Why Bank One Left Chicago: One Piece in a Bigger Puzzle, Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Bay Area Companies That Match Employee Donations*

BAY AREA COMPANIES THAT MATCH EMPLOYEE DONATIONS* To our knowledge, the following local companies offer a matching gift when their employees make a personal donation to a nonprofit organization. This means that your employer may be willing to match all or part of your donation amount with its own donation. A “matching gift” is a donation made by a corporation or foundation on behalf of an employee that matches that employee’s contribution to a nonprofit organization. This can double, triple, or even quadruple your contribution! Our partial list of Bay Area corporations and foundations with matching gift programs is below. Contact your Human Resources department for information about your company’s program. If you find that your unlisted employer does offer a matching gift program, please let us know so that we can add them to our list. Thank you! *Our list was compiled from other lists found online and may not be comprehensive or up to date, so please check with your employer. Your employer will provide you with all the information needed to process your matching gift. 3Com Corporation AOL/Time Warner 3M Foundation AON Foundation Abbott Laboratories Fund Applera Corporation AC Vroman Inc. Applied Materials Accenture Aramark Corp. ACE INA Foundation Archer-Daniels-Midland Company Acrometal Companies Inc. Archie and Bertha Walker Foundation Acuson ARCO Foundation Adaptec, Inc. Argonaut Insurance Group ADC Telecommunications Arkwright Foundation, Inc. Addison Wesley Longman Arthur J. Gallagher Foundation Adobe Systems, Inc. Aspect Communications Corp. ADP Foundation Aspect Global Giving Program Advanced Fibre Communications Aspect Telecommunications Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) AT&T Foundation Advantis ATC AES Corporation ATK Sporting Equipment Aetna Foundation, Inc. -

Chronology, 1963–89

Chronology, 1963–89 This chronology covers key political and economic developments in the quarter century that saw the transformation of the Euromarkets into the world’s foremost financial markets. It also identifies milestones in the evolu- tion of Orion; transactions mentioned are those which were the first or the largest of their type or otherwise noteworthy. The tables and graphs present key financial and economic data of the era. Details of Orion’s financial his- tory are to be found in Appendix IV. Abbreviations: Chase (Chase Manhattan Bank), Royal (Royal Bank of Canada), NatPro (National Provincial Bank), Westminster (Westminster Bank), NatWest (National Westminster Bank), WestLB (Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale), Mitsubishi (Mitsubishi Bank) and Orion (for Orion Bank, Orion Termbank, Orion Royal Bank and subsidiaries). Under Orion financings: ‘loans’ are syndicated loans, NIFs, RUFs etc.; ‘bonds’ are public issues, private placements, FRNs, FRCDs and other secu- rities, lead managed, co-managed, managed or advised by Orion. New loan transactions and new bond transactions are intended to show the range of Orion’s client base and refer to clients not previously mentioned. The word ‘subsequently’ in brackets indicates subsequent transactions of the same type and for the same client. Transaction amounts expressed in US dollars some- times include non-dollar transactions, converted at the prevailing rates of exchange. 1963 Global events Feb Canadian Conservative government falls. Apr Lester Pearson Premier. Mar China and Pakistan settle border dispute. May Jomo Kenyatta Premier of Kenya. Organization of African Unity formed, after widespread decolonization. Jun Election of Pope Paul VI. Aug Test Ban Take Your Partners Treaty. -

H.2 Actions of the Board, Its Staff, and The

ANNOUNCEMENT H.2, 1993, No. 48 Actions of the Board, its Staff, and BOARD OF GOVERNORS the Federal Reserve Banks; OF THE Applications and Reports Received FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM During the Week Ending November 27, 1993 ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS BANK HOLDING COMPANIFg Chemical Banking Corporation, New York, New York -- to engage in underwriting and dealing in, to a limited extent, all types of bank-ineligible equity securities through Chemical Securities Inc. Approved, November 24, 1993. Chemical Banking Corporation, New York, New York -- request for subsidiary banks and broker dealer subsidiaries of those banks to act as a riskless principal or broker for customers in buying and selling bank-eligible securities that Chemical*s section 20 subsidiary deals in or underwrites. Approved, November 24, 1993. First Alabama Bancshares, Inc., Birmingham, Alabama - - to acquire Secor Bank, F.S.B. Approved, November 22, 1993. BANK MERGERS First Alabama Bank, Birmingham, Alabama — to acquire certain assets and assume certain liabilities of Secor Bank, F.S.B. Approved, November 22, 1993. BOARD OPERATIONS Budget for 1994. Approved, November 24, 1993. Office of Inspector General -- budget for 1994. Approved, November 24, 1993. ENFORCEMENT Farmers and Merchants BanK or Long Deacn, Long Beach, California -- written agreement dated November 10, 1993, with the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Announced, November 22, 1993. First Tampa Bancorporation of Florida, Inc., Tampa, Florida -- written agreement dated November 8, 1993, with the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. Announced, November 22, 1993. Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis H.2 NOVEMBER 22, 1993 TO NOVEMBER 26, 1993 PAGE 2 ACTIONS TAKEN BY THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS REGULATIONS AND POLICIES Regulation DD, Truth in Savings -- proposed changes concerning calculation of the annual percentage yields for certain deposits (Docket R-0812). -

To the Stockholders of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank One

To the stockholders of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank One Corporation A MERGER PROPOSAL Ì YOUR VOTE IS VERY IMPORTANT The boards of directors of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank One Corporation have approved an agreement to merge our two companies. The proposed merger will create one of the largest and most globally diversiÑed Ñnancial services companies in the world and will establish the second-largest banking company in the United States based on total assets. The combined company, which will retain the J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. name, will have assets of $1.1 trillion, a strong capital base, 2,300 branches in 17 states and top-tier positions in retail banking and lending, credit cards, investment banking, asset management, private banking, treasury and securities services, middle-market and private equity. We believe the combined company will be well-positioned to achieve strong and stable Ñnancial performance and increase stockholder value through its balanced business mix, greater scale and enhanced eÇciencies and competitiveness. In the proposed merger, Bank One will merge into JPMorgan Chase, and Bank One common stockholders will receive 1.32 shares of JPMorgan Chase common stock for each share of Bank One common stock they own. This exchange ratio is Ñxed and will not be adjusted to reÖect stock price changes prior to the closing. Based on the closing price of JPMorgan Chase's common stock on the New York Stock Exchange (trading symbol ""JPM'') on January 13, 2004, the last trading day before public announcement of the merger, the 1.32 exchange ratio represented approximately $51.35 in value for each share of Bank One common stock. -

Corporate Decision #97-36 June 1997

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Washington, D.C. 20219 Corporate Decision #97-36 June 1997 DECISION OF THE OFFICE OF THE COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY ON THE APPLICATION TO MERGE COLORADO NATIONAL BANK, DENVER, COLORADO, COLORADO NATIONAL BANK ASPEN, ASPEN, COLORADO, FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, OMAHA, NEBRASKA, FIRST BANK OF SOUTH DAKOTA (NATIONAL ASSOCIATION), SIOUX FALLS, SOUTH DAKOTA, FIRST BANK (NATIONAL ASSOCIATION), MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN, FIRST INTERIM BANK OF DES MOINES, N.A., DES MOINES, IOWA, AND FIRST INTERIM BANK OF CASPER, N.A., CASPER, WYOMING, WITH AND INTO FIRST BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA June 1, 1997 ___________________________________________________________________________ __ I. INTRODUCTION On March 17, 1997, First Bank National Association, Minneapolis, Minnesota ("FBNA") filed an Application with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ("OCC") for approval to merge affiliated national banks located in other states into FBNA under FBNA’s charter and title, pursuant to 12 U.S.C. §§ 215a-1, 1828(c) & 1831u(a) (the "Merger Application"). The merger is structured as a single merger transaction with multiple affiliated target institutions. The affiliated banks are: Colorado National Bank, Denver, Colorado ("Colorado NB"), Colorado National Bank Aspen, Aspen, Colorado ("Aspen NB"), First Bank National Association, Chicago, Illinois ("FB Chicago"), First Bank National Association, Omaha, Nebraska ("FB Omaha"), First Bank of South Dakota (National Association), Sioux Falls, South Dakota ("FB South Dakota"), First Bank (National Association), Milwaukee, Wisconsin ("FB Milwaukee"), First Interim Bank of Des Moines, National Association, Des Moines, Iowa ("FB Des Moines"), and First Interim Bank of Casper, National Association, Casper, Wyoming ("FB Casper"). -

U.S. Bancorp (USB)

Strategic Report for U.S. Bancorp Ah Sung Yang Karen Bonner Andrew Dialynas April 14, 2010 US Bancorp Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 3 Company Overview ........................................................................................................ 5 Company History ................................................................................................... 5 Business Model ..................................................................................................... 8 Competitive analysis .................................................................................................... 10 Industry Overview ................................................................................................ 10 Porter’s Five Forces Analysis .............................................................................. 11 Competitive Rivalry......................................................................................... 11 Entry and Exit ................................................................................................. 12 Supplier Power ............................................................................................... 13 Buyer power ................................................................................................... 14 Substitutes and Complements ........................................................................ 15 Financial Analysis ....................................................................................................... -

JP Morgan Chase Sofya Frantslikh Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 3-14-2005 Mergers and Acquisitions, Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase Sofya Frantslikh Pace University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Corporate Finance Commons Recommended Citation Frantslikh, Sofya, "Mergers and Acquisitions, Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase" (2005). Honors College Theses. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thesis Mergers and Acquisitions Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase By: Sofya Frantslikh 1 Dedicated to: My grandmother, who made it her life time calling to educate people and in this way, make their world better, and especially mine. 2 Table of Contents 1) Abstract . .p.4 2) Introduction . .p.5 3) Mergers and Acquisitions Overview . p.6 4) Case In Point: JP Morgan Chase . .p.24 5) Conclusion . .p.40 6) Appendix (graphs, stats, etc.) . .p.43 7) References . .p.71 8) Annual Reports for 2002, 2003 of JP Morgan Chase* *The annual reports can be found at http://www.shareholder.com/jpmorganchase/annual.cfm) 3 Abstract Mergers and acquisitions have become the most frequently used methods of growth for companies in the twenty first century. They present a company with a potentially larger market share and open it u p to a more diversified market. A merger is considered to be successful, if it increases the acquiring firm’s value; m ost mergers have actually been known to benefit both competition and consumers by allowing firms to operate more efficiently. -

In Re: Fleetboston Financial Corporation Securities Litigation 02-CV

Case 2:02-cv-04561-GEB-MCA Document 28 Filed 04/23/2004 Page 1 of 36 NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Civ. No. 02-4561 (WGB) IN RE FLEETBOSTON FINANCIAL CORPORATION SECURITIES LITIGATION O P I N I O N APPEARANCES: Gary S. Graifman, Esq. Benjamin Benson, Esq. KANTROWITZ, GOLDHAMER & GRAIFMAN 210 Summit Avenue Montvale, New Jersey 07645 Liaison Counsel for Plaintiffs Samuel H. Rudman, Esq. CAULEY GELLER BOWMAN & COATES, LLP 200 Broadhollow Road, Suite 406 Melville, NY 11747 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Joseph H. Weiss, Esq. WEISS & YOURMAN 551 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1600 New York, New York 10176 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs Jules Brody, Esq. Howard T. Longman, Esq. STULL, STULL & BRODY 6 East 45 th Street New York, New York 10017 Co-Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs 1 Case 2:02-cv-04561-GEB-MCA Document 28 Filed 04/23/2004 Page 2 of 36 David M. Meisels, Esq. HERRICK, FEINSTEIN LLP 2 Penn Plaza Newark, NJ 07105-2245 Mitchell Lowenthal, Esq. Jeffrey Rosenthal, Esq. CLEARY, GOTTLIEB, STEEN & HAMILTON One Liberty Plaza New York, NY 10006 Attorneys for Defendants BASSLER, DISTRICT JUDGE: This is a putative securities class action brought on behalf of all persons or entities except Defendants, who exchanged shares of Summit Bancorp (“Summit”) common stock for shares of FleetBoston Financial Corporation (“FBF”) common stock in connection with the merger between FBF and Summit. Defendants FBF and the individual Defendants 1 (collectively “Defendants”) move to dismiss Plaintiffs’ Consolidated Amended Complaint (“the Amended Complaint”) pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure Rule 12(b)(6). -

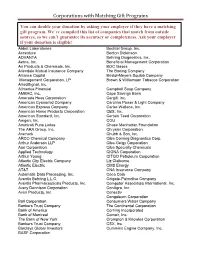

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs

Corporations with Matching Gift Programs You can double your donation by asking your employer if they have a matching gift program. We’ve compiled this list of companies that match from outside sources, so we can’t guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Ask your employer if your donation is eligible! Abbot Laboratories Bechtel Group, Inc. Accenture Becton Dickinson ADVANTA Behring Diagnostics, Inc. Aetna, Inc. Beneficial Management Corporation Air Products & Chemicals, Inc. BOC Gases Allendale Mutual Insurance Company The Boeing Company Alliance Capital Bristol-Meyers Squibb Company Management Corporation, LP Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation AlliedSignal, Inc. Allmerica Financial Campbell Soup Company AMBAC, Inc. Cape Savings Bank Amerada Hess Corporation Cargill, Inc. American Cyanamid Company Carolina Power & Light Company American Express Company Carter-Wallace, Inc. American Home Products Corporation CBS, Inc. American Standard, Inc. Certain Teed Corporation Amgen, Inc. CGU Ammirati Puris Lintas Chase Manhattan Foundation The ARA Group, Inc. Chrysler Corporation Aramark Chubb & Son, Inc. ARCO Chemical Company Ciba Corning Diagnostics Corp. Arthur Anderson LLP Ciba-Geigy Corporation Aon Corporation Ciba Specialty Chemicals Applied Technology CIGNA Corporation Arthur Young CITGO Petroleum Corporation Atlantic City Electric Company Liz Claiborne Atlantic Electric CMS Energy AT&T CNA Insurance Company Automatic Data Processing, Inc. Coca Cola Aventis Behring L.L.C. Colgate-Palmolive Company Aventis Pharmaceuticals Products, Inc. Computer Associates International, Inc. Avery Dennison Corporation ConAgra, Inc. Avon Products, Inc. Conectiv Congoleum Corporation Ball Corporation Consumers Water Company Bankers Trust Company The Continental Corporation Bank of America Corning Incorporated Bank of Montreal Comair, Inc. The Bank of New York Crompton & Knowles Corporation Bankers Trust Company CSX, Inc. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 227 / Monday, November 27, 1995 / Notices 58363

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 227 / Monday, November 27, 1995 / Notices 58363 Y (12 CFR 225.21(a)) to commence or to 2. Progressive Growth Corp., Gaylord, company or to acquire voting securities engage de novo, either directly or Minnesota; to engage de novo through of a bank or bank holding company. The through a subsidiary, in a nonbanking its subsidiary, Progressive Technologies, listed companies have also applied activity that is listed in § 225.25 of Inc., Gaylord Minnesota, in data under § 225.23(a)(2) of Regulation Y (12 Regulation Y as closely related to warehousing, computer network CFR 225.23(a)(2)) for the Board's banking and permissible for bank integration services, communications approval under section 4(c)(8) of the holding companies. Unless otherwise services related to the transmission of Bank Holding Company Act (12 U.S.C. noted, such activities will be conducted economic and financial data, database 1843(c)(8)) and § 225.21(a) of Regulation throughout the United States. management services, and other data Y (12 CFR 225.21(a)) to acquire or Each application is available for processing services, pursuant to § control voting securities or assets of a immediate inspection at the Federal 225.25(b)(7) of the Board's Regulation Y. company engaged in a nonbanking Reserve Bank indicated. Once the C. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas activity that is listed in § 225.25 of application has been accepted for City (John E. Yorke, Senior Vice Regulation Y as closely related to processing, it will also be available for President) 925 Grand Avenue, Kansas banking and permissible for bank inspection at the offices of the Board of City, Missouri 64198: holding companies, or to engage in such Governors. -

Federal Reserve Bulletin December 1991

VOLUME 77 • NUMBER 12 • DECEMBER 1991 FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM, WASHINGTON, D.C. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Joseph R. Coyne, Chairman • S. David Frost • Griffith L. Garwood • Donald L. Kohn • J. Virgil Mattingly, Jr. • Michael J. Prell • Edwin M. Truman The Federal Reserve Bulletin is issued monthly under the direction of the staff publications committee. This committee is responsible for opinions expressed except in official statements and signed articles. It is assisted by the Economic Editing Section headed by S. Ellen Dykes, the Graphics Center under the direction of Peter G. Thomas, and Publications Services supervised by Linda C. Kyles. Table of Contents 967 AN UPDATE ON THE FARM ECONOMY believes that more sweeping changes are premature at this time, before the Subcommit- The latter part of the 1980s was a relatively tee on Telecommunications and Finance of the prosperous time for farmers. In 1990, how- House Committee on Energy and Commerce, ever, prices fell sharply in some parts of the October 25, 1991. farm economy, and in 1991, weakness in the sector has become more widespread. A soften- ing of the farm economy perhaps rekindles 992 ANNOUNCEMENTS memories of the farm financial stresses of the Final modifications of risk-based capital first half of the 1980s. But overall, imbalances guidelines. in the sector are far less pronounced than those of the early 1980s, and its vulnerability to Fee schedules of the Federal Reserve Banks financial setback has been reduced. for 1992. Publication of the revised Lists of Marginable 980 INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION AND CAPACITY OTC Stocks and of Foreign Margin Stocks. -

School of Economics & Business Administration Master of Science in Management “MERGERS and ACQUISITIONS in the GREEK BANKI

School of Economics & Business Administration Master of Science in Management “MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS IN THE GREEK BANKING SECTOR.” Panolis Dimitrios 1102100134 Teti Kondyliana Iliana 1102100002 30th September 2010 Acknowledgements We would like to thank our families for their continuous economic and psychological support and our colleagues in EFG Eurobank Ergasias Bank and Marfin Egnatia Bank for their noteworthy contribution to our research. Last but not least, we would like to thank our academic advisor Dr. Lida Kyrgidou, for her significant assistance and contribution. Panolis Dimitrios Teti Kondyliana Iliana ii Abstract M&As is a phenomenon that first appeared in the beginning of the 20th century, increased during the first decade of the 21st century and is expected to expand in the foreseeable future. The current global crisis is one of the most determining factors affecting M&As‟ expansion. The scope of this dissertation is to examine the M&As that occurred in the Greek banking context, focusing primarily on the managerial dimension associated with the phenomenon, taking employees‟ perspective with regard to M&As into consideration. Two of the largest banks in Greece, EFG EUROBANK ERGASIAS and MARFIN EGNATIA BANK, which have both experienced M&As, serve as the platform for the current study. Our results generate important theoretical and managerial implications and contribute to the applicability of the phenomenon, while providing insight with regard to M&As‟ future within the next years. Keywords: Mergers &Acquisitions, Greek banking sector iii Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Literature Review .......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Streams of Research in M&As ................................................................................ 4 2.1.1 The Effect of M&As on banks‟ performance ..................................................