Swami Dayanand Saraswati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B-1 B. Rajkot-Jamnagar-Vadinar

Draft Final Report B. RAJKOT- JAMNAGAR-VADINAR Revalidation Study and Overall Appraisal of the Project for Four-Laning of Selected Road Corridors in the State of Gujarat CORRIDOR B. RAJKOT-JAMNAGAR-VADINAR CORRIDOR B.3 REVIEW OF PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDIES B.3.1 Submittal Referred To 1. The study on ‘Preparation of Pre-feasibility Study and Bidding Documents for Four Laning and Strengthening of Rajkot - Jamnagar – Vadinar Road was given to two consultants. 2. The report made available on Rajkot – Jamnagar, is the Interim Report, submitted in 2001. Therefore, review of this report has been made. However in case of Jamnagar – Vadinar the report made available and reviewed was Draft Final Report. B.3.2 Traffic Studies and Forecast B.3.2.1 Base Year Traffic Volumes 3. On Jamnagar – Vadinar section, the traffic volume surveys have been conducted at 7 locations. The base year traffic volumes have been established as given in Table B.3-1. Table B.3-1: Base Year Traffic Volume on Jamnagar–Vadinar Corridor Location ADT in Vehicles ADT in PCUs Hotel Regal Palace 10612 19383 Vadinar Junction 5208 9063 Near Sikka Junction 5808 7968 Jhakar Village 1907 2725 Shree Parotha House 4426 12378 Lalpur Junction 5341 10345 Kalavad Junction 4046 10177 4. On Rajkot – Jamnagar corridor, traffic levels recorded at three locations are as given below: Average Daily Traffic Commercial Vehicles Location Chainage Vehicles PCU PCU % Dhrol Km 49.2 4616 8296 6246 75 Phalla Km 63.3 5184 9180 7016 76 Khijadia Km 78.3 8301 13870 10000 72 B.3.2.2 Projected Traffic 5. -

Bank of Baroda

Bank of Baorda Actual disbursement of subsidy to Units will be done by banks after fulfillment of stipulated terms & conditions Date of issue 27/04/2017 vide sanction order No. 22/CLTUC/RF-14/All Banks/General/2016-17 (Amount in Rs.) Name of the unit Address Amount sanctioned Sl.No for subsidy 1 HARVI ENGINEERING R S NO 19P PLOT NO 5 NR RELIANCE TOWER PERFECT SHOWROOM GONDAL ROAD VAVDI RAJKOT 363234 2 V L ELECTRICALS 4 MAHADEVADI STATION ROAD VILLAGE GONDAL RAJKOT 666297 3 DHARTI OIL INDUSTRIES SURVEY NO 154 HIRAPAR TANKARA MORBI 225675 4 BALAJI INDUSTRIES SR NO 46/1 PLOT NO 48 NR BHAGWATI ENGINEERING B/H VICAS CORPORATION VAVDI RAJKOT 589148 5 SHREE PACKAGING PLOT NOG/828 GIDC METODA ALMIGHTY GATE KALAWAD ROAD RAJKOT 192937 6 Shreeji Agro Products bistan road, Khargone 686176 7 MARUTI PACKAGING PLOT NO 39, SURVEY NO 340P, JASDAN ROAD, B/H JALARAM TIMBER, RAJKOT 489600 8 SHK POLYMERS MANUFACTURING CO PLOT NO 139/1 OPP PATEL ALLOYS STEEL LTD PHASE1, GIDC ESTATE,VATVA,AHMEDABAD 1249171 9 JAY AMBE ENTERPRISE 131, 2ND FLOOR, MAHESHWARI INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, MAHESHWARI COMPOUND, SHAHIBAUG, AHMEDABAD 287448 10 ALPESH INDUSTRIES 9, CHANDUJI MADHAJIESTATE, MAHESHVARI MILL ROAD, TAVDIPURA, AHMEDABAD 389812 11 SANTKRUPA INDUSTRIES SANTKRUPA INDUSTRIES, BAGASARA ROAD, BORDI SAMADHIYALA, JETPUR 1500000 12 R R STEEL INDUSTRIES 1 AMARNAGAR MAIN ROAD NEAR RAJPAN MAVDI PLOT RAJKOT 360004 230343 13 CABILEX CABLES PVT LTD SURVEY NO 307 MORBI RAJKOT HIGHWAY LAJAI TANKARA MORBI 1475685 14 JAYHIND FOUNDRY NEAR JAYHIND WEIGHBRIDGE, OPP WATER TANK, ANIL STARCH MILL ROAD, NARODA ROAD 258187 15 ARROW PLAST INDUSTRIES PLOT NO 19 SURVEY NO 275P39 TIRUPATI IND PARK NR PATEL PROTEINS HADAMTALA KOTDA SANGANI 402097 16 KEYA ENGINEERING 42B JINTAN UDHYOGNAGAR SURENDRANAGAR 284006 17 Ornamac Engineering Co. -

Gujarat Council of Primary Education DPEP - SSA * Gandhinagar - Gujarat

♦ V V V V V V V V V V V V SorVQ Shiksha A b h i y O f | | «klk O f^ » «»fiaicfi ca£k ^ Annual Work Plan and V** Budget Year 2005-06 Dist. Rajkot Gujarat Council of Primary Education DPEP - SSA * Gandhinagar - Gujarat <* • > < « < ♦ < » *1* «♦» <♦ <♦ ♦♦♦ *> < ♦ *1* K* Index District - Rajkot Chapter Description Page. No. No. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Process of Plan Formulation 5 Chapter 3 District Profile 6 Chapter 4 Educational Scenario 10 Chapter 5 Progress Made so far 26 Chapter 6 Problems and Issues 31 Chapter 7 Strategies and Interventions 33 Chapter 8 Civil Works 36 Chapter 9 Girls Education 59 Chapter 10 Special Focus Group 63 Chapter 11 Management Information System 65 Chapter 12 Convergence and Linkages 66 Budget 68 INTRODUCTION GENERAL The state of Gujarat comprises of 25 districts. Prior to independence, tiie state comprised of 222 small and big kingdoms. After independence, kings were ruling over various princely states. Late Shri Vallabhbhai Patel, the than Honorable Home Minister of Government of India united all these small kingdoms into Gujarat-Bombay state (Bilingual State) during 1956. In accordance with the provision of the above-mentioned Act, the state of Gujarat was formed on 1 of May, 1960. Rajkot remained the capital of Saurashtra during 1948 to 1956. This city is known as industrial capital of Saurashtra and Kutch region. Rajkot district can be divided into three revenue regions with reference to geography of the district as follow: GUJARAT, k o t ¥ (1) Rajkot Region:- Rajkot, Kotda, Sangani, Jasdan and Lodhika blocks. -

Ceremony Is a Traditional Indian Samskara (Ceremony) Which Leads the Vatu (Child) to the Teacher

Om Sri Sairam Samoohika Upanayana Mahotsavam or Mass Thread Ceremony is a traditional Indian Samskara (ceremony) which leads the Vatu (child) to the teacher. The Upanayanam ceremony initiates the recital of the Gayatri Mantra which prays for clear intelligence, and thus starts the journey of the vatu taking his first steps to the ultimate realisation of the Reality. This along with investiture of the sacred thread or the “Yagnopavit” which is made up of three strands of thread, which signifies the three responsibilities that the child takes up upon himself: responsibility towards parents, responsibility towards Knowledge or the Master and responsibility towards society. The Gayatri mantra has the subtle power of removing evil tendencies and implanting virtuous habits, so the Upanayanam is a unique Samskara. Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba says that the Upanayanam is not only beneficial to the boys initiated but also to everyone who witnesses it and draws inspiration from it. Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba had performed many Upanayanams for individual families and for groups of children in Prasanthi Nilayam and at Brindavan Ashram. In recent memory Bhagawan had performed one such Samoohika Upanayanam at Prasanthi Nilayam on February 10th 2000 for 700 boys from the Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, 2005 in Brindavan Ashram and a Upanayanam ceremony was also conducted in 2012. On Feb 10th 2019, exactly 19 years later on the same day of the Year 2000 Samoohika Upanayanam, the Sri Sathya Sai Seva Organisations India is proposing to conduct a Samoohika Upanayanam at Prasanthi Nilayam. Important Dates & Location Date of the Upanayanam – 10th February 2019 Registration closes – 15th December 2018 or if the number of Vatus registration is full, whichever is first. -

Religious Fact Sheets

CULTURE AND RELIGION Hinduism Introduction Hinduism is the oldest and the third largest of the world’s major religions, after Christianity and Islam, with 900 million adherents. Hindu teaching and philosophy has had a profound impact on other major religions. Hinduism is a faith as well as a way of life, a world view and philosophy upholding the principles of virtuous and true living for the Indian diaspora throughout the world. The history of Hinduism is intimately entwined with, and has had a profound influence on, the history of the Indian sub-continent. About 80% of the Indian population regard themselves as Hindu. Hindus first settled in Australia during the 19th century to work on cotton and sugar plantations and as merchants. In Australia, the Hindu philosophy is adopted by Hindu centres and temples, meditation and yoga groups and a number of other spiritual groups. The International Society for Krishna Consciousness is also a Hindu organisation. There are more than 30 Hindu temples in Australia, including one in Darwin. Background and Origins Hinduism is also known as Sanatana dharma meaning “immemorial way of right living”. Hinduism is the oldest and most complex of all established belief systems, with origins that date back more than 5000 years in India. There is no known prophet or single founder of Hinduism. Hinduism has a range of expression and incorporates an extraordinarily diverse range of beliefs, rituals and practices, The Hindu faith has numerous schools of thought, has no founder, no organisational hierarchy or structure and no central administration but the concept of duty or dharma, the social and ethical system by which an individual organises his or her life. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Morbi District Is Located in the Saurashtra Region of Indian State of Gujarat

Morbi District is located in the Saurashtra region of Indian state of Gujarat. It was formed on August 15, 2013, on the 67th Independence Day of India. The district has 5 talukas - Morbi, Maliya, Tankara, Wankaner and Halvad. This district is surrounded by Kutch district to the north, Surendranagar district to the east, Rajkot district to the south and Jamnagar district to the west. Morbi, also known as Morvi is the administrative headquarters of Morbi district, which literally means City of Peacocks. The town of Morbi is endowed not only with great natural beauty, but it is also famous for its colorful history and rich cultural heritage. The town of Morbi is situated on the bank of Machchhu River, 35 km from the sea and 60 km from Rajkot. The city-state of Morbi and much of the building heritage and town planning, are attributed to the administration of Sir Lakhdhiraji Waghji, who ruled from 1922 to 1948. The Machchhu dam failure or Morbi disaster was a dam-related flood disaster which occurred on 11 August 1979. Morbi has long been a center for trade and industry. In the beginning, the economy of the town was mainly dependent on ceramic and clock manufacturing industry. Today, the area has also become a growing hub for paper mills and other ancillary industries such as packaging industry, export houses etc. Together, they have created a vibrant and sustainable economy in this region. After the bifurcation from Rajkot District Court, Morbi District Court started its functioning from 02/10/2016 and presently, there are 2 Appellate Courts, 1 Family Court, 1 Labour Court, 5 Senior Division Courts/Chief Courts & 7 Junior Division Courts, are functioning in Morbi District. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

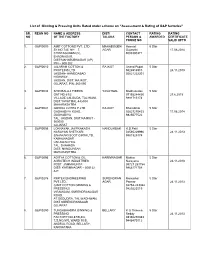

List of Ginning & Pressing Units Rated Under Scheme on “Assessment

List of Ginning & Pressing Units Rated under scheme on “Assessment & Rating of G&P factories” SR. REGN NO NAME & ADDRESS DIST/ CONTACT RATING RATING NO OF THE FACTORY TALUKA PERSON & AWARDED CERTIFICATE PHONE NO VALID UPTO 1. G&P/0009 AMIT COTTONS PVT. LTD MAHABOOBN Hemant 5 Star SY.NO.745, NH – 7, AGAR Gujarathi 17.08.2014 CHINTAGUDEM (V), 9000300371 EHADNAGAR, DIST:MAHABUBNAGAR (AP) PIN – 509 202 2. G&P/0010 JALARAM COTTON & RAJKOT Anand Popat 5 Star PROTEINS LTD 9426914910 24.11.2013 JASDAN- AHMEDABAD 02821222201 HIGHWAY, JASDAN, DIST: RAJKOT, GUJARAT, PIN: 360 050 3. G&P/0034 SHRI BALAJI FIBERS YAVATMAL Madhusudan 5 Star GAT NO:61/2 07153244430 27.6.2015 VILLAGE LALGUDA, TAL:WANI, 9881715174 DIST:YAVATMAL-445304 MAHARASHTRA 4. G&P/0041 GIRIRAJ COTEX P.LTD RAJKOT Bharatbhai 5 Star GADHADIYA ROAD, 02827270453 17.08.2014 GADHADIYA 9825077522 TAL: JASDAN, DIST;RAJKOT - 360050 GUJARAT 5. G&P/0056 LOKNAYAK JAYPRAKASH NANDURBAR R.D.Patil 5 Star NARAYAN SHETKARI 02565229996 24.11.2013 SAHAKARI SOOT GIRNI LTD, 9881925174 KAMALNAGAR UNTAWAD HOL TAL. SHAHADA DIST: NANDURBAR MAHARASHTRA 6. G&P/0096 ADITYA COTTON & OIL KARIMNAGAR Mukka 5 Star AGROTECH INDUSTRIES Narayana 24.11.2013 POST: JAMMIKUNTA 08727 253754 DIST: KARIMNAGAR – 505122 9866171754 A.P. 7. G&P/027 6 RIMTEX ENGINEERING SURENDRAN Manubhai 5 Star PVT.LTD., AGAR Parmar 24.11.2013 (UNIT COTTON GINNING & 02752-243322 PRESSING) 9825223519 VIRAMGAM, SURENDRANAGAR ROAD, AT.DEDUDRA, TAL.WADHWAN, DIST SURENDRANAGAR GUJARAT 8. G&P/0290 TUNGABHADRA GINNING & BELLARY K G Thimma 5 Star PRESSING Reddy 24.11.2013 FACTORY,NO.87/B,3/4, 08392250383 T.S.NO.970, WARD 10 B, 9448470112 ANDRAL ROAD, BELLARY, KARNATAKA 9. -

Econol\HC GEOLOGY and ~HNERAL. RESOURCES of SAURASHTRA

·I THE- . ECONOl\HC GEOLOGY AND ~HNERAL. RESOURCES OF SAURASHTRA (With a Mineral Map of Saurashtra) BY. B. C. ROY, D.I.C., M.Sc. (London), Dr.-lng. (Freiberg), Superintending Geologist-in-charge, Western Circle,. Geological Survey of India. Published by Government of Saurashtra, Department of Industry and Supply, RA.JKOT Price: Rs. 10/- 1953 THE ECONOMIC GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF SAURASHTRA I THE ECONOMIC GEOLOGY AND 1\IINERAL RESOURCES OF SAURASHTRA (With a Mineral Map of Saurashtra) BY B. C. ROY, D.i.C., M.Sc. (London), Dr.-Ing, (Freiberg), Superintending Geologist-ifr,.charge, Western. Circle, Geological Survey of India Published by Government of Saurashtra, Department of. Industry and Supply, RA.JKOT Price: Rs. 10.'- 1953 Printed by G. G. Pathare at the Popular Press (Bombay) Ltd., 35, Tardeo Road, Bombay 7, for the Popular Book Depot., and published by Government of Saurashtra, Department of Industry and Supply. CONTENTS PART I.-ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF GEOLOGY IN SAURASHTRA 11,\(;r. CHAPTER I. -INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER II. -MINERAL PRODUCTION 5 CHAPTER III. -PHYSIOGRAPHY 8 Hills 8 Climate 10 Rainfall 11 Rivers 11 Lakes 12 Islands 12 Salt wastes 12 CRAPTER IV. -GENERAL GEOLOGY 14 Umia beds 14 W adhwan sandstones 15 Trappean grits 16 Deccan traps 16 Inter-trappeans 19 Trap-dykes 19 Lateritic rocks 21 Gaj beds. 21 Dwarka beds 2.'1 Miliolite series 24 Alluvium 25 CHAPTER v. -GEOLOGY IN ENGINEERING AND AGRICULTURE .. 27 General .. 27 Underground water supply 27 Dam sites and reservoirs .. 28 Road and railway alignments 30 Tunnelling 30 Airports .. 31 Docks and harbours 31 Bridge foundations 31 Building foundations 32 Construction materials 33 Soils 34 CHAPTER VI. -

VG-2017 MSME - Approved Investment Intentions District : Morbi Sr.No

VG-2017 MSME - Approved Investment Intentions District : Morbi Sr.No. Name of Company Registered Office Address 1 A one Industries rafaleshwar,,Makansar-363642,Morvi,Morbi 2 Aaaran Minerals 50,51 rafaleshwar GIDC,,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi 3 Aai krupa cotton thoriyali road,tankara,,Tankara-363650,Tankara,Morbi 4 aarav halvad,,Halvad-363330,Halvad,Morbi 5 AaRAV Flour Mill Ratabhe,,Ratabhe-363330,Halvad,Morbi 6 airson poly industries surve no 258/p1 maruti plsatic,,Hadmatiya-363650,Tankara,Morbi 7 ajana govindbhai tankara,,Nana Khijadiya-363650,Tankara,Morbi 8 ajnata oil mill ghuntu,,Ghuntu-363642,Morvi,Morbi 9 Alfa Industries near maruti cold storage,chhattar,,Chhattar-363650,Tankara,Morbi 10 Altimo Industries 30 , rafaleshwar GIDC estate,,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi 11 Altra Pack Ind. Ghuntu,,Ghuntu-363642,Morvi,Morbi 12 ambidhara oil industries dulkot,,Morvi-363642,Morvi,Morbi 13 Amerys special refactory vaghasia,,Vaghasia-363621,Wankaner,Morbi 14 AMRUT CERA COAT PLOT NO 151 RAFALESHWAR GIDC ESTATE,RAFALESHWAR,Morvi-360641,Morvi,Morbi 15 AMRUT CERA COTE PLOT NO.151,RAFALESHWAR GIDC ESTATE,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi 16 amul oil industriel kadiyana,,Kadiyana-363330,Halvad,Morbi 17 ANAND K VAGHELA PLOT NO.39,VAGHASIYA GIDC ESTATE,Vaghasia-Wankaner,Morbi 18 ANAND MINERALS PLOT NO.45,RAFALESHWAR GIDC ESTATE,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi 19 ANGEL PLASTIC INDUSTRIES K-1-GIDC,SANALA ROAD MORBI,,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi 20 antique cottex hirapar,latipar highway road,,Hirapar-363650,Tankara,Morbi 21 antique designer tiles plot no 2 rafaleshwar gidc estate,rafaleshwar,Morvi-360641,Morvi,Morbi 22 ANTIQUE PVC PIPE PLOT NO.146,RAFALESHWAR GIDC ESTATE,Morvi-Morvi,Morbi Page 1 of 19 VG-2017 MSME - Approved Investment Intentions District : Morbi Sr.No. -

Importance of Upanayanam Rites in Current Scenario and Its Rich Historical Background-A Research Article

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science: Insights & Transformations Vol. 5, Issue 2 – 2020 ISSN: 2581-3587 Importance of Upanayanam Rites in Current Scenario and Its Rich Historical Background-A Research Article Ajay Krishan Tiwari1 1Sr.Lecturer of CTE / BTTC-G.V.M & Former H.O.D Department of Education - IASE Deemed to be University, Sardarshahar. Abstract Upanayan or say Yagyopaveet or Vidhyaadhyana can also be called the rite of initiation. Upanayana rites-Yagyopaveet is the tenth rite of Hinduism This is a very important ritual in Hinduism. It can be called the tenth sacrament in sixteen rites. Because this ninth ritual is performed after Karnabheda. The main purpose of this rite is to pave the way for the material and spiritual progress of the native. Assisted in the study of Vedas, teaching education, kalpa, grammar, verses, astrology, called Nirukta as Vedarya goes. Among these, the Vedāryān called ‘Shiksha’ is the beginning of the Veda mantras (in the text, rituals of ‘Kalpa’ Veda mantras And for the knowledge of Yagya rituals, the meaning of Vedic verses (words) in the Nirukta Ved Mantras. In making knowledge, astrology and rituals for the knowledge of verses used in Vedic mantras Provide great help in providing knowledge of the appropriate time and muhurta for various activities etc. Keywords: Upanayan, Vidhyaadhyana, Rich Historical Background, Parskar-Grihyasutra, Brahmacharya-Ashram. Preface The rites that are performed to initiate the education of the native are called the Upanayan rites. Since education is a continuous process in human life, all round development of the learner. Initially, when the Jataka was considered worthy that he is now able to acquire knowledge from the Gurus, then at that stage the Jataka was performed.