The Construction of Precarity in Refugee and Migrant Discourse” R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POL 380 QUEER IR Winter 2020 Instructor: Dr. Julie Moreau Email

POL 380 QUEER IR Winter 2020 Instructor: Dr. Julie Moreau Email: [email protected] Class Time and Location: Tuesday 6-8pm, ES B142 Office hours: Tuesdays, 12:30-1:30 or by appointment Office Location: Sidney Smith Hall, room 3009 Course Description Are states straight? This course will tackle this and other questions at the intersection of sexuality and international relations. The first part of the course takes a critical look at fundamental concepts in international relations such as anarchy, sovereignty, security and cooperation. The second part applies queer IR theory to case studies such as the spread right-wing populism in Europe and the Americas, international funding contingent on adoption of LGBT rights, and the institutionalization of SOGI terminology at the UN. By the end of the course, students will be able to use queer theory to articulate the strengths and limitations of core theoretical concepts in international relations and explain contemporary global politics. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Professionalism and Participation: • To practice arriving prepared for group meetings • To listen and consider the arguments and perspectives of others • To actively engage course concepts with colleagues in-class through writing and speaking Critical Thinking and Writing Skills: • To critically engage IR paradigms and core concepts • To expand knowledge and understanding of contemporary global issues • To develop written argumentation, organization, and evidentiary skills Extension and Collaboration Skills • To create original work that synthesizes course concepts • To connect real world examples to Queer and IR theory • To collaborate with colleagues ASSESSMENT OF LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1) Professionalism and Participation a) In-Class Participation Activities (5%) I do not take attendance in class. -

WPATH 2018 Symposium Schedule

WPATH 2018 Symposium Schedule Saturday, November 3, 2018 17:00 - 19:30 Pacifico A Opening Session Mayor of Buenos Aires - Horacio Rodriguez Larreta Deputy Mayor of Buenos Aires - Diego Santilli Argentinian Federal Minister of Health - Adolfo Rubinstein President’s Plenary 18:00 - TRANSGENDER GLOBAL HEALTH Gail Knudson 18:30 - OPPORTUNITY DENIED: EXAMINING EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINATION AGAINST TRANS PEOPLE Sam Winter 19:00 - TRANS LEGAL HISTORY IN LATIN AMERICA Tamara Adrian Sunday, November 4, 2018 8:30 - 10:00 Atlantico B Mini-Symposia – Education 8:30 - TALKING SCIENCE WITH TRANSGENDER CLIENTS Laura Erickson-Schroth, MA, MD1; Jaimie Veale, PhD2; Rachel Levin, PhD3; E. Edmiston, PhD4 1Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA; 2University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand; 3Pomona College, Claremont, CA, USA; 4University of PittsburGh, PittsburGh, PA, USA Atlantico C Oral – Medicne Adult: Effects of Cross Sex Hormone Treatment 8:30 - MORTALITY IN TRANSGENDER PEOPLE RECEIVING HORMONE TREATMENT: RESULTS OF A NATIONWIDE COHORT STUDY Christel De Blok, MD; Chantal Wiepjes, MD; Annemieke Staphorsius, MS; Martin Den Heijer, MD, PhD VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands Oral – Medicne Adult: Effects of Cross Sex Hormone Treatment 8:45 - SUBJECTIVE COMPLAINTS DURING HORMONE TREATMENT OF TRANSGENDER INDIVIDUALS - RESULTS FROM THE EUROPEAN NETWORK FOR THE INVESTIGATION OF GENDER INCONGRUENCE - Dennis Van Dijk, MD1; Marieke Dekker, MD, PhD1; Kasper Overbeek, MD2; Maartje Klaver, MD1; Alessandra Fisher, MD, PhD3; Guy T'Sjoen4; -

Summary Conclusions 2021 Global Roundtable On

ROUNDTABLE SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS REPORT: FULL VERSION SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS 2021 GLOBAL ROUNDTABLE ON PROTECTION AND SOLUTIONS FOR LGBTIQ+ PEOPLE IN FORCED DISPLACEMENT Co-organized by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the United Nations Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (IE SOGI) 07 – 29 June 2021 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Division of International Protection – Geneva Mandate of the United Nations Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (IE SOGI) 16 August 2021 1 ROUNDTABLE SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS REPORT: FULL VERSION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have contributed to the design, organization and implementation of the 2021 Global Roundtable on Protection and Solutions for LGBTIQ+1 People in Forced Displacement, and in particular to the consultative multi-stakeholder elaboration of the key challenges, good practices and recommendations highlighted herein. Preparation of the Roundtable and of these Summary Conclusions were led by UNHCR and by the Mandate of the United Nations Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (IE SOGI). Inputs from LGBTIQ+ people with lived experience of forced displacement and/or statelessness, as well as from other humanitarian, human rights and development stakeholders across sectors have greatly enriched the Roundtable and its findings. The -

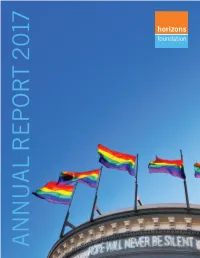

2017 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Horizons Foundation envisions a world where all people live free from prejudice and discrimination, and where LGBTQ people contribute to and thrive in a vibrant, diverse, giving, and compassionate community. VISION A community foundation rooted in and dedicated to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community, we exist to: • Mobilize and increase resources for the LGBTQ movement and organizations that secure the rights, meet the needs, and celebrate the lives of LGBTQ people • Empower individual donors and promote giving as an integral part of a healthy, compassionate community MISSION • Steward a permanently endowed fund through which donors can make legacy gifts to ensure our community’s capacity to meet the needs of LGBTQ people, now and forever. 2017will not easily be forgotten. Even as the LGBTQ movement notched at least a handful of victories, 2017 also brought a painful and sudden reminder that we cannot take our rights for granted. Our progress remains, in too many ways, fragile. At the same time, 2017 reminded us of the generosity of our Horizons family. Thanks to the support of donors like you, Horizons grew significantly, ending the year with assets nearing $35 million. That success enabled us to award more than $2.5 million in grants to a wide array of nonprofits that advocate for and serve our community day in and day out. Simultaneously, donor commitments to making legacy gifts to the foundation also rose, reaching more than $65 million in future gifts that will benefit LGBTQ people for decades and decades ahead. Perhaps in a different era, these achievements might fill our Annual Report, along with a few profiles about our grantees and the lives they touch. -

Chechnya, Detention Camps In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Chechnya, Detention Camps in Perla, Héctor, Jr. “Si Nicaragua Venció, El Salvador Vencerá: procedures for acquiring refugee status outside Russia. Central American Agency in the Creation of the U.S.–Central The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs assisted in American Peace and Solidarity Movement.” Latin American – obtaining international passports, while some European Research Review 43, no. 2 (2008): 136 158. Union states expressed readiness to accommodate the Perla, Héctor, Jr. “Heirs of Sandino: The Nicaraguan Revolution ” victims (Ponniah 2017). By mid-summer 2017, 120 and the U.S.-Nicaragua Solidarity Movement. Latin American persons had applied to the Russian LGBT Network for Perspectives 36, no. 6 (2009): 80–100. help, 75 had been evacuated, and 27 had left Russia Roque Ramírez, Horacio N. “Claiming Queer Cultural Citizen- (Russian LGBT Network 2017b). In September, the ship: Gay Latino (Im)migrant Acts in San Francisco.” In Queer Migrations: Sexuality, U.S. Citizenship, and Border Crossings, Canadian charity organization Rainbow Railroad reported edited by Eithne Luibhéid and Lionel Cantú Jr., 161–188. that another 35 victims were granted refugee status in Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005. Canada (Gilchrist 2017). Yet, detentions in Chechnya Rose, Kieran. “Lesbians and Gay Men.” In Nicaragua: An continued as of 2017. Unfinished Canvas, edited by Nicaraguan Book Collective, 83–85. Dublin: Nicaraguan Book Collective, 1988. How the Camps Were Established Schapiro, Naomi. “AIDS Brigade: Organizing Prevention.” In AIDS: The Women, edited by Ines Rieder and Patricia Ruppelt, At the outset, the antigay campaign in Chechnya was 211–216. -

Partnering with Rainbow Railroad: Three Recommendations for U.S

Partnering with Rainbow Railroad: Three recommendations for U.S. Policy-makers JUNE 1, 2021 Partnering with Rainbow Railroad: Three Recommendations for U.S. Policy-Makers Table of Contents Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Our Priority Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Recommendation 1: Increase refugee admissions to the U.S. for LGBTQI+ populations given their unique vulnerabilities ...................................... 6 Recommendation 2: Grant LGBTQI+ refugee organizations like Rainbow Railroad official recognized referral status ................................................ 7 Recommendation 3: Protect the right of asylum by ensuring that harmful and discriminatory detention policies are reversed, and that dentition is safe for LGBTQI+ migrants. ........................................................................................................... 9 The Case for Partnership with Rainbow Railroad ......................................................................................................................................10 Acronyms HRD: Human Rights Defender IDP: Internally Displaced Person LGBTQI+: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Plus OHCHR: Office of the United -

Mapping Trans and Gender Non-Conforming Refugee Narratives in Canada's Refugee Regime Tai Jacob Departmen

Embodied migrations: Mapping trans and gender non-conforming refugee narratives in Canada’s refugee regime Tai Jacob Department of Geography McGill University, Montreal May 2020 A thesis submitted to McGill in partial fulfillment of the requirements of a degree of a Master of Arts Table of Contents Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. V ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... VI 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 A note on terminology ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Thesis research aims and objectives ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Indigenous sovereignty and migrant justice ........................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Refugee law and SOGIE refugees in Canada ...................................................................................................... 5 1.6 SOGIE refugees and LGBT migration -

Rainbow Railroad

Due Diligence - Grant This accomplishes University Impact’s charitable purposes by helping LGBTQI+ individuals at risk of violence and persecution relocate to welcoming countries. Associates: Andrea Terminel [email protected]; Sophie de Bruyn [email protected]; Kirstin Detering - [email protected] University Impact’s Rainbow Railroad Recommendation: Approval of an unrestricted grant to Rainbow Railroad awarded in $15,000 increments Company Information Legal Name Rainbow Railroad Entity Type: Nonprofit Incorporation Date 2006 Corporate Address Toronto, Ontario Website https://www.rainbowrailroad.org/ Social Problem: In over 70 countries there are laws that criminalize same sex intimacy and discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Members of the LGBTQI+ community often face violence and persecution in these settings. UN SDG: 10. (Reduced inequalities) Business overview Theory of Change: An interconnected community of LGBTQI+ human rights defenders, facilitated by Rainbow In over 70 countries, there are laws that criminalize same sex intimacy Railroad, can provide an alternative pathway to safety and discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In 8 for people whose lives are at risk just because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. of these countries, same sex intimacy is punishable by death. As a result, there are 122 million LGBTQI+ individuals living in countries where their Intervention: Rainbow Railroad offers emergency travel support (ETS) and ad-hoc secondary support to LGBTQI+ sexual orientation may lead to violence and persecution or they may face individuals seeking safety from state-sponsored discrimination when applying for work, housing, education or when persecution. seeking medical attention. Outputs: Individuals moved to safety 800+ Rainbow Railroad’s key intervention is to offer travel support to LGBTQI+ Countries relocated from 43 individuals who are in high-risk/dangerous environments. -

Prairie & Northern Territories (PNT) LGBTQ+ Newcomers Settlement Conference, Sept 25 & 26 2017

Prairie & Northern Territories (PNT) LGBTQ+ Newcomers Settlement Conference, Sept 25 & 26 2017 Evaluation Report By: Bronwyn Bragg, MA Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Key themes ................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Barriers facing LGBTQ+ newcomers ..................................................................................... 5 2. Service gaps for LGBTQ+ newcomers .................................................................................... 6 3. Research and data are a challenge ......................................................................................... 7 4. Promising practices and room to grow ................................................................................ 8 5. Opportunities moving forward ............................................................................................... 8 Results from breakout discussions ................................................................................ 10 Areas of investment (summarized from six breakout sessions) .................................... 10 Action planning ..................................................................................................................... 12 Action items to move forward .................................................................................................... 12 Summary -

Annual Report 2016 Strengthening Each Other Thanks and Acknowledgements

annual report 2016 Strengthening each other Thanks and acknowledgements The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association is grateful for the work and support of its volunteers, staff and Executive Board. A heartfelt thank you goes to the members of ILGA: not only for their financial support, but also for the time and energy they commit to furthering ILGA’s aims and objectives. Last but not least, our thanks to the following organisations: ILGA’s 2016 Annual Report was coordinated and edited by Daniele Paletta. Managed by Renato Sabbadini. Spanish translation: Paul Caballero Graphic design: Luca Palermo for EdLine Adv Pictures (unless otherwise stated, and except pages 16-17 and 40): Jacuzzi News This annual report covers the period from 1 January to 31 December 2016. 02 | ILGA Annual Report 2016 Advancing equality The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) is a worldwide federation of organisations committed to equal human rights for LGBTI people and their liberation from all forms of discrimination. Founded in 1978, it enjoys consultative status at the United Nations, where it speaks and lobbies on behalf of more than 1,200 member organisations from 132 countries. Vision Strategic plan 2014-2018 ILGA is committed to help shap- become a representative voice rights standards and principles ing a world where the human of LGBTI civil society within without discrimination based on rights of all are respected; where international organisations, par- sexual orientation, gender iden- everyone can live in equality and ticularly the United Nations, tity and/or gender expression, freedom; where global justice through collaboration, engage- and sex (intersex). -

Partnering with Rainbow Railroad: Three Recommendations for U.S

Partnering with Rainbow Railroad: Three recommendations for U.S. Policy-makers EXECUTIVE SUMMARY JUNE 1, 2021 PARTNERING WITH RAINBOW RAILROAD | THREE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR U.S. POLICY-MAKERS Overview In 2019, 79.5 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide due to “persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order.” At the same time, some 71 countries around the world currently have laws that criminalize same-sex behaviour, and no fewer than 15 criminalize gender diversity. These laws, often legacies of colonization, are powerful tools of repression and extortion. As a consequence, LGBTQI+ people are routinely arrested and denied basic human rights; often, they are brutally attacked, tortured or even murdered. The lockdowns and border closures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have only exacerbated this situation. Of particular concern over the past year are instances of police abuse and brutality enacted under the guise of enforcing COVID-19 quarantine measures, as seen in a number of countries including Uganda, Egypt and Jamaica. Over the course of its 15 year history, Rainbow Railroad has helped over 1,600 LGBTQI+ individuals find safe haven from state-enabled harassment and violence through emergency relocations and other forms of assistance.Our goal is to work with governments and policy-makers to create more pathways to safety for LGBTQI+ asylum seekers and abolish repressive laws that persecute LGBTQI+ individuals around the world. Our Priority Recommendations 1. Increase refugee admissions to the U.S. for LGBTQI+ populations given their unique vulnerabilities 2. Grant LGBTQI+ refugee organizations like Rainbow Railroad official recognized referral status 3. -

Rainbow Railroad 2020-2022 Strategic Plan

2020-2022 Strategic Plan A note from the Executive Director and Chairs of the Board » Since our founding in 2006, we have helped over 800 people find safety. Of these We have developed a three-year strategy 800, the vast majority have received assistance from us since 2016, when we that emphasizes sustained growth and implemented our three-year strategic plan. That plan focused on three goals: deepen and broaden services, expand reach to people with new tools and build capacity to operational improvement. meet the organization’s needs. Ultimately we surpassed many of these goals, and grew at a rapid pace. With this plan, by the end of 2022, we will: • Double the amount of people we have helped Around the world LGBTQI people The global refugee crisis is exasperating continue to face oppression worldwide; the plight of LGBTQI people worldwide. • Expand the definition of what it means to provide support in over 70 countries there are laws According to The United Nations High • Increase our regional diversity and the gender demographics that criminalize same sex intimacy and Commissioner for Refugees, there are of the people we serve; and discriminate on the basis of sexual now over 70 million displaced people in • Build the capacity necessary to accomplish these goals. orientation or gender identity. In eight the world – the largest number since the countries same sex intimacy is punishable Second World War. For many reasons, By 2022, we will be an even stronger and more robust organization, equipped to by death. LGBTQI people face unique challenges provide a lifeline to LGBTQI people facing imminent danger.