Emergency Admissions: a Journey in the Right Direction?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ian Gilmore Chair, UK Alcohol Health Alliance President, British Society of Gastroenterology Reflections on the ……

Ian Gilmore Chair, UK Alcohol Health Alliance President, British Society of Gastroenterology Reflections on the …… •challenges for hepatology •challenges for gastroenterology •challenges for the acute hospital •Challenges for the system •Challenges for society Challenges for hepatology Challenges for hepatology • Existing workforce (consultant, juniors, nurses • Recruitment into specialty • Relationship with gastroenterology • Relationship with G(I)M Challenges for gastroenterology Challenges for gastroenterology • Maintaining hepatology expertise • Relationships with ITU • 24/7 therapeutic endoscopy for bleeding • Repository for wider alcohol admissions? Quality and Productivity: Proven Case Study Alcohol Care Teams: reducing acute hospital admissions and improving quality of care Provided by: The British Society of Gastroenterology and Bolton NHS Foundation Trust Publication type: Quality and productivity example QIPP Evidence provides users with practical case studies that address the quality and productivity challenge in health and social care. All examples submitted are evaluated by NICE. This evaluation is based on the degree to which the initiative meets the QIPP criteria of savings, quality, evidence and implementability; each criterion is given a score which are then combined to give an overall score.r The overall score is used to identify the best examples, which ahn e then sow n or NHS Evidence as ‘eco mmended’. Our asseQIPPssment of the dforegree to walcoholhich this particular casecare study mee teamsts the criteria is represented in the evidence summary graphic below. Evidence summary Implementability Evidence of change Quality Savings 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Page 1 of 11 This document can be found online at: http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/qipp QIPP for alcohol care teams Challenges for the acute hospital Debate : is continuity now best delivered by a generalist ? Challenges for the system The new NHS – April 2013 Alcohol Related Admissions for Liverpool PCT (residents) 2002/03 to 2008/09 by Condition Group. -

Alcohol - a Global Problem

Gilmore BMC Medicine 2014, 12:209 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/12/209 Medicine for Global Health QUESTION AND ANSWER Open Access Video Q & A: Alcohol - a global problem. An interview with Ian Gilmore Ian Gilmore Abstract In this video Q & A, we talk to Ian Gilmore about the global burden of alcohol in terms of its scale, and its consequences in relation to non-communicable diseases and other illnesses. Sir Gilmore additionally discusses how the problem is being addressed, reviews the outcomes of recent initiatives and describes the challenge and future directions. Keywords: Alcohol, Global health, Addiction, Psychiatry Introduction Edited transcript Professor Sir Ian Gilmore is an honorary consultant (1) What is the scale of the alcohol problem? physician at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and The global scale of the alcohol problem is really quite re- holds an honorary chair at the University of Liverpool. markable. One cannot help feeling that if it was another After training in Cambridge, London and the USA, he infectious disease, like that caused by the Ebola virus, it moved to Liverpool as a consultant in 1980, where he would get a much higher priority. However, we are also has enjoyed working ever since. His specialty interest is comfortable with alcohol as it is much entrenched in liver disease. He is the immediate past-president of the our day-to-day lives such that it is very hard to persuade Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and is currently presi- people of the magnitude of the problem. Of all the con- dent of the British Society of Gastroenterology. -

Tuesday 7Th February 2012 Sir, We Congratulate Dr Sarah Wollaston

Tuesday 7th February 2012 Sir, We congratulate Dr Sarah Wollaston MP on achieving a parliamentary debate today on the crucial issue of the forthcoming alcohol strategy for England. We hope this will strengthen the resolve of the Secretary of State for Health to heed the evidence on the policies that will have a real impact in reducing the toll of alcohol‐related harm, especially on the health and wellbeing of young people. The Secretary of State emphasised the principle of concentrating on outcomes at the recent launch of a Public Health Framework for England which included details of his aspirations for reducing deaths from liver disease in the UK, 80% of which are alcohol‐related, and reducing alcohol‐related admissions to hospital, both of which continue to rise at alarming rates. It would be a betrayal of this principle to ignore the evidence on what works best on the outcomes of alcohol‐ related health and social harm ‐ strong action on price. Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the Republic of Ireland have all committed to introduce a minimum unit price for alcohol. If England were to join this ‘coalition of the willing’, Westminster could be in the vanguard of improving public health, rather than trailing behind, in implementing policies that tackle outcomes and are evidence‐based. We urge MPs to support Dr Wollaston in this important debate. Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, Chair, Alcohol Health Alliance Sir Richard Thompson, President, Royal College of Physicians Professor Lindsey Davies, President, Faculty of Public Health Professor Vivienne -

HSJ AWARDS 2007 WINNERS Sponsored by Acute Healthcare Organisation of the Year South Tees Hospital Trust

CONGRATULATIONS HSJ AWARDS 2007 WINNERS Sponsored by Acute Healthcare Organisation of the Year South Tees Hospital Trust Primary Care Organisation of the Year Wirral PCT Commissioning Chronic Disease Management Cornwall & Isles Of Scilly PCT Clinical Service Redesign Salford Royal Foundation Trust & Salford PCT Communications Newham University Hospital Trust Cost Effective Partnership Working Birmingham East And North PCT Good Corporate Citizenship Nottingham University Hospitals Trust Implementing NICE Guidance Oxleas Foundation Trust Improving Care with E-Technology NHS North West, Lancashire & South Cumbria Cardiac Network and BroomWell Healthwatch Improving Patient Access Bolton PCT Information-based Decision Making Leicestershire, Northamptonshire & Rutland Cancer Network Mental Health Innovation Oxfordshire PCT Patient-centred Care Leeds PCT Patient Safety Royal Wolverhampton Hospitals Trust Primary Care Innovation Bradford And Airedale Teaching PCT Recruitment and Retention NHS Tayside Reducing Health Inequalities East Lancashire PCT Skills Development The DESMOND Collaborative HSJ would like to thank everyone who entered the HSJ Awards 2007 and congratulates the winners and finalists WWW.HSJAWARDS.CO.UK HSJ AWARDS AWARDS HSJ EDITOR’S COMMENT Celebrating a record number of entries The shortlist for the HSJ Awards is and, for the acute and primary care packed with inspiring examples of organisation categories, visited the trusts healthcare at its best. on the shortlists to talk to managers, The record number of entries – well clinicians, staff and service users. The over 1,000 – demonstrates the King’s Fund was typically helpful in determination of staff to deliver letting us use its premises for meetings. excellence for their patients. This supplement is an invaluable guide Once again the judges were greatly to many of the best care innovations in impressed by the standard of entries. -

Board of Directors' Meeting Agenda Part I - 29.11.17 Committee, with Particular Focus on Key Risk Areas

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Wednesday 29 November 2017 Board Room, Aintree Lodge 10.15am AGENDA v = verbal d = document p = presentation © = consent agenda item Time Item Lead Reference PRELIMINARY BUSINESS 1. Apologies for Absence Chair B17-18/106 (v) To note the apologies for absence 2. Declarations of Interest Chair B17-18/107 (v) To receive declarations of interest in agenda items and / or any changes to the register of directors’ declarations of interest pursuant to Section 7 of Standing Orders 3. Minutes of the Previous Meeting (25 October 2017) Chair B17-18/108 (d) To approve the minutes of the Board of Directors, review the Board Action Log and discuss any matters arising 10.20 4. Patient, Staff and Volunteer Story Chief Nurse B17-18/109 (v) To note STRATEGIC CONTEXT 10.30 5. Chief Executive’s Report Chief Executive B17-18/110 (d) To note QUALITY & SAFETY 10.45 6. Quality Committee - Assurance Report (20 November Committee Chair B17-18/111 (d) 2017) To discuss and note the report and gain assurance from the Board of Directors' Meeting Agenda Part I - 29.11.17 Committee, with particular focus on key risk areas. 7. Safeguarding – Position Statement Chief Nurse B17-18/112 (d) To note 1/2 Page 1 of 129 Aintree University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Item Lead Reference FINANCE & PERFORMANCE 11.00 8. Finance & Performance Committee – Assurance Committee Chair B17-18/113 (d) Report (27 November 2017) To discuss and note the report and gain assurance from the Committee, with particular focus on the following reports and key risk areas: • Corporate Performance Report (October 2017) Chief Operating B17-18/114 (d) Officer • Finance Report (October 2017) Director of B17-18/115 (d) Finance 9. -

Section A: CPH to Complete Name: Ian Gilmore Job Title: Consultant Physician and Gastroenterologist, Royal Liverpool University

Section A: CPH to complete Name: Ian Gilmore Job title: Consultant Physician and Gastroenterologist, Royal Liverpool University Hospitals Honorary Professor at the Department of Medicine, University of Liverpool. Address: Chair, Liverpool Health Partners, Foundation Building, University of Liverpool, Guidance title: Disability, dementia and frailty in later life - mid-life approaches to prevention Committee: PHAC D Subject of expert Alcohol testimony: Evidence gaps or uncertainties: Relationship of alcohol consumption and the development and onset of dementia, disability and frailty Effectiveness of interventions to reduce alcohol consumption on the development and onset of dementia, disability and frailty in the general population How the mid-life population may differ from the general adult population Section B: Expert to complete Summary testimony: [Please use the space below to summarise your testimony in 250 – 1000 words – continue over page if necessary ] There is strong evidence on the impact of alcohol on disability and death. The WHO acknowledge alcohol as the biggest single risk factor globally for disability adjusted life years lost before the age of 60. This is because of the peak age of death / disability of alcohol-related deaths being 40-60, for example from violent deaths or cirrhosis. There are possible cardiovascular benefits of low-level consumption but these benefits accrue from 1-2 drinks a week, apply only to older people and are negated by ‘binge drinking’ at least once a month. There is no good evidence of differential effects of different drinks but spirits are more likely to be associated with heavier consumption. Patterns of drinking are important as well as total amount and binge drinking more strongly associated with violence and sudden death. -

Ulster Medical Society the SIR THOMAS & LADY EDITH DIXON

Ulster Medical Society trained nurse, so in a way he’s coming home tonight and his wife is already at home with some of her fam- THE SIR THOMAS & LADY EDITH DIXON LECTURE ily. So thank you for coming to Belfast in the midst of 11th February 2010 your schedule, we’re really looking forward to your ‘Alcohol—The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ talk. Professor Ian Gilmore Royal Liverpool Hospital Professor Ian Gilmore: Thank you very much, Professor Atkinson, for Professor Atkinson: that generous introduction and if you think that was Tonight is our Sir Thomas and Lady Edith Dixon stress coming up here two minutes late, I can say this, lecture and I’d like to welcome you all to that special some other things have been stressful around the last lecture, and perhaps I really don’t know very much few years. I haven’t done my homework as well as I about the Dixons, and I’m sure that some people over should about Sir Thomas and Lady Edith Dixon, but I tea afterwards will be able to educate us about the suspect there was some linen in there somewhere, Dixons, but the Dixons I think owned a lot of land and but perhaps I can be enlightened at teatime after- property around York Street in Belfast, but they were wards. So as Brew said we’re going to talk, not just very generous benefactors to Belfast. All of you prob- about the good, not just about the bad, but also about ably, except Ian here, and he maybe does know about the, unfortunately, sometimes ugly side of alcohol. -

Alcohol-Related Disease

13448 BSG - Alcohol Related Disease.qxd 11/3/10 11:39 Page 1 ALCOHOL-RELATED DISEASE Meeting the challenge of improved quality of care and better use of resources Lead Author KIERAN J. MORIARTY Co-Authors Paul Cassidy Kevin Moore David Dalton Lynn Owens Michael Farrell Jonathan Rhodes Ian Gilmore Don Shenker Christopher Hawkey Nick Sheron Francis Keaney A Joint Position Paper on behalf of the British Society of Gastroenterology Alcohol Health Alliance UK British Association for Study of the Liver The full report can be accessed at www.bsg.org.uk/clinical/general/publications.html 13448 BSG - Alcohol Related Disease.qxd 11/3/10 11:39 Page 2 Key Recommendations In a typical British District General Hospital, serving a Population of 250,000, there should be: 1 A multidisciplinary “Alcohol Care Team”, led by a 6 Multidisciplinary, person-centred care, which is Consultant, with dedicated sessions, who will also holistic, timely, non-judgmental and responsive to the collaborate with Public Health, Primary Care Trusts, needs and views of patients and their families. patient groups and key stakeholders to develop and implement a district alcohol strategy. 7 Integrated Alcohol Treatment Pathways between primary and secondary care, with progressive movement towards management in primary care. 2 Coordinated policies on detection and management of alcohol-use disorders in Accident and Emergency departments and Acute Medical Units, with access to Brief 8 Adequate provision of Consultants in gastroenterology Interventions and appropriate services within 24 hours of and hepatology to deliver specialist care to patients diagnosis. with alcohol-related liver disease. 9 National Indicators and Quality metrics, including 3 A 7-Day Alcohol Specialist Nurse Service and Alcohol alcohol-related admissions, readmissions and deaths, Link Workers’ Network, consisting of a lead healthcare against which hospitals should be audited. -

Disease Burden and Costs from Excess Alcohol Consumption, Obesity, and Viral Hepatitis: Fourth Report of the Lancet Standing Commission on Liver Disease in the UK

This is a repository copy of Disease burden and costs from excess alcohol consumption, obesity, and viral hepatitis: fourth report of the Lancet Standing Commission on Liver Disease in the UK. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126824/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Williams, R., Alexander, G., Armstrong, I. et al. (31 more authors) (2018) Disease burden and costs from excess alcohol consumption, obesity, and viral hepatitis: fourth report of the Lancet Standing Commission on Liver Disease in the UK. The Lancet, 391 (10125). pp. 1097-1107. ISSN 0140-6736 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32866-0 Article available under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Lancet Commission on Liver Disease in the UK IV: Increased disease burden and costs from excess alcohol consumption, obesity and viral hepatitis. -

RGS ONA Issue

MEET THE MEDICS ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: VIRGIN MARY HOSPITAL | CARL FIRTH | COUGH BOY! | MAKEEN BAROUDI ISSUE 108/AUTUMN 2020 ONA MAGAZINE ISSUE 108 AUTUMN 2020 ONA is the magazine for the Old Novocastrians’ Association All correspondence should be addressed to: The Development Office, Royal Grammar School, Eskdale Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4DX Telephone Development Office: 0191 212 8909 email: [email protected] Guest Editor: Dr Simon Barker Congratulations to current Y13 students Theo Hoult and Dominique Hewitson Editor: David F Goldwater (51-62) who have been appointed into the new roles of Old Novocastrians’ Association Sixth Form Ambassadors. Theo and Dominique will be responsible for The Editor reserves the right to edit, representing current students at a range of external events, including ONA alter or omit all submissions to the magazine. Copy may be carried over meetings, activities and dinners, and crucially, identifying and approaching Old to the next edition. The Editor’s Novos who could support current students, through talks and/or careers decision is final. advice. The Ambassadors will also be responsible for helping to shape ONA activities, so that they are interesting, relevant and of value to the Class of 2021 Contribute! We are always looking for and beyond. ONs can look forward to hearing more from the new ONA Sixth articles and news from Old Novos to Form Ambassadors in the next ONA Magazine. include in the magazine, so send your contributions, via email (if possible) to: [email protected] or by posting to the Development Office at the school. -

Joint Symposium on Mental Health and Addiction a Discussion, Exchange and Sharing of Perspectives

Joint symposium on mental health and addiction A discussion, exchange and sharing of perspectives November 2018 The Academy of Medical Sciences The Academy of Medical Sciences is the independent body in the UK representing the diversity of medical science. Our mission is to promote medical science and its translation into benefits for society. The Academy’s elected Fellows are the United Kingdom’s leading medical scientists from hospitals, academia, industry and the public service. We work with them to promote excellence, influence policy to improve health and wealth, nurture the next generation of medical researchers, link academia, industry and the NHS, seize international opportunities and encourage dialogue about the medical sciences. Académie nationale de médecine Since its foundation in 1820, the French Academy of Medicine (Académie nationale de médecine, ANM) has been, and remains, the French leading authority over health matters. The Academy provides the Government with independent, multidisciplinary, and up to date expertise covering medicine and public health as well as bioethics and innovations in medical sciences and biotechnologies. The Academy brings together physicians, surgeons, biologists, pharmacists, veterinarians and independent members (e.g. lawyers, sociologists) who are elected by their peers and confirmed by the President of the Republic. The Government may request advice from the Academy, and the Academy may provide unsolicited advices. The Academy’s sixteen Commissions audit experts in relevant fields, prepare reports or press releases that are submitted to and voted for by the Assembly. The Academy maintains and develops multiple international relationships through its Foundation, foreign members, federations and foreign missions. Today, younger more technical institutions have been created in regard to the diversity and complexity of specialized contemporary health issues. -

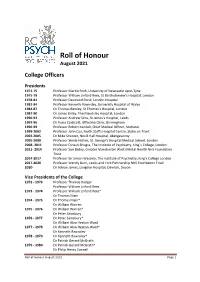

Roll of Honour August 2021

Roll of Honour August 2021 College Officers Presidents 1971-75 Professor Martin Roth, University of Newcastle upon Tyne 1975-78 Professor William Linford Rees, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London 1978-81 Professor Desmond Pond, London Hospital 1981-84 Professor Kenneth Rawnsley, University Hospital of Wales 1984-87 Dr Thomas Bewley, St Thomas’s Hospital, London 1987-90 Dr James Birley, The Maudsley Hospital, London 1990-93 Professor Andrew Sims, St James’s Hospital, Leeds 1993-96 Dr Fiona Caldicott, Uffculme Clinic, Birmingham 1996-99 Professor Robert Kendell, Chief Medical Officer, Scotland 1999-2002 Professor John Cox, North Staffs Hospital Centre, Stoke on Trent 2002-2005 Dr Mike Shooter, Nevill Hall Hospital, Abergavenny 2005-2008 Professor Sheila Hollins, St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London 2008- 2011 Professor Dinesh Bhugra, The Institute of Psychiatry, King`s College, London 2011- 2014 Professor Sue Bailey, Greater Manchester West Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust 2014-2017 Professor Sir Simon Wessely, The Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London 2017-2020 Professor Wendy Burn, Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust 2020- Dr Adrian James, Langdon Hospital, Dawlish, Devon Vice Presidents of the College 1972 - 1973 Professor Thomas Rodger Professor William Linford Rees 1973 - 1974 Professor William Linford Rees* Dr Thomas Main 1974 - 1975 Dr Thomas Main* Dr William Warren 1975 - 1976 Dr William Warren* Dr Peter Sainsbury 1976 - 1977 Dr Peter Sainsbury* Dr William Alan Heaton-Ward 1977 - 1978 Dr William Alan