A Decade of Change: Donegal and Ireland 1912 - 1923

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dún Na Ngall 1919 -1925 from Conflict to Division

FROM CONFLICT TO DIVISION - DONEGAL 1919-1925 DIVISION - DONEGAL TO FROM CONFLICT FROM CONFLICT TO DIVISION DONEGAL 1919-1925 DÚN NA NGALL 1919-1925 NGALL NA DÚN Ó CHOIMHLINT GO DEIGHILT DEIGHILT GO CHOIMHLINT Ó Ó CHOIMHLINT GO DEIGHILT DÚN NA NGALL 1919-1925 Ó CHOIMHLINT GO DEIGHILT County Museum County Réamhrá Donegal Dhún na nGall na Dhún Músaem Chontae Chontae Músaem B’fhéidir go bhfuil an tréimhse 1912 – 1923 ar na tréimhsí is tábhachtaí i stair na hÉireann. Rinne na heachtraí a tharla le linn na mblianta sin athrú ó bhonn ar oileán na hÉireann agus d’fhág siad lorg buan ar pholaitíocht agus ar shochaí na hÉireann suas go dtí an lá inniu. under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 Initiative. 2012-2023 Centenaries of Decade the under Sna blianta roimh an Chéad Chogadh Domhanda tháinig méadú ar an Media and Sport Gaeltacht, Arts, Culture, Tourism, of Department the by supported was booklet This Culture Division, Donegal County Council. County Donegal Division, Culture teannas idir an dream a bhí ag iarraidh fanacht san Aontas agus an dream Museum, County Donegal McCarthy, Judith and Carr Caroline by edited and written was booklet This a bhí ag iarraidh níos mó neamhspleáchais d’Éirinn. Bunaíodh dhá fhórsa a bhí in éadan a chéile – Óglaigh Uladh agus Óglaigh na hÉireann – agus bhí céim tugtha i dtreo cogadh cathartha in Éirinn. Le tús an chogaidh War. Civil the and Independence of War the to lead ultimately would cuireadh moill ar choimhlint ar bith a d’fhéadfadh tarlú ach ní raibh na which set being was path new A Westminster. -

Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland

Creating Citizens from Colonial Subjects: Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland Dr. Arlene Crampsie School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy University College Dublin ABSTRACT: Despite the incorporation of Ireland as a constituent component of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the 1801 Act of Union, for much of the early part of the nineteenth century, British policy towards Ireland retained its colonial overtones. However, from the late 1860s a subtle shift began to occur as successive British governments attempted to pacify Irish claims for independence and transform the Irish population into active, peaceful, participating British citizens. This paper examines the role played by the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898 in affecting this transformation. The reform of local government enshrined in the act not only offered the Irish population a measure of democratic, representative, local self- government in the form of county, urban district, and rural district councils, but also brought Irish local government onto a par with that of the rest of the United Kingdom. Through the use of local and national archival sources, this paper seeks to illuminate a crucial period in Anglo-Irish colonial relations, when for a number of years, the Irish population at a local level, at least, were treated as equal imperial citizens who engaged with the state and actively operated as its locally based agents. “Increasingly in the nineteenth century the tentacles of the British Empire were stretching deep into the remote corners of the Irish countryside, bearing with them schools, barracks, dispensaries, post offices, and all the other paraphernalia of the … state.”1 Introduction he Act of Union of 1801 moved Ireland from the colonial periphery to the metropolitan core, incorporating the island as a constituent part of the imperial power of the United TKingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996

33 Conor Curran ‘It has almost been an underground movement’. The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996 Abstract This article assesses the development of association football at grassroots’ level in County Donegal, a peripheral county lying in the north-west of the Republic of Ire- land. Despite the foundation of the County Donegal Football Association in 1894, soccer organisers there were unable to develop a permanent competitive structure for the game until the late 20th century and the more ambitious teams were generally forced to affiliate with leagues in nearby Derry city. In discussing the reasons for this lack of a regular structure, this paper will also focus on the success of the Donegal League, founded in 1971, in providing a season long calendar of games. It also looks at soccer administrators’ rivalry with those of Gaelic football there, and the impact of the nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association’s ‘ban’ on its members taking part in what the organisation termed ‘foreign games’. In particular, the extent to which the removal of the ‘ban’ in 1971 helped to ease co-operation between organisers of Gaelic and Association football will be explored. Keywords: Association football; Gaelic football; Donegal; Ireland; Donegal League; Gaelic Athletic Association Introduction The nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which is today the leading sporting organisation in Ireland despite its players having to adhere to its amateur ethos, has its origins in the efforts of schoolteacher and journalist Michael Cusack, who was eager to reform Irish athletics which was dominated by elitism and poorly governed in the early 1880s. -

Official U.S. Bulletin

: — : : : : k PVBLISHEn BJilLY under order of THE PRESIDENT of THE UNITED STATES by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman -k * ic COMPLETE Record of U. S, GOVERNMENT Activities VoL. 3 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUAEY 11, 1919. No. 535 TRADE WITH FINLAND MAY BE ORDERS TO COMPLETE PAY Army Post Exchanges RESUMED UNDER REGULATION OF SOLDIERS IN ARREARS Are Forbidden to Sell Unauthorized Insignia SAYS THE WAR TRADE BOARD ARRIVING AT CAMPS WITH The War Department authorizes OUTLINE OF PROCEDURE IS GIVEN A “CONVALESCENT CENTER” publication of the following Under direction of the Secretary List of Commodities Which Do Not of War an order has been issued as INSTRUCTIONS ALSO follows Require Import Certificates From 1. “ It has been brought to the Inter-Allied Trade Committee SENT ARMY HOSPITALS attention of the War Department if that post exchanges and similar Applications Are in Order. Detachment Commanders places are selling unauthorized in- signia such as service ribbons and The War Trade Board announces, in a and Disbursing Officers gold and silver stars to be worn on new ruling (W. T. B. R. 590), supple- the uniform.” Required to See That En- menting AV. T. B. R. 577, issued February 2. “ Responsible officers will take 5, 1919, that arrangements have now been immediate steps to have such listed Men Are Promptly made whereby both export shipments to practice discontinued by post ex- and import shipments from Finland may Paid Reports to changes and stores under their im- — Be Made be resumed. mediate jurisdiction. At the same All shipments for export to tlie above- by Wire Direct to Director time every effort will be made to mentioned country must be covered by an influence stores located near posts, of Finance, War Depart- import certificate issued by the interallied camps, or cantonments, discon- to trade committee, at Helsingfors, except tinue the practice.” ment, Washington. -

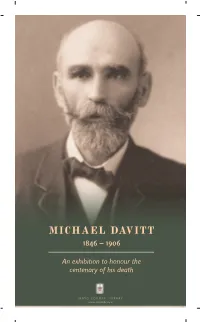

Michael Davitt 1846 – 1906

MICHAEL DAVITT 1846 – 1906 An exhibition to honour the centenary of his death MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY www.mayolibrary.ie MAYO COUNTY LIBRARY MICHAEL DAVITTwas born the www.mayolibrary.ie son of a small tenant farmer at Straide, Co. Mayo in 1846. He arrived in the world at a time when Ireland was undergoing the greatest social and humanitarian disaster in its modern history, the Great Famine of 1845-49. Over the five or so years it endured, about a million people died and another million emigrated. BIRTH OF A RADICAL IRISHMAN He was also born in a region where the Famine, caused by potato blight, took its greatest toll in human life and misery. Much of the land available for cultivation in Co. Mayo was poor and the average valuation of its agricultural holdings was the lowest in the country. At first the Davitts managed to survive the famine when Michael’s father, Martin, became an overseer of road construction on a famine relief scheme. However, in 1850, unable to pay the rent arrears for the small landholding of about seven acres, the family was evicted. left: The enormous upheaval of the The Famine in Ireland — Extreme pressure of population on Great Famine that Davitt Funeral at Skibbereen (Illustrated London News, natural resources and extreme experienced as an infant set the January 30, 1847) dependence on the potato for mould for his moral and political above: survival explain why Mayo suffered attitudes as an adult. Departure for the “Viceroy” a greater human loss (29%) during steamer from the docks at Galway. -

Robert John Lynch-24072009.Pdf

THE NORTHERN IRA AND THE EARY YEARS OF PARTITION 1920-22 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling. ROBERT JOHN LYNCH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DECEMBER 2003 CONTENTS Abstract 2 Declaration 3 Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Chronology 6 Maps 8 Introduction 11 PART I: THE WAR COMES NORTH 23 1 Finding the Fight 2 North and South 65 3 Belfast and the Truce 105 PART ll: OFFENSIVE 146 4 The Opening of the Border Campaign 167 5 The Crisis of Spring 1922 6 The Joint-IRA policy 204 PART ILL: DEFEAT 257 7 The Army of the North 8 New Policies, New Enemies 278 Conclusion 330 Bibliography 336 ABSTRACT The years i 920-22 constituted a period of unprecedented conflct and political change in Ireland. It began with the onset of the most brutal phase of the War of Independence and culminated in the effective miltary defeat of the Republican IRA in the Civil War. Occurring alongside these dramatic changes in the south and west of Ireland was a far more fundamental conflict in the north-east; a period of brutal sectarian violence which marked the early years of partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland. Almost uniquely the IRA in the six counties were involved in every one of these conflcts and yet it can be argued was on the fringes of all of them. The period i 920-22 saw the evolution of the organisation from a peripheral curiosity during the War of independence to an idealistic symbol for those wishing to resolve the fundamental divisions within the Sinn Fein movement which developed in the first six months of i 922. -

Palestine in Irish Politics a History

Palestine in Irish Politics A History The Irish State and the ‘Question of Palestine’ 1918-2011 Sadaka Paper No. 8 (Revised edition 2011) Compiled by Philip O’Connor July 2011 Sadaka – The Ireland Palestine Alliance, 7 Red Cow Lane, Smithfield, Dublin 7, Ireland. email: [email protected] web: www.sadaka.ie Bank account: Permanent TSB, Henry St., Dublin 1. NSC 990619 A/c 16595221 Contents Introduction – A record that stands ..................................................................... 3 The ‘Irish Model’ of anti-colonialism .................................................................... 3 The Irish Free State in the World ........................................................................ 4 The British Empire and the Zionist project........................................................... 5 De Valera and the Palestine question ................................................................. 6 Ireland and its Jewish population in the fascist era ............................................. 8 De Valera and Zionism ........................................................................................ 9 Post-war Ireland and the State of Israel ............................................................ 10 The UN: Frank Aiken’s “3-Point Plan for the Middle East” ................................ 12 Ireland and the 1967 War .................................................................................. 13 The EEC and Garret Fitzgerald’s promotion of Palestinian rights ..................... 14 Brian Lenihan and the Irish -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST.