(In)Formal Institutions.∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

The Glories of Norman Sicily Betty Main, SRC

The Glories of Norman Sicily Betty Main, SRC The Norman Palace in Palermo, Sicily. As Rosicrucians, we are taught to be they would start a crusade to “rescue” tolerant of others’ views and beliefs. We southern Italy from the Byzantine Empire have brothers and sisters of like mind and the Greek Orthodox Church, and throughout the world, of every race and restore it to the Church of Rome. As they religion. The history of humankind has were few in number, they decided to return often demonstrated the worst human to Normandy, recruit more followers, aspects, but from time to time, in what and return the following year. Thus the seemed like a sea of barbarism, there Normans started to arrive in the region, appeared periods of calm and civilisation. which was to become the hunting ground The era we call the Dark Ages in Europe, for Norman knights and others anxious was not quite as “dark” as may be imagined. for land and booty. At first they arrived as There were some parts of the Western individuals and in small groups, but soon world where the light shone like a beacon. they came flooding in as mercenaries, to This is the story of one of them. indulge in warfare and brigandage. Their Viking ways had clearly not been entirely It all started in the year 1016, when forgotten. a group of Norman pilgrims visited the shrine of St. Michael on the Monte Robert Guiscard and Gargano in southern Italy. After the Roger de Hauteville “pilgrims” had surveyed the fertile lands One of them, Robert Guiscard, of Apulia lying spread out before them, having established his ascendancy over the promising boundless opportunities for south of Italy, acquired from the papacy, making their fortunes, they decided that the title of Duke of Naples, Apulia, Page 1 Calabria, and Sicily. -

Sicily in Transition Research Project : Investigations at Castronovo Di Sicilia

This is a repository copy of Sicily in Transition Research Project : Investigations at Castronovo di Sicilia. Results and Prospects 2015. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/105192/ Version: Published Version Article: Carver, Martin Oswald Hugh orcid.org/0000-0002-7981-5741 and Molinari, Alessandra (2016) Sicily in Transition Research Project : Investigations at Castronovo di Sicilia. Results and Prospects 2015. Fasti On Line Documents & Research. pp. 1-12. ISSN 1828- 3179 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) licence. This licence allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon the work even for commercial purposes, as long as you credit the authors and license your new creations under the identical terms. All new works based on this article must carry the same licence, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Journal of Fasti Online (ISSN 1828-3179) ● Published by the Associazione Internazionale di Archeologia Classica ● Palazzo Altemps, Via Sant'Appolinare 8 – 00186 Roma ● Tel. / Fax: ++39.06.67.98.798 ● http://www.aiac.org; http://www.fastionline.org Sicily in Transition Research Project. Investigations at Castronovo di Sicilia. Results and Prospects, 2015 Martin Carver – Alessandra Molinari Il progetto Sicily in Transition è nato dalla collaborazione delle Università di York e di Roma Tor Vergata, con il pieno ap- poggio della Soprintendenza ai BB. -

Storia Militare Moderna a Cura Di VIRGILIO ILARI

NUOVA RIVISTA INTERDISCIPLINARE DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI STORIA MILITARE Fascicolo 7. Giugno 2021 Storia Militare Moderna a cura di VIRGILIO ILARI Società Italiana di Storia Militare Direttore scientifico Virgilio Ilari Vicedirettore scientifico Giovanni Brizzi Direttore responsabile Gregory Claude Alegi Redazione Viviana Castelli Consiglio Scientifico. Presidente: Massimo De Leonardis. Membri stranieri: Christopher Bassford, Floribert Baudet, Stathis Birthacas, Jeremy Martin Black, Loretana de Libero, Magdalena de Pazzis Pi Corrales, Gregory Hanlon, John Hattendorf, Yann Le Bohec, Aleksei Nikolaevič Lobin, Prof. Armando Marques Guedes, Prof. Dennis Showalter (†). Membri italiani: Livio Antonielli, Marco Bettalli, Antonello Folco Biagini, Aldino Bondesan, Franco Cardini, Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi, Piero del Negro, Giuseppe De Vergottini, Carlo Galli, Roberta Ivaldi, Nicola Labanca, Luigi Loreto, Gian Enrico Rusconi, Carla Sodini, Donato Tamblé, Comitato consultivo sulle scienze militari e gli studi di strategia, intelligence e geopolitica: Lucio Caracciolo, Flavio Carbone, Basilio Di Martino, Antulio Joseph Echevarria II, Carlo Jean, Gianfranco Linzi, Edward N. Luttwak, Matteo Paesano, Ferdinando Sanfelice di Monteforte. Consulenti di aree scientifiche interdisciplinari: Donato Tamblé (Archival Sciences), Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi (Architecture and Engineering), Immacolata Eramo (Philology of Military Treatises), Simonetta Conti (Historical Geo-Cartography), Lucio Caracciolo (Geopolitics), Jeremy Martin Black (Global Military History), Elisabetta Fiocchi Malaspina (History of International Law of War), Gianfranco Linzi (Intelligence), Elena Franchi (Memory Studies and Anthropology of Conflicts), Virgilio Ilari (Military Bibliography), Luigi Loreto (Military Historiography), Basilio Di Martino (Military Technology and Air Studies), John Brewster Hattendorf (Naval History and Maritime Studies), Elina Gugliuzzo (Public History), Vincenzo Lavenia (War and Religion), Angela Teja (War and Sport), Stefano Pisu (War Cinema), Giuseppe Della Torre (War Economics). -

Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica & the Balearic Islands

BETCHART EXPEDITIONS Inc. 17050 Montebello Road, Cupertino, CA 95014-5435 SICILY, SARDINIA, CORSICA & THE BALEARIC ISLANDS Stepping Stones of Cultures Private-Style Cruising Aboard the All-Suite, 100-Guest Corinthian May 6 – 14, 2013 BOOK BY FEBRUARY 8, 2013 TO RECEIVE 1 FREE PRE-CRUISE HOTEL NIGHT IN PALERMO Dear Traveler, For thousands of years, wave after wave of civilizations have passed over the islands of the Mediterranean, leaving their mark on art and architecture, on language, culture, and cuisine. For this exceptional voyage we have selected four destinations that are especially fascinating examples of the complex history of the Mediterranean: Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands. This May, we would like you to join us on a private-style cruise to these delightful islands. The Carthaginians and the Greeks, the Romans and the Byzantines, the Arabs and the Normans all influenced the history and culture of Sicily. We’ll visit the magnificent Doric temple at Segesta, built by Greek colonists in 420 B.C., and explore the ancient town of Erice, dominated by a 12th-century Norman castle standing on the remains of a temple that tradition says was built by the Trojans. Sardinia is an especially remarkable island, with more than 7,000 prehistoric sites dating back nearly 4,000 years. We’ll explore the finest of these Nuraghic sites, as well as Alghero, an enchanting port town that for centuries was ruled by the kings of Aragon. To this day, many residents of Alghero speak the island’s Catalan dialect. The Balearic Islands are an archipelago off the northeast coast of Spain. -

ROGER II of SICILY a Ruler Between East and West

. ROGER II OF SICILY A ruler between east and west . HUBERT HOUBEN Translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org Originally published in German as Roger II. von Sizilien by Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 and C Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt, 1997 First published in English by Cambridge University Press 2002 as Roger II of Sicily English translation C Cambridge University Press 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Bembo 10/11.5 pt. System LATEX 2ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Houben, Hubert. [Roger II. von Sizilien. English] Roger II of Sicily: a ruler between east and west / Hubert Houben; translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn. p. cm. Translation of: Roger II. von Sizilien. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65208 1 (hardback) isbn 0 521 65573 0 (paperback) 1. Roger II, King of Sicily, d. -

Capetian France (987–1328)

FORUM Capetian France (987–1328) Introduction Damien Kempf If “France is a creation of its medieval history,”1 the rule of the Cape- tian dynasty (987–1328) in particular is traditionally regarded as the beginning of France as a nation.2 Following the narrative established by Joseph Strayer’s influential bookOn the Medieval Origins of the Mod- ern State, historians situate the construction of the French nation- state in the thirteenth century, under the reigns of Philip Augustus (1180– 1223) and Louis IX (1226–70). Territorial expansion, the development of bureaucracy, and the centralization of the royal government all con- tributed to the formation of the state in France.3 Thus it is only at the end of a long process of territorial expansion and royal affirmation that the Capetian kings managed to turn what was initially a disparate and fragmented territory into a unified kingdom, which prefigured the modern state. In this teleological framework, there is little room or interest for the first Capetian kings. The eleventh and twelfth centuries are still described as the “âge des souverains,” a period of relative anarchy and disorder during which the aristocracy dominated the political land- scape and lordship was the “normative expression of human power.”4 Compared to these powerful lords, the early Capetians pale into insignifi- cance. They controlled a royal domain centered on Paris and Orléans and struggled to keep at bay the lords dominating the powerful sur- rounding counties and duchies. The famous anecdote reported by the Damien Kempf is senior lecturer in medieval history at the University of Liverpool. -

2 Social Aspects of the Ravenna Papyri: the Social Structure of the P

FRAGMENTS FROM THE PAST A social-economic survey of the landholding system in the Ravenna Papyri NIELS PAUL ARENDS Fragments from the past A social-economic survey of the landholding system in the Ravenna Papyri Niels Paul Arends Universiteit Leiden 2018 Acknowledgements I would like to thank dr. Rens Tacoma who, at one point, invited me to write a thesis about the Ravenna Papyri, a topic that has, for at least the last one and a half year, gotten my full attention. I want to thank him and Prof. Dr. Dominic Rathbone for all the commentaries given on this work, their helpful comments, and for their tips and tricks. It is to my understanding that they have enlightened me with their vast ‘know-how’ of this specific topic, and that I, certainly, could not have done it without their help. Further, I want to thank my parents, Els Loef and Paul Arends, who have given me helpful comments as well, although it is has been their ongoing support for my study that helped me even more. Lastly, I want to thank Marielle de Haan, who has been a great proofreader, and has given me the attention when I needed it most. N., 27-6-2018 Cover picture: P. Ital. 10-11 A, taken from J. O. Tjäder (1954) 56. Contents Introduction p. 1 1 Economic aspects of the Ravenna Papyri: Fundi, massae, size and wealth p.6 1.1 Fundi, massae, names and locations: Regional trends and beyond p.9 1.2 Economic theories, and guessing the variables: Scale and Wealth p. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE Noble castles of the late Middle Ages in Northwest Italy, International Conference on Modern Age Fortifications of the Mediterranean Coast. Original Noble castles of the late Middle Ages in Northwest Italy, International Conference on Modern Age Fortifications of the Mediterranean Coast / BELTRAMO, SILVIA. - STAMPA. - vol. VII(2018), pp. 7-13. Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2747719 since: 2019-08-18T00:32:19Z Publisher: Politecnico di Torino Published DOI: Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 DEFENSIVE ARCHITECTURE OF THE MEDITERRANEAN 7 Anna MAROTTA, Roberta SPALLONE (Eds.) DEFENSIVE ARCHITECTURE OF THE MEDITERRANEAN Vol. VII PROCEEDINGS of the International Conference on Modern Age Fortification of the Mediterranean Coast FORTMED 2018 DEFENSIVE ARCHITECTURE OF THE MEDITERRANEAN Vol. VII Editors Anna Marotta, Roberta Spallone Politecnico di Torino. Italy POLITECNICO DI TORINO Series Defensive Architectures of the Mediterranean General editor Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro The papers published in this volume have been peer-reviewed by the Scientific Committee of FORTMED2018_Torino © editors Anna Marotta, Roberta Spallone © papers: the authors © 2018 edition: Politecnico di Torino ISBN: 978-88-85745-10-0 FORTMED - Modern Age Fortification of the Mediterranean Coast, Torino, 18th, 19th, 20th October 2018 Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean. / Vol VII / Marotta, Spallone (eds.) © 2018 Politecnico di Torino Organization and Committees Organizing Committee Anna Marotta. (Chair). Politecnico di Torino. Italy Roberta Spallone. (Chair). Politecnico di Torino. Italy Marco Vitali. (Program Co-Chair and Secretary). -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non- commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Katarzyna Kosior (2017) "Becoming and Queen in Early Modern Europe: East and West", University of Southampton, Faculty of the Humanities, History Department, PhD Thesis, 257 pages. University of Southampton FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Becoming a Queen in Early Modern Europe East and West KATARZYNA KOSIOR Doctor of Philosophy in History 2017 ~ 2 ~ UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES History Doctor of Philosophy BECOMING A QUEEN IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE: EAST AND WEST Katarzyna Kosior My thesis approaches sixteenth-century European queenship through an analysis of the ceremonies and rituals accompanying the marriages of Polish and French queens consort: betrothal, wedding, coronation and childbirth. The thesis explores the importance of these events for queens as both a personal and public experience, and questions the existence of distinctly Western and Eastern styles of queenship. A comparative study of ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ ceremony in the sixteenth century has never been attempted before and sixteenth- century Polish queens usually do not appear in any collective works about queenship, even those which claim to have a pan-European focus. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

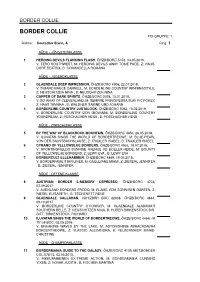

Border Collie

BORDER COLLIE BORDER COLLIE FCI-GRUPPE: 1 Richter: Deutscher Erwin, A Ring: 1 RÜDE - JÜNGSTENKLASSE 1 HERDING DEVILS FLANKING FLASH, ÖHZB/BORC 5152, 03.05.2019, V: TERO SOUTHWEST, M: HERDING DEVILS AWAY TOME PACE, Z: HAUS- DORF BEATRIX, B: COMANDELLA ROMANA RÜDE - JUGENDKLASSE 2 GLAENDALE DEEP IMPRESSION, ÖHZB/BORC 4906, 22.07.2018, V: SIMARO BRUCE DARNELL, M: BORDERLINE COUNTRY WINNINGSTYLE, Z: NEUSCHITZER NINA , B: NEUSCHITZER NINA 3 CAPPER OF DARK SPIRITS, ÖHZB/BORC 5078, 15.01.2019, V: SO WHAT OF CLEVERLAND, M: SEMPRE PRINCIPESSA SUKI PIC POKEY, Z: HAAS TAMARA , B: WALDHER SABINE UND JOHANN 4 BORDERLINE COUNTRY JUSTALOOK, ÖHZB/BORC 5062, 10.02.2019, V: BORDERLINE COUNTRY DON GIOVANNI, M: BORDERLINE COUNTRY YOURDREAM, Z: POSCHACHER HEIDI , B: POSCHACHER HEIDI RÜDE - ZWISCHENKLASSE 5 BY THE WAY OF BLACKROCK MOUNTAIN, ÖHZB/BORC 4850, 28.05.2018, V: ILUVATAR SINGS THE WORLD OF BORDERTREOWE, M: BLUE-PEARL VON DER SAUSSBACHKLAUSE, Z: TRAXLER ISABEL, B: TRAXLER ISABEL 6 CYRANO OF YELLOWBLUE BORDERS, ÖHZB/BORC 4933, 18.07.2018, V: SPORTINGFIELDS SUNRISE AVENUE VD BOELER-HEIDE, M: BOUNTY OF YELLOWBLUE BORDERS, Z: LEWY EVA , B: LEWY EVA 7 BORDERCULT ELLEHAMMER, ÖHZB/BORC 4869, 19.05.2018, V: BORDERFAME STAR LINES, M: QUELLYANE MIAMI, Z: ZIESERL JENNIFER , B: ZIESERL JENNIFER RÜDE - OFFENE KLASSE 8 AUSTRIAN BORDER E-MEMORY ESPRESSO, ÖHZB/BORC 4703, 07.09.2017, V: AUENLAND BORDERS FRODO, M: FLAME VOM SONNIGEN GARTEN, Z: RIESEL ELISABETH , B: TSCHENETT RENE 9 GLAENDALE CALLAHAN, VDH/ZBRH BOC 22808, ÖHZB/BORC 4681, 09.10.2017, V: BORDERLINE COUNTRY