the present study. Results—In one patient, the results sug- Regarding the retrograde amnesia of TGA, it gested an encoding deficit, -

Reducing False Memories Chad S

MacLeod and MacDonald – The Stroop effect and attention Review 17 Dunbar, K.N. and MacLeod, C.M. (1984) A horse race of a different 28 Carter, C.S. et al. (2000) Parsing executive processes: strategic versus color: Stroop interference patterns with transformed words. J. Exp. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 10, 622–639 Sci. U. S. A. 97, 1944–1948 18 Fraisse, P. (1969) Why is naming longer than reading? Acta Psychol. 29 Derbyshire, S.W.G. et al. (1998) Pain and Stroop interference activate 30, 96–103 separate processing modules in anterior cingulate. Exp. Brain Res. 19 Kolers, P.A. (1975) Memorial consequences of automatized encoding. 118, 52–60 J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 1, 689–701 30 Bush, G. et al. (2000) Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior 20 Tzelgov, J. et al. (1992) Controlling Stroop effects by manipulating cingulate cortex. Trends Cognit. Sci. 4, 215–222 expectations for color words. Mem. Cognit. 20, 727–735 31 Corbetta, M. et al. (1991) Selective and divided attention during visual 21 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. (1981) P300 latency: a new metric of discriminations of shape, color, and speed: functional anatomy by information processing. Psychophysiology 18, 207–215 positron emission tomography. J. Neurosci. 11, 2383–2402 22 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. and Kopell, B.S. (1981) The Stroop effect: brain 32 Petersen, S.E. et al. (1988) Positron emission tomographic studies potentials localize the source of interference. Science 214, 938–940 of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature 23 Bench, C.J. -

Iconic Memory and Visible Persistence

Perception & Psychophysics 1980, Vol. 27 (3),183-228 Iconic memory and visible persistence MAX COLTHEART Birkbeck College, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HX, England There are three senses in which a visual stimulus may be said to persist psychologically for some time after its physical offset. First, neural activity in the visual system evoked by the stimulus may continue after stimulus offset ("neural persistence"). Second, the stimulus may continue to be visible for some time after its offset ("visible persistence"). Finally, information about visual properties of the stimulus may continue to be available to an observer for some time after stimulus offset ("informational persistence"). These three forms of visual persistence are widely assumed to reflect a single underlying process: a decaying visual trace that (1) con sists of afteractivity in the visual system, (2) is visible, and (3) is the source of visual informa tion in experiments on decaying visual memory. It is argued here that this assumption is incor rect. Studies of visible persistence are reviewed; seven different techniques that have been used for investigating visible persistence are identified, and it is pointed out that numerous studies using a variety of techniques have demonstrated two fundamental properties of visible per sistence: the inverse duration effect (the longer a stimulus lasts, the shorter is its persistence after stimulus offset) and the inverse intensity effect (the more intense the stimulus, the briefer its persistence). Only when stimuli are so intense as to produce afterimages do these two effects fail to occur. Work on neural persistences is briefly reviewed; such persistences exist at the photoreceptor level and at various stages in the visual pathways. -

Memory Specificity, but Not Perceptual Load, Affects Susceptibility to Misleading Information

Memory specificity, but not perceptual load, affects susceptibility to misleading information Francesca R. Farina1,2,* & Ciara M. Greene1 1School of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland. 2Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Note: This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed. Please contact the authors before citing. Correspondence may be sent to Francesca Farina, Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine the role of perceptual load in eyewitness memory accuracy and susceptibility to misinformation at immediate and delayed recall. Despite its relevance to real-world situations, previous research in this area is limited. A secondary aim was to establish whether trait-based memory specificity can protect against susceptibility to misinformation. Participants (n=264) viewed a 1-minute video depicting a crime and completed a memory questionnaire immediately afterwards and one week later. Memory specificity was measured via an online version of the Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT). We found a strong misinformation effect, but no effect of perceptual load on memory accuracy or suggestibility at either timepoint. Memory specificity was a significant predictor of accuracy for both neutrally phrased and leading questions, though the effect was weaker after a one-week delay. Results suggest that specific autobiographical memory, but not perceptual load, enhances eyewitness memory and protects against misinformation. Keywords Perceptual load; memory specificity; eyewitness; misinformation. 2 General Audience Summary The misinformation effect is a memory impairment for a past event that occurs when a person is presented with leading information. Leading information can distort the original details of a memory and produce false memories. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

Memory Stores Iconic Memory Decays Very Quickly, and This Explains Why

In the late 60's, serial position curves (Murdock, 1962) were used as evidence to support the MSM. Primacy efects were considered evidence of rehearsal and so long-term storage whereas recency efects were considered evidence of the short-term memory store. The serial position curve was shown to occur regardless of list length and recency was removed if there was a delay between rehearsal The initial approach was the information We will see why this is and recall. Evidence for the MSM processing approach which suggests that not the case sensory processes pass through several stores: throughout the Namely, the sensory memory store, the short- lectures. However, recency efects were demonstrated over term and then the long-term memory store. long time intervals by Baddeley et al. (1977). Recency is not reflect STM but a more general accessibility to more recent experiences. Memory Stores If short-term memory is post-categorical (as suggested by Neath and Merikle) then it requires information (category membership of letters) from long-term memory = There must be communication. Short-Term Memory Multi-Store Model (Atkinson & Shifrin, 1968) VS. Working Memory Short term is a simple store, whereas working memory is a 'mental workspace. STM is a part of working memory. Working memory allows manipulation to allow reasoning, learning and comprehension. It has a limited capacity, temporary store and has a speech like or phonological code (subvocal). Sensory Memory Baddeley (1966) Phonological Similarity: asked The Sufx Efect where a sufx (e.g spoken word Free Recall Studies where participants can participants to perform serial recall of 4 types of Visual Iconic Memory (Sperling, 1960) Purely at the end of the remembered list) drastically choose to recall from any part of the list. -

Functional–Anatomic Correlates of Control Processes in Memory

The Journal of Neuroscience, May 15, 2003 • 23(10):3999–4004 • 3999 Functional–Anatomic Correlates of Control Processes in Memory Randy L. Buckner Department of Psychology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130 Introduction when memory retrieval requires flexible use of control processes A central role for control processes in long-term memory is ap- (Milner et al., 1985; Schacter, 1987; Shimmamura et al., 1991). In parent when one considers that there is far more information many cases, patients will fail to recall, or sometimes even recog- available in memory than can be accessed at any single moment nize, information (for review, see Wheeler et al., 1995) or inap- (Tulving and Pearlstone, 1966; Koriat, 2000). Much as selective propriately estimate the source or timing, or both, of a past epi- attention operates to focus processing on objects in the environ- sode (for review, see Schacter, 1987). In rare cases, a patient may ment, related control processes are required to constrain and make up episodes from the past while believing they really hap- select from information stored in memory. pened, a phenomenon called “confabulation” (Moscovitch, Neuroimaging studies have expanded our understanding of 1989; Burgess and Shallice, 1996). Unlike purer forms of amnesia, control processes in long-term memory in three important ways. which result from medial temporal and diencephalic lesions First, networks of regions, prominently including specific regions (Scoville and Milner, 1957; Squire, 1992; Cohen and Eichen- in prefrontal cortex, contribute to control processes during baum, 1993), the deficits after frontal damage align more to im- memory retrieval. -

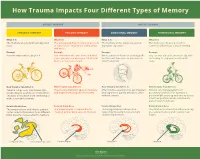

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory.