Southern Africa's Wildlife Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Miniaturization of a New Amniote Vertebrate and Insights Into the Evolution of Genital Size in Chameleons

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Extreme miniaturization of a new amniote vertebrate and insights into the evolution of genital size in chameleons Frank Glaw1*, Jörn Köhler2, Oliver Hawlitschek3, Fanomezana M. Ratsoavina4, Andolalao Rakotoarison4, Mark D. Scherz5 & Miguel Vences6 Evolutionary reduction of adult body size (miniaturization) has profound consequences for organismal biology and is an important subject of evolutionary research. Based on two individuals we describe a new, extremely miniaturized chameleon, which may be the world’s smallest reptile species. The male holotype of Brookesia nana sp. nov. has a snout–vent length of 13.5 mm (total length 21.6 mm) and has large, apparently fully developed hemipenes, making it apparently the smallest mature male amniote ever recorded. The female paratype measures 19.2 mm snout–vent length (total length 28.9 mm) and a micro-CT scan revealed developing eggs in the body cavity, likewise indicating sexual maturity. The new chameleon is only known from a degraded montane rainforest in northern Madagascar and might be threatened by extinction. Molecular phylogenetic analyses place it as sister to B. karchei, the largest species in the clade of miniaturized Brookesia species, for which we resurrect Evoluticauda Angel, 1942 as subgenus name. The genetic divergence of B. nana sp. nov. is rather strong (9.9‒14.9% to all other Evoluticauda species in the 16S rRNA gene). A comparative study of genital length in Malagasy chameleons revealed a tendency for the smallest chameleons to have the relatively largest hemipenes, which might be a consequence of a reversed sexual size dimorphism with males substantially smaller than females in the smallest species. -

Ozzie Da Ros Pond Completed

NEWSLETTER • WINTER 2019 A LOTUSLAND LEGEND Ozzie Da Ros JAPANESE GARDEN RENOVATION Pond Completed LETTER FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Dear Members and Friends, IN THIS FIRST ISSUE OF YOUR 2019 newsletter we share stories of the past and plans for the future. 695 Ashley Road We dedicate the lead article to Ozzie Da Ros, whose recent Santa Barbara, California 93108 passing signaled the end of an era. Ozzie was the last of 805.969.3767 • www.lotusland.org many talented craftsmen and expert plantsmen who worked 2019 BOARD OF TRUSTEES directly with Ganna Walska over several decades to make Daniel Bifano, President her dream of a “most outstanding center of horticultural Geoff Crane significance and educational use” become a reality, a top Lesley Cunningham Dorothy H. Gardner ten garden of the world. Fortunately, we were able to gather Anthony Grumbine written or oral memoirs from most of Walska’s collaborators Belle Hahn so their accounts may guide us as we tend the Garden now David M. Jones and in perpetuity. Joseph Marek Suzanne Mathews Nowhere is this commitment better exemplified than in the renovation of the Japanese Mimi Michaelis Garden. Over six years we conducted intensive research, peeling away the multiple historic Alexandra Morse Connie Pearcy layers of the garden to understand and preserve the significant aspects of each. We honor Eileen Rasmussen the garden and its makers even as we conscientiously add a new layer that addresses Stephen P. Schaible the modern obligations of an historic estate turned public garden. With the garden’s George Schoellkopf completion this year, all guests will have safe, comfortable access to the garden and new, Mick Thomas Caroline R. -

Genetic Diversity of Aloe Species in Kenya and the Efficacy of Aloe Secundiflora, Aloe Lateritia and Aloe Turkanesis on Fusarium

(icnetic diversity of Aloe species in Kenya and the efficacy of Aloe secundiflora, Aloe lateritia and Aloe turkanesis on Fusarium oxysporum and Pythium ultimum 1 A research thesis submitted for examination in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the award of Master of Science in Microbiology 156/68748/2011 SCHOOL OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES COLLEGE OF BIOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI December, 2015 University of N AIROBI Library DECLARATION I his thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in anj other University or any other institution of higher learning. Micheni C. Mugambi Da.e...2j..i .'.l2 ..:,.2 -O lS .......... I his thesis has been submitted with our approval as Supervisors. Dr. Maina Wagacha School of Biological Sciences Universiii_tt£-Nairobi Date .J.V l.& l. Dr. Nelson Amugune School of Biological Sciences University of Nairobi Sign..!!p^.^ff.. ........ Dr. Simon T. Gichuki Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) Sign.....C ^dLJ ..... Date....c£-£)t5 ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my loving mum Elyjoy Muthoni Michcni and dad Isaac Micheni Nkari who have gone out of their way to support my education. I also dedicate this work to my brothers Maurice Murimi and Brian Muchiri Micheni who have been a constant source of encouragement. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am heavily indebted to my supervisors Dr. Maina Wagacha, Dr. Nelson Amugune and Dr.Simon Gichuki for their invaluable support, training, mentorship, and advice throughout this work. Without your support, this work would not have achieved anything significant. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Blumgart Et Al 2017- Herpetological Survey Nosy Komba

Journal of Natural History ISSN: 0022-2933 (Print) 1464-5262 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah20 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy To cite this article: Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy (2017): Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar, Journal of Natural History, DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Published online: 28 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnah20 Download by: [BBSRC] Date: 21 March 2017, At: 02:56 JOURNAL OF NATURAL HISTORY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart a, Julia Dolhema and Christopher J. Raxworthyb aMadagascar Research and Conservation Institute, BP 270, Hellville, Nosy Be, Madagascar; bDivision of Vertebrate Zoology, American, Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY A six month herpetological survey was undertaken between March Received 16 August 2016 and September 2015 on Nosy Komba, an island off of the north- Accepted 17 January 2017 west coast of mainland Madagascar which has undergone con- KEYWORDS fi siderable anthropogenic modi cation. A total of 14 species were Herpetofauna; conservation; found that have not been previously recorded on Nosy Komba, Madagascar; Nosy Komba; bringing the total island diversity to 52 (41 reptiles and 11 frogs). -

Foliicolous Microfungi Occurring on <I>Encephalartos</I>

Persoonia 21, 2008: 135–146 www.persoonia.org RESEARCH ARTICLE doi:10.3767/003158508X380612 Foliicolous microfungi occurring on Encephalartos P.W. Crous1,2, A.R. Wood3, G. Okada4, J.Z. Groenewald1 Key words Abstract Species of Encephalartos, commonly known as bread trees, bread palms or cycads are native to Africa; the genus encompasses more than 60 species and represents an important component of the indigenous African Catenulostroma flora. Recently, a leaf blight disease was noted on several E. altensteinii plants growing at the foot of Table Mountain Cladophialophora in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens of South Africa. Preliminary isolations from dead and dying leaves of E. alten Dactylaria steinii, E. lebomboensis and E. princeps, collected from South Africa, revealed the presence of several novel ITS nrDNA microfungi on this host. Novelties include Phaeomoniella capensis, Saccharata kirstenboschensis, Teratosphaeria LSU nrDNA altensteinii and T. encephalarti. New host records of species previously only known to occur on Proteaceae include Ochroconis Cladophialophora proteae and Catenulostroma microsporum, as well as a hyperparasite, Dactylaria leptosphaerii Phaeomoniella cola, occurring on ascomata of T. encephalarti. Saccharata systematics Article info Received: 1 October 2008; Accepted: 14 October 2008; Published: 22 October 2008. Teratosphaeria INTRODUCTION observed on several Encephalartos palms growing in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens of South Africa, as well as Encephalartos (Zamiaceae) is a genus of cycads indigenous in the KwaZulu-Natal Province. The aim of the present study to Africa. Due to its edible pith, species of Encephalartos are was therefore to determine if any microfungi could be isolated commonly referred to as bread trees or bread palms (www. -

Download the PDF File

ISSN 2473-442X CONTENTS Message from Dr. Patrick Griffith, Co-chair, IUCN/SSC CSG 3 Official newsletter of IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group Botanic Garden: In Focus Vol. IV I Issue 2 I December 2019 Montgomery Botanical Center’s Cycad Collection – Focus on research and conservation 5 Michael Calonje & Patrick Griffith Feature Articles Towards an approach for the conservation and illegal trade prevention of South Africa’s endangered Encephalartos spp. 10 James A. R. Clugston, Michelle Van Der Bankand Ronny M. Kobongo Fire is the most important threat for conservation of Dioon merolae (espadaña) in the hill Nambiyigua, municipality of Villaflores, Chiapas, Mexico 13 Miguel Angel Pérez-Farrera & Mauricio Martínez Martínez Ex-situ Cycad Conservation [1]: Public and Private Collections 16 Chip Jones & JS Khuraijam The Cycad Specialist Group (CSG) is a component of the IUCN Species Research and Conservation News Survival Commission (IUCN/SSC). It consists of a group of volunteer The Cycad Extinction Crisis in South Africa 19 experts addressing conservation Wynand van Eeden & Tim Gregory issues related to cycads, a highly What is Ceratozamia becerrae ? 21 threatened group of land plants. The Andrew P. Vovides, Miguel Angel Pérez-Farrera & José Said Gutiérrez-Ortega CSG exists to bring together the world’s cycad conservation expertise, Preliminary Finding: Seed longevity of Encephalartos in controlled storage 23 and to disseminate this expertise to Ngawethu Ngaka and Phakamani Xaba organizations and agencies which can use this guidance to advance cycad Meeting Reports conservation. 2nd Nong Nooch Cycad Horticulture Workshop 25 Official website of CSG: Anders Lindstrom http://www.cycadgroup.org/ Plant Conservation Genetics Workshop 26 Co-Chairs Caroline Iacuaniello, Stephanie Steele & Christy Powell John Donaldson Patrick Griffith CSG Members 28 Vice Chairs Michael Calonje Cristina Lopez-Gallego Red List Authority Coordinator De Wet Bosenberg CSG Newsletter Committee JS Khuraijam, Editor Irene Terry Andrew P. -

Coevolution of Cycads and Dinosaurs George E

Coevolution of cycads and dinosaurs George E. Mustoe* INTRODUCTION TOXICOLOGY OF EXTANT CYCADS cycads suggests that the biosynthesis of ycads were a major component of Illustrations in textbooks commonly these compounds was a trait that C forests during the Mesozoic Era, the depict herbivorous dinosaurs browsing evolved early in the history of the shade of their fronds falling upon the on cycad fronds, but biochemical evi- Cycadales. Brenner et al. (2002) sug- scaly backs of multitudes of dinosaurs dence from extant cycads suggests that gested that macrozamin possibly serves a that roamed the land. Paleontologists these reconstructions are incorrect. regulatory function during cycad have long postulated that cycad foliage Foliage of modern cycads is highly toxic growth, but a strong case can be made provided an important food source for to vertebrates because of the presence that the most important reason for the reptilian herbivores, but the extinction of two powerful neurotoxins and carcin- evolution of cycad toxins was their of dinosaurs and the contemporaneous ogens, cycasin (methylazoxymethanol- usefulness as a defense against foliage precipitous decline in cycad popula- beta-D-glucoside) and macrozamin (beta- predation at a time when dinosaurs were tions at the close of the Cretaceous N-methylamine-L-alanine). Acute symp- the dominant herbivores. The protective have generally been assumed to have toms triggered by cycad foliage inges- role of these toxins is evidenced by the resulted from different causes. Ecologic tion include vomiting, diarrhea, and seed dispersal characteristics of effects triggered by a cosmic impact are abdominal cramps, followed later by loss modern cycads. a widely-accepted explanation for dino- of coordination and paralysis of the saur extinction; cycads are presumed to limbs. -

English Cop17 Inf. 47 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

Original language: English CoP17 Inf. 47 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 TRADE STUDY OF SELECTED EAST AFRICAN TIMBER PRODUCTION SPECIES This document has been submitted by Germany* in relation to agenda items 62, 77 and 88. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP17 Inf. 47 – p. 1 Anthony B. Cunningham Trade study of selected east African timber production species BfN-Skripten 445 2016 Trade study of selected east African timber production species Handelsstudie zu ostafrikanischen Holzarten (FKZ 3514 53 2003) Anthony B. Cunnigham Cover picture: A worker of a sawmill in front of Dalbergia melanoxylon logs in Montepuez/Mozambique (A.B. Cunningham) Author’s address: Dr. Anthony B. Cunningham Cunningham Consultancy WA Pty Ltd. 2 Tapper Street Au-6162 Fremantle E-Mail: [email protected] Scientific Supervision at BfN: Dr. Daniel Wolf Division II 1.2 “Plant Conservation“ This publication is included in the literature database “DNL-online” (www.dnl-online.de) BfN-Skripten are not available in book trade. Publisher: Bundesamt für Naturschutz (BfN) Federal Agency for Nature Conservation Konstantinstrasse 110 53179 Bonn, Germany URL: http://www.bfn.de The publisher takes no guarantee for correctness, details and completeness of statements and views in this report as well as no guarantee for respecting private rights of third parties. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

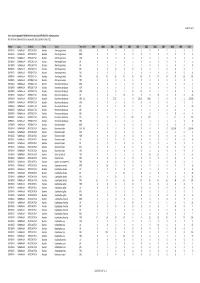

Gross Trade in Appendix II FAUNA (Direct Trade Only), 1999-2010 (For

AC25 Inf. 5 (1) Gross trade in Appendix II FAUNA (direct trade only), 1999‐2010 (for selection process) N.B. Data from 2009 and 2010 are incomplete. Data extracted 1 April 2011 Phylum Class TaxOrder Family Taxon Term Unit 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BOD 0 00001000102 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BON 0 00080000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia HOR 0 00000110406 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia LIV 0 00060000006 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKI 1 11311000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKP 0 00000010001 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKU 2 052101000011 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia TRO 15 42 49 43 46 46 27 27 14 37 26 372 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Antilope cervicapra TRO 0 00000020002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae BOD 0 00100001002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOP 0 00200000002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOR 0 0010100120216 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae LIV 0 0 5 14 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 49 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA KIL 0 5 27.22 0 0 272.16 1000 00001304.38 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA 0 00000000101 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae -

Cop16 Inf. 34 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement En Anglais)

CoP16 Inf. 34 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Sixteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok (Thailand), 3-14 March 2013 CITES TRADE – A GLOBAL ANALYSIS OF TRADE IN APPENDIX-I LISTED SPECIES 1. The attached document has been submitted by the Secretariat at the request of the UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC)* in relation to item 21 on Capacity building. 2. The research was facilitated through funds made available by the Government of Germany. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP16 Inf. 34 – p. 1 CITES Trade - A global analysis of trade in Appendix I-listed species United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre February, 2013 UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road Cambridge CB3 0DL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unep-wcmc.org The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment centre of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. The Centre has been in operation for over 30 years, combining scientific research with practical policy advice.