Uib Doctor Thesis Content EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

N Ieman Reports

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 VOL. 62 NO. 1 SPRING 2008 21 ST CENTURY MUCKRAKERS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY 21st Century Muckrakers Who Are They? How Do They Do Their Work? Words & Reflections: Secrets, Sources and Silencing Watchdogs Journalism 2.0 End Note went to the Carnegie Endowment in New York but of the Oakland Tribune, and Maynard was throw- found times to return to Cambridge—like many, ing out questions fast and furiously about my civil I had “withdrawal symptoms” after my Harvard rights coverage. I realized my interview was lasting ‘to promote and elevate the year—and would meet with Tenney. She came to longer than most, and I wondered, “Is he trying to my wedding in Toronto in 1984, and we tried to knock me out of competition?” Then I happened to keep in touch regularly. Several of our class, Peggy glance over at Tenney and got the only smile from standards of journalism’ Simpson, Peggy Engel, Kat Harting, and Nancy the group—and a warm, welcoming one it was. I Day visited Tenney in her assisted living facility felt calmer. Finally, when the interview ended, I in Cambridge some years ago, during a Nieman am happy to say, Maynard leaped out of his chair reunion. She cared little about her own problems and hugged me. Agnes Wahl Nieman and was always interested in others. Curator Jim Tenney was a unique woman, and I thoroughly Thomson was the public and intellectual face of enjoyed her friendship. -

Theire Journal

CONTENTS 20 A MUCKRAKING LIFE THE IRE JOURNAL Early investigative journalist provides relevant lessons TABLE OF CONTENTS By Steve Weinberg MAY/JUNE 2003 The IRE Journal 4 IRE gaining momentum 22 – 31 FOLLOWING THE FAITHFUL in drive for “Breakthroughs” By Brant Houston PRIEST SCANDAL The IRE Journal Globe court battle unseals church records, 5 NEWS BRIEFS AND MEMBER NEWS reveals longtime abuse By Sacha Pfeiffer 8 WINNERS NAMED The Boston Globe IN 2002 IRE AWARDS By The IRE Journal FAITH HEALER Hidden cameras help, 12 2003 CONFERENCE LINEUP hidden records frustrate FEATURES HOTTEST TOPICS probe into televangelist By MaryJo Sylwester By Meade Jorgensen USA Today Dateline NBC 15 BUDGET PROPOSAL CITY PORTRAITS Despite economy, IRE stays stable, Role of religion increases training and membership starkly different By Brant Houston in town profiles The IRE Journal By Jill Lawrence USA Today COUNTING THE FAITHFUL 17 THE BLACK BELT WITH CHURCH ROLL DATA Alabama’s Third World IMAM UPROAR brought to public attention By Ron Nixon Imam’s history The IRE Journal By John Archibald, Carla Crowder hurts credibility and Jeff Hansen on local scene The Birmingham News By Tom Merriman WJW-Cleveland 18 INTERVIEWS WITH THE INTERVIEWERS Confrontational interviews By Lori Luechtefeld 34 TORTURE The IRE Journal Iraqi athletes report regime’s cruelties By Tom Farrey ESPN.com ABOUT THE COVER 35 FOI REPORT Bishop Wilton D. Gregory, Paper intervenes in case to argue for public database president of the U. S. Conference By Ziva Branstetter of Catholic Bishops, listens to a Tulsa World question after the opening session of the conference. -

![Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2843/illinois-municipalities-v-purdue-pharma-et-al-complaint-rff-932843.webp)

Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]

FILED 12-Person Jury 7/19/2018 7:00 AM DOROTHY BROWN CIRCUIT CLERK COOK COUNTY, IL 2018CH09020 IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CHANCERY DIVISION CITY OF HARVEY, VILLAGE OF BROADVIEW, Case No. 2018CH09020 VILLAGE OF CHICAGO RIDGE, VILLAGE OF DOLTON, VILLAGE OF HOFFMAN ESTATES, VILLAGE OF MAYWOOD, VILLAGE OF MERRIONETTE PARK, VILLAGE OF NORTH RIVERSIDE, VILLAGE OF ORLAND PARK, CITY OF PEORIA, VILLAGE OF POSEN, VILLAGE OF RIVER GROVE, VILLAGE OF STONE PARK, and ORLAND FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT, Plaintiffs, FILED DATE: 7/19/2018 7:00 AM 2018CH09020 v. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA, INC., PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., RHODES PHARMACEUTICALS, CEPHALON, INC., TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC, JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMACUETICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMAEUTICA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., NORMACO, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS, INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., ALLERGAN PLC, ACTAVIS PLC, WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, MALLINCKRODT PLC, MALLINCKRODT LLC, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., MCKESSON CORPORATION, PAUL MADISON, WILLIAM MCMAHON, and JOSEPH GIACCHINO, Defendants. COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs City of Harvey, Village of Broadview, Village of Chicago Ridge, Village of Dolton, Village of Hoffman Estates, Village of Maywood, Village of Merrionette Park, Village 1 of North Riverside, Village of Orland Park, City of Peoria, Village of Posen, Village of River Grove, Village of Stone Park, and Orland Fire Protection District bring this Complaint and Demand for Jury Trial to obtain redress in the form of monetary and injunctive relief from Defendants for their role in the opioid epidemic that has caused widespread harm and injuries to Plaintiffs’ communities. -

Views Expressed Are Those of the Cambridge Ma 02142

Cover_Sp2010 3/17/2010 11:30 AM Page 1 Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: the challenges of Bruce Western, Glenn Loury, Lawrence D. Bobo, Marie Gottschalk, Dædalus mass incarceration Jonathan Simon, Robert J. Sampson, Robert Weisberg, Joan Petersilia, Nicola Lacey, Candace Kruttschnitt, Loïc Wacquant, Mark Kleiman, Jeffrey Fagan, and others Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2010 the economy Robert M. Solow, Benjamin M. Friedman, Lucian A. Bebchuk, Luigi Zingales, Edward Glaeser, Charles Goodhart, Barry Eichengreen, of news Spring 2010: on the future Thomas Romer, Peter Temin, Jeremy Stein, Robert E. Hall, and others on the Loren Ghiglione Introduction 5 future Herbert J. Gans News & the news media in the digital age: the meaning of Gerald Early, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Glenda R. Carpio, David A. of news implications for democracy 8 minority/majority Hollinger, Jeffrey B. Ferguson, Hua Hsu, Daniel Geary, Lawrence Kathleen Hall Jamieson Are there lessons for the future of news from Jackson, Farah Grif½n, Korina Jocson, Eric Sundquist, Waldo Martin, & Jeffrey A. Gottfried the 2008 presidential campaign? 18 Werner Sollors, James Alan McPherson, Robert O’Meally, Jeffrey B. Robert H. Giles New economic models for U.S. journalism 26 Perry, Clarence Walker, Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Tommie Shelby, and others Jill Abramson Sustaining quality journalism 39 Brant Houston The future of investigative journalism 45 Donald Kennedy The future of science news 57 race, inequality Lawrence D. Bobo, William Julius Wilson, Michael Klarman, Rogers Ethan Zuckerman International reporting in the age of & culture Smith, Douglas Massey, Jennifer Hochschild, Bruce Western, Martha participatory media 66 Biondi, Roland Fryer, Cathy Cohen, James Heckman, Taeku Lee, Pap Ndiaye, Marcyliena Morgan, Richard Nisbett, Jennifer Richeson, Mitchell Stephens The case for wisdom journalism–and for journalists surrendering the pursuit Daniel Sabbagh, Alford Young, Roger Waldinger, and others of news 76 Jane B. -

1:17-Md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. Pageid #: 13544

Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. PageID #: 13544 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION IN RE NATIONAL PRESCRIPTION MDL No. 2804 OPIATE LITIGATION Case No. 17-md-2804 This document relates to: Judge Dan Aaron Polster Case No. 18-OP-45332 (N.D. Ohio) BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA, SECOND AMENDED COMPLAINT (REDACTED) Plaintiff, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL vs. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA INC., THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICA, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., NORAMCO, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL- JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., CEPHALON, INC., ALLERGAN PLC f/k/a ACTAVIS PLC, ALLERGAN FINANCE LLC, f/k/a ACTAVIS, INC., f/k/a WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC. f/k/a WATSON PHARMA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., MALLINCKRODT PLC, 1545690.37 Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 2 of 315. PageID #: 13545 MALLINCKRODT LLC, SPECGX LLC, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., McKESSON CORPORATION, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, HEALTH MART SYSTEMS, INC., H. D. SMITH, LLC d/b/a HD SMITH, f/k/a H.D. SMITH WHOLESALE DRUG CO., H. D. SMITH HOLDINGS, LLC, H. D. SMITH HOLDING COMPANY, CVS HEALTH CORPORATION, WALGREENS BOOTS ALLIANCE, INC. a/k/a WALGREEN CO., and WAL-MART INC. f/k/a WAL-MART STORES, INC., Defendants. -

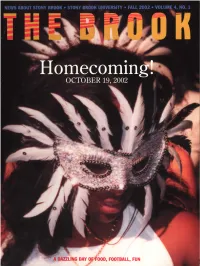

Thebrook Fall02.Pdf

DAY O'OOD, FOOTBALL, FUN nte I)sk of Jane Knap CONTEINTS To all my fellow Stony Brook alumni, I'm delighted to What's New On Campus 3 greet you as incoming president of the Stony Brook Ambulatory Surgery Center Opens; Asian Fall Festival at Stony Brook Alumni Association. Thanks to outgoing president Mark Snyder, I'm taking the reins of a dynamic organization Research Roundup 4 Geometry as a spy tool? Modern art on the with a real sense of purpose and ambition. Web-a new interactive medium. How a This is an exciting time to be a Stony Brook alum. Evidence turkey is helping Stony Brook researchers combat osteoporosis of a surging University is all around us. From front-page New York Times coverage of Professor Eckard Wimmer's synthesis of Extra! Extra! 6 the polio virus to Shirley Strum Kenny's ongoing transformation Former Stony Brook Press editor wins journalism's most coveted prize-the Pulitzer of the campus, Stony Brook is happening. Even the new and expanded Brook you're reading demonstrates that Stony Brook Catch Our Rising Stars 8 Meet is a class act. Stony Brook's student ambassadors- as they ascend the academic heights For alumni who haven't been back to campus in years, it's difficult to capture in words the spirit of Stony Brook today. Past and Present 10 A conversation with former University Even for those of us who come from an era when Stony Brook President John S. Toll and President Kenny was more grime than grass, today our alma mater is a source of tremendous pride--one of the nation's elite universities. -

Law As Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Law as Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism Roy Shapir Legal scholarshave long recognized that the media plays a key role in assuring the proper functioning of political and business markets Yet we have understudied the role of law in assuring effective media scrutiny. This Article develops a theory of law as source. The basicpremise is that the law not only regulates what the media can or cannot say, but also facilitates media scrutiny by producing information. Specifically, law enforcement actions, such as litigationor regulatory investigations, extract information on the behaviorofpowerfulplayers in business or government. Journalists can then translate the information into biting investigative reports and diffuse them widely, thereby shapingplayers' reputationsand norms. Levels of accountabilityin society are therefore not simply a function of the effectiveness of the courts as a watchdog or the media as a watchdog but rather a function of the interactions between the two watchdogs. This Article approaches, from multiple angles, the questions of how and how much the media relies on legal sources. I analyze the content of projects that won investigative reportingprizes in the past two decades; interview forty veteran reporters; scour a reporters-onlydatabase of tip sheets and how-to manuals; go over * IDC Law School. I thank participants in the Information in Litigation Roundtable at Washington & Lee, the Annual Corporate and Securities Litigation Workshop at UCLA, several conferences at IDC, the American Law and Economics Association annual conference at Boston University, and the Crisis in the Theory of the Firm conference and the Annual Reputation Symposium at Oxford University, as well as Jonathan Glater, James Hamilton, Andrew Tuch, and Verity Winship for helpful comments and discussions. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournalmayjun2004; Thu Apr 1

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 20 - 29 TRACKING SEX OFFENDERS TABLE OF CONTENTS MAY/JUNE 2004 OFFENDER SCREENING Likely predators released 4 Media insurers may push despite red-flag testing strong journalism training By John Stefany to manage risks, costs (Minnneapolis) Star Tribune By Brant Houston The IRE Journal STATE REGISTRY System fails to keep tabs 10 Top investigative work on released sex offenders named in 2003 IRE Awards By Frank Gluck By The IRE Journal The (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) Gazette 14 2004 IRE Conference to feature best in business COACHING THREAT By The IRE Journal Abuse of female athletes often covered up, ignored 16 BUDGET PROPOSAL By Christine Willmsen Organization maintains steady, conservative The Seattle Times course in light of tight training, data budgets in newsrooms By Brant Houston The IRE Journal 30 IMMIGRANT PROFILING 18 PUBLIC RECORDS Arabs face scrutiny in Detroit area Florida fails access test in joint newspaper audit in two years following 9/11 terrorist attacks By John Bebow By Chris Davis and Matthew Doig for The IRE Journal Sarasota Herald-Tribune 19 FOI REPORT 32 Irreverent approach to freelancing Privacy exemptions explains the need to break the rules may prove higher hurdle By Steve Weinberg than national security The IRE Journal By Jennifer LaFleur Checking criminal backgrounds The Dallas Morning News 33 By Carolyn Edds The IRE Journal ABOUT THE COVER 34 UNAUDITED STATE SPENDING Law enforcement has a tough Yes, writing about state budgets can sometimes be fun time keeping track of sexual By John M.R. Bull predators – often until they The (Allentown, Pa.) Morning Call re-offend and find themselves 35 LEGAL CORNER back in custody. -

Justice Heartland

13TH ANNUAL HARRY FRANK GUGGENHEIM SYMPOSIUM ON CRIME IN AMERICA JUSTICE IN THE HEARTLAND FEBRUARY 15TH AND 16TH, 2018 JOHN JAY COLLEGE 524 W. 59TH STREET NEW YORK, NY AGENDA THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 15 All Thursday panels take place in the Moot Court, John Jay College, 6th Floor of the new building 8:30 – 9:00am CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 12:30 – 2:30pm LUNCH for Fellows and invited guests only 9:00 – 9:30am WELCOME THE WHITE HOUSE PRISON Stephen Handelman, Director, Center on Media REFORM INITIATIVES Crime and Justice, John Jay College Mark Holden, Senior VP and General Counsel, Daniel F. Wilhelm, President, Harry Frank Koch Industries Guggenheim Foundation 2:30 – 4:00pm Karol V. Mason, President, John Jay College PANEL 3: of Criminal Justice CRIME TRENDS 2017-2018— 9:30 – 11:00am IS THE HOMICIDE ‘SPIKE’ REAL? PANEL 1: OPIATES— Thomas P. Abt, Senior Fellow, Harvard Law School AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY (PART 1) Alfred Blumstein, J. Erik Jonsson University Professor of Urban Systems and Operations Research, José Diaz-Briseño, Washington correspondent, Carnegie Mellon University La Reforma, Mexico Shytierra Gaston, Assistant Professor, Department Paul Cell, First Vice President, International of Criminal Justice, Indiana University-Bloomington Association of Chiefs of Police; Chief of Police, Montclair State University (NJ) Richard Rosenfeld, Founders Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University Rita Noonan, Chief, Health Systems and Trauma of Missouri - St. Louis Systems Branch, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MODERATOR Cheri Walter, Chief Executive Officer, The Ohio Robert Jordan Jr, former anchor, Chicago WGN-TV Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities MODERATOR 4:00 – 4:15pm BREAK Kevin Johnson, journalist, USA Today 4:15 – 6:00pm 11:00am – 12:30pm PANEL 4: CORRECTIONS / PANEL 2: OPIATES— SENTENCING REFORM UPDATE THE BATTLE SO FAR (PART 2) Leann Bertsch, President, Association of State Correctional Administrators; Director, North Dakota The Hon. -

Press Galleries* Rules Governing Press

PRESS GALLERIES* SENATE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–316, phone 224–0241 Director.—S. Joseph Keenan Deputy Director.—Joan McKinney Media Coordinators: Michael Cavaiola Wendy A. Oscarson Amy H. Gross James D. Saris HOUSE PRESS GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–315, phone 225–3945 Superintendent.—Jerry L. Gallegos Deputy Superintendent.—Justin J. Supon Assistant Superintendents: Ric Andersen Drew Cannon Molly Cain Laura Reed STANDING COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENTS Bill Walsh, Times-Picayne, Chair Thomas Ferraro, Reuters, Secretary Susan Ferrechio, Congressional Quarterly Carl Hulse, New York Times Andrew Taylor, Associated Press RULES GOVERNING PRESS GALLERIES 1. Administration of the press galleries shall be vested in a Standing Committee of Cor- respondents elected by accredited members of the galleries. The Committee shall consist of five persons elected to serve for terms of two years. Provided, however, that at the election in January 1951, the three candidates receiving the highest number of votes shall serve for two years and the remaining two for one year. Thereafter, three members shall be elected in odd-numbered years and two in even-numbered years. Elections shall be held in January. The Committee shall elect its own chairman and secretary. Vacancies on the Committee shall be filled by special election to be called by the Standing Committee. 2. Persons desiring admission to the press galleries of Congress shall make application in accordance with Rule VI of the House of Representatives, subject to the direction and control of the Speaker and Rule 33 of the Senate, which rules shall be interpreted and administered by the Standing Committee of Correspondents, subject to the review and an approval by the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration. -

Hammer V. Ashcroft

No. 09-504 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _________________________ DAVID PAUL HAMMER, PETITIONER, v. JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ET AL. _________________________ ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT _________________________ BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND TWENTY-THREE NEWS MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _________________________ Lucy A. Dalglish Counsel of Record Gregg P. Leslie John Rory Eastburg The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, Va. 22209 (703) 807-2100 (Additional counsel for amici listed in Appendix B.) i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Authorities .................................................... ii Statement of Interest.................................................. 1 Summary of Argument ............................................... 3 Argument .................................................................... 5 I. The decision below imperils valuable communication between inmates and the press .. 5 A. Inmate interviews expose abuse and spur prison reform.................................................... 6 B. Inmate interviews provide unique insight into prison conditions .......................... 8 C. Inmate interviews help citizens monitor how their tax dollars are spent...................... 10 II. The court below erred in approving a policy that allows no method of uncensored communication with the press............................ 12 A. Previous