'Food and Me' Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Whole Grain Gluten-Free Quinoa, High Protein, Vegetable Flatbreads

Talwinder S Kahlon, IJFNR, 2019; 3:19 Research Article IJFNR (2019) 3:19 International Journal of Food and Nutrition Research (ISSN:2572-8784) Ancient whole grain gluten-free quinoa, high protein, vegetable flatbreads Talwinder S Kahlon, Roberto J Avena-Bustillos, Mei-Chen M Chiu and Ashwinder K Kahlon Western Regional Research Center, USDA-ARS, 800 Buchanan St., Albany, CA 94710 ABSTRACT The objective was to evaluate four kinds of ancient whole grain gluten- Abbreviations: Quinoa Peanut free Quinoa, high protein, vegetable, nutritious, tasty, health promoting Meal-Kale (QPK), bulk density (ρb), flatbreads. The flatbreads were Quinoa Peanut Meal Kale (QPK), true density (ρt), water activity (Aw) QPK-Onions, QPK-Garlic and QPK-Cilantro. Quinoa contains all the essential amino acids. Peanut Meal was utilized to formulate higher *Correspondence to Author: protein flatbreads and to add value to this low value farm byproduct. Talwinder S Kahlon Fresh green leafy vegetable kale was used with health promoting Western Regional Research Cen- potential as it binds bile acids. Onions, garlic and cilantro contain ter, USDA-ARS, 800 Buchanan St., healthful phytonutrients. The level of fresh onions, garlic and cilantro Albany, CA 94710 were determined by consensus of the laboratory personnel. Flatbread dough was prepared using 50-67 ml water per 100g as is ingredients. How to cite this article: The ingredients were Quinoa flour and Peanut Meal (39.4%) and Talwinder S Kahlon, Roberto J Av- fresh Kale (19.7%) as is basis. Onions, Garlic and Cilantro flatbreads ena-Bustillos, Mei-Chen M Chiu contained 28%, 7% and 28% of the respective ingredients. -

DOI: 10.18697/Ajfand.82.17090 13406 APPLICATION of a VALUE

Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2018; 18(2): 13406-13419 DOI: 10.18697/ajfand.82.17090 APPLICATION OF A VALUE CHAIN APPROACH TO UNDERSTANDING WHITE KENKEY PRODUCTION, VENDING AND CONSUMPTION PRACTICES IN THREE DISTRICTS OF GHANA Oduro-Yeboah C1*, Amoa-Awua W1, Saalia FK2, Bennett B3, Annan T1, Sakyi- Dawson E2 and G Anyebuno1 Charlotte Oduro-Yeboah *Corresponding Author email: [email protected] 1Food Research Institute, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Accra, Ghana 2Department of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Ghana. P.O. Box LG34, Legon 3Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime, Kent ME4 4TB, UK DOI: 10.18697/ajfand.82.17090 13406 ABSTRACT Traditional processing and street vending of foods is a vital activity in the informal sector of the Ghanaian economy and offers livelihood for a large number of traditional food processors. Kenkey is a fermented maize ‘dumpling’ produced by traditional food processors in Ghana. Ga and Fante kenkey have received research attention and there is a lot of scientific information on kenkey production. White kenkey produced from dehulled maize grains is a less known kind of kenkey. A survey was held in three districts of Ghana to study production, vending and consumption of white kenkey and to identify major bottlenecks related to production, which can be addressed in studies to re-package kenkey for a wider market. Questionnaires were designed for producers, vendors and consumers of white kenkey to collate information on Socio-cultural data, processing technologies, frequency of production and consumption, product shelf life, reasons for consumption and quality attributes important to consumers using proportional sampling. -

Impact of Food Processing on the Safety Assessment for Proteins Introduced Into Biotechnology-Derived Soybean and Corn Crops ⇑ B.G

Food and Chemical Toxicology 49 (2011) 711–721 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food and Chemical Toxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchemtox Review Impact of food processing on the safety assessment for proteins introduced into biotechnology-derived soybean and corn crops ⇑ B.G. Hammond a, , J.M. Jez b a Monsanto Company, Bldg C1N, 800 N. Lindbergh Blvd., St. Louis, Missouri 63167, USA b Washington University, Department of Biology, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1137, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA article info abstract Article history: The food safety assessment of new agricultural crop varieties developed through biotechnology includes Received 1 October 2010 evaluation of the proteins introduced to impart desired traits. Safety assessments can include dietary risk Accepted 10 December 2010 assessments similar to those performed for chemicals intentionally, or inadvertently added to foods. For Available online 16 December 2010 chemicals, it is assumed they are not degraded during processing of the crop into food fractions. For intro- duced proteins, the situation can be different. Proteins are highly dependent on physical forces in their Keywords: environment to maintain appropriate three-dimensional structure that supports functional activity. Food Biotech crops crops such as corn and soy are not consumed raw but are extensively processed into various food frac- Introduced proteins tions. During processing, proteins in corn and soy are subjected to harsh environmental conditions that Processing soy and corn Denaturation proteins drastically change the physical forces leading to denaturation and loss of protein function. These condi- Dietary exposure tions include thermal processing, changes in pH, reducing agents, mechanical shearing etc. -

Packed Lunches

Environmental Services A Guide to the Preparation of Packed Lunches Introduction Home prepared packed lunches now provide the midday meal for large numbers of school children and adults. Whether we consume these meals in winter or summer, the selection of food commodities, methods of preparation and storage are vitally important. The guidelines contained in this leaflet are designed to assist you in the safe and hygienic preparation of packed meals. Bacteria All foods will contain some germs (bacteria) but cooking normally kills them off. You don’t usually cook a sandwich, so it is important that the number of bacteria is kept to a minimum. Clearly some foods are more susceptible to bacterial problems than others. High-risk foods, i.e. those that are high in protein, can be perfect breeding grounds, particularly if there is sufficient moisture and warmth to enable bacteria to grow. The following are a few tips on how to buy, prepare and store safe food. Purchasing Food When you go shopping use a cool bag to carry home your high-risk foods, including frozen and chilled foods. If you can, try to purchase these food commodities last. Do not leave high-risk foods for long periods in a warm car. Ensure when buying food that you check the ‘use by’ or ‘best before’ dates. Remember you may be preparing food to eat at a later date and so you will need to bear this in mind. Always use food within the recommended dates. Immediately you arrive home, place all high-risk foods into the fridge/freezer units, having first separated raw and cooked foods to prevent cross-contamination from occurring. -

Back to School Nutrition

September 2016 Back to School Nutrition How to Ace Your Child ’ s Breakfast, Lunch, and Snacks throughout the School Year Back to School Nutrition: Kick-start Your Day with Breakfast! There’s a good reason breakfast has long been known as the most important meal of the day. Eating breakfast each morn- ing sets your body up for a successful day, giving you the energy and focus to do well in school and activities. Studies have shown the risks associated with kids skipping breakfast include: Higher rates of overweight and obesity Decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables Increased consumption of sugary beverages Increased consumption of fast food Benefits of eating breakfast include: Decreased likelihood of overeating at other meals or snacks Boost your metabolism and energy levels Improve memory and performance in school Quick and Easy Breakfast Ideas Whole wheat toast with peanut butter and banana Yogurt ( Greek or low-fat ) parfait layered with berries and granola Oatmeal topped with fruit and nuts Banana Bread Overnight Oats ( recipe on back ) Breakfast Burrito ( recipe on back ) Fruit and yogurt smoothies ( Peach Crisp smoothie recipe on back) Whole wheat English muffin topped with part-skim melted mozzarella cheese, sliced hard-boiled egg, and a slice of tomato Whole wheat frozen waffle topped with low-fat cream cheese and strawberries These recipes make for a delicious and healthy start to your child ’ s Recipe Box: morning. Each is full of fiber and provide long-lasting energy. In addi- Breakfast tion to great nutritional benefits, these recipes can be made ahead of time for easy morning grab-and-go. -

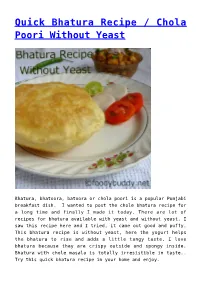

Quick Bhatura Recipe / Chola Poori Without Yeast

Quick Bhatura Recipe / Chola Poori Without Yeast Bhatura, bhatoora, batoora or chola poori is a popular Punjabi breakfast dish. I wanted to post the chole bhatura recipe for a long time and finally I made it today. There are lot of recipes for bhatura available with yeast and without yeast. I saw this recipe here and I tried, it came out good and puffy. This bhatura recipe is without yeast, here the yogurt helps the bhatura to rise and adds a little tangy taste. I love bhatura because they are crispy outside and spongy inside. Bhatura with chole masala is totally irresistible in taste.. Try this quick bhatura recipe in your home and enjoy. Ingredients for Quick Bhatura Recipe / Chola Poori Without Yeast Prep time : 4 hrs Cooking Time: 30 mins Serves :7 2 Cups of Maida (All Purpose Flour) 3 Tbsp of Sooji (Rava / Semolina) 4 Tbsp of Yogurt 1 Tbsp of Oil 1/2 Tsp of Sugar 1 Tsp of Baking Powder Vegetable Oil to deep fry Water as needed Method – Quick Bhatura Recipe / Chola Poori Without Yeast Mix all the ingredients in a bowl except oil, knead well and form a soft and smooth dough. Cover the bowl and keep it aside for 4 hrs to allow fermentation to take place. Knead the dough again and form it into lemon sized balls. Take one ball, roll into thick round shaped disc. Heat oil in a frying pan, once it is hot, turn the flame to medium, carefully slide the bhaturas in hot oil. After few seconds, press it with the back of the laddle, so that it puffs up. -

Roast Beef & Veggie Wraps

Roast Beef & KEY MESSAGES This recipe is an easy, nourishing lunch box solution for Veggie Wraps back-to-school. It also makes a fast and easy after school snack. No cooking required, flexibility on choice of ingredients and a short prep time make this recipe ideal for crazy schedules. Beef has nutrients, like high quality protein, iron, zinc and B-vitamins, that kids and adolescents need to stay strong and healthy. This is a No Cook recipe. Demo Check Lis GROCERY LIST EQUIPMENT LIST 12 oz. deli-style roast beef, 2 large cutting boards thinly sliced 1 serrated knife 10-15 MAKES 4 5 2 cups shredded broccoli 1 small spreader or MINUTES SERVINGS INGREDIENTS slaw rubber spatula 6 Tbsp. reduced-fat or fat- 2 white dinner plates free ranch dressing, divided 1 small clear glass bowl 1/2 cup reduced-fat or fat-free Nutrition information per serving (using Bottom Round): cream cheese, softened 1 medium clear glass bowl 511 Calories; 135 Calories from fat; 15 g Total Fat (5 g Saturated Fat; 6 g Monounsaturated Fat); 90 mg Cholesterol; 857 mg Sodium; 4 medium flour tortillas 1 white hero plate 52 g Total Carbohydrate; 6.2 g Dietary Fiber; 39 g Protein; 5.7 mg (8 to 10-inch diameter) 2 forks Iron; 12.3 mg Niacin; 0.4 mg Vitamin B6; 1.8 mcg Vitamin B12; 5.4 mg Zinc; 48.9 mcg Selenium. Measuring cups This recipe is an excellent source of Dietary Fiber, Protein, Iron, Measuring spoons Niacin, Vitamin B6, Vitamin B12, Zinc, and Selenium. -

Evaluation of Children's Lunch Box Contents by Photograph and Their

Journal of Food Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-0887 E-ISSN 1927-0895 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Evaluation of Children’s Lunch Box Contents by Photograph and Their Relationship with Mothers’ Concern Tomoko Osera1,2, Setsuko Tsutie3, Misako Kobayashi2 & Nobutaka Kurihara1 1Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, Graduate School of Life Science, Kobe Women’s University, Japan 2Takakuradai Kindergarten attached to Kobe Women’s University, Japan 3Clinical Nutrition Management, Graduate School of Life Science, Kobe Women’s University, Japan Correspondence: Nobutaka Kurihara, Graduate School of Life Science, Kobe Women’s University, 2-1 Higashisuma-Aoyama, Suma, Kobe, Japan. Tel: 81-78-737-2417. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 20, 2016 Accepted: December 18, 2016 Online Published: January 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/jfr.v6n1p78 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v6n1p78 Abstract Japanese kindergarten children usually bring lunch prepared by mothers. The contents may be influenced by mothers’ food concerns. We investigated the relationship between mothers’ concerns and children’s lunch box contents and preferences. Lunch boxes of 209 children were digitally photographed for 4 days at a private kindergarten in Japan. The amounts of rice, main dishes, vegetables and fruits in the lunch boxes were estimated by measuring the area occupied by each in the photograph; a questionnaire, including questions on mothers’ concerns and children’s preferences, was completed by mothers. Vegetable amounts in the lunch boxes were significantly related to mother’s concerns for their children’s lunch. Compared with estimated vegetable amounts below 11%, the amounts above 11% indicated that the number of foods disliked by children was lower, and mothers reported a higher rate of mindfulness towards vegetables and lower rate towards frozen food and believed that they prepared a balanced lunch. -

Catering Menu

725 W Golf Rd Hoffman Estates, IL 60169 INDIAHOUSECHICAGO.COM DEAR CUSTOMER, India House Catering, an award-winning catering service, has opened a brand new state-of-the-art catering kitchen in Hoffman Estates, IL. We are currently catering in Chicago, its suburbs, and various parts of the Midwest. With over 26 years of experience in catering, India House serves many types of occasions, including: Weddings, Receptions, Anniversaries, Birthdays, Professional Conferences, Reunions, and more! We are the only Indian caterer to specialize in: North Indian, South Indian, Gujarati, Swaminarayan/Jain, Indian Chinese, and Fusion Cusine. Our dedicated team helps ease the burden of planning an event with menu planning, vendor selection, and tastings. We are recognized at all major hotels in the Chicagoland area, such as Westin-Itasca, Marriot- Schaumburg, Renaissance-Schaumburg, Hilton- Chicago, Rosemont Convention Center, and many other locations. We cover complete food preparation and presentation and coordinate the details with venues so your catering your food is as seamless as possible. Our experienced team is looking forward to serving you from the planning stage through the day of the event so you and your guests can enjoy your event. We thoughtfully tailor our services to your preferences so each event is as magical as you can imagine it. Please give us the opportunity to cater your event. – Our Master Chefs can’t wait to share their food with you and your guests INDIA HOUSE APPETIZERS/ TANDOORI 1. Seafood 7. Tandoori Seafood 1. Shrimp 1. Shrimp 1. Shrimp Pakora 1. Shrimp Tikka 2. Shrimp Tawa Fry 2. Shrimp Hariyali Tikka 3. -

Lunch Eating Patterns During Working Hours and Their Social and Work-Related Determinants : Study of Finnish Employees

Susanna Raulio Susanna Raulio Lunch eating patterns during working hours Susanna Raulio and their social and RESEARCH Lunch eating patterns during working hours RESEARCH and their social and work-related determinants work-related determinants Study of Finnish employees Study of Finnish employees and their social work-related determinants Lunch eating patterns during working hours Work has a central role in the lives of big share of adult Finns and meals they eat during the workday comprise an important factor in their nutrition, health, and well-being. This study examines the contribution of various socio- demographic, socioeconomic, and work-related factors to the lunch eating patterns of Finnish employees during the working day and how lunch eating patterns influence dietary intake. This thesis utilizes three different population-based cross-sectional surveys: Health Behaviour and Health among the Finnish Adult Population survey, the National Findiet 2002 Study and Work and Health in Finland. The frequency of worksite canteen use has been quite stable for over two decades in Finland. A small decreasing trend can be seen in all socioeconomic groups. During the whole period studied, those with more years of education ate at worksite canteens more often than the others. A worksite canteen was more commonly available to employees with higher education and occupational status and to those working at larger workplaces. Employees who ate at a worksite canteen consumed more vegetables and vegetable and fish dishes at lunch than did those who -

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI COLLEGE OF SCIENCE FACULTY OF BIOSCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SHELF LIFE STUDIES OF VACUUM PACKAGED ‘FANTI-KENKEY’ BY JAPHET ASANTE NOVEMBER, 2018 SHELF LIFE STUDIES OF VACUUM PACKAGED FANTI-KENKEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF FOOD QUALITY MANAGEMENT IN FOOD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY (MSC. FOOD QUALITY MANAGEMENT) BY JAPHET ASANTE (BSc. POSTHARVEST TECHNOLOGY) NOVEMBER, 2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the effort of my own hardworking except for references to other people‟s work which have been truly acknowledged, this thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, is the result of my own findings and has not been presented for any degree elsewhere. ASANTE JAPHET (PG1048617) ……………………… ……………… Student ID Signature Date Certified by Dr. (Mrs.) Faustina Dufie Wireko – Manu ……………………. ………………. Supervisor Signature Date Certified by Dr. (Mrs.) Faustina Dufie Wireko – Manu ……………………… ………………. Head of Department Signature Date ii ACKNOWDGEMENT My first and foremost thanks and praise go to the Almighty God, who gave me wisdom, direction Protection, Travelling mercies and strength throughout my postgraduate studies. I would like to express my sincere appreciation and gratitude to my lecturers and supervisor, Dr. (Mrs.) Faustina Dufie Wireko-Manu who despite her busy schedule, supervised my work and whose constructive criticisms, useful comments and guidance made this work a success. I would also want to thank Benjamin Nyarko,Yaw Gyamfi,Alexandra Ohenewaa Kwakye and Jemima,Owusuah Asante for their immense guidelines and contributions to make this thesis a success. -

University of Ghana, Legon GHANA LEAP 1000 IMPACT EVALUATION E

Institute of Statistical, Social & Economic Research (ISSER), University of Ghana, Legon GHANA LEAP 1000 IMPACT EVALUATION ENDLINE SURVEY HOUSEHOLD INSTRUMENT 2017 1 COVER SHEET ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 FUTURE CONTACT INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION A1: HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION CONFIRMATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION A2: NEW HOUSEHOLD MEMBER ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 SECTION 1: HOUSEHOLD ROSTER .................................................................................................................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. SECTION 2: EDUCATION OF ALL HOUSEHOLD MEMBERS AGED 3 YEARS OR OLDER ........................................................................................................................ 9 SECTION 3: HEALTH OF ALL HOUSEHOLD