INVESTIGATING at the WASHINGTON POST Steven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2843/illinois-municipalities-v-purdue-pharma-et-al-complaint-rff-932843.webp)

Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]

FILED 12-Person Jury 7/19/2018 7:00 AM DOROTHY BROWN CIRCUIT CLERK COOK COUNTY, IL 2018CH09020 IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CHANCERY DIVISION CITY OF HARVEY, VILLAGE OF BROADVIEW, Case No. 2018CH09020 VILLAGE OF CHICAGO RIDGE, VILLAGE OF DOLTON, VILLAGE OF HOFFMAN ESTATES, VILLAGE OF MAYWOOD, VILLAGE OF MERRIONETTE PARK, VILLAGE OF NORTH RIVERSIDE, VILLAGE OF ORLAND PARK, CITY OF PEORIA, VILLAGE OF POSEN, VILLAGE OF RIVER GROVE, VILLAGE OF STONE PARK, and ORLAND FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT, Plaintiffs, FILED DATE: 7/19/2018 7:00 AM 2018CH09020 v. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA, INC., PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., RHODES PHARMACEUTICALS, CEPHALON, INC., TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC, JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMACUETICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMAEUTICA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., NORMACO, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS, INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., ALLERGAN PLC, ACTAVIS PLC, WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, MALLINCKRODT PLC, MALLINCKRODT LLC, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., MCKESSON CORPORATION, PAUL MADISON, WILLIAM MCMAHON, and JOSEPH GIACCHINO, Defendants. COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs City of Harvey, Village of Broadview, Village of Chicago Ridge, Village of Dolton, Village of Hoffman Estates, Village of Maywood, Village of Merrionette Park, Village 1 of North Riverside, Village of Orland Park, City of Peoria, Village of Posen, Village of River Grove, Village of Stone Park, and Orland Fire Protection District bring this Complaint and Demand for Jury Trial to obtain redress in the form of monetary and injunctive relief from Defendants for their role in the opioid epidemic that has caused widespread harm and injuries to Plaintiffs’ communities. -

1:17-Md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. Pageid #: 13544

Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. PageID #: 13544 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION IN RE NATIONAL PRESCRIPTION MDL No. 2804 OPIATE LITIGATION Case No. 17-md-2804 This document relates to: Judge Dan Aaron Polster Case No. 18-OP-45332 (N.D. Ohio) BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA, SECOND AMENDED COMPLAINT (REDACTED) Plaintiff, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL vs. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA INC., THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICA, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., NORAMCO, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL- JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., CEPHALON, INC., ALLERGAN PLC f/k/a ACTAVIS PLC, ALLERGAN FINANCE LLC, f/k/a ACTAVIS, INC., f/k/a WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC. f/k/a WATSON PHARMA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., MALLINCKRODT PLC, 1545690.37 Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 2 of 315. PageID #: 13545 MALLINCKRODT LLC, SPECGX LLC, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., McKESSON CORPORATION, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, HEALTH MART SYSTEMS, INC., H. D. SMITH, LLC d/b/a HD SMITH, f/k/a H.D. SMITH WHOLESALE DRUG CO., H. D. SMITH HOLDINGS, LLC, H. D. SMITH HOLDING COMPANY, CVS HEALTH CORPORATION, WALGREENS BOOTS ALLIANCE, INC. a/k/a WALGREEN CO., and WAL-MART INC. f/k/a WAL-MART STORES, INC., Defendants. -

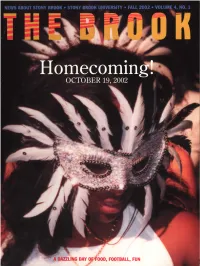

Thebrook Fall02.Pdf

DAY O'OOD, FOOTBALL, FUN nte I)sk of Jane Knap CONTEINTS To all my fellow Stony Brook alumni, I'm delighted to What's New On Campus 3 greet you as incoming president of the Stony Brook Ambulatory Surgery Center Opens; Asian Fall Festival at Stony Brook Alumni Association. Thanks to outgoing president Mark Snyder, I'm taking the reins of a dynamic organization Research Roundup 4 Geometry as a spy tool? Modern art on the with a real sense of purpose and ambition. Web-a new interactive medium. How a This is an exciting time to be a Stony Brook alum. Evidence turkey is helping Stony Brook researchers combat osteoporosis of a surging University is all around us. From front-page New York Times coverage of Professor Eckard Wimmer's synthesis of Extra! Extra! 6 the polio virus to Shirley Strum Kenny's ongoing transformation Former Stony Brook Press editor wins journalism's most coveted prize-the Pulitzer of the campus, Stony Brook is happening. Even the new and expanded Brook you're reading demonstrates that Stony Brook Catch Our Rising Stars 8 Meet is a class act. Stony Brook's student ambassadors- as they ascend the academic heights For alumni who haven't been back to campus in years, it's difficult to capture in words the spirit of Stony Brook today. Past and Present 10 A conversation with former University Even for those of us who come from an era when Stony Brook President John S. Toll and President Kenny was more grime than grass, today our alma mater is a source of tremendous pride--one of the nation's elite universities. -

Law As Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Law as Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism Roy Shapir Legal scholarshave long recognized that the media plays a key role in assuring the proper functioning of political and business markets Yet we have understudied the role of law in assuring effective media scrutiny. This Article develops a theory of law as source. The basicpremise is that the law not only regulates what the media can or cannot say, but also facilitates media scrutiny by producing information. Specifically, law enforcement actions, such as litigationor regulatory investigations, extract information on the behaviorofpowerfulplayers in business or government. Journalists can then translate the information into biting investigative reports and diffuse them widely, thereby shapingplayers' reputationsand norms. Levels of accountabilityin society are therefore not simply a function of the effectiveness of the courts as a watchdog or the media as a watchdog but rather a function of the interactions between the two watchdogs. This Article approaches, from multiple angles, the questions of how and how much the media relies on legal sources. I analyze the content of projects that won investigative reportingprizes in the past two decades; interview forty veteran reporters; scour a reporters-onlydatabase of tip sheets and how-to manuals; go over * IDC Law School. I thank participants in the Information in Litigation Roundtable at Washington & Lee, the Annual Corporate and Securities Litigation Workshop at UCLA, several conferences at IDC, the American Law and Economics Association annual conference at Boston University, and the Crisis in the Theory of the Firm conference and the Annual Reputation Symposium at Oxford University, as well as Jonathan Glater, James Hamilton, Andrew Tuch, and Verity Winship for helpful comments and discussions. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournalmayjun2004; Thu Apr 1

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 20 - 29 TRACKING SEX OFFENDERS TABLE OF CONTENTS MAY/JUNE 2004 OFFENDER SCREENING Likely predators released 4 Media insurers may push despite red-flag testing strong journalism training By John Stefany to manage risks, costs (Minnneapolis) Star Tribune By Brant Houston The IRE Journal STATE REGISTRY System fails to keep tabs 10 Top investigative work on released sex offenders named in 2003 IRE Awards By Frank Gluck By The IRE Journal The (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) Gazette 14 2004 IRE Conference to feature best in business COACHING THREAT By The IRE Journal Abuse of female athletes often covered up, ignored 16 BUDGET PROPOSAL By Christine Willmsen Organization maintains steady, conservative The Seattle Times course in light of tight training, data budgets in newsrooms By Brant Houston The IRE Journal 30 IMMIGRANT PROFILING 18 PUBLIC RECORDS Arabs face scrutiny in Detroit area Florida fails access test in joint newspaper audit in two years following 9/11 terrorist attacks By John Bebow By Chris Davis and Matthew Doig for The IRE Journal Sarasota Herald-Tribune 19 FOI REPORT 32 Irreverent approach to freelancing Privacy exemptions explains the need to break the rules may prove higher hurdle By Steve Weinberg than national security The IRE Journal By Jennifer LaFleur Checking criminal backgrounds The Dallas Morning News 33 By Carolyn Edds The IRE Journal ABOUT THE COVER 34 UNAUDITED STATE SPENDING Law enforcement has a tough Yes, writing about state budgets can sometimes be fun time keeping track of sexual By John M.R. Bull predators – often until they The (Allentown, Pa.) Morning Call re-offend and find themselves 35 LEGAL CORNER back in custody. -

Justice Heartland

13TH ANNUAL HARRY FRANK GUGGENHEIM SYMPOSIUM ON CRIME IN AMERICA JUSTICE IN THE HEARTLAND FEBRUARY 15TH AND 16TH, 2018 JOHN JAY COLLEGE 524 W. 59TH STREET NEW YORK, NY AGENDA THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 15 All Thursday panels take place in the Moot Court, John Jay College, 6th Floor of the new building 8:30 – 9:00am CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 12:30 – 2:30pm LUNCH for Fellows and invited guests only 9:00 – 9:30am WELCOME THE WHITE HOUSE PRISON Stephen Handelman, Director, Center on Media REFORM INITIATIVES Crime and Justice, John Jay College Mark Holden, Senior VP and General Counsel, Daniel F. Wilhelm, President, Harry Frank Koch Industries Guggenheim Foundation 2:30 – 4:00pm Karol V. Mason, President, John Jay College PANEL 3: of Criminal Justice CRIME TRENDS 2017-2018— 9:30 – 11:00am IS THE HOMICIDE ‘SPIKE’ REAL? PANEL 1: OPIATES— Thomas P. Abt, Senior Fellow, Harvard Law School AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY (PART 1) Alfred Blumstein, J. Erik Jonsson University Professor of Urban Systems and Operations Research, José Diaz-Briseño, Washington correspondent, Carnegie Mellon University La Reforma, Mexico Shytierra Gaston, Assistant Professor, Department Paul Cell, First Vice President, International of Criminal Justice, Indiana University-Bloomington Association of Chiefs of Police; Chief of Police, Montclair State University (NJ) Richard Rosenfeld, Founders Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University Rita Noonan, Chief, Health Systems and Trauma of Missouri - St. Louis Systems Branch, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MODERATOR Cheri Walter, Chief Executive Officer, The Ohio Robert Jordan Jr, former anchor, Chicago WGN-TV Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities MODERATOR 4:00 – 4:15pm BREAK Kevin Johnson, journalist, USA Today 4:15 – 6:00pm 11:00am – 12:30pm PANEL 4: CORRECTIONS / PANEL 2: OPIATES— SENTENCING REFORM UPDATE THE BATTLE SO FAR (PART 2) Leann Bertsch, President, Association of State Correctional Administrators; Director, North Dakota The Hon. -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Media Coordinators: Michael Cavaiola Wendy A. Oscarson Amy H. Gross James D. Saris HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Molly Cain Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Bill Walsh, Times-Picayne, Chair Thomas Ferraro, Reuters, Secretary Susan Ferrechio, Congressional Quarterly Carl Hulse, New York Times Andrew Taylor, Associated Press RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press

PRESS GALLERIES * SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Senior Media Coordinators: Amy H. Gross Kristyn K. Socknat Media Coordinators: James D. Saris Wendy A. Oscarson-Kirchner Elizabeth B. Crowley HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Anderson Laura Reed Drew Cannon Molly Cain STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Thomas Burr, The Salt Lake Tribune, Chair Joseph Morton, Omaha World-Herald, Secretary Jim Rowley, Bloomberg News Laurie Kellman, Associated Press Brian Friel, Bloomberg News RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Here Is the Original NPF Newsboy

AWARDS CEREMONY, 5:30 P.M. EST FOLLOWING THE AWARDS CEREMONY Sol Taishoff Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism: Audie Cornish, National Public Radio Panel discussion on the state of journalism today: George Will, Audie Cornish and Peter Bhatia with moderator Dana Bash of CNN. Presented by Adam Sharp, President and CEO of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Breakout sessions, 6:20 p.m.: Innovative Storytelling Award: Jonah Kessel and Hiroko Tabuchi, The New York Times · Minneapolis Star Tribune cartoonist Steve Sack, joined by last year’s Berryman winner, Presented by Heather Dahl, CEO, Indicio.tech RJ Matson. Honorable mention winner Ruben Bolling will join. PROGRAM TONIGHT’S Clifford K. & James T. Berryman Award for Editorial Cartoons: Steve Sack, Minneapolis Star Tribune · Time magazine’s Molly Ball, interviewed about her coverage of House Speaker Nancy Presented by Kevin Goldberg, Vice President, Legal, Digital Media Association Pelosi by Terence Samuel, managing editor of NPR. Honorable mention winner Chris Marquette of CQ Roll Call will speak about his work covering the Capitol Police. Benjamin C. Bradlee Editor of the Year Award: Peter Bhatia, Detroit Free Press · USA Today’s Brett Murphy and Letitia Stein will speak about the failures and future of Presented by Susan Swain, Co-President and CEO, C-SPAN the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, moderated by Elisabeth Rosenthal, editor- in-chief of Kaiser Health News. Everett McKinley Dirksen Award for Distinguished Reporting of Congress: Molly Ball, Time · The Washington Post’s David J. Lynch, Josh Dawsey, Jeff Stein and Carol Leonnig will Presented by Cissy Baker, Granddaughter of Senator Dirksen talk trade, moderated by Mark Hamrick of Bankrate.com. -

FALL 2002 Mason Laboratory, Room 211 Yale University, 9 Hillhouse Avenue (Next to St

BUSH CENTER IN CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIAL POLICY SOCIAL POLICY LUNCHEON SERIES – FALL 2002 Mason Laboratory, Room 211 Yale University, 9 Hillhouse Avenue (next to St. Mary’s Church), New Haven Web site: www.yale.edu/bushcenter/ 9/13 Edward Zigler Sterling Professor of Psychology and Director, Bush Center, Yale University Moving America to Universal Preschool Education 9/20 Dorothy S. Strickland Samuel DeWitt Proctor Professor in Education, Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Early Literacy Education: Problems, Pressures, and Promise 9/27 Janet S. Hansen Vice President and Director of Education Studies, Committee for Economic Development, Washington, DC Universal Preschool: An Idea Whose Time is Coming 10/4 Stanley J. Vitello Professor, Graduate School of Education, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Revitalizing or Revamping the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)? 10/11 Jim Greenman Senior Vice President, Bright Horizons Family Solutions, Minneapolis, MN Bright Horizons: The Drive for Quality, Innovation, and Responsibility to the Field and Community in a Public Child Care Company 10/18 Fred Rothbaum Professor, Eliot Pearson Department of Child Development and Nancy Martland Executive Director, Child & Family WebGuide, Tufts University, Medford, MA A Portal for Information About Children: The Child & Family WebGuide 10/25 Sari Horwitz and Scott Higham Metro Staff Writers, The Washington Post, and Winners of the 2002 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting, Washington, DC A Decade of Deadly Mistakes 11/1 Celia Fisher Professor of Applied Developmental Psychology and Director, Center for Ethics Education, Fordham University, Bronx, NY; Bioethicist in Residence 2002-2003, Yale University Ethics for Mental Health Science Involving Ethnic Minority Children and Youth 11/8 Richard J. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography Or Autobiography Year Winner 1917

A Monthly Newsletter of Ibadan Book Club – December Edition www.ibadanbookclub.webs.com, www.ibadanbookclub.wordpress.com E-mail:[email protected], [email protected] Pulitzer Prize Winners Biography or Autobiography Year Winner 1917 Julia Ward Howe, Laura E. Richards and Maude Howe Elliott assisted by Florence Howe Hall 1918 Benjamin Franklin, Self-Revealed, William Cabell Bruce 1919 The Education of Henry Adams, Henry Adams 1920 The Life of John Marshall, Albert J. Beveridge 1921 The Americanization of Edward Bok, Edward Bok 1922 A Daughter of the Middle Border, Hamlin Garland 1923 The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1924 From Immigrant to Inventor, Michael Idvorsky Pupin 1925 Barrett Wendell and His Letters, M.A. DeWolfe Howe 1926 The Life of Sir William Osler, Harvey Cushing 1927 Whitman, Emory Holloway 1928 The American Orchestra and Theodore Thomas, Charles Edward Russell 1929 The Training of an American: The Earlier Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Burton J. Hendrick 1930 The Raven, Marquis James 1931 Charles W. Eliot, Henry James 1932 Theodore Roosevelt, Henry F. Pringle 1933 Grover Cleveland, Allan Nevins 1934 John Hay, Tyler Dennett 1935 R.E. Lee, Douglas S. Freeman 1936 The Thought and Character of William James, Ralph Barton Perry 1937 Hamilton Fish, Allan Nevins 1938 Pedlar's Progress, Odell Shepard, Andrew Jackson, Marquis James 1939 Benjamin Franklin, Carl Van Doren 1940 Woodrow Wilson, Life and Letters, Vol. VII and VIII, Ray Stannard Baker 1941 Jonathan Edwards, Ola Elizabeth Winslow 1942 Crusader in Crinoline, Forrest Wilson 1943 Admiral of the Ocean Sea, Samuel Eliot Morison 1944 The American Leonardo: The Life of Samuel F.B.