Fort Lauderdale Complaint (Clean with SJW Edits As of 10/29/18 at 4Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2843/illinois-municipalities-v-purdue-pharma-et-al-complaint-rff-932843.webp)

Illinois Municipalities V. Purdue Pharma Et Al – Complaint [RFF]

FILED 12-Person Jury 7/19/2018 7:00 AM DOROTHY BROWN CIRCUIT CLERK COOK COUNTY, IL 2018CH09020 IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF COOK COUNTY, ILLINOIS COUNTY DEPARTMENT, CHANCERY DIVISION CITY OF HARVEY, VILLAGE OF BROADVIEW, Case No. 2018CH09020 VILLAGE OF CHICAGO RIDGE, VILLAGE OF DOLTON, VILLAGE OF HOFFMAN ESTATES, VILLAGE OF MAYWOOD, VILLAGE OF MERRIONETTE PARK, VILLAGE OF NORTH RIVERSIDE, VILLAGE OF ORLAND PARK, CITY OF PEORIA, VILLAGE OF POSEN, VILLAGE OF RIVER GROVE, VILLAGE OF STONE PARK, and ORLAND FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT, Plaintiffs, FILED DATE: 7/19/2018 7:00 AM 2018CH09020 v. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA, INC., PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., RHODES PHARMACEUTICALS, CEPHALON, INC., TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES, LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., ENDO INTERNATIONAL PLC, JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL-JANSSEN PHARMACUETICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMAEUTICA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., NORMACO, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS, INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., ALLERGAN PLC, ACTAVIS PLC, WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, MALLINCKRODT PLC, MALLINCKRODT LLC, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., MCKESSON CORPORATION, PAUL MADISON, WILLIAM MCMAHON, and JOSEPH GIACCHINO, Defendants. COMPLAINT AND DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Plaintiffs City of Harvey, Village of Broadview, Village of Chicago Ridge, Village of Dolton, Village of Hoffman Estates, Village of Maywood, Village of Merrionette Park, Village 1 of North Riverside, Village of Orland Park, City of Peoria, Village of Posen, Village of River Grove, Village of Stone Park, and Orland Fire Protection District bring this Complaint and Demand for Jury Trial to obtain redress in the form of monetary and injunctive relief from Defendants for their role in the opioid epidemic that has caused widespread harm and injuries to Plaintiffs’ communities. -

Pain Management & Palliative Care

Guidelines on Pain Management & Palliative Care A. Paez Borda (chair), F. Charnay-Sonnek, V. Fonteyne, E.G. Papaioannou © European Association of Urology 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Guideline 6 1.2 Methodology 6 1.3 Publication history 6 1.4 Acknowledgements 6 1.5 Level of evidence and grade of guideline recommendations* 6 1.6 References 7 2. BACKGROUND 7 2.1 Definition of pain 7 2.2 Pain evaluation and measurement 7 2.2.1 Pain evaluation 7 2.2.2 Assessing pain intensity and quality of life (QoL) 8 2.3 References 9 3. CANCER PAIN MANAGEMENT (GENERAL) 10 3.1 Classification of cancer pain 10 3.2 General principles of cancer pain management 10 3.3 Non-pharmacological therapies 11 3.3.1 Surgery 11 3.3.2 Radionuclides 11 3.3.2.1 Clinical background 11 3.3.2.2 Radiopharmaceuticals 11 3.3.3 Radiotherapy for metastatic bone pain 13 3.3.3.1 Clinical background 13 3.3.3.2 Radiotherapy scheme 13 3.3.3.3 Spinal cord compression 13 3.3.3.4 Pathological fractures 14 3.3.3.5 Side effects 14 3.3.4 Psychological and adjunctive therapy 14 3.3.4.1 Psychological therapies 14 3.3.4.2 Adjunctive therapy 14 3.4 Pharmacotherapy 15 3.4.1 Chemotherapy 15 3.4.2 Bisphosphonates 15 3.4.2.1 Mechanisms of action 15 3.4.2.2 Effects and side effects 15 3.4.3 Denosumab 16 3.4.4 Systemic analgesic pharmacotherapy - the analgesic ladder 16 3.4.4.1 Non-opioid analgesics 17 3.4.4.2 Opioid analgesics 17 3.4.5 Treatment of neuropathic pain 21 3.4.5.1 Antidepressants 21 3.4.5.2 Anticonvulsant medication 21 3.4.5.3 Local analgesics 22 3.4.5.4 NMDA receptor antagonists 22 3.4.5.5 Other drug treatments 23 3.4.5.6 Invasive analgesic techniques 23 3.4.6 Breakthrough cancer pain 24 3.5 Quality of life (QoL) 25 3.6 Conclusions 26 3.7 References 26 4. -

A Matter of Record (301) 890-4188 FOOD and DRUG

1 1 FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION 2 CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH 3 4 5 JOINT MEETING OF THE ANESTHETIC AND ANALGESIC 6 DRUG PRODUCTS ADVISORY COMMITTEE (AADPAC) 7 AND THE DRUG SAFETY AND RISK MANAGEMENT 8 ADVISORY COMMITTEE (DSaRM) AND THE 9 PEDIATRIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE (PAC) 10 11 Friday, September 16, 2016 12 8:07 a.m. to 2:39 p.m. 13 14 15 FDA White Oak Campus 16 10903 New Hampshire Avenue 17 Building 31 Conference Center 18 The Great Room (Rm. 1503) 19 Silver Spring, Maryland 20 21 22 A Matter of Record (301) 890-4188 2 1 Meeting Roster 2 DESIGNATED FEDERAL OFFICER (Non-Voting) 3 Stephanie L. Begansky, PharmD 4 Division of Advisory Committee and Consultant 5 Management 6 Office of Executive Programs, CDER, FDA 7 8 ANESTHETIC AND ANALGESIC DRUG PRODUCTS ADVISORY 9 COMMITTEE MEMBERS (Voting) 10 Brian T. Bateman, MD, MSc 11 Associate Professor of Anesthesia 12 Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and 13 Pharmacoeconomics 14 Department of Medicine 15 Brigham and Women’s Hospital 16 Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain 17 Medicine 18 Massachusetts General Hospital 19 Harvard Medical School 20 Boston, Massachusetts 21 22 A Matter of Record (301) 890-4188 3 1 Raeford E. Brown, Jr., MD, FAAP 2 (Chairperson) 3 Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics 4 College of Medicine 5 University of Kentucky 6 Lexington, Kentucky 7 8 David S. Craig, PharmD 9 Clinical Pharmacy Specialist 10 Department of Pharmacy 11 H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute 12 Tampa, Florida 13 14 Charles W. Emala, Sr., MS, MD 15 Professor and Vice-Chair for Research 16 Department of Anesthesiology 17 Columbia University College of Physicians & 18 Surgeons 19 New York, New York 20 21 22 A Matter of Record (301) 890-4188 4 1 Anita Gupta, DO, PharmD 2 (via telephone on day 1) 3 Vice Chair and Associate Professor 4 Division of Pain Medicine & Regional 5 Anesthesiology 6 Department of Anesthesiology 7 Drexel University College of Medicine 8 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 9 10 Jennifer G. -

1:17-Md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. Pageid #: 13544

Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 1 of 315. PageID #: 13544 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION IN RE NATIONAL PRESCRIPTION MDL No. 2804 OPIATE LITIGATION Case No. 17-md-2804 This document relates to: Judge Dan Aaron Polster Case No. 18-OP-45332 (N.D. Ohio) BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA, SECOND AMENDED COMPLAINT (REDACTED) Plaintiff, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL vs. PURDUE PHARMA L.P., PURDUE PHARMA INC., THE PURDUE FREDERICK COMPANY, INC., ENDO HEALTH SOLUTIONS INC., ENDO PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL, INC., PAR PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICA, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., NORAMCO, INC., ORTHO-MCNEIL- JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. n/k/a JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., JOHNSON & JOHNSON, TEVA PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LTD., TEVA PHARMACEUTICALS USA, INC., CEPHALON, INC., ALLERGAN PLC f/k/a ACTAVIS PLC, ALLERGAN FINANCE LLC, f/k/a ACTAVIS, INC., f/k/a WATSON PHARMACEUTICALS, INC., WATSON LABORATORIES, INC., ACTAVIS LLC, ACTAVIS PHARMA, INC. f/k/a WATSON PHARMA, INC., INSYS THERAPEUTICS, INC., MALLINCKRODT PLC, 1545690.37 Case: 1:17-md-02804-DAP Doc #: 525 Filed: 05/30/18 2 of 315. PageID #: 13545 MALLINCKRODT LLC, SPECGX LLC, CARDINAL HEALTH, INC., McKESSON CORPORATION, AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORPORATION, HEALTH MART SYSTEMS, INC., H. D. SMITH, LLC d/b/a HD SMITH, f/k/a H.D. SMITH WHOLESALE DRUG CO., H. D. SMITH HOLDINGS, LLC, H. D. SMITH HOLDING COMPANY, CVS HEALTH CORPORATION, WALGREENS BOOTS ALLIANCE, INC. a/k/a WALGREEN CO., and WAL-MART INC. f/k/a WAL-MART STORES, INC., Defendants. -

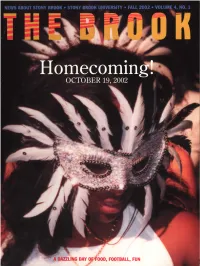

Thebrook Fall02.Pdf

DAY O'OOD, FOOTBALL, FUN nte I)sk of Jane Knap CONTEINTS To all my fellow Stony Brook alumni, I'm delighted to What's New On Campus 3 greet you as incoming president of the Stony Brook Ambulatory Surgery Center Opens; Asian Fall Festival at Stony Brook Alumni Association. Thanks to outgoing president Mark Snyder, I'm taking the reins of a dynamic organization Research Roundup 4 Geometry as a spy tool? Modern art on the with a real sense of purpose and ambition. Web-a new interactive medium. How a This is an exciting time to be a Stony Brook alum. Evidence turkey is helping Stony Brook researchers combat osteoporosis of a surging University is all around us. From front-page New York Times coverage of Professor Eckard Wimmer's synthesis of Extra! Extra! 6 the polio virus to Shirley Strum Kenny's ongoing transformation Former Stony Brook Press editor wins journalism's most coveted prize-the Pulitzer of the campus, Stony Brook is happening. Even the new and expanded Brook you're reading demonstrates that Stony Brook Catch Our Rising Stars 8 Meet is a class act. Stony Brook's student ambassadors- as they ascend the academic heights For alumni who haven't been back to campus in years, it's difficult to capture in words the spirit of Stony Brook today. Past and Present 10 A conversation with former University Even for those of us who come from an era when Stony Brook President John S. Toll and President Kenny was more grime than grass, today our alma mater is a source of tremendous pride--one of the nation's elite universities. -

Law As Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Law as Source: How the Legal System Facilitates Investigative Journalism Roy Shapir Legal scholarshave long recognized that the media plays a key role in assuring the proper functioning of political and business markets Yet we have understudied the role of law in assuring effective media scrutiny. This Article develops a theory of law as source. The basicpremise is that the law not only regulates what the media can or cannot say, but also facilitates media scrutiny by producing information. Specifically, law enforcement actions, such as litigationor regulatory investigations, extract information on the behaviorofpowerfulplayers in business or government. Journalists can then translate the information into biting investigative reports and diffuse them widely, thereby shapingplayers' reputationsand norms. Levels of accountabilityin society are therefore not simply a function of the effectiveness of the courts as a watchdog or the media as a watchdog but rather a function of the interactions between the two watchdogs. This Article approaches, from multiple angles, the questions of how and how much the media relies on legal sources. I analyze the content of projects that won investigative reportingprizes in the past two decades; interview forty veteran reporters; scour a reporters-onlydatabase of tip sheets and how-to manuals; go over * IDC Law School. I thank participants in the Information in Litigation Roundtable at Washington & Lee, the Annual Corporate and Securities Litigation Workshop at UCLA, several conferences at IDC, the American Law and Economics Association annual conference at Boston University, and the Crisis in the Theory of the Firm conference and the Annual Reputation Symposium at Oxford University, as well as Jonathan Glater, James Hamilton, Andrew Tuch, and Verity Winship for helpful comments and discussions. -

Pain: the Fifth Vital Sign.” 17

1 In 2001, as part of a national effort to address the widespread problem of underassessment and undertreatment of pain, The Joint Commission (formerly The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations or JCAHO) introduced standards for organizations to improve their care for patients with pain.1 For over a decade, experts had called for better assessment and more aggressive treatment, including the use of opioids.2 Many doctors were afraid to prescribe opioids despite a widely cited article suggesting that addiction was rare when opioids were used for short-term pain.3 Education, guidelines, and advocacy had not changed practice, and leaders called for stronger methods to address the problem.4-7 The standards were based on the available evidence and the strong consensus opinions of experts in the field. After initial accolades and small studies showing the benefits of following the standards, reports began to emerge about adverse events from overly aggressive treatment, particularly respiratory depression after receiving opioids. A report from The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) asked, “Has safety been compromised in our noble efforts to alleviate pain?”8 In response to these unintended consequences, the standards and related materials were quickly changed to address some of the problems that had arisen. But lingering criticisms of the standards continue to this day, often based on misperceptions of what the current standards actually say. This article reviews the history of The Joint Commission standards, the changes that were made over time to try to maintain the positive effects they had on pain assessment and management while mitigating the unintended consequences, and recent efforts to update the standards and add new standards to address today’s opioid epidemic in the United States. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournalmayjun2004; Thu Apr 1

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 20 - 29 TRACKING SEX OFFENDERS TABLE OF CONTENTS MAY/JUNE 2004 OFFENDER SCREENING Likely predators released 4 Media insurers may push despite red-flag testing strong journalism training By John Stefany to manage risks, costs (Minnneapolis) Star Tribune By Brant Houston The IRE Journal STATE REGISTRY System fails to keep tabs 10 Top investigative work on released sex offenders named in 2003 IRE Awards By Frank Gluck By The IRE Journal The (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) Gazette 14 2004 IRE Conference to feature best in business COACHING THREAT By The IRE Journal Abuse of female athletes often covered up, ignored 16 BUDGET PROPOSAL By Christine Willmsen Organization maintains steady, conservative The Seattle Times course in light of tight training, data budgets in newsrooms By Brant Houston The IRE Journal 30 IMMIGRANT PROFILING 18 PUBLIC RECORDS Arabs face scrutiny in Detroit area Florida fails access test in joint newspaper audit in two years following 9/11 terrorist attacks By John Bebow By Chris Davis and Matthew Doig for The IRE Journal Sarasota Herald-Tribune 19 FOI REPORT 32 Irreverent approach to freelancing Privacy exemptions explains the need to break the rules may prove higher hurdle By Steve Weinberg than national security The IRE Journal By Jennifer LaFleur Checking criminal backgrounds The Dallas Morning News 33 By Carolyn Edds The IRE Journal ABOUT THE COVER 34 UNAUDITED STATE SPENDING Law enforcement has a tough Yes, writing about state budgets can sometimes be fun time keeping track of sexual By John M.R. Bull predators – often until they The (Allentown, Pa.) Morning Call re-offend and find themselves 35 LEGAL CORNER back in custody. -

IAC Ch 13, P.1 653—13.2(148,272C) Standards of Practice—Appropriate

IAC Ch 13, p.1 653—13.2(148,272C) Standards of practice—appropriate pain management. This rule establishes standards of practice for the management of acute and chronic pain. The board encourages the use of adjunct therapies such as acupuncture, physical therapy and massage in the treatment of acute and chronic pain. This rule focuses on prescribing and administering controlled substances to provide relief and eliminate suffering for patients with acute or chronic pain. 1. This rule is intended to encourage appropriate pain management, including the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain, while stressing the need to establish safeguards to minimize the potential for substance abuse and drug diversion. 2. The goal of pain management is to treat each patient’s pain in relation to the patient’s overall health, including physical function and psychological, social and work-related factors. At the end of life, the goals may shift to palliative care. 3. The board recognizes that pain management, including the use of controlled substances, is an important part of general medical practice. Unmanaged or inappropriately treated pain impacts patients’ quality of life, reduces patients’ ability to be productive members of society, and increases patients’ use of health care services. 4. Physicians should not fear board action for treating pain with controlled substances as long as the physicians’ prescribing is consistent with appropriate pain management practices. Dosage alone is not the sole measure of determining whether a physician has complied with appropriate pain management practices. The board recognizes the complexity of treating patients with chronic pain or a substance abuse history. -

Justice Heartland

13TH ANNUAL HARRY FRANK GUGGENHEIM SYMPOSIUM ON CRIME IN AMERICA JUSTICE IN THE HEARTLAND FEBRUARY 15TH AND 16TH, 2018 JOHN JAY COLLEGE 524 W. 59TH STREET NEW YORK, NY AGENDA THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 15 All Thursday panels take place in the Moot Court, John Jay College, 6th Floor of the new building 8:30 – 9:00am CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST 12:30 – 2:30pm LUNCH for Fellows and invited guests only 9:00 – 9:30am WELCOME THE WHITE HOUSE PRISON Stephen Handelman, Director, Center on Media REFORM INITIATIVES Crime and Justice, John Jay College Mark Holden, Senior VP and General Counsel, Daniel F. Wilhelm, President, Harry Frank Koch Industries Guggenheim Foundation 2:30 – 4:00pm Karol V. Mason, President, John Jay College PANEL 3: of Criminal Justice CRIME TRENDS 2017-2018— 9:30 – 11:00am IS THE HOMICIDE ‘SPIKE’ REAL? PANEL 1: OPIATES— Thomas P. Abt, Senior Fellow, Harvard Law School AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY (PART 1) Alfred Blumstein, J. Erik Jonsson University Professor of Urban Systems and Operations Research, José Diaz-Briseño, Washington correspondent, Carnegie Mellon University La Reforma, Mexico Shytierra Gaston, Assistant Professor, Department Paul Cell, First Vice President, International of Criminal Justice, Indiana University-Bloomington Association of Chiefs of Police; Chief of Police, Montclair State University (NJ) Richard Rosenfeld, Founders Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University Rita Noonan, Chief, Health Systems and Trauma of Missouri - St. Louis Systems Branch, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MODERATOR Cheri Walter, Chief Executive Officer, The Ohio Robert Jordan Jr, former anchor, Chicago WGN-TV Association of County Behavioral Health Authorities MODERATOR 4:00 – 4:15pm BREAK Kevin Johnson, journalist, USA Today 4:15 – 6:00pm 11:00am – 12:30pm PANEL 4: CORRECTIONS / PANEL 2: OPIATES— SENTENCING REFORM UPDATE THE BATTLE SO FAR (PART 2) Leann Bertsch, President, Association of State Correctional Administrators; Director, North Dakota The Hon. -

Nurses' Attitudes and Practices in Sickle Cell Pain Management

Nurses’ Attitudes and Practices in Sickle Cell Pain Management Ardie Pack-Mabien, E. Labbe, D. Herbert, and J. Haynes, Jr. Professional objectivity should be the primary focus of patient care. Health care professionals are at times reluctant to give opioids out of fear that patients may become addicted, which would result in the undertreatment of pain. The influence of nurses’ attitudes on the management of sickle cell pain was studied. The variables of age, education, area of practice, and years of active experience were considered. Of the respondents, 63% believed addiction was prevalent, and 30% were hesitant to administer high-dose opioids. Study findings suggest that nurses would benefit from additional education on sickle cell disease, pain assessment and management, and addiction. Educational recommendations are discussed. Copyright © 2001 by W.B. Saunders Company ICKLE CELL DISEASE (SCD) is a chronic he- the patient, family, community, and health care S matological disorder that is characterized by the professionals (Shapiro, Benjamin, Payne, & Heid- production of hemoglobin S in the erythrocyte, vaso- rich, 1997). It is important to understand that an occlusion, and hemolytic anemia. Hemoglobin S dif- individual’s perception and appreciation of pain fers from normal hemoglobin A by a single amino acid are complex phenomena influenced by numerous substitution of valine for glutamic acid at the number 6 variables such as coping mechanisms, chronicity, position of the beta chain on chromosome 11. Chronic accessibility to health care, support structure, cul- hemolytic anemia, recurrent vaso-occlusive pain epi- ture, age, and gender. sodes, acute and chronic organ damage, and increased Additionally, an individual’s perception of pain susceptibility to infection characterize SCD. -

Pain: Current Understanding of Assessment, Management, and Treatments

Pain: Current Understanding of Assessment, Management, and Treatments NATIONAL PHARMACEUTICAL COUNCIL, INC This monograph was developed by NPC as part of a collaborative project with JCAHO. December 2001 DISCLAIMER: This monograph was developed by the National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC) for which it is solely responsible. Another monograph relat- ed to measuring and improving performance in pain management was developed by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) for which it is solely responsible. The two monographs were produced under a collaborative project between NPC and JCAHO and are jointly dis- tributed. The goal of the collaborative project is to improve the quality of pain management in health care organizations. This monograph is designed for informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for medical or professional advice. Readers are urged to consult a qualified health care professional before making decisions on any specific matter, particularly if it involves clinical practice. The inclusion of any reference in this monograph should not be construed as an endorsement of any of the treatments, programs or other information discussed therein. NPC has worked to ensure that this monograph contains useful information, but this monograph is not intended as a comprehensive source of all relevant information. In addi- tion, because the information contain herein is derived from many sources, NPC cannot guarantee that the information is completely accurate or error free. NPC is not responsible for any claims or losses arising from the use of, or from any errors or omissions in, this monograph. Editorial Advisory Board Patricia H. Berry, PhD, APRN, BC, CHPN Jeffrey A.