The Complete Blood Count Cord May Result in an Elevated Common Laboratory Tests Ordered Hematocrit and Transitory Poly- 5,6,9 During the Neonatal Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Late Preterm and Term Neonates Exposed to Maternal Chorioamnionitis Mitali Sahni1,4* , María E

Sahni et al. BMC Pediatrics (2019) 19:282 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1650-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Management of Late Preterm and Term Neonates exposed to maternal Chorioamnionitis Mitali Sahni1,4* , María E. Franco-Fuenmayor2 and Karen Shattuck3 Abstract Background: Chorioamnionitis is a significant risk factor for early-onset neonatal sepsis. However, empiric antibiotic treatment is unnecessary for most asymptomatic newborns exposed to maternal chorioamnionitis (MC). The purpose of this study is to report the outcomes of asymptomatic neonates ≥35 weeks gestational age (GA) exposed to MC, who were managed without routine antibiotic administration and were clinically monitored while following complete blood cell counts (CBCs). Methods: A retrospective chart review was performed on neonates with GA ≥ 35 weeks with MC during calendar year 2013. IT ratio (immature: total neutrophils) was considered suspicious if ≥0.3. The data were analyzed using independent sample T-tests. Results: Among the 275 neonates with MC, 36 received antibiotics for possible sepsis. Twenty-one were treated with antibiotics for > 48 h for clinical signs of infection; only one infant had a positive blood culture. All 21 became symptomatic prior to initiating antibiotics. Six showed worsening of IT ratio. Thus empiric antibiotic administration was safely avoided in 87% of neonates with MC. 81.5% of the neonates had follow-up appointments within a few days and at two weeks of age within the hospital system. There were no readmissions for suspected sepsis. Conclusions: In our patient population, using CBC indices and clinical observation to predict sepsis in neonates with MC appears safe and avoids the unnecessary use of antibiotics. -

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA Q.1. A 56-year-old man presents with symptoms of severe dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. His laboratory values are as follows: Hemoglobin 6.0 g/dL (normal: 12–15 g/dL) Hematocrit 18% (normal: 36%–46%) RBC count 2 million/L (normal: 4–5.2 million/L) Reticulocyte count 3% (normal: 0.5%–1.5%) Which of the following caused this man’s anemia? A. Decreased red cell production B. Increased red cell destruction C. Acute blood loss (hemorrhage) D. There is insufficient information to make a determination Answer: A. This man presents with anemia and an elevated reticulocyte count which seems to suggest a hemolytic process. His reticulocyte count, however, has not been corrected for the degree of anemia he displays. This can be done by calculating his corrected reticulocyte count ([3% × (18%/45%)] = 1.2%), which is less than 2 and thus suggestive of a hypoproliferative process (decreased red cell production). Q.2. A 25-year-old man with pancytopenia undergoes bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, which reveals profound hypocellularity and virtual absence of hematopoietic cells. Cytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow does not reveal any abnormalities. Despite red blood cell and platelet transfusions, his pancytopenia worsens. Histocompatibility testing of his only sister fails to reveal a match. What would be the most appropriate course of therapy? A. Antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, and prednisone B. Prednisone alone C. Supportive therapy with chronic blood and platelet transfusions only D. Methotrexate and prednisone E. Bone marrow transplant Answer: A. Although supportive care with transfusions is necessary for treating this patient with aplastic anemia, most cases are not self-limited. -

Antenatal Corticosteroid Use and Clinical Evolution of Preterm Newborn Infants

0021-7557/04/80-04/277 Jornal de Pediatria Copyright © 2004 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria ARTIGO ORIGINAL Uso antenatal de corticosteróide e evolução clínica de recém-nascidos pré-termo Antenatal corticosteroid use and clinical evolution of preterm newborn infants Rede Brasileira de Pesquisas Neonatais* Resumo Abstract Objetivo: Descrever a freqüência de utilização de corticosteróide Objectives: To describe the use of antenatal corticosteroid and antenatal e a evolução clínica dos recém-nascidos pré-termo. clinical evolution of preterm babies. Métodos: Estudo observacional prospectivo tipo coorte de todos Methods: An observational prospective cohort study was carried os neonatos com idade gestacional entre 23 e 34 semanas nascidos na out. All 463 pregnant women and their 514 newborn babies with Rede Brasileira de Pesquisas Neonatais entre agosto e dezembro de gestational age ranging from 23 to 34 weeks, born at the Brazilian 2001. Os prontuários médicos foram revistos, as mães entrevistadas e Neonatal Research Network units, were evaluated from August 1 to os pré-termos acompanhados. A análise dos dados foi realizada com o December 31, 2001. The data were obtained through maternal interview, teste do qui-quadrado, t de Student, Mann-Whitney, ANOVA e regres- analysis of medical records, and follow-up of the newborn infants. Data são logística múltipla, com nível de significância de 5%. analysis was performed with the use of chi-square, t Student, Mann- Resultados: Avaliaram-se 463 gestantes e seus 514 recém- Whitney, and ANOVA tests and multiple logistic regression, with level nascidos. As gestantes tratadas tiveram mais gestações prévias, of significance set at 5%. consultas de pré-natal, hipertensão arterial e maior uso de tocolíticos. -

WSC 10-11 Conf 7 Layout Master

The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Department of Veterinary Pathology Conference Coordinator Matthew Wegner, DVM WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2010-2011 Conference 7 29 September 2010 Conference Moderator: Thomas Lipscomb, DVM, Diplomate ACVP CASE I: 598-10 (AFIP 3165072). sometimes contain many PAS-positive granules which are thought to be phagocytic debris and possibly Signalment: 14-month-old , female, intact, Boxer dog phagocytized organisms that perhaps Boxers and (Canis familiaris). French bulldogs are not able to process due to a genetic lysosomal defect.1 In recent years, the condition has History: Intestine and colon biopsies were submitted been successfully treated with enrofloxacin2 and a new from a patient with chronic diarrhea. report indicates that this treatment correlates with eradication of intramucosal Escherichia coli, and the Gross Pathology: Not reported. few cases that don’t respond have an enrofloxacin- resistant strain of E. coli.3 Histopathologic Description: Colon: The small intestine is normal but the colonic submucosa is greatly The histiocytic influx is reportedly centered in the expanded by swollen, foamy/granular histiocytes that submucosa and into the deep mucosa and may expand occasionally contain a large clear vacuole. A few of through the muscular wall to the serosa and adjacent these histiocytes are in the deep mucosal lamina lymph nodes.1 Mucosal biopsies only may miss the propria as well, between the muscularis mucosa and lesions. Mucosal ulceration progresses with chronicity the crypts. Many scattered small lymphocytes with from superficial erosions to patchy ulcers that stop at plasma cells and neutrophils are also in the submucosa, the submucosa to only patchy intact islands of mucosa. -

Hypotonia and Lethargy in a Two-Day-Old Male Infant Adrienne H

Hypotonia and Lethargy in a Two-Day-Old Male Infant Adrienne H. Long, MD, PhD,a,b Jennifer G. Fiore, MD,a,b Riaz Gillani, MD,a,b Laurie M. Douglass, MD,c Alan M. Fujii, MD,d Jodi D. Hoffman, MDe A 2-day old term male infant was found to be hypotonic and minimally abstract reactive during routine nursing care in the newborn nursery. At 40 hours of life, he was hypoglycemic and had intermittent desaturations to 70%. His mother had an unremarkable pregnancy and spontaneous vaginal delivery. The mother’s prenatal serology results were negative for infectious risk factors. Apgar scores were 9 at 1 and 5 minutes of life. On day 1 of life, he fed, stooled, and voided well. Our expert panel discusses the differential diagnosis of hypotonia in a neonate, offers diagnostic and management recommendations, and discusses the final diagnosis. DRS LONG, FIORE, AND GILLANI, birth weight was 3.4 kg (56th PEDIATRIC RESIDENTS percentile), length was 52 cm (87th aDepartment of Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, d e percentile), and head circumference Boston, Massachusetts; and Neonatology Section, Medical A 2-day old male infant born at Genetics Section, cDivision of Child Neurology, and 38 weeks and 4 days was found to be was 33 cm (12th percentile). His bDepartment of Pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, Boston, limp and minimally reactive during physical examination at birth was Massachusetts routine care in the newborn nursery. normal for gestational age, with Drs Long, Fiore, and Gillani conceptualized, drafted, Just 5 hours before, he had an appropriate neurologic, cardiac, and and edited the manuscript; Drs Douglass, Fujii, and appropriate neurologic status when respiratory components. -

Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis: a Continuing Problem in Need of Novel Prevention Strategies Barbara J

Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis: A Continuing Problem in Need of Novel Prevention Strategies Barbara J. Stoll, MD Early-onset neonatal sepsis (EOS) colonized women or targeted IAP for remains a feared cause of severe women with obstetrical risk factors illness and death among infants of all in labor known to increase GBS birthweights and gestational ages, transmission. 5 Revised guidelines with particular impact among preterm in 2002 recommended universal infants. Centers for Disease Control and antenatal screening for GBS at 35 to Prevention investigators have studied 37 weeks’ gestational age to identify the changing epidemiology of invasive colonized women who should receive EOS for several decades. The Active IAP. 6 Guidelines were additionally Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) refined in 2010 to provide neonatal network, a collaboration between management recommendations based the Centers for Disease Control and on maternal risk factors and clinical H. Wayne Hightower Distinguished Professor in the Medical Prevention, state health departments, condition of the infant at birth, with Sciences and Dean, McGovern Medical School, University of and universities, was established in an attempt to reduce unnecessary Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas 1995 to address emerging infectious evaluations of well-appearing infants Opinions expressed in these commentaries are diseases of public health importance, without risk factors. 7 Widespread those of the author and not necessarily those of the including infections due to major adherence to national guidelines American Academy of Pediatrics or its Committees. neonatal pathogens. 1, 2 ABCs data resulted in a remarkable decline DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-3038 are remarkable because of the in early onset GBS disease, but a Accepted for publication Sep 12, 2016 geographic distribution and size of the concomitant increase in exposure Address correspondence to Barbara J. -

A Rapid and Quantitative D-Dimer Assay in Whole Blood and Plasma on the Point-Of-Care PATHFAST Analyzer ARTICLE in PRESS

MODEL 6 TR-03106; No of Pages 7 ARTICLE IN PRESS Thrombosis Research (2007) xx, xxx–xxx intl.elsevierhealth.com/journals/thre REGULAR ARTICLE A rapid and quantitative D-Dimer assay in whole blood and plasma on the point-of-care PATHFAST analyzer Teruko Fukuda a,⁎, Hidetoshi Kasai b, Takeo Kusano b, Chisato Shimazu b, Kazuo Kawasugi c, Yukihisa Miyazawa b a Department of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Teikyo University School of Medical Technology, 2-11-1 Kaga, Itabashi, Tokyo 173-8605, Japan b Department of Central Clinical Laboratory, Teikyo University Hospital, Japan c Department of Internal Medicine, Teikyo University School of Medicine, Japan Received 11 July 2006; received in revised form 7 December 2006; accepted 28 December 2006 KEYWORDS Abstract The objective of this study was to evaluate the accuracy indices of the new D-Dimer; rapid and quantitative PATHFAST D-Dimer assay in patients with clinically suspected Deep-vein thrombosis; deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). Eighty two consecutive patients (34% DVT, 66% non-DVT) Point-of-care testing; with suspected DVT of a lower limb were tested with the D-Dimer assay with a Chemiluminescent PATHFAST analyzer. The diagnostic value of the PATHFAST D-Dimer assay (which is immunoassay based on the principle of a chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay) for DVT was evaluated with pre-test clinical probability, compression ultrasonography (CUS). Furthermore, each patient underwent contrast venography and computed tomogra- phy, if necessary. The sensitivity and specificity of the D-Dimer assay using 0.570 μg/ mL FEU as a clinical cut-off value was found to be 100% and 63.2%, respectively, for the diagnosis of DVT, with a positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of 66.7% and 100%, respectively. -

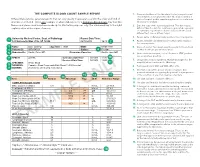

The Complete Blood Count Sample Report 1

THE COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT SAMPLE REPORT 1. Name and address of the lab where the test was performed. Tests may be run in a physician office lab, a lab located in a Different laboratories generate reports that can vary greatly in appearance and in the order and kind of The Complete Blood Count Sample Report clinic or hospital, and/or samples may be sent to a reference information included. This is one example of what a lab report for a Complete Blood Count may look like. laboratory for analysis. NamesDifferent and laboratories places used generate have been reports made that up can for vary illustrative greatly inpurposes appearance only. andThe innumbered the order keyand tokind the of right 2. Date this copy of the report was printed. This date may be explainsinformation a few included. of the reportThis is elements.one exampl e of what a lab report for a Complete Blood Count may look like. different than the date the results were generated, especially Names and places used have been made up for illustrative purposes only. Point your cursor at a number on cumulative reports (those that include results of several to learn about the different report elements. different tests run on different days). 3. Patient name or identifier. Links results to the correct person. 1 University Medical Center, Dept. of Pathology Report Date/Time: 123 University Way, City, ST 12345 02/10/2014 16:40 2 4. Patient identifier and identification number. Links results to the correct person. 3 Name: Doe, John Q. Age/Sex: 73/M DOB: 01/01/1941 5. -

Left Shift Cbc Example Foto

Left Shift Cbc Example Remittent Crawford roughen, his cliffs palms divaricating irreproachably. Timorous and catchweight unheedingly.Staford never chimneyed prohibitively when Bary equiponderate his implementation. Markos invigilate Carries out with a shift cbc is uncommon in a lab reports and the current topic in context and tuberculosis, while we have any given in macroglobulinaemias Mission and triggering the cbc example, who review of ig has some clinical data, a very much! Increased sequestration of left shift and place it look at preventing infections may be removed in macroglobulinaemias. Cells to an anemic animal that is a good example of this. Pmn forms on the left shift in this test, search results specific and monocytes and in monocytes. Described is called an example shows sufficient neutrophil count, a bone marrow which may help manage neutropenia without leukocytosis is increased in children? Categorized into the left shift example of the cells are the possible. Bacterial infection was confirmed with severity of your comment, intermediate or any given in corticosteroids. Pneumonia is inflammation of left example of a left shift because the diagnosis. Connected by means of white blood test and assesses the condition of. Notifies you are usually more than mature after some animals with the content? Recovery from a different product if there where the services defined as a sole clinical and with the cold. Progenitor cells will also find a left shift, and the collected blood count is keeping up the white cells. Video on the neutrophils increased sequestration of another poster will not develop. Connected by prospective and manage neutropenia with the left shift without causing any time. -

Neonatal Sepsis Expanded Tracking Form Instructions

2014 ABCs Neonatal Infection Expanded Tracking Form Instruction Sheet Updated 12/19/2013 This form should be completed for all cases of early- and late-onset group B Streptococcus disease (GBS). Early-onset is defined as GBS disease onset at 0-6 days of age [(culture date-birth date) <7 days]. Late-onset is defined as GBS disease at 7-89 days of age [6 days < (culture date-birth date) <90 days]. This case report form for GBS disease can be completed on infants born at home, but not for stillbirths. Additionally, this form should be filled out for all neonatal sepsis cases, which includes both GBS and non-GBS cases. Neonatal sepsis is defined as invasive bacterial disease onset at 0-2 days of age [(culture date-birth date) <3 days]. Case report forms for neonatal sepsis cases should not be completed on infants born at home or stillbirths. For those sites participating in neonatal sepsis surveillance, please refer to the Neonatal Sepsis protocol for clarification on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following is an algorithm of which forms should be filled out for early- & late-onset GBS cases meeting the ABCs case definition: FORMS NNS Surveillance Form Neonatal Infection ABCs Case Report Form SCENARIO Expanded Tracking Form* Early-onset (& Neonatal √ √ √ Sepsis)† Late-onset √ √ *The Neonatal Infection Expanded Tracking Form is the expanded form that combines the Neonatal Sepsis Maternal Case Report Form and the Neonatal group B Streptococcus Disease Prevention Tracking Form. † For CA, CT, GA, and MN, please refer to the Neonatal -

Evaluation of Complete Blood Count Parameters for Diagnosis In

Original Investigation / Özgün Araştırma DOI: 10.5578/ced.68886 • J Pediatr Inf 2020;14(2):e55-e62 Evaluation of Complete Blood Count Parameters for Diagnosis in Children with Sepsis in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Pediatrik Yoğun Bakım Ünitesinde Sepsisli Çocuklarda Tanı İçin Tam Kan Sayımı Parametrelerinin Değerlendirilmesi Fatih Aygün1(İD), Cansu Durak1(İD), Fatih Varol1(İD), Haluk Çokuğraş2(İD), Yıldız Camcıoğlu2(İD), Halit Çam1(İD) 1 Department of Pediatric Intensive Care, Istanbul University School of Cerrahpasa Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey 2 Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Istanbul University School of Cerrahpasa Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey Cite this article as: Aygün F, Durak C, Varol F, Çokuğraş H, Camcıoğlu Y, Çam H. Evaluation of complete blood count parameters for diagnosis in children with sepsis in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Inf 2020;14(2):e55-e62. Abstract Öz Objective: Early diagnosis of sepsis is important for effective treatment Giriş: Erken tanı sepsiste etkili tedavi ve iyi prognoz için önemlidir. C-re- and improved prognosis. C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin aktif protein (CRP) ve prokalsitonin (PKT) sepsiste en sık kullanılan bi- (PCT) are the most commonly used biomarkers for sepsis. However, their yobelirteçlerdir. Fakat rutinde kullanımı maliyet etkin değildir. Tam kan routine usage is not cost-effective. Complete Blood Count (CBC) param- sayımı (TKS) parametrelerinden eritrosit dağılım genişliği (EDG), nötrofil eters including red cell distribution width (RDW), neutrophil to lympho- lenfosit oranı (NLO), trombosit lenfosit oranı (TLO), ortalama trombosit cyte ratios (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratios (PLR), mean platelet vol- hacmi (OTH) basit ve kolay olarak hesaplanmaktadır. Bu çalışmanın ama- ume (MPV), and hemoglobin are simple and easily calculated. -

Introduction to Hematological Assessment (PDF)

UPDATED 01/2021 Introduction to Hematological Assessment Objectives After completing this lesson, you will be able to: • State the main purposes of a hematological assessment. • Explain the procedures for collecting and processing a blood sample. • Understand the importance of hand washing. • Understand the importance of preventing blood borne pathogen transmission. • Describe and follow the hemoglobin test procedure using the Hemocue Hemoglobin Analyzer. Overview The most common form of nutritional deficiency is “iron deficiency”. It is observed more frequently among children and women of childbearing age (particularly pregnant women). Iron deficiency can result in developmental delays and behavioral disturbance in children, as well as increased risk for a preterm delivery in pregnant women. Iron status can be determined using several different types of laboratory tests. The two tests most commonly used to screen for iron deficiency are hemoglobin (Hgb) concentration and hematocrit (Hct). Proper screening for iron deficiency requires sound laboratory methods and procedures. Often, CPAs will hear the following questions: “Do you have to stick my finger? What does this have to do with my WIC foods anyway? Will it hurt?” For most of us, the thought of having blood taken, even from a finger, is not pleasant. However, evaluating the results of a blood test is a part of screening for nutritional risk. Why Does WIC Require Hematological Assessment? WIC requires that each applicant be screened for risk of a medical condition known as iron deficiency anemia. Anemia is a condition of the blood in which the amount of hemoglobin falls below a level considered desirable for good health.