THE UNIFIED PROCESS in a to Questions Called up by the Machine on Its View- NUTSHELL Ing Screen, and Receives a Sum of Cash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing and Reviewing Use-Case Descriptions

Bittner/Spence_06.fm Page 145 Tuesday, July 30, 2002 12:04 PM PART II WRITING AND REVIEWING USE-CASE DESCRIPTIONS Part I, Getting Started with Use-Case Modeling, introduced the basic con- cepts of use-case modeling, including defining the basic concepts and understanding how to use these concepts to define the vision, find actors and use cases, and to define the basic concepts the system will use. If we go no further, we have an overview of what the system will do, an under- standing of the stakeholders of the system, and an understanding of the ways the system provides value to those stakeholders. What we do not have, if we stop at this point, is an understanding of exactly what the system does. In short, we lack the details needed to actually develop and test the system. Some people, having only come this far, wonder what use-case model- ing is all about and question its value. If one only comes this far with use- case modeling, we are forced to agree; the real value of use-case modeling comes from the descriptions of the interactions of the actors and the system, and from the descriptions of what the system does in response to the actions of the actors. Surprisingly, and disappointingly, many teams stop after developing little more than simple outlines for their use cases and consider themselves done. These same teams encounter problems because their use cases are vague and lack detail, so they blame the use-case approach for having let them down. The failing in these cases is not with the approach, but with its application. -

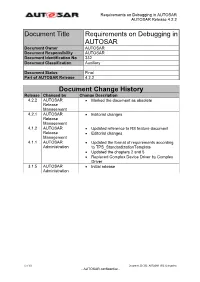

Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR

Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Title Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 332 Document Classification Auxiliary Document Status Final Part of AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Document Change History Release Changed by Change Description 4.2.2 AUTOSAR Marked the document as obsolete Release Management 4.2.1 AUTOSAR Editorial changes Release Management 4.1.2 AUTOSAR Updated reference to RS feature document Release Editorial changes Management 4.1.1 AUTOSAR Updated the format of requirements according Administration to TPS_StandardizationTemplate Updated the chapters 2 and 5 Replaced Complex Device Driver by Complex Driver 3.1.5 AUTOSAR Initial release Administration 1 of 19 Document ID 332: AUTOSAR_SRS_Debugging - AUTOSAR confidential - Requirements on Debugging in AUTOSAR AUTOSAR Release 4.2.2 Disclaimer This specification and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR, is for the purpose of information only. AUTOSAR and the companies that have contributed to it shall not be liable for any use of the specification. The material contained in this specification is protected by copyright and other types of Intellectual Property Rights. The commercial exploitation of the material contained in this specification requires a license to such Intellectual Property Rights. This specification may be utilized or reproduced without any modification, in any form or by any means, for informational purposes only. For any other purpose, no part of the specification may be utilized or reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. The AUTOSAR specifications have been developed for automotive applications only. -

Using the UML for Architectural Description?

Using the UML for Architectural Description? Rich Hilliard Integrated Systems and Internet Solutions, Inc. Concord, MA USA [email protected] Abstract. There is much interest in using the Unified Modeling Lan- guage (UML) for architectural description { those techniques by which architects sketch, capture, model, document and analyze architectural knowledge and decisions about software-intensive systems. IEEE P1471, the Recommended Practice for Architectural Description, represents an emerging consensus for specifying the content of an architectural descrip- tion for a software-intensive system. Like the UML, IEEE P1471 does not prescribe a particular architectural method or life cycle, but may be used within a variety of such processes. In this paper, I provide an overview of IEEE P1471, describe its conceptual framework, and investigate the issues of applying the UML to meet the requirements of IEEE P1471. Keywords: IEEE P1471, architectural description, multiple views, view- points, Unified Modeling Language 1 Introduction The Unified Modeling Language (UML) is rapidly maturing into the de facto standard for modeling of software-intensive systems. Standardized by the Object Management Group (OMG) in November 1997, it is being adopted by many organizations, and being supported by numerous tool vendors. At present, there is much interest in using the UML for architectural descrip- tion: the techniques by which architects sketch, capture, model, document and analyze architectural knowledge and decisions about software-intensive systems. Such techniques enable architects to record what they are doing, modify or ma- nipulate candidate architectures, reuse portions of existing architectures, and communicate architectural information to others. These descriptions may the be used to analyze and reason about the architecture { possibly with automated support. -

The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases

USE-CASE 2.0 The Guide to Succeeding with Use Cases Ivar Jacobson Ian Spence Kurt Bittner December 2011 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide About this Guide 3 How to read this Guide 3 What is Use-Case 2.0? 4 First Principles 5 Principle 1: Keep it simple by telling stories 5 Principle 2: Understand the big picture 5 Principle 3: Focus on value 7 Principle 4: Build the system in slices 8 Principle 5: Deliver the system in increments 10 Principle 6: Adapt to meet the team’s needs 11 Use-Case 2.0 Content 13 Things to Work With 13 Work Products 18 Things to do 23 Using Use-Case 2.0 30 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all types of system 30 Use-Case 2.0: Handling all types of requirement 31 Use-Case 2.0: Applicable for all development approaches 31 Use-Case 2.0: Scaling to meet your needs – scaling in, scaling out and scaling up 39 Conclusion 40 Appendix 1: Work Products 41 Supporting Information 42 Test Case 44 Use-Case Model 46 Use-Case Narrative 47 Use-Case Realization 49 Glossary of Terms 51 Acknowledgements 52 General 52 People 52 Bibliography 53 About the Authors 54 USE-CASE 2.0 The Definitive Guide Page 2 © 2005-2011 IvAr JacobSon InternationAl SA. All rights reserved. About this Guide This guide describes how to apply use cases in an agile and scalable fashion. It builds on the current state of the art to present an evolution of the use-case technique that we call Use-Case 2.0. -

INCOSE: the FAR Approach “Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations”

in Proceedings of the 16th Intern. Symposium of the International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE'06), Orlando, FL, USA, Jul 2006. The FAR Approach – Functional Analysis/Allocation and Requirements Flowdown Using Use Case Realizations Magnus Eriksson1,2, Kjell Borg1, Jürgen Börstler2 1BAE Systems Hägglunds AB 2Umeå University SE-891 82 Örnsköldsvik SE-901 87 Umeå Sweden Sweden {magnus.eriksson, kjell.borg}@baesystems.se {magnuse, jubo}@cs.umu.se Copyright © 2006 by Magnus Eriksson, Kjell Borg and Jürgen Börstler. Published and used by INCOSE with permission. Abstract. This paper describes a use case driven approach for functional analysis/allocation and requirements flowdown. The approach utilizes use cases and use case realizations for functional architecture modeling, which in turn form the basis for design synthesis and requirements flowdown. We refer to this approach as the FAR (Functional Architecture by use case Realizations) approach. The FAR approach is currently applied in several large-scale defense projects within BAE Systems Hägglunds AB and the experience so far is quite positive. The approach is illustrated throughout the paper using the well known Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) example. INTRODUCTION Organizations developing software intensive defense systems, for example vehicles, are today faced with a number of challenges. These challenges are related to the characteristics of both the market place and the system domain. • Systems are growing ever more complex, consisting of tightly integrated mechanical, electrical/electronic and software components. • Systems have very long life spans, typically 30 years or longer. • Due to reduced acquisition budgets, these systems are often developed in relatively short series; ranging from only a few to several hundred units. -

Challenges and Opportunities for the Medical Device Industry Meeting the New IEC 62304 Standard 2 Challenges and Opportunities for the Medical Device Industry

IBM Software Thought Leadership White Paper Life Sciences Challenges and opportunities for the medical device industry Meeting the new IEC 62304 standard 2 Challenges and opportunities for the medical device industry Contents With IEC 62304, the world has changed—country by country— for medical device manufacturers. This doesn’t mean, however, 2 Executive summary that complying with IEC 62304 must slow down your medical 2 Changes in the medical device field device software development. By applying best practices guid- ance and process automation, companies have a new opportunity 3 What is so hard about software? to improve on their fundamental business goals, while getting through regulatory approvals faster, lowering costs and deliver- 4 Disciplined agile delivery: Flexibility with more structure ing safer devices. 4 Meeting the specification: A look at some of the details This paper will explore what IEC 62304 compliance means for manufacturers in some detail, and also describe the larger con- text of systems and software engineering best practices at work 6 Process steps for IEC 62304 compliance in many of today’s most successful companies. 7 Performing the gap analysis Changes in the medical device field 8 Choosing software tools for IEC 62304 The IEC 62304 standard points to the more powerful role that software plays in the medical device industry. Once hardware 11 Conclusion was king. Older systems used software, of course, but it was not the main focus, and there wasn’t much of a user interface. Executive summary Software was primarily used for algorithmic work. Not to overly The recent IEC 62304 standard for medical device software is generalize, but the focus of management was on building causing companies worldwide to step back and examine their hardware that worked correctly; software was just a necessary software development processes with considerable scrutiny. -

UML : Introduction

UML : introduction Achref El Mouelhi Docteur de l’universite´ d’Aix-Marseille Chercheur en programmation par contrainte (IA) Ingenieur´ en genie´ logiciel [email protected] H & H: Research and Training 1 / 16 UML : introduction Achref El Mouelhi Docteur de l’universite´ d’Aix-Marseille Chercheur en programmation par contrainte (IA) Ingenieur´ en genie´ logiciel [email protected] H & H: Research and Training 2 / 16 UML © Achref EL MOUELHI © Pour construire cette maison Il faut etablir´ un plan avant H & H: Research and Training 3 / 16 UML La realisation´ d’une application peut passer par plusieurs etapes´ Definition´ des besoins Analyse Conception Developpement´ Test Validation© Achref EL MOUELHI © Deploiement´ Maintenance ... H & H: Research and Training 4 / 16 UML Ou` est UML dans tout c¸a ? UML permet de modeliser´ toutes les etapes´ du developpement´ d’une application de l’analyse au deploiement´ (en utilisant plusieurs diagrammes). © Achref EL MOUELHI © H & H: Research and Training 5 / 16 UML UML : Unified Modeling Language Un langage de modelisation´ unifie´ Ce n’est pas un langage de programmation Independant´ de tout langage de programmation (objet ou autre) Un langage base´ sur des notations graphiques Constitues´ de plusieurs graphes (diagrammes) permettant de visualiser© la Achref future application EL MOUELHI de plusieurs angles © differents´ Une norme maintenue par l’OMG (Object Management Group : organisation mondiale cre´ee´ en 1989 pour standardiser le modele` objet) H & H: Research and Training 6 / 16 Exemple -

UML Tutorial: Part 1 -- Class Diagrams

UML Tutorial: Part 1 -- Class Diagrams. Robert C. Martin My next several columns will be a running tutorial of UML. The 1.0 version of UML was released on the 13th of January, 1997. The 1.1 release should be out before the end of the year. This col- umn will track the progress of UML and present the issues that the three amigos (Grady Booch, Jim Rumbaugh, and Ivar Jacobson) are dealing with. Introduction UML stands for Unified Modeling Language. It represents a unification of the concepts and nota- tions presented by the three amigos in their respective books1. The goal is for UML to become a common language for creating models of object oriented computer software. In its current form UML is comprised of two major components: a Meta-model and a notation. In the future, some form of method or process may also be added to; or associated with, UML. The Meta-model UML is unique in that it has a standard data representation. This representation is called the meta- model. The meta-model is a description of UML in UML. It describes the objects, attributes, and relationships necessary to represent the concepts of UML within a software application. This provides CASE manufacturers with a standard and unambiguous way to represent UML models. Hopefully it will allow for easy transport of UML models between tools. It may also make it easier to write ancillary tools for browsing, summarizing, and modifying UML models. A deeper discussion of the metamodel is beyond the scope of this column. Interested readers can learn more about it by downloading the UML documents from the rational web site2. -

The Timeboxing Process Model for Iterative Software Development

The Timeboxing Process Model for Iterative Software Development Pankaj Jalote Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur – 208016; India Aveejeet Palit, Priya Kurien Infosys Technologies Limited Electronics City Bangalore – 561 229; India Contact: [email protected] ABSTRACT In today’s business where speed is of essence, an iterative development approach that allows the functionality to be delivered in parts has become a necessity and an effective way to manage risks. In an iterative process, the development of a software system is done in increments, each increment forming of an iteration and resulting in a working system. A common iterative approach is to decide what should be developed in an iteration and then plan the iteration accordingly. A somewhat different iterative is approach is to time box different iterations. In this approach, the length of an iteration is fixed and what should be developed in an iteration is adjusted to fit the time box. Generally, the time boxed iterations are executed in sequence, with some overlap where feasible. In this paper we propose the timeboxing process model that takes the concept of time boxed iterations further by adding pipelining concepts to it for permitting overlapped execution of different iterations. In the timeboxing process model, each time boxed iteration is divided into equal length stages, each stage having a defined function and resulting in a clear work product that is handed over to the next stage. With this division into stages, pipelining concepts are employed to have multiple time boxes executing concurrently, leading to a reduction in the delivery time for product releases. -

Plantuml Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2)

Drawing UML with PlantUML PlantUML Language Reference Guide (Version 1.2021.2) PlantUML is a component that allows to quickly write : • Sequence diagram • Usecase diagram • Class diagram • Object diagram • Activity diagram • Component diagram • Deployment diagram • State diagram • Timing diagram The following non-UML diagrams are also supported: • JSON Data • YAML Data • Network diagram (nwdiag) • Wireframe graphical interface • Archimate diagram • Specification and Description Language (SDL) • Ditaa diagram • Gantt diagram • MindMap diagram • Work Breakdown Structure diagram • Mathematic with AsciiMath or JLaTeXMath notation • Entity Relationship diagram Diagrams are defined using a simple and intuitive language. 1 SEQUENCE DIAGRAM 1 Sequence Diagram 1.1 Basic examples The sequence -> is used to draw a message between two participants. Participants do not have to be explicitly declared. To have a dotted arrow, you use --> It is also possible to use <- and <--. That does not change the drawing, but may improve readability. Note that this is only true for sequence diagrams, rules are different for the other diagrams. @startuml Alice -> Bob: Authentication Request Bob --> Alice: Authentication Response Alice -> Bob: Another authentication Request Alice <-- Bob: Another authentication Response @enduml 1.2 Declaring participant If the keyword participant is used to declare a participant, more control on that participant is possible. The order of declaration will be the (default) order of display. Using these other keywords to declare participants -

Descriptive Approach to Software Development Life Cycle Models

7797 Shaveta Gupta et al./ Elixir Comp. Sci. & Engg. 45 (2012) 7797-7800 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Computer Science and Engineering Elixir Comp. Sci. & Engg. 45 (2012) 7797-7800 Descriptive approach to software development life cycle models Shaveta Gupta and Sanjana Taya Department of Computer Science and Applications, Seth Jai Parkash Mukand Lal Institute of Engineering & Technology, Radaur, Distt. Yamunanagar (135001), Haryana, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The concept of system lifecycle models came into existence that emphasized on the need to Received: 24 January 2012; follow some structured approach towards building new or improved system. Many models Received in revised form: were suggested like waterfall, prototype, rapid application development, V-shaped, top & 17 March 2012; Bottom model etc. In this paper, we approach towards the traditional as well as recent Accepted: 6 April 2012; software development life cycle models. © 2012 Elixir All rights reserved. Keywords Software Development Life Cycle, Phases and Software Development, Life Cycle Models, Traditional Models, Recent Models. Introduction Software Development Life Cycle Models The Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is the entire Software Development Life Cycle Model is an abstract process of formal, logical steps taken to develop a software representation of a development process. SDLC models can be product. Within the broader context of Application Lifecycle categorized as: Management (ALM), the SDLC -

Sysml Distilled: a Brief Guide to the Systems Modeling Language

ptg11539604 Praise for SysML Distilled “In keeping with the outstanding tradition of Addison-Wesley’s techni- cal publications, Lenny Delligatti’s SysML Distilled does not disappoint. Lenny has done a masterful job of capturing the spirit of OMG SysML as a practical, standards-based modeling language to help systems engi- neers address growing system complexity. This book is loaded with matter-of-fact insights, starting with basic MBSE concepts to distin- guishing the subtle differences between use cases and scenarios to illu- mination on namespaces and SysML packages, and even speaks to some of the more esoteric SysML semantics such as token flows.” — Jeff Estefan, Principal Engineer, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory “The power of a modeling language, such as SysML, is that it facilitates communication not only within systems engineering but across disci- plines and across the development life cycle. Many languages have the ptg11539604 potential to increase communication, but without an effective guide, they can fall short of that objective. In SysML Distilled, Lenny Delligatti combines just the right amount of technology with a common-sense approach to utilizing SysML toward achieving that communication. Having worked in systems and software engineering across many do- mains for the last 30 years, and having taught computer languages, UML, and SysML to many organizations and within the college setting, I find Lenny’s book an invaluable resource. He presents the concepts clearly and provides useful and pragmatic examples to get you off the ground quickly and enables you to be an effective modeler.” — Thomas W. Fargnoli, Lead Member of the Engineering Staff, Lockheed Martin “This book provides an excellent introduction to SysML.