Finding Artwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franklin Carmichael's Representation of The

TRANSCENDENTAL NATURE AND CANADIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY: FRANKLIN CARMICHAEL’S REPRESENTATION OF THE CANADIAN LANDSCAPE by NICOLE MARIE MCKOWEN Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Fine Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 TRANSCENDENTAL NATURE AND CANADIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY: FRANKLIN CARMICHAEL’S REPRESENTATION OF THE CANADIAN LANDSCAPE Thesis Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Frances Colpitt, Deedie Rose Chair of Art History ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Meredith Munson, Lecturer, Art History at University of Texas, Arlington ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Butler, Associate Dean for the College of Fine Arts Date ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my committee chair Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite and my committee members Dr. Frances Colpitt and Dr. Meredith Munson for their time and guidance throughout the writing of this thesis. I am also grateful to all of the faculty of the Art History Division of the School of Art at Texas Christian University, Dr. Babette Bohn, Dr. Lori Diel, and Dr. Jessica Fripp, for their support of my academic pursuits. I extend my warmest thanks to Catharine Mastin for her support of my research endeavors and gratefully recognize archivist Philip Dombowsky at the National Gallery of Canada, archivist Linda Morita and registrar Janine Butler at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, and the archivists at the Library and Archives Canada for their enthusiastic aid throughout my research process. Finally, I am indebted to my husband and family, my champions, for their unwavering love and encouragement. -

Art in 2017: a View from Turtle Island – Canadian Art

1/18/2018 Art in 2017: A View from Turtle Island – Canadian Art FEATURES / / Art in 2017: A View from Turtle Island Strong exhibitions in Winnipeg, Kitchener-Waterloo and Toronto highlight an Indigenous critic’s year-end bests DECEMBER 28, 2017 BY LINDSAY NIXON Mike MacDonald, Seven Sisters, 1989. Video installation, running time: 7 videos, 55 minutes each. Courtesy of Vtape, Toronto © Mike MacDonald. Installed at “Carry Forward” at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. Image courtesy of KWAG. Photo: Robert McNair. The year was an exciting one for Indigenous art in so-called Canada—likely somewhat propelled by the Canada Council’s newly created funding stream for Indigenous art. I can’t think of another period—outside of 1992, the 350th anniversary of the birth of Montreal and 500 years since Columbus did not discover America—when Indigenous art was this dynamic. This year was host to a diverse group of new voices for Indigenous art, an array of artists and curators who established themselves as strong leaders and key gures in this new wave of contemporary Indigenous art. Joi https://canadianart.ca/features/art-in-2017-carrying-forward/ 1/13 1/18/2018 Art in 2017: A View from Turtle Island – Canadian Art T. Arcand, Dayna Danger, Asinnajaq, Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter, Becca Taylor, Tsēma Igharas, Jeneen Frei Njootli and Lacie Buring come to mind, to name only a few. Is what Tanya Harnett told me true—are we witnessing the emergence of a seventh wave in Indigenous art within so-called Canada? Whatever this moment is, it’s adamantly feminist; run by women, gender variant and sexually diverse peoples; and entrenched in values of care and reciprocity. -

University of Toronto Artists

2010 2010 www.art.utoronto.ca UNIVERSITY OF ARTISTS ESSAYS TORONTO Kathleen Boetto Michelle Jacques MVS Programme Rebecca Diederichs Vladimir Spicanovic Graduating Exhibition Bogdan Luca Alison Syme MEDIA (RE)VISION: HOW TO GET THERE FROM HERE The 2010 Graduating Exhibition of: Rebecca Diederichs Kathleen Boetto Bogdan Luca MEDIA (RE)VISION: UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO MVS (Masters of Visual Studies) Programme in Studio Art HOW TO GET THERE FROM HERE relevant to contemporary artists and curators Associate Curator Contemporary Art at the Art in discussing his recent work in the production Gallery of Ontario, who considers the work of of “Knossos as a memory object”. Independent Rebecca Diederichs; Vladimir Spicanovic, Dean, curator Nancy Campbell revealed her long- Faculty of Art, Ontario College of Art & Design, LISA STEELE standing involvement with artists working in who elucidates the form and the content Canada’s far North. Jean Baptiste Joly, Director of Bogdan Luca’s painting practice; and our of the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart own Art History colleague Alison Syme who spoke about the origins of contemporary art decodes the mediaized imagery of Kathleen “So, with his word “researches” Herodotus mobilizing desire and response as easily as cool as it has developed amongst young visual Boetto’s work in video and photography. announced one of the great shifts in human appraisal and analysis. Kathleen Boetto strikes artists working at the Akademie since the mid And thanks also to Linseed Projects for their consciousness not often -

Summaries of the Articles

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 09:53 Vie des arts Summaries of the Articles Numéro 44, automne 1966 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/58373ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) La Société La Vie des Arts ISSN 0042-5435 (imprimé) 1923-3183 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article (1966). Summaries of the Articles. Vie des arts, (44), 97–103. Tous droits réservés © La Société La Vie des Arts, 1966 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ SUMMARIES OF THE ARTICLES Translation by BILL TRENT tbe Canadian carrefour BY GILLES HÉNAULT Apart from artist-architect collaboration, it is of interest that once In the world of art, Canada is a carrefour, a sort of meeting place a building is completed, the owners automatically search out the of the great aesthetic currents of Europe and America, a part of the art vendors. An interesting example is the C.I.L. collection. But Paris-New York-San Francisco axis. Long the disciples of a pictur company officials also call on the artists when it comes time to esque provincialism, Canadian painters have for the past 20 years decorate their offices. -

Fine Canadian Art

HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE HEFFEL FINE ART FINE CANADIAN ART FINE CANADIAN ART FINE CANADIAN ART NOVEMBER 27, 2014 HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE VANCOUVER • CALGARY • TORONTO • OTTAWA • MONTREAL HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE ISBN 978~1~927031~14~8 SALE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 2014, TORONTO FINE CANADIAN ART AUCTION THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 2014 4 PM, CANADIAN POST~WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 7 PM, FINE CANADIAN ART PARK HYATT HOTEL, QUEEN’S PARK BALLROOM 4 AVENUE ROAD, TORONTO PREVIEW AT HEFFEL GALLERY, VANCOUVER 2247 GRANVILLE STREET SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 1 THROUGH TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4, 11 AM TO 6 PM PREVIEW AT GALERIE HEFFEL, MONTREAL 1840 RUE SHERBROOKE OUEST THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 13 THROUGH SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 11 AM TO 6 PM PREVIEW AT UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO ART CENTRE 15 KING’S COLLEGE CIRCLE ENTRANCE OFF HART HOUSE CIRCLE SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 22 THROUGH WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 10 AM TO 6 PM THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 10 AM TO 12 PM HEFFEL GALLERY, TORONTO 13 HAZELTON AVENUE, TORONTO ONTARIO, CANADA M5R 2E1 TELEPHONE 416 961~6505, FAX 416 961~4245 TOLL FREE 1 800 528-9608 WWW.HEFFEL.COM HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE VANCOUVER • CALGARY • TORONTO • OTTAWA • MONTREAL HEFFEL FINE ART AUCTION HOUSE CATALOGUE SUBSCRIPTIONS A Division of Heffel Gallery Inc. Heffel Fine Art Auction House and Heffel Gallery Inc. regularly publish a variety of materials beneficial to the art collector. An TORONTO Annual Subscription entitles you to receive our Auction Catalogues 13 Hazelton Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5R 2E1 and Auction Result Sheets. Our Annual Subscription Form can be Telephone 416 961~6505, Fax 416 961~4245 found on page 116 of this catalogue. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

Download Guide

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE FOR GRADES 5–12 LEARN ABOUT MODERN CANADIAN LANDSCAPES & THE GROUP OF SEVEN through the art of TOM THOMSON Click the right corner to MODERN CANADIAN LANDSCAPES & THE GROUP OF SEVEN TOM THOMSON through the art of return to table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 RESOURCE WHO WAS TIMELINE OF OVERVIEW TOM THOMSON? HISTORICAL EVENTS & ARTIST’S LIFE PAGE 4 PAGE 9 PAGE 12 LEARNING CULMINATING HOW TOM THOMSON ACTIVITIES TASK MADE ART: STYLE & TECHNIQUE PAGE 13 READ ONLINE DOWNLOAD ADDITIONAL TOM THOMSON: TOM THOMSON RESOURCES LIFE & WORK IMAGE FILE BY DAVID P. SILCOX EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE MODERN CANADIAN LANDSCAPES & THE GROUP OF SEVEN through the art of TOM THOMSON RESOURCE OVERVIEW This teacher resource guide has been designed to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Tom Thomson: Life & Work by David P. Silcox. The artworks within this guide and images required for the learning activities and culminating task can be found in the Tom Thomson Image File provided. Tom Thomson (1877–1917) is one of Canada’s most famous artists: his landscape paintings of northern Ontario have become iconic artworks, well-known throughout the country and a critical touchstone for Canadian artists. Thomson was passionate about the outdoors, and he was committed to experimenting with new ways to paint landscape. He had several friends who shared these interests, such as A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Lawren Harris (1885–1970), and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932); a few years after his premature death, these friends helped establish the Group of Seven, a collection of artists often credited with transforming Canadian art by creating modern depictions of national landscapes. -

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Annual Report 06/07 06/07 Annual Report of Finearts Museum the Montreal the MONTREAL MUSEUM of FINE ARTS

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Annual Report 06/07 Annual Report Annual Report 06/07 The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts THE MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS The 2006-2007 Annual Report Code of Ethics Annual Report of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is a production of the Advertising, Editorial Services At all times, the Trustees respect the Code and Graphic Design Department, Communications Division. of Ethics for Trustees of the Montreal Mu- seum of Fine Arts. No complaints have 06/07 Co-ordination: Emmanuelle Christen Texts: Stéphanie Kennan been filed with regard to the application of Translation and revision: Jo-Anne Hadley and Katrin Sermat this Code. Translation and revision of acquisitions: Each year, all of the Museum’s Trust- Marcia Couëlle and Donald Pistolesi Proofreading: Jane Jackel ees sign a declaration confirming that they Photography: Jean-François Brière, Christine Guest Conserving for All to Share and Brian Merrett are aware of the Code and agree to respect Graphic Design: it. In 2006-2007, all Trustees signed this The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, true to Guy Pilotte communication design inc. its vocation of acquiring and promoting the Printing: L’Empreinte declaration. work of Canadian and international artists past and present, has a mission to attract the broadest and most heterogeneous public possible, and to provide that public with first-hand access to a universal artistic heritage. Back cover: Pierre Soulages Painting, 222 x 157 cm, August 24, 1979 (detail) 1979 Anonymous gift © Pierre Soulages / SODRAC (2007) © The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2007 Legal deposit – 3rd quarter 2007 Bibliothèque nationale du Québec National Library of Canada ISBN 978-2-89192-316-3 THE MONTREAL MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS 1379-1380 Sherbrooke Street West Mailing address: P.O. -

Elements & Principles of Design

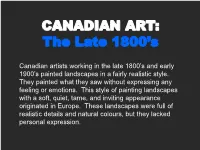

CANADIAN ART: The Late 1800’s Canadian artists working in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s painted landscapes in a fairly realistic style. They painted what they saw without expressing any feeling or emotions. This style of painting landscapes with a soft, quiet, tame, and inviting appearance originated in Europe. These landscapes were full of realistic details and natural colours, but they lacked personal expression. Homer Watson John A. Fraser September Afternoon, Eastern At the Rogers Pass, Summit of the Townships 1873 Selkirk Range, B.C. 1886 CANADIAN ART: THE GROUP OF SEVEN The Group of Seven was founded in 1920 to develop a new style of Canadian painting with a distinct Canadian identity. These artists painted what they saw, but added imagination and feeling. They were especially interested in expressing the wild, untamed spirit of the Canadian wilderness in their paintings. The artists often travelled into the wilderness to make sketches in the open air. They wanted to capture the atmosphere, the effects of light, and the spirituality and ruggedness of the northern Canadian landscape. In order to accomplish this, their style was also rugged, expressive, and powerful. THE GROUP OF SEVEN PAINTING STYLE a)Colours: bold and vibrant or bold and dark/dull high contrast between lights and darks b) Shapes/Forms: simplified with few details almost 2 dimensional abstract c) Brushstrokes: thick paint application (impasto) often visible (not blended) Franklin Carmichael Lake Wabagishik 1928 Mirror Lake 1929 Arthur Lismer A September Gale, Georgian Bay 1921 Bright Land 1938 J.E.H. MacDonald The Solemn Land 1921 Mist Fantasy 1922 F.H. -

Seeing and Not Seeing: Landscape Art As a Historical Source

ch08.qxd 2/5/08 1:41 PM Page 140 Seeing and Not Seeing: Landscape Art as a Historical Source COLIN M. COATES Colin Coates is the Canada Research Chair in Cultural Landscapes at Glendon College, York University. During the years that I taught Canadian Studies courses at the University of Edinburgh, I some- times asked my British students to complete the phrase, “As Canadian as ...”The answers they gave were usually fairly predictable: “maple syrup,” “snow,” “a Mountie.” If I had to answer the question myself, I would probably finish the sentence with “landscape.” After all, as the second- largest country in the world, Canada has a lot of landscape. More importantly, the image Canadians project to themselves and others is often of rural or “wilderness” landscapes, even if they rarely visit them, and the human population of the country is crowded into the cities and towns that hug the American border. But the images of Canada iconic to Canadians and tourists alike are usually (apparently) pristine forests, lakes, mountains, and icebergs, not the cities, high-rises, and highways that more accurately define the day-to-day life of the vast majority of Canadians today. Canadians are not unique in finding the essence of their country outside their urban settings. Many countries locate their self-image in the countryside or the wilderness: Scotland, for instance, markets its majestic lochs and craggy islands, even if most Scots live in the tamer cities and suburbs near the English border. In the Canadian case, landscapes are often refracted through particular aesthetic approaches. -

Acrylic Paint and Montreal Hard-Edge Painting Jessica Veevers a Thesis in the De

The Intersection of Materiality and Mattering: Acrylic Paint and Montreal Hard-Edge Painting Jessica Veevers A Thesis In the Department Of Art History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Art History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada January 2020 ©Jessica Veevers, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Jessica Veevers Entitled: The Intersection of Materiality and Mattering: Acrylic Paint and Montreal Hard-Edge Painting and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy (Art History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Haidee Wasson External Examiner Dr. Mark Cheetham External to Program Dr. Mark Sussman Examiner Dr. Steven Stowell Examiner Dr. Edith-Anne Pageot Thesis Supervisor Dr. Anne Whitelaw Approved by Dr. Kristina Huneault, Graduate Program Director January 10, 2020 Dr. Rebecca Taylor Duclos, Dean Faculty of Fine Arts iii ABSTRACT The Intersection of Materiality and Mattering: Acrylic Paint and Montreal’s Hard-Edge Painting Jessica Veevers, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2020 Set in Montreal with the advent of Hard-Edge painting and the invention of acrylic paint, this thesis takes a critical look at the relationship between materiality and mattering. The Hard-Edge painters, Guido Molinari, Claude Tousignant and Yves Gaucher undertook a new medium to express their new way of seeing and encountering the world and they did so in a way that was unique from other contemporaneous abstract painters.